Pokhran Photographic Interpretation Report

Recently acquired high-resolution IKONOS imagery from SpaceImaging discloses surprisingly few features that would be readily associated with multi-kiloton underground nuclear test activity at the Khetolai military range.

The Great Indian Desert of western India is the most densely populated hot desert in the world. This geographic feature is known as the Thar Desert in Pakistan, a derived from t'hul, the general term for the region's sand ridges. The desert consists of rolling sand dune separated by sandy plains and punctuated by low, barren hills [called bhakars]. Although in some areas the sand dunes are in continual motion, older dunes are in a semistabilized condition and may rise to a height of 150 meters. The land is barren, dry and hostile, and rainfall is scanty and erratic. Vast expanses of sparse vegetation include stunted scrub with occasional trees, along with the grasses provide sustenance for cattle, sheep and goats. Camel are commonly used for transport. This desert region of Rajasthan State receives most of its rainfall from the southwest monsoon from June to September. In the area near Jodhpur, in central Rajasthan State, on average about 370 mm of precipitation is received during the summer monsoons. These rains begin in June and last only about 11 weeks. The probability of severe drought in this area (as occurred in 1985-87) is calculated at 40 percent. Irrigation water is now available following the completion of the Indira Gandhi Canal in western Rajasthan. However, dryland farming practices, where water for plant growth is supplied entirely by rainfall, still predominates. The vast majority of the population live in dusty villages of less than 5,000 people or in scattered hamlets and other small rural settlements located between sand dunes and infertile expenses of landscape. About 20 percent of the total area is under cultivation, mostly in Haryana and Gujarat states, and comparatively little in Rajasthan.

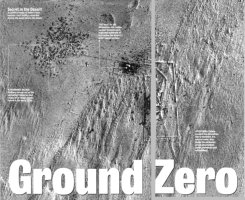

Although the exact locations of the 1998 tests are most certainly now known to the US intelligence community, their exact location remained something of a mystery in the open literature. Soon after the tests, Newsweek magazine published a Russian KVR-1000 image that was represented to be the Indian test site. The image, which was reportedly acquired during the week before the tests, depicted a different area from the Khetolai military range studied by Gupta and Pabian. The annotation of the imagery, which was said to have been provided by informed consultants engaged by Newsweek, included identification of a single underground test shaft, a nearby support area surrounded by a security perimeter, and an abandoned village. Although the exact location was not reported, the overall appearance of the terrain is entirely consistent with that of the Rajasthan desert surrounding Pokhran and the Khetolai military range, including the distinctive north-facing sand dunes.

| Pokhran Test Range - as depicted in Newsweek

|

|

Annotation from Newsweek - 1998 |

Annotation from Newsweek - 1998 |

The source of the Newsweek annotation of this imagery is obscure, although presumably this large news organization engaged in some vetting process prior to giving such prominent play to this imagery. It may be assumed, although it is not known, that the annotation included input from informed sources who had direct knowledge of the location and appearance of the actual Indian test site.

Soon after the prominent publication of this image, Newsweek dis-avowed the original report. Curiously, the claimed "nuclear test site" had been noted two years earlier by Gupta and Pabian, whose analysis of a May 24, 1992 KVR-1000 image led them to concluded that this site near the village of Sri Bhadria was an enclosed agricultural facility. The area identified by Newsweek as the underground test shaft was indentified by Gupta and Pabian as animal pens.

This episode is frequently cited as the exemplar of the hazards attendant on the exploitation of commercial imagery. Although the precise origins of Newsweek's mistaken identity remain obscure, their methodological shortcomings are evident. Even a cursory review of the existing literature would have disclosed the Gupta and Pabian analysis, which should have cautioned against the temptations of over-interpretation. More fundamentally, however, this exploit sought to depict the location of a future event, rather than examine the signatures of a past event. In the absence of robust collateral information, it is evidently vastly more difficult to discern the signatures of coming attractions than those of accomplished facts.

Unavoidably, however, any future public imagery analysis of the Pokhran nuclear test stands in the shadow of Newsweek's mistaken identity.

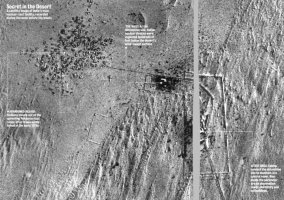

The overall appearance of the Pokhran range is much as it was described by Gupta and Pabian in their 1996 analysis. The stability of the sand dunes in this area is evident in the almost complete absence of change in landscape features over the four years intervening between the 1996 SPIN-2 image and the 2000 IKONOS image. Indeed, it is possible to identify most of the individual trees and scrub brushes present in the 1996 image in the 2000 image.

The most striking difference between the 1996 SPIN-2 image and the 2000 IKONOS image is the pronounced contraction in the vegetation anomaly associated with the various security perimeters that encircle the Khetolai military range. The vegetation anomaly is created by the exclusion of grazing livestock from the secured area by the security perimeter. In the 1996 image this vegetation anomaly is triangular, with each side of the roughly equilateral triangle extends for about five kilometers. In the 2000 IKONOS image, the security perimeters that bound the range remain in evidence, but the vegetation anomaly has contracted to a lozenge some one by two kilometers in extent. It is not apparent whether this represents an opening of the security perimeters to admit grazing livestock, or whether it merely represents a seasonal variation in vegetation density. The SPIN-2 image was acquired on 01 June, around the beginning of the monsoon rains, while the IKONOS image was acquired on 03 February, nearly five months after the end of the monsoon.

Available imagery brackets the May 1998 tests by two years -- the June 1996 SPIN-2 image was collected nearly two years prior to the tests, while the February 2000 IKONOS image was collected nearly two years after the tests. Evidently higher confidence in identifying test-related activities could be derived from imagery that immediately pre-dated and post-dated the tests, but such imagery is not known to be commercially available.

The possibility cannot be excluded that India has substantially modified the surface appearance of one or more test locations. It is known that Pakistan substantially modified the Kharan Desert site of its second underground test, though the reasons for this modification are obscure. The fact of the Pakistani modifications to their test area is well attested, and Pakistan made no effort to restore the test area to a pristine pre-shot condition. It is possible that subsequent site modifications at one or more Indian test locations might produce an appearance that would be at substantial variance with the immediate post-shot appearance of the site. However, it is noteworthy that India apparently did not subsequently modify the surface appearance of the site of the 1974 test. It is unlikely that India would modify the surface appearance of a test site to restore the precise pre-test surface appearance, to include replacing small shrubs to their exact pre-test location.

| Satellite Imagery of the Khetolai Military Range |

|

Khetolai Military Range SPIN-2 IMAGERY 01 June 1996 |

Khetolai Military Range IKONOS IMAGERY 03 February 2000 |

Considerable art was required on the part of Gupta and Pabian to discern with confidence the location of the 1974 test crater. This crater is clearly evident in both the 1996 SPIN-2 imagery and the higher resolution February 2000 IKONOS imagery. The subsidence area proper has a radius of about 60 meters, and is surrounded by a distinctive heart-shaped perimeter with a radius of roughly 80 meters. There is little evidence of modification of this site between 1996 and 2000. Imagery of this crater provides an important baseline in the search for at least the multi-kiloton test[s] conducted in May 1998. Although the precise yields of these tests remains controversial, it is generally agreed that the yields of two of the May 1998 tests were of the same order of magnitude as that of the 1974 test, and presumably should have produced subsidence craters and associated surface features of roughly the same magnitude and overall appearance.

| Satellite Imagery of 1974 Nuclear Test Crater

|

|

1974 Nuclear Test Crater SPIN-2 IMAGERY 01 June 1996 |

1974 Nuclear Test Crater IKONOS IMAGERY 03 February 2000 |

There is nonetheless some uncertainty as to the scale and structure of post-test surface features expected to have resulted from India's 1998 tests. Presumably the devices were buried at sufficient depth to contain radioactive debris from the detonations, and presumably India did not go to the extra effort that would be required to bury the devices at significantly greater depth than would be required for debris containment alone. However, unavoidably there is some uncertainty associated with predicting the yield of untested nuclear weapons designs, and India may have decided to emplace the test devices in shafts that were sufficiently deep to contain detonations at the upper end of the expected yield. If the actual detonations were significantly below the expected yield, the depth of burial of the device could be so great as to produce a rather smaller and less distinct surface expression than might otherwise be expected. Certainly the 1974 subsidence crater presents a less symmetrical appearance than many subsidence craters at the American test site in Nevada. This feature has been advanced as possibly indicative that the yield of the 1974 test was less than anticipated and announced, and that consquently the device was "overburied." But this chain of reasoning sustains the connection between the scale and appearance of the 1974 crater and those produced by the multi-kiloton 1998 tests, since the contention that the yields of the 1998 tests were less than announced is in part predicated on a belief that the yield of the 1974 was also less than announced. Although the absolute values of the explosive yield of the tests are not reliably known, their relative magnitude is, leading to an expectation of subsidence craters from the larger of the 1998 tests that are comparable to that of the 1974 test.

There is, however, no fundamental constraint on the depth of the shafts in which India might have conducted its underground nuclear tests, and a variety of factors might have been taken into consideration in drilling the shafts for tests. The open literature strongly suggests that the shafts had been completed well in advance of the tests, and it is possible that the shafts were initially sized to accomodate the highest yield device that might have been expected to be tested in the future. Thus, the shafts might have been sized to accomodate significantly higher yield deviced than were in fact tested. Or, India might have sought to err on the side of caution, and emplace the test devices rather deeply, to minimize subsequent radiological hazards. And it is possible that India buried its bombs deeply to frustrate independent estimates of their planned or actual yields [if this was their goal, they would have appear to have achieved considerable success].

The Government of India released a number of photographs of the site of the May 1998 tests, and these should be of some use in identifying the locations of these tests in available satellite imagery. India claimed to have tested a total of five nuclear devices, and released photographs that apparently depicted five different test areas. In practice, the single photographs of two test areas [arbitrarily designated here as Test Area D and Test Area E ] lack sufficient detail to be of much value. The photos of the test site arbitrarily designated here as Test Area C apparently depict the edge of a subsidence crater located in an area of sparse vegetation, though no other interpretive details are evident. The photos of the test site arbitrarily designated here as Test Area B apparently depicts the above-ground headworks of a low-yield underground test. Although no subsidence is in evidence, the test area is centered on a structure and located within a distinctive vegetation pattern -- features which should assist in identifying this area in satellite imagery.

The test site arbitrarily designated here as Test Area A has been associated by the Government of India with the highest yield test conducted on 11 May, and the released photographs are the most informative of the entire series. Although the test area presents a surprisingly jumbled appearance, it would appear that the subsidence crater has a depth of about 10-15 meters, and a radius of somewhat over 30-40 meters [though the radius is difficult to estimate from available ground-truth photography]. While the depth is generally consistent with that of the 1974 crater, the apparent radius of the subsidence area is rather smaller.

Gupta and Pabian identified the area they designated as Site A as a possible underground nuclear test site. Both Site A and Site C are surrounded by multiple layers of perimeter barriers, and have a rectangular structures which intersects the inferred cable lines at the center of the fenced perimeter. This fits the profile of a underground nuclear test shaft location, and the configuration resembles the layout that was used for vertical shaft tests at the US Nevada Test Site.

A comparison of the 1996 pre-test SPIN-2 imagery and the 2000 post-test IKONOS imagery discloses a number of changes in the appearance of this site, although the overall configuration remains largely unchanged. The outer perimeter that defines the site remains essentially unchanged. In the 1996 SPIN-2 image the site support area and the access roads are consistently clear of vegetation, whereas in the 2000 IKONOS image much of the access area appears dis-used, though the access roads remain clearly defined.

The most striking changes are evident towards the center of this site. In the 1996 image there is a roughly rectilinear assemblage of four roughly rectilinear unresolved features, anchored at the center of the site and oriented towards the northeast. Each of these four features is approximately 10 meters by 30 meters in extent, and their general location and appearance is not inconsistent with berms, sheds, or kindred features that are typical of test areas of various types. However, the nature and function of these features cannot be resolved with available imagery.

Three of these four features are entirely absent from the February 2000 IKONOS image, though the possible remnants of the fourth feature at the northern edge of the site can be discerned. This higher resolution imagery provides no further insight into the nature of these features. The central area of the site is now defined by a barely discernable circular feature, about 30 meters in radius, within which lies an area of chaotic terrain of indeterminate disposition. This circular feature is not inconsistent with a small fence, such as might be used to discourage access to a radiologically hazardous area following an underground nuclear tests, and it is vaguely suggestive of the ring of a small subsidence crater.

The February 2000 IKONOS imagery of Site A is not inconsistent with the use of this site for one of the May 1998 underground nuclear tests. There are, however, no features evident in the IKONOS imagery that would conclusively associate this site with an underground nuclear test. Perhaps of greater importance, there are no features evident at this site that can be associated with any of the ground-truth photographs released by the Government of India.

A single aerial image of this site, released by the Bhabha Atomic Research Centre, and another aerial view broadcast by CNN, provide a broader perspective on this area which provides clear correlation with the pre-shot satellite imagery. These two photographs disclose that the small subsidence crater from the test was centered on a long shed [#1], and that a pair of parallel sheds {#2 & #3] ran at right angles to this shed. A fourth shed [#4] can be seen in the background.

| Satellite Imagery of Khetolai Site-A

|

|

Khetolai - Site A SPIN-2 IMAGERY 01 June 1996 |

Khetolai - Site A IKONOS IMAGERY 03 February 2000 |

Gupta and Pabian identified the area they designated as Site C as a possible underground nuclear test site. As with Site A, Site C is surrounded by multiple layers of perimeter barriers, and had other features that fit the profile of a underground nuclear test shaft location.

A comparison of the 1996 pre-test SPIN-2 imagery and the 2000 post-test IKONOS imagery discloses essentially no changes in the appearance of this site, apart from minor discrepancies in vegetation cover. There are no features that can be associated with any of the nuclear test ground-truth photographs published by the Government of India, and no alterations in the appearance of this site that might be hypothesized to have resulted from the conduct of an underground nuclear test.

| Satellite Imagery of Khetolai Site-C

|

|

Khetolai - Site C SPIN-2 IMAGERY 01 June 1996 |

Khetolai - Site C IKONOS IMAGERY 03 February 2000 |

An examination of SPIN-2 and IKONOS imagery of the central part of the Khetolai military range, and the immediate surrounding area, disclose no other features that are consistent either with ground truth photographs of the May 1998 tests released by the Government of India, or with features that might be readily associated with multi-kiloton underground nuclear tests.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|