Prester John

Prester John was the name of a potent Christian monarch of shadowy renown, whose dominions were placed by writers of the middle ages sometimes in the remote parts of Asia and sometimes in Africa, and of whom such contradictory accounts were given by the travellers of those days that the very existence either of him or his kingdom came to be considered doubtful. The reason why all former inquiries with respect to Prester John led to no result may be ascribed to the circumstance that more attention was paid to the explanation of the name than to the historical facts.

Prester John was the name of a potent Christian monarch of shadowy renown, whose dominions were placed by writers of the middle ages sometimes in the remote parts of Asia and sometimes in Africa, and of whom such contradictory accounts were given by the travellers of those days that the very existence either of him or his kingdom came to be considered doubtful. The reason why all former inquiries with respect to Prester John led to no result may be ascribed to the circumstance that more attention was paid to the explanation of the name than to the historical facts.

The title of Presbyter Johannes was in the middle ages held in great respect, as it was then often announced that the end of the world was near, and the adherents of the Millennium were waiting for the arrival of the Presbyter Johannes as the precursor of Christ. What makes the Presbyter Johannes so important to history and geography is that the voyages which led to the discovery of the Cape of Good Hope and of the seaway to the East Indies were undertaken in search of that mysterious Prince, as can be proved by the orders given to Bartolomeo Diaz. The Portuguese were determined to find Prester John, and hoped to link up with him by sailing around Africa.

The first vague reports of a Christian potentate in the interior of Asia, or as it was then called, India, were brought to Europe by the Crusaders, who it is supposed gathered them from the Syrian merchants who traded to the very confines of China. In subsequent ages, when the Portuguese in their travels and voyages discovered a Christian king among the Abyssinians, called Baleel-Gian, they confounded him with the potentate already spoken of. Nor was the blunder extraordinary, since the original Prester John was said to reign over a remote part of India; and the ancients included in that name Ethiopia and all the regions of Africa and Asia bordering on the Red Sea and on the commercial route from Egypt to India.

The first chronicle in which the name of Presbyter Johannes occurs, is that compiled by Otto, Bishop of Freisingen in Bavaria, a grandchild of the Emperor Henry IV, a half-brother to the Emperor Konrad III, and uncle to Frederick Barbarossa. Otto relates that a powerful king, called the Presbyter Johannes, had defeated in a most sanguinary battle the Samiardos fratres, the kings of Persia and Media. Sultan Sanjar, together with his brothers, reigned in the western part of Asia, and the word "Samiar" is nothing else than the name Sanjar.

The first chronicle in which the name of Presbyter Johannes occurs, is that compiled by Otto, Bishop of Freisingen in Bavaria, a grandchild of the Emperor Henry IV, a half-brother to the Emperor Konrad III, and uncle to Frederick Barbarossa. Otto relates that a powerful king, called the Presbyter Johannes, had defeated in a most sanguinary battle the Samiardos fratres, the kings of Persia and Media. Sultan Sanjar, together with his brothers, reigned in the western part of Asia, and the word "Samiar" is nothing else than the name Sanjar.

Otto had received the news through the Syrian bishop of Gabala, who had come to Asia to ask for assistance against the growing power of the Atabek Zenky, who had taken possession of the strong city of Edessa. Before leaving Asia, the Bishop of Gabala had been beleaguered by the Greek Emperor Johannes Comnenus in Antioch, for the prince of Antioch, Raimund, had refused to allow the Emperor to march with his troops through his territory.

It is this siege which is mentioned by the famous traveller William Rubruquis as coeval with the appearance of a mighty Prince in the North, named Coirchan of Kara khatai. The title of the Prince of the Kara-Kitai was Korkhan, which means the Khan of the Khans, the Supreme Khan, or, according to another explanation, may also signify the Lord of the People. This title was used in the same way as that of Pharaoh by the Egyptian kings. The first K in Korkhan is a Kaf, which in the Turkish languages can be pronounced as K, G, or J. Gorkhan or Jorkhan sounds to the Syrian ear very much like Jokhan or Jochanan, which is the Syrian form for Johannes. This being the case, it is easy to see how the Bishop of Gabala could call the Kitai Korkhan, Johannes or John.

But this John is further described as a Nestorian and a Presbyter. Now it is generally known that the Nestorian missionaries were spread over Central Asia and China, and the respectable evidence of William Rubruquis, who states that the Nestorian bishops, appearing seldom in their sees, consecrated to the priesthood each male, even the children in the cradle. The Persian historian Mirkhond distinctly remarks that the daughter of the last Korkhan was a Christian.

At the time when the rumor of this prince reached Western Asia and Europe, the Crusaders were in a very bad position. Stronghold after stronghold had fallen into the hands of the Moslems, and despair began to fill their hearts. Is it therefore astonishing, when the defeat of their fiercest enemy Sultan Sanjar excited the most sanguine hopes, that reports from the East supported the excitement of expectation, and the simple truth was- shaped into marvellous forms? We have thus to understand that singular letter of Prester John, which was received by the Pope, the Emperors of the East and West, and other sovereigns, as those of France and Portugal. It is without the least doubt spurious; but it is of importance, as it shows how easily men could be imposed upon during the middle ages. Though the most heterogeneous things are reported in it, this letter seemed on the whole nothing but a bad copy of the wonderful letter of Alexander the Great to his mother Olympias, which we find in the work of Pseudo-Kallisthenes. In the voyages and travels of Sir John Maundeville we meet with a very extensive and amusing account of these tales.

But if that letter was spurious, repeated news and reports induced Pope Alexander III to write a letter to Prester John. It is dated 27 September, 1177, and signed at the Rialto in Venice. His friend and physician Philippus was charged with its safe delivery; and though this ambassador had previously been in the empire of the Korkhan, and knew much about it, it is not known what became of Philippus and his letter. Poetry soon possessed itself of this interesting personage, and the epics and romances of the middle ages abound with descriptions of the splendor of Prester John.

From the twelfth century onwards the famous Prester John was supposed to be the greatest and most prosperous of all kings, not only have the greatest appearance of probability among all the accounts that are given of him, but are also supported by the testimony of writers of candor, and the most worthy of credit; namely, William of Tripoli, (see Carolus Du Fresno, notes to Joinville's Life of St. Lesris, p. 89.) the bishop of Gabul, in Otto of Frisingen's Chronicon, lib. vii. c. 33.

From the twelfth century onwards the famous Prester John was supposed to be the greatest and most prosperous of all kings, not only have the greatest appearance of probability among all the accounts that are given of him, but are also supported by the testimony of writers of candor, and the most worthy of credit; namely, William of Tripoli, (see Carolus Du Fresno, notes to Joinville's Life of St. Lesris, p. 89.) the bishop of Gabul, in Otto of Frisingen's Chronicon, lib. vii. c. 33.

This bishop had come to Rome to obtain the decision of an umpire of the controversies between the Armenian and Greek churches. On this occasion he related, that a few years before, one John who lived in the extremities of the east, beyond Persia and Armenia, and was both a king and a priest, had, with his people, become a Nestorian christian ; that he had vanquished the Median and Persian kings, and attempted to march to the aid of the church at Jerusalem, but was obliged to desist from the enterprise, because he was unable to pass the Tigris. This king was descended from the Magians mentioned in the gospel, and was so rich that he had a sceptre of emerald. Seld.) William Rubruquis, Voyage, c. xviti. p. 36, in the Antiqua in Aeiam Itinera, collected by P. Gerberon ; and Alberic, Chronicon, ad atrn. 1165 and 1170 ; in Leibnitz's Accessiones Historicce, tom. ii. p. 345 and 355, and others.

It is strange that these testimonies should have been disregarded by learned men, and that so many opinions and disputes should have arisen respecting Prester John and the region in which he lived, and should have continued down even to our times. But such is the human character, that what has most simplicity and plainness, is despised, and what is marvellous and obscure is preferred.

Joseph Scaliger contends that Prester John, which is in Italian Preste Giani, stands for the Persian word Prestegiani; Padesha prestegiani means therefore an Apostolic or Christian king. Another scholar explained it by Prester Chan, or the Chan of the Adorers or Christians. Tzaga Zabus converts Presbyter Johannes into Pretiosus Johannes (Precious John, or John possessing precious things)—a name still to be found on old maps of Abyssinia. Cornelius a Lapide contends that Preste or Prete is the Portuguese Preto (black), and that Preto Joan means Black John, a name for the Abyssinian Emperor. Paulus Guicius calls Prester John Pedro Juan, or Peter John; and the famous scholar Sebastian Miinster, a contemporary of Luther, makes of him a Presbyter Kohan or Presbyter Kohn.

By some German poets the legend of Prester John has also been mixed up with that of the San-Gral. Wolfram von Eschenbach and Albrecht von Scharffenberg contend that the San Gral went to Prester John when the .West was not deemed holy enough to keep the precious treasure. In the Parcival of Wolfram, the Gral is described as a stone by which the knights of the Gral are fed, with which the Phoenix burns himself, ana whose knights, who are called Templars, defend the castle of Salvatierra.

Nestorian Christian

The first Prester John was succeeded by four sovereigns of his family, who all reigned prosperously, till the last, Jiluku by name, was shamefully deposed by his own son-in-law, a Nayman prince, who had previously found at the Court of the Korkhan shelter from the persecution of Tchingyzkhan and had received the hand of the Princess Imperial, the heiress to the throne, and who now showed his gratitude by ousting his benefactor. Rubruquis mentions that the last Korkhan was succeeded by a Prince of the Nayman tribe, who also took the title of Prester John. Kushluk only reigned as Korkhan or Prester John a few years (from 1213 to 1218), when he was totally defeated by the troops of Tchingyzkhan and killed while flying from the field.

The French monk and ambassador sent by Pope Innocent in 1245 to the Great Khan, Johannes de Plano Carpini, passed through the valley in which Kushluk was defeated. According to him, Prester John was originally a Nestorian priest, who on the death of the sovereign made himself King of the Naymans, all Nestorian Christians. With him became extinct the princes who had the title of Korkhan of Kara-Kitai, and he was the last prince of that empire, though himself only a usurper. Another dynasty of Kara-Kitai princes settled for some time, from 1224 to 1364, in Kirman; but the memory of the empire of the Korkhan soon passed away, and when the European travellers passed through Asia, the existence of the Korkhan or real Presbyter Johannes had already assumed a mythical aspect. The rapid progress of the Mongolic conquests and the entire overthrow of all the previous empires, and of the whole political state of Asia, explain in some degree why there exists no trustworthy history of these times, and how a manifest falsification of history could have been made and supported even up to the present day.

The Archbishop of Peking, Johannes de Monte Corvino, could speak in his letter, dated from Peking, on the 8th of January, 1305, of a neighbouring king Georgius, a descendant of Prester John, with whom he stood on very intimate terms; and who, persuaded by his preaching, had left the Nestorian church, had become a Roman Catholic, was consecrated by him a priest, and used to administer in his royal garments during the service. This king Georgius was followed by his son Johannes, a godson of the archbishop. Marco Polo, too, mentions this king Georgius as the fourth (according to others as the sixth) in descent from Prester John, of whose family he is regarded as the head.

It appears to be admitted by some in the 19th Century that there really was such a potentate in a remote part of Asia. He was of the Nestorian Christians, a sect spread throughout Asia, and taking its name and origin from Nestorius, a Christian patriarch of Constantinople. It is said that in Asiatic Tartary, near to Cathai, a great revolution took place, near the beginning of the 12the Century, and a revolution very favorable to the cause of Christianity. For on the death of Coiremchan, or as others call him, Kenchan, a very powerful king of the eastern regions of Asia, at the close of the preceding century, a certain priest of the Nestorians inhabiting those countries, whose name was John, made so successful an attack upon the kingdom while destitute of a head, that he gained possession of it, and from a presbyter became the sovereign of a great empire.

This was the famous Prester John, whose country was for a long time deemed by the Europeans the seat of all felicity and opulence. Because he had been a presbyter before he gained the kingdom, most persons continued to call him Prester John after he had acquired regal dignity.

His regal name was Ungchan. The exalted opinion of the power and riches of this Prester John, entertained by the Greeks and Latins, arose from this, that being elated with his prosperity and the success of his wars with the neighbouring nations, he sent ambassadors and letters to the Roman emperor Frederic I., to the Greek emperor Manuel, and to other sovereigns, in which he extravagantly proclaimed his own majesty and wealth and power, exalting himself above all the kings of the earth: and this boasting of the vain-glorious man, the Nestorians labored with all their power to confirrn. He was succeeded by his son or brother, whose proper name was David, but who was also generally called Prester John. This prince was vanquished and slain, near the close of the century, by that mighty Tartar emperor, Genghishan.

The Abyssinian Negus

The idea that a Christian potentate of enormous wealth and power, and bearing this title, ruled over vast tracts in the far East, was universal in Europe from the middle of the 12th to the end of the 13th century; after which time the Asiatic glory seems gradually to have died away, while the Royal Presbyter was assigned to a locus in Abyssinia, the equivocal application of the term India facilitating this transfer. When Marco Polo made his famous journey to the East, he found a loosely organized Christian tribe in central Asia, not the powerful kingdom that Europeans had expected to find there. The Prester John legend had lost popularity among Europeans -- until 1310, when King Wedem Ra'ad of Ethiopia, a Coptic Christian, sent an ambassador to Europe. Here was a ruler who seemed to match the description of Prester John exactly...but in Africa, not Asia. From that time on, Prester John's kingdom was placed in Ethiopia, and its ruler's descent traced from Solomon and the Queen of Sheba.

The idea that a Christian potentate of enormous wealth and power, and bearing this title, ruled over vast tracts in the far East, was universal in Europe from the middle of the 12th to the end of the 13th century; after which time the Asiatic glory seems gradually to have died away, while the Royal Presbyter was assigned to a locus in Abyssinia, the equivocal application of the term India facilitating this transfer. When Marco Polo made his famous journey to the East, he found a loosely organized Christian tribe in central Asia, not the powerful kingdom that Europeans had expected to find there. The Prester John legend had lost popularity among Europeans -- until 1310, when King Wedem Ra'ad of Ethiopia, a Coptic Christian, sent an ambassador to Europe. Here was a ruler who seemed to match the description of Prester John exactly...but in Africa, not Asia. From that time on, Prester John's kingdom was placed in Ethiopia, and its ruler's descent traced from Solomon and the Queen of Sheba.

Peter Covillanus, who was directed in the fifteenth century by John II, king of Portugal, to make inquiries respecting the kingdom of Prester John, when he arrived in Abyssinia with his companions, on discovering many things in the emperor of the Abyssinians or Ethiopians analogous to what was then currently reported in Europe respecting Prester John, supposed that he had discovered that John whom he was ordered to inquire after. And he easily persuaded the Europeans, then scarcely emerged from barbarism, to fall in with his opinions. See John Morin, de Sacris Ecclesice Ordinat'ionibus, pt. ii. p. 367, &c.

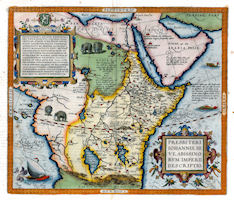

The modern Abyssinia, a highland country of eastern Africa, containing the source of the Blue Nile; its territory was part of ancient Ethiopia. Ortelius begins his account of Abyssinia as follows: "He whom the Europeans call Prester John is called ... by his Abyssinian subjects . . . Negus, that is, Emperor and King." The so-called Prester John map was added to Ortelius’s landmark atlas in the 1573 editions. The many notes added by Ortelius provide insights into the prevailing myths of the time. For example, he says that the Niger River, shown flowing north from Lake Niger (Niger lacus), goes underground for sixty miles and emerges in Lake Borno (Borno lacus); that sirens and sea gods live in Lake Zaire (Zaire lacus); and that the sons of Prester John were kept captive by rulers at Mount Amara (Amara mons).

But in the seventeenth century, many writings having been brought to light which had been unknown, the learned in great numbers abandoned this Portuguese conjecture, and agree that Prester John must have reigned in Asia ; but they still disagreed as to the location of his kingdom and some other points. Yet there were some among the most learned men, who chose to give credit to the Portuguese, though supported by no proofs and authorities, that the Abyssinian emperor was that mighty Prester John, rather than follow the many contemporary and competent witnesses.

See Euseb. Renaudot, Historia Patriareh. Alexandria p. 223. 337. Jos. Franc. Lafitau, Histoire del DUoasertes da Portugais, tom. i. p. 58, and tom. iii. p. 57. Henr. Le Grand, Dies. de Johanni Presbyt. in Lobo's Voyage d'Abminie, tom. i. p. 295, &c. [Mosheim's Historia 1'artaror. Eccles. p. 16, &c. Baronius, Annales, ad ann. 1177- § 55, gives the title of an epistle written by pope Alexander III. to Prester John, which shows that he was an Indian prince, and a priest: "Alexander Episcopus, servus servorum Dei, charissimo in Christo filio illustri et magnifico Indorum regi, sacerdotum sanctissimo, salutem et Apostolicam benedictionern."

Nor was the blunder extraordinary, since the original Prester John was said to reign over a remote part of India; and the ancients included in that name Ethiopia and all the regions of Africa and Asia bordering on the Red Sea and on the commercial route from Egypt to India.

The Dalai Lama

That the Dalai Lama was the Prester John, is denied by Paulsen, the real author of Mosheim's Hist. Tartaror. Ecclesiastica. Yet subsequently Joh. Eberh. Fischer, in his Introduction to the History of Siberia, p. 81, (in German,) maintained this opinion ; and endeavoured to show, that the Dalai Lonna (Lama), and Prester John, are the same person; and that the latter name is a fictitious word.

Prester John was heard-of earlier than the Dalai Lama. In the country of the Mongouls, where Prester John was said to have formerly resided, they knew nothing about a Dalai Lama before the time of Kajuk-khan, one cf the descendants of Tschingis-khan f. Among the Europeans, Pere Andrada is one of the first who mentions him, about the year 1624, and Bernier speaks of him as of a strange novelty. It deserves to be remarked, that the old Writers, while they take notice of the Nestorians and Prester John, say not a syllable of the Dalai Lama. But no sooner are they become acquainted with the Dalai Lama, than they cease all mention of Prester John and the Nestorians in Mongolia and Tibet.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|