China Terrain

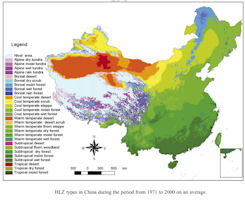

Terrain and vegetation vary greatly in China. Remarkably varied landscapes suggest the disparate climate and broad reach of China, the third largest country in the world in terms of area. China's climate ranges from subarctic to tropical. Its topography includes the world's highest peaks, tortuous but picturesque river valleys, and vast plains subject to life threatening but soil-enriching flooding. These characteristics have dictated where the Chinese people live and how they make their livelihood.

Terrain and vegetation vary greatly in China. Remarkably varied landscapes suggest the disparate climate and broad reach of China, the third largest country in the world in terms of area. China's climate ranges from subarctic to tropical. Its topography includes the world's highest peaks, tortuous but picturesque river valleys, and vast plains subject to life threatening but soil-enriching flooding. These characteristics have dictated where the Chinese people live and how they make their livelihood.

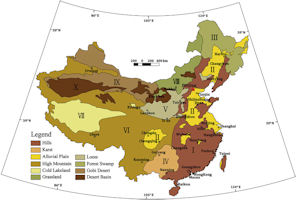

From the standpoint of topography, China is divided into four sections: a, the northern uplands, including Mongolia, Shansi, Hopeh, and part of Manchuria; b, the central plain, or the area running roughly southeast from Peking to Shanghai and up the Yangtze to the head of deep-water navigation at I-ch'ang; c, the Central Mountain Belt in the northwest, central west, roughly separating north China from South China; d, and the high lands of the southern coast of Yunnan, and of western Szechwan. This breakdown does not, of course, in view of China's size), give areas that are topographically homogeneous, and it includes mainly the part of China on the mainland and south, of the Great Wall, i.e., "China Proper."

China's topography was completely formed around the emergence of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, the most important geological event over the past several million years. Taking a bird's-eye view of China, the terrain gradually descends from west to east like a staircase. Due to the collision of the Indian and Eurasian plates, the young Qinghai-Tibet Plateau rose continuously to become the top of the four-step "staircase," averaging more than 4,000 m above sea level, and called "the roof of the world." Soaring 8,850 m above sea level on the plateau is Mt. Qomolangma, the world's highest peak and the main peak of the Himalayas. The second step includes the gently sloping Inner Mongolia Plateau, the Loess Plateau, the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau, the Tarim Basin, the Junggar Basin and the Sichuan Basin, with an average elevation of between 1,000 m and 2,000 m.

The third step, dropping to 500-1,000 m in elevation, begins at a line drawn around the Greater Hinggan, Taihang, Wushan and Xuefeng mountain ranges and extends eastward to the coast of the Pacific Ocean. Here, from north to south, are the Northeast Plain, the North China Plain and the Middle-Lower Yangtze Plain. Interspersed amongst the plains are hills and foothills. To the east, the land extends out into the ocean, in a continental shelf, the fourth step of the staircase. The water here is less than 200 m deep. The area of mountains and hills and plateaus account for 65 percent of the total land area of China.

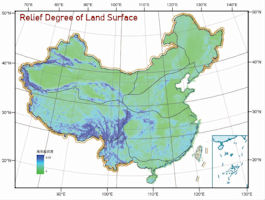

The relief degree of land surface (RDLS) is an important factor in describing the landform macroscopically. The distribution rule is elaborately expatiated in three separate ways: the ratio structure, the accumulative frequency, and the change along with the longitude and latitude, which clearly reflects the regional topographic framework of China. The result shows that the majority of the RDLS is low in China, for more than 63% of the area in China with the RDLS lower than 1 (relative altitude = 500 m). As for the spatial distribution, in general, the RDLS of the west is higher than that of the east and so is the south than the north. Specifically, the Hengduan Mountains and the Tianshan Mountains regions have the highest RDLS, while the Northeast China Plain, the North China Plain and the Tarim Basin have the lowest ones. The RDLS of 28°N, 35°N and 42°N as well as of 85°E, 102°E and 115°E accords well with the three topographic steps in China.

The RDLS of China decreases with the increase of longitude and the change clearly illustrates the landform characteristics that most of the mountains are located in the west and most plains in the east of China. The RDLS of China decreases with the increase of latitude as well and the trend shows that there are more mountains and hills in South China and more plains and plateaus in North China. In the vertical direction, the ratio of high RDLS increases with the increase of altitude. Finally, this paper analyzes the correlation between the RDLS and population distribution in China and the result shows that the RDLS is an important factor affecting the distribution of population and most people in China live in low RDLS areas. To be more specifically, where the RDLS is zero, the population amounts for 0.83% of the total; where the RDLS is less than 1 (relative altitude = 500 m), the population reaches 20.83%; where the RDLS is less than 2, the population amounts for 97.58% of the total; and where the RDLS is bigger than 3, the population only amounts for 0.57%. That is to say, more than 85% of the population in China lives in areas where the RDLS is less than 1 and less than 1% of the population lives in areas where the RDLS is bigger than 3.

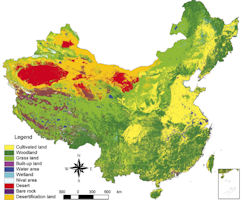

The composition and distribution of China’s land resources have three major characteristics: (1) variety in type -- cultivated land, forests, grasslands, deserts and tideland; (2) more mountains and plateaus than flatlands and basins; (3) unbalanced distribution: farmland mainly concentrates in the east, grasslands largely in the west and north, and forests mostly in the far northeast and southwest.

In China today, 135 million hectares of land are cultivated, mainly in the Northeast Plain, the North China Plain, the Middle-Lower Yangtze Plain, the Pearl River Delta Plain and the Sichuan Basin. The fertile black soil of the Northeast Plain is ideal for growing wheat, corn, sorghum, soybeans, flax and sugar beets. The deep, brown topsoil of the North China Plain is planted with wheat, corn, millet, sorghum and cotton. Plenty of lakes and rivers on the Middle-Lower Yangtze Plain make it particularly suitable for paddy rice and freshwater fish, hence its designation of “land of fish and rice”. This area also produces large quantities of tea and silkworms. The purplish soil of the warm and humid Sichuan Basin is green with crops in all four seasons, including paddy rice, rapeseed and sugarcane, making it known as the land of plenty. The Pearl River Delta abounds with paddy rice, gathered twice or three times every year.

Basins

There are many basins in China. Among them, the Tarim Basin, Junggar Basin, Qaidam Basin and Sichuan Basin are known as China's four major basins with different characteristics. Traditionally, China’s four major basins are the Tarim Basin in southern Xinjiang (about 400,000 square kilometers), the Junggar Basin in northern Xinjiang (about 300,000 square kilometers), eastern Sichuan, and the Sichuan Basin in western Chongqing (about 260,000 square kilometers) and the Qaidam Basin (about 250,000 square kilometers) in northwestern Qinghai. Geologically, the Ordos Basin (also known as the Shaanxi Ganning Basin, about 370,000 square kilometers), the Bohai-North China Basin (about 300,000 square kilometers), the Songliao Basin (about 260,000 square kilometers) and Qaidam Basin (approximately 260,000 square kilometers), Qiangtang Basin (approximately 220,000 square kilometers, excluding the central uplift zone is 160,000 square kilometers).

Plains

Due to the ups and downs of the earth's land surface, various terrains are formed. The basic terrain types include plains, hills, mountains, plateaus and basins. Plain refers to an area with an elevation of 200 meters or less, with little undulations on the surface, flat and wide area, and the plain terrain occupies about one-third of the total land area.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|