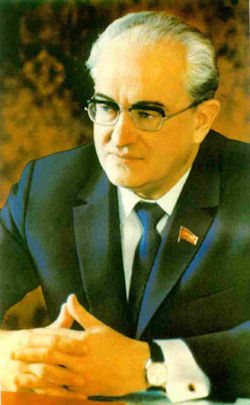

Andropov and Dissidents

Naturally, Andropov, as a communist and ideologist of the communist movement, was instructed to continue the persecution of political opponents among the dissidents who posed a potential threat to the system. Andropov felt this threat, although he understood her amorphism and lack of conformity. He was an opponent of Stalinism and mass repression,

Naturally, Andropov, as a communist and ideologist of the communist movement, was instructed to continue the persecution of political opponents among the dissidents who posed a potential threat to the system. Andropov felt this threat, although he understood her amorphism and lack of conformity. He was an opponent of Stalinism and mass repression,

In the late 1960s, Andropov restored the system of special departments in universities and enterprises that monitored public attitudes. In the apparatus of the Central Committee, departments for the struggle against ideological sabotage were liquidated, and their functions were assigned to the KGB. This did not mean a return to the monopoly role of the KGB, like Stalin's NKVD-MGB, but reinforced its importance. The KGB was supervised by one of the departments of the Central Committee of the CPSU, which drafted directives for all law enforcement agencies. At the same time, the reverse influence of the KGB on the system of power was reinforced. Andropov himself became a candidate member of the Politburo of the CPSU Central Committee.

Under Andropov, repressions against dissidents were somewhat reduced in quantitative terms, but intensified qualitatively. Criminal proceedings were conducted in the case of A. Ginzburg, Yu. Galanskov, A. Litvinov, L. Bogoraz, P. Grigorenko, N. Gorbanevskaya, R. Pimenov, B. Weil, A. Amalrik, V. Bukovsky. The geography of repressions expanded - arrests and processes took place on the territory of the Baltic states, Ukraine, Georgia, etc. Although the processes were closed, information about their progress seeped into the Western press and was brought to the population of the USSR through radio stations of the CIA, etc.

During this period, psychiatric "treatment" began to be applied, to which V.Bukovsky, P.Grigorenko, J.Medvedev, L. Ivy. Andropov sent a letter to the Central Committee with a plan for a more active use of the network of psychiatric hospitals in order to isolate active dissidents. The political abuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union originated from the concept that persons who opposed the Soviet regime were mentally ill because there was no other logical explanation why one would oppose the best sociopolitical system in the world. The diagnosis “sluggish schizophrenia,” an old concept further developed by the Moscow School of Psychiatry and in particular by its leader Prof Andrei Snezhnevsky, provided a very handy framework to explain this behavior. According to the theories of Snezhnevsky and his colleagues, schizophrenia was much more prevalent than previously thought because the illness could be present with relatively mild symptoms and only progress later.

And, in particular, sluggish schizophrenia broadened the scope because according to Snezhnevsky and his colleagues patients with this diagnosis were able to function almost normally in the social sense. Their symptoms could resemble those of a neurosis or could take on a paranoid quality. The patient with paranoid symptoms retained some insight in his condition but overvalued his own importance and might exhibit grandiose ideas of reforming society. Thus, symptoms of sluggish schizophrenia could be “reform delusions,” “struggle for the truth,” and “perseverance.”

For many Soviet psychiatrists this seemed a very logical explanation because they could not explain to themselves otherwise why somebody would be willing to give up his career, family, and happiness for an idea or conviction that was so different from what most people believed or forced themselves to believe. In a way, the concept was also very welcome because it excluded the need to put difficult questions to oneself and one’s own behavior. And difficult questions could lead to difficult conclusions, which in turn could have caused problems with the authorities for the psychiatrist himself.

The issue became prominent in the 1970s and 1980s due to the systematic political abuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union, where approximately one-third of the political prisoners were locked up in psychiatric hospitals. The issue caused a major rift within the World Psychiatric Association, from which the Soviets were forced to withdraw in 1983. They returned conditionally in 1989.

Andropov, unlike his predecessors in the state security, sought to send anti-Soviet intellectuals not to Siberian exiles and camps, but to European countries. At the same time, pressure was exerted on dissidents and their relatives to speed up their departure abroad. During this period, the emigration of Soviet Jews to Israel increased, during which a significant group of non-Jewish dissidents left the USSR. From immigrants and various defectors in Europe. The USA and Israel formed the "third emigration", which began to merge with the first - post-October and partially second - post-war. Those dissidents, who could not be convicted for various reasons and who did not want to leave the country, were expelled from the USSR almost by force (A.I.Solzhenitsyn).

Andropov was familiar with all the works of the human rights theorists and personally composed analytical notes for the Politburo on the moods among the intellectual opposition groups on the basis of which these or other decisions were prepared.

Andropov himself did not meet with dissidents, with one exception connected with the sensational case of P. Yakir and V. Krasin. These active dissidents were the sons of repressed "old Bolsheviks", who had spent many years in the camps and became leaders of the movement. They were subjected to repression by the KGB, during which the investigators managed to break their will to resist without the use of illegal methods and create conditions for cooperation with the KGB. Their surrender and further behavior in many ways demoralized the dissidents. After the trial, which sentenced Yakir and Krasin to three years in prison, the KGB planned a press conference with the participation of foreign journalists, which was to convince the public of the correctness of political power in its dispute with dissidents. During the preparation of this action Andropov met with the convicts. At the meeting, he said, that there will be no return to Stalinism, but no one will allow a legal and all the more illegal struggle against the Soviet power. Promising various indulgences and concessions, which were subsequently implemented, Andropov inclined Yakir and Krasin to cooperate. A press conference, held with great fanfare in the Moscow cinema hall "October", dealt a severe blow to the authority of the human rights movement, which declined numerically.

Andropov, in official speeches, argued that dissidents in the USSR are not a product of the Soviet way of life, but a consequence of the activities of Western special services using the renegades that are usual for any country. However, he understood that there was another real and most important source of resistance - the global political shortcomings of the Soviet system and large miscalculations in foreign and domestic policy, the disintegration of the nomenklatura elite, and the attempt at Stalin's rehabilitation.

According to the general opinion of historians and contemporaries, Andropov was perceived by the intelligentsia as a more free-thinking politician than all the other members of the party leadership. But in the 1970s, he not only did not criticize the regime, but also actively promoted its strengthening and tightening. What was it - insidiousness, intrigue, excessive caution, the expectation of one's time or all taken together?

The answer to this question provides additional information: firstly, the persecution of dissidents was sent from the Politburo of the CPSU Central Committee, which made personal decisions regarding Solzhenitsyn, Sakharov and other leaders of the movement; Secondly, Andropov's deputies to the KGB were absolutely loyal Brezhnev vigilant generals SK Tsvigun and GK Tsinev; thirdly, Andropov was able to help or mitigate the KGB's blow against such figures as R. Medvedev, E. Evtushenko, V. Vysotsky, M. Bakhtin. The Chairman of the KGB advised Roy Medvedev to continue work on the book on Stalin "To the Court of History" and only warned against publishing it abroad.

With Andropov's direct involvement, the Politburo's decision was made to allow the intelligentsia Literaturnaya Gazeta to have its own point of view that was different from the official position.

Andropov supported the demands of the leaders of the Crimean Tatars who were repressed under Stalin, who were not rehabilitated in the 1950s. In 1967, he held talks, as a result of which the Crimean Tatar people were rehabilitated and basically the basic civil rights were restored, except for mass return to their historical homeland - Crimea. At the same time, the KGB conducted the most determined struggle against nationalist currents in the Baltics, Ukraine, and the Caucasus. At that time, Jewish nationalist organizations began to show special activity, which acted in two directions: they created dissident human rights groups and organized the departure of Jews to Israel.

At the request of the KGB, special articles were introduced into the Criminal Code, which broadly interpreted the concepts of "anti-Soviet propaganda" and "slander against the Soviet social system," as well as articles that allow the extension and establishment of new terms for prisoners already convicted for these reasons. Andropov conducted the work purposefully and systematically and never showed even a shadow of remorse or regret.

There was a correspondence between Andropov and the physicist L. Kapitsa concerning the fate of AD Sakharov. In it, Andropov explains that Sakharov is being persecuted by the KGB for spreading over 200 materials in the West that contain "falsifications" of the policy of the USSR and are used by opponents of the USSR to stir up anti-Sovietism. This, according to Andropov, is no longer a dissent, but a concrete activity that threatens the political security of the USSR. With all sympathy for Academician Sakharov, one should recognize that in Andropov's position as a defender of the existing political regime there was a certain political meaning.

Over the years, when the KGB was headed by IA. Serov (from 1956 to 1958) for "anti-Soviet propaganda under article 58-10 of the Criminal Code of 1928, or, as they said later, for "dissent", 3,764 citizens were convicted, with A.N.Shelepin, already under Article 70 of the Criminal Code of 1960, - 1,442, and with V.E. Sevenfold - 600. For those 15 years, from 1967 to 1982, that the KGB of the USSR was headed by Yu.V. Andropov, according to article 70, a total of 552 people were convicted, and under article 190-1 another 1,353 people were convicted, that is, almost three times fewer than in the previous 10 years - 1,905 against 5,806 convicted.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|