The Age of Discovery

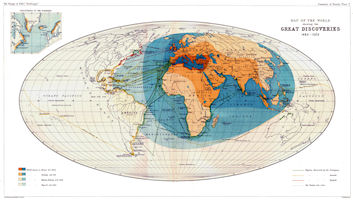

No activity of the Renaissance was more fruitful of important results than that having to do with maritime discovery and exploration. Early navigators, urged on by practical interests, began to feel their way down the coast of Africa, and to sail the Atlantic in search of those islands which had an existence in the literature of tradition, and to penetrate the region of the north. To call the fourteenth, fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the age of discovery is convenient, but arbitrary; for it cuts this era short at each end. On the one hand, the twelfth and thirteenth centuries really began the great era of discovery for they witnessed a genuine enlargement of the intellectual horizon in western Europe. On the other hand, the age of discovery has continued uninterrupted from the seventeenth century to the present time.

No activity of the Renaissance was more fruitful of important results than that having to do with maritime discovery and exploration. Early navigators, urged on by practical interests, began to feel their way down the coast of Africa, and to sail the Atlantic in search of those islands which had an existence in the literature of tradition, and to penetrate the region of the north. To call the fourteenth, fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the age of discovery is convenient, but arbitrary; for it cuts this era short at each end. On the one hand, the twelfth and thirteenth centuries really began the great era of discovery for they witnessed a genuine enlargement of the intellectual horizon in western Europe. On the other hand, the age of discovery has continued uninterrupted from the seventeenth century to the present time.

The great discovery came in the fourteenth century in northern Italy and came especially through the leadership of Petrarch (ft. c. 1345). At first the new interest was confined to the study of the books of pagan Rome and only later did it include the study of those of ancient Greece. The result was that brilliant period of nearly two centuries which is usually called the Italian Renascence. This revival of learning included an astonishing mastery of the Latin and Greek languages. But the geographical discoveries which began in the days of the crusades and reached their maximum extent in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, were one of the most powerful of the factors that revolutionized the thought of Europe.

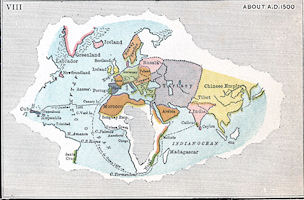

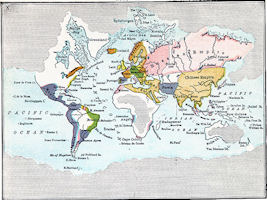

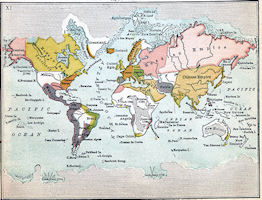

In the fifteenth century Portugal, still under the spell of the crusader's ideal and of the desire to outflank the Arab and no doubt also in search of wealth, began to explore the western coast of Africa. In a few decades this enterprise led Portuguese sailors to the southernmost cape of Africa and beyond to the settlements of Arabian colonies on the eastern coast; and in 1497 the greatest feat of seamanship ever attempted began in the departure of Vasco da Gama from Lisbon for India. Then the Mohammedan was completely outflanked; and in a few years the Portuguese admirals with their far superior ships and seamanship commanded the Indian trade, and the old trade route via the Levant, with its costly and difficult methods of transit, had become hopelessly inferior to the ocean route. In the meantime the search for a direct western route to India, misled by the exaggerated estimate of the longitudinal width of the Euro-Asian continent obtaining since the days of Ptolemy, led to the discovery of America and by 1521 to the circumnavigating of the globe.

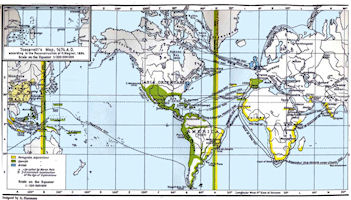

It is clearly established that by the opening of the fifteenth century there was a lively interest, particularly among the peoples of the Mediterranean lands, in such enterprises as were undertaken for the purpose of opening up communication with remote regions of the earth. Here there was a veritable renaissance of geography. The oldest maps of real value, which seem to owe their origin to these newly-awakened interests, are the portolanos or coast charts, constructed at first for the region of the Mediterranean. These portolanos were the work of the sea-faring peoples of Italy and the coast districts of the western Mediterranean, who were the immediate precursors of the trans-Atlantic explorers, and they possess a real value, in striking contrast with the world-maps of the Middle Ages — an individuality which insured them for many years a place of commanding importance. They form the basis of many of the maps in which the New World is first presented.

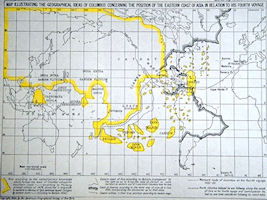

When Chrysoloras and Aurispa, with their companions among the early Humanists, were introducing into Italy the re-discovered literature of Ancient Greece, along with their treasures came the text of Ptolemy's Geography. It had the effect of an important discovery, which seized men's minds, at first with even more force than the discovery of the New World by Columbus. Not a new world, but the very world in which one was living, had been extricated from the darkness in which it had been hidden during a whole millennium. Ptolemy became anew the teacher of geography to the peoples of Europe, and his authority was very tardily called in question even after the discovery of the New World. Long after the region had been explored lying beyond the world of which Ptolemy had knowledge, the work of that Alexandrian geographer was in great favor.

A study of modern cartography should begin with Ptolemy — the Ptolemy of the Renaissance. No less than thirty editions of his work were printed before 1570, and of these twenty-six contain about 700 old Ptolemy maps and about 400 tabulae novas. If a comparison is made with the small number of maps which were printed before the year 1570, some impression of the influence of the Alexandrian geographer, after fourteen hundred years had passed, may be gained. The oldest known copy of his work, to which in addition to the usual 27 maps new maps have been added, is found in the library of Nancy, France. Considering Greenland to be a part of the western continent, here is one of the oldest known maps in which any part of the New World appears. It is stated in the accompanying text that it is the work of Claudius Clavus, and it is probably based upon the observations of northern explorers. Though a sketch far from accurate in its details, it has the merit of exhibiting accurately the relative position of Iceland and Greenland, that which is not true generally of the maps of Columbus's day.

A study of modern cartography should begin with Ptolemy — the Ptolemy of the Renaissance. No less than thirty editions of his work were printed before 1570, and of these twenty-six contain about 700 old Ptolemy maps and about 400 tabulae novas. If a comparison is made with the small number of maps which were printed before the year 1570, some impression of the influence of the Alexandrian geographer, after fourteen hundred years had passed, may be gained. The oldest known copy of his work, to which in addition to the usual 27 maps new maps have been added, is found in the library of Nancy, France. Considering Greenland to be a part of the western continent, here is one of the oldest known maps in which any part of the New World appears. It is stated in the accompanying text that it is the work of Claudius Clavus, and it is probably based upon the observations of northern explorers. Though a sketch far from accurate in its details, it has the merit of exhibiting accurately the relative position of Iceland and Greenland, that which is not true generally of the maps of Columbus's day.

Germanus’ world maps served as the model for Martin Behaim’s celebrated 1492 globe.

These geographical discoveries gave Europe a host of new interests, or subjects of thought. This alone implies that the new subjects competed successfully with the old and that the old interests became less prominent. And one of the evident facts in medieval thought was the almost exclusive theological interest. But these new interests were not mere rivals of the old; for they raised numberless new and important problems, and they led men to correct numerous errors of the older learning. For example, to know the customs of other lands makes one critical of the customs of one's own land. To know the radically different thoughts and morals of other people makes one see that numerous principles which before were accepted as self-evident are mere assumptions.

Germanus’ world maps served as the model for Martin Behaim’s celebrated 1492 globe.

These geographical discoveries gave Europe a host of new interests, or subjects of thought. This alone implies that the new subjects competed successfully with the old and that the old interests became less prominent. And one of the evident facts in medieval thought was the almost exclusive theological interest. But these new interests were not mere rivals of the old; for they raised numberless new and important problems, and they led men to correct numerous errors of the older learning. For example, to know the customs of other lands makes one critical of the customs of one's own land. To know the radically different thoughts and morals of other people makes one see that numerous principles which before were accepted as self-evident are mere assumptions.

It was no accident then that the intellectual men of Europe two centuries after Columbus and Vasco da Gama questioned almost every institution, custom, religious dogma and moral principle of the medieval tradition, that they believed men are the mere product of their environment and that therefore environment if rightly chosen can make men perfect. It was no accident that they thought civilization an artificial structure and that the natural man as opposed to the civilized man formed the basic man of so many of their political, moral, religious and educational theories.

Finally, these discoveries filled parts of Europe with the very spirit of adventure and they made people more tolerant and expectant of change in every department of life. Picture the effect of these early discovered worlds upon the adventurous members of the European population, an effect comparable to that of the discovery of gold in Australia, California and the Klondike. Picture the frequency with which extraordinary news must have been received in the busy seaports of western Europe and the growing response to novelty itself as a matter of course. True, these facts do not imply that all of Europe became radically minded or that any place became radically minded in all things. But they do imply that the geographical discoveries alone go far to explain the tremendous change that came as a matter of fact over the intellectual life of Europe in the course of the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|