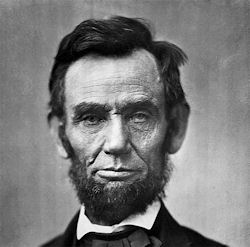

Abraham Lincoln (1861- April 1865)

Sixteenth President of the United States. Born in Harding County, Kentucky, Feb. 12, 1809. Died at Washington, D. C, April 15, 1865. Of Quaker descent. Farmer and surveyor. Practiced law in Springfield, 111., 1837. Captain in Black Hawk War 1832. Whig member Illinois Legislature 1834-42 and 1849. Republican candidate United States Senator 1858, opposing Stephen A. Douglas, denouncing slavery. Nominated President by the Republicans in 1860, and inaugurated President of the United States March 4, 1861, defeating John C Breckinridge of the Southern Democrats, and Stephen A. Douglas, candidate for the Northern Democrats, with Hannibal Hamlin as his Vice-President. He proclaimed a blockade of the Southern ports April 19, 1861. Opposed by Greeley.

Sixteenth President of the United States. Born in Harding County, Kentucky, Feb. 12, 1809. Died at Washington, D. C, April 15, 1865. Of Quaker descent. Farmer and surveyor. Practiced law in Springfield, 111., 1837. Captain in Black Hawk War 1832. Whig member Illinois Legislature 1834-42 and 1849. Republican candidate United States Senator 1858, opposing Stephen A. Douglas, denouncing slavery. Nominated President by the Republicans in 1860, and inaugurated President of the United States March 4, 1861, defeating John C Breckinridge of the Southern Democrats, and Stephen A. Douglas, candidate for the Northern Democrats, with Hannibal Hamlin as his Vice-President. He proclaimed a blockade of the Southern ports April 19, 1861. Opposed by Greeley.

War President (the Civil War, 1861-65), and through his skill gained victory over the Confederate States. In 1862 he issued a proclamation of emancipation of the Slaves. In 1864 he made U. S. Grant Commander-in-Chief of the Army. He was re-elected President of the United States 1864, with Andrew Johnson as Vice-Prsesident. Beginning his second term of office March 4, 1865, was occupied with plans for the reconstruction of the South, when he was shot at Ford's Theater, Washington, DC, by John Wilkes Booth, April 14, 1865. Buried Oak Ridge, Springfield, IL.

Abraham Lincoln, 16th president of the United States, was the first president born west of the Appalachian Mountains. His birth in a log cabin at Sinking Springs Farm took place on February 12, 1809, when that part of Kentucky was still a rugged frontier. When Abraham was two and a half his father moved his young family ten miles away to a farm on Knob Creek. The story of Lincoln's journey from log cabin to the White House that began here has long been a powerful symbol of the unlimited possibilities of American life.

Lincolnís father, Thomas, moved to Kentucky, then part of Virginia, with his parents about 1782, only seven years after Daniel Boone pioneered this uncharted region. By the time of his marriage to Nancy Hanks in 1806, he was a farmer and carpenter. In 1808, he purchased 300 acres near the Sinking Spring, one of the areaís numerous springs whose water dropped into a pit and disappeared into the earth. The soil was stony red and yellow clay, but the spring provided an important source of water. Only two years after he purchased it, Thomas Lincoln lost his land in a title dispute, which was not settled until 1816.

In 1811, the Lincolns leased 30 acres of a 230-acre farm in the Knob Creek Valley while waiting for the land dispute to be settled. The creek valley on this new farm contained some of the best farmland in Hardin County. A well-traveled road from Bardstown, Kentucky, to Nashville, Tennessee, ran through the property. Abraham Lincolnís first memories are from his time here, working alongside his father, playing with his sister, and assisting his adored mother. In the early years of his life, he learned from the self-sufficiency of pioneer farming and from short periods of schooling. His attendance at subscription schools lasted only a few months. Lincoln may have begun to form his views on slavery here. The Lincoln family belonged to an antislavery church.

Lincoln in southern Indiana for 14 years, growing from a boy to a young man. He used his hands and his back to help carve a farm and home out of the frontier forests. He used his mind to enter and explore the world of books and knowledge. He found adventure, but also knew deep personal loss with the death of his mother in 1818 and his sister ten years later. These experiences helped shape the character of the man who became one of Americaís most revered leaders.

In the winter of 1816, the Lincolns moved from Kentucky to a tiny settlement along Little Pigeon Creek. They spent the first, hard winter in a temporary shelter. The harvest was already over, so they lived off wild game, corn, and pork bartered from nearby settlers. The next year, aided by neighbors, Thomas Lincoln built a more suitable log house for the family of four: his wife Nancy, and their children, Sarah, nine, and Abe, seven. The slow and painstaking task of converting the surrounding forest to farmland soon changed from hopeful to tragic. In October of 1818, Nancy Hanks Lincoln fell ill with milk sickness and died within a few days. Milk sickness was a common and often fatal illness brought on by consuming milk or meat from an animal that had eaten snakeroot, a poisonous plant that thrived in the harsh environment. They buried her on a gentle knoll between a quarter and a half-mile from the home.

He grew tall and strong, eventually reaching 6í4Ē. He helped his father farm their land and did odd jobs for neighbors. He gained a reputation for his superb skill with an ax. He soon showed a driving ambition to better himself and to escape the hardships of frontier life. Although he received limited formal schooling, perhaps totaling one year in his entire youth, young Abraham devoured as many books as he could find. With his ready wit, inquiring mind, and gift for oratory, he became a master of crossroadsí debate. His neighbors reported that his two favorite tools were a book and an axe.

Lincoln came to Illinois with his family in 1830. He moved to New Salem a year later, pursuing various attempts as a merchant, beginning his legal studies in earnest, and involving himself in local politics. In 1832, he ran unsuccessfully for the State legislature as a Whig. He was more successful two years later winning the seat he held until 1841. By March 1837, he gained admission to the Illinois Bar and soon moved to Springfield, with all his possessions in two saddlebags. Springfield became the Illinois State capital in 1839, and Lincolnís career as a legislator and attorney prospered. In 1842, the year he left the legislature, he began to court socially prominent Mary Todd. Her family opposed the young couple's match until the day of their wedding, November 4, 1842.

For the first year and half, the newlyweds lived in rented rooms, where their first son Robert Todd was born. In 1844, Lincoln purchased the only home he ever owned for $1,500. Built in 1839, the house was originally a one-story cottage with two attic rooms. Here Mrs. Lincoln gave birth to three more sons, Edward, William, and Thomas. Edward died in the back parlor in 1850; Robert Todd Lincoln was the only son who lived to adulthood. Between 1846 and 1855, Lincoln enlarged the house to 12 rooms and two full stories.

Retired from the State legislature and with a thriving law practice, Lincoln achieved his first major political triumph when he won election to the United States House of Representatives in 1846. By the time he returned to Springfield the following October, between sessions of Congress, he had already decided not to make a bid for reelection. At the end of his term in the spring of 1849, discouraged with politics, he came back to Springfield and turned his attention to the law.

In 1854, the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which reopened the whole divisive question of the expansion of slavery into the territories, brought Lincoln back into the political forum. In 1855, he ran unsuccessfully for the United States Senate as a Whig. His decision to join the newly formed Republican Party in 1856 marked a turning point in his career. Lincoln rapidly rose to a position of leadership in the party. In 1858, the Illinois Republicans named him their candidate for the United States Senate, running against Stephen A. Douglas, the author of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Lincolnís acceptance speech, with its ringing prediction that ďa house divided cannot stand,Ē set the tone of the campaign. Lincolnís logic, moral fervor, elegant language, and skillful debating techniques gained him national attention. Douglas won the election, but Lincolnís status as a Westerner, an eloquent speaker, a skilled debater, and a moderate anti-slavery man won him the Republican nomination for president in 1860.

It has come to be a commonly accepted opinion that if the Republican convention of 1860 had not met in Chicago, it would have nominated Mr. Seward and not Mr. Lincoln. Seward was the acknowledged leader of the new party; had been its most telling spokesman; had given its tenets definition and currency. Lincoln had not been brought within view of the country as a whole until the other day, when he had given Douglas so hard a fight to keep his seat in the Senate, and had but just now given currency among thoughtful men to the striking phrases of the searching speeches he had made in debate with his practised antagonist. His managers saw to it that the galleries were properly filled with men who would cheer every mention of his name until the hall was shaken. Every influence of the place worked for him and he was chosen.

On May 17, 1860, Lincoln received a committee from the Republican Nominating Convention in the parlor of his house. They informed him of his nomination as the party's presidential candidate. He conducted the campaign from his residence. He entertained numerous visitors, but left the majority of traveling, speechmaking, and writing to others. Running against three opponents, he received a clear majority of the electoral votes, but only about 40 percent of the popular vote. Not a single Southern state voted for Lincoln, and within six weeks of his election, South Carolina seceded.

The Civil War began five weeks after Lincolnís inauguration in March 1861, with the shelling of the Federal garrison at Fort Sumter by the newly formed Confederacy. Blending principles and political skill, Lincoln provided strong wartime leadership for the North and assumed unprecedented presidential power. One of his first tasks was keeping several border States from seceding. Some people denounced the measures he took to silence critics of the war and Confederate sympathizers as unconstitutional, but he took the position that the national emergency justified his actions. Until he finally found an effective general in Ulysses S. Grant, he often participated directly in military decision making. He and his secretary of state succeeded in preventing international recognition for the Confederacy. His primary war aim was always the preservation of the Union.

Lincoln's penchant for appointing Democrats and incompetents to important positions in the Administration and commands in the military enraged his power base, the left wing of his Republican party. Though not unprecedented in Lincoln's time, or now, for a president to appoint people of varying political thought to positions in the Cabinet, Lincoln took the practice to a new and dangerous level.

For the North, the war produced a great hero in Abraham Lincoln ó a man eager, above all else, to weld the Union together again, not by force and repression but by warmth and generosity. In 1864 he had been elected for a second term as president, defeating his Democratic opponent, George McClellan, the general he had dismissed after Antietam. Lincolnís second inaugural address closed with these words: "With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nationís wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan ó to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations."

Three weeks later, two days after Leeís surrender, Lincoln delivered his last public address, in which he unfolded a generous reconstruction policy. On April 14, 1865, the president held what was to be his last Cabinet meeting. That evening with his wife and a young couple who were his guests ó he attended a performance at Fordís Theater. There, as he sat in the presidential box, he was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth, a Virginia actor embittered by the Southís defeat. Booth was killed in a shootout some days later in a barn in the Virginia countryside. His accomplices were captured and later executed.

Lincoln died in a downstairs bedroom of a house across the street from Fordís Theater on the morning of April 15. Poet James Russell Lowell wrote: "Never before that startled April morning did such multitudes of men shed tears for the death of one they had never seen, as if with him a friendly presence had been taken from their lives, leaving them colder and darker. Never was funeral panegyric so eloquent as the silent look of sympathy which strangers exchanged when they met that day. Their common manhood had lost a kinsman."

Lincolnís assassination in 1865 caused a national outpouring of grief, and his home became the focus for mourners. After a highly irregular military trial, four of the conspirators were found guilty and hanged; the sentences for the other four ranged from six years hard labor to life in prison. President Andrew Johnson pardoned the surviving conspirators in 1869.

If Lincoln was great in his life, he was, in one sense, fortunate in his death. For the assassination of the President followed closely on the surrender of Lee, and the same week saw the virtual conclusion of the war and the death of the ruler under whose auspices the end had come. History hardly affords a parallel to the circumstance. It is the lot of most public men to survive their reputation, and few are they who have had the fortune ó like Lincoln ó to be struck down in the hour of their victory.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|