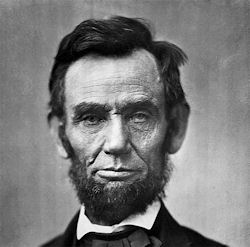

Abraham Lincoln - A Revisionist View

The mythological Abraham Lincoln is held up by both Democrats and Republicans alike. He is a beacon of freedom and a champion of racial equality. But Lincoln had long concluded that some system of gradual emancipation at national expense, coupled with an effort to colonize the freed people abroad provided the greatest promise of solving the slave issue. In 1854, Lincoln addressed his own solution to slavery at a speech delivered in Peoria, Illinois: “I should not know what to do as to the existing institution [of slavery]. My first impulse would be to free all the slaves, and send them to Liberia, to their own native land.” He suggested that there was "a moral fitness in returning to Africa her children whose ancestors have been torn away from her by the ruthless hand of fraud and violence." When the Africa option did not pan out he suggested that the slaves, when eventually freed, would be better off in a colony of their own in the Republic of New Granada.

The mythological Abraham Lincoln is held up by both Democrats and Republicans alike. He is a beacon of freedom and a champion of racial equality. But Lincoln had long concluded that some system of gradual emancipation at national expense, coupled with an effort to colonize the freed people abroad provided the greatest promise of solving the slave issue. In 1854, Lincoln addressed his own solution to slavery at a speech delivered in Peoria, Illinois: “I should not know what to do as to the existing institution [of slavery]. My first impulse would be to free all the slaves, and send them to Liberia, to their own native land.” He suggested that there was "a moral fitness in returning to Africa her children whose ancestors have been torn away from her by the ruthless hand of fraud and violence." When the Africa option did not pan out he suggested that the slaves, when eventually freed, would be better off in a colony of their own in the Republic of New Granada.

In the fall of 1858, Abraham Lincoln was running against Judge Stephen Douglas, as well as against the perception that he was in favor of freeing the slaves. Douglas was a virulent racist. So, in the first debate, towards the beginning of his remarks, he sought to assure the white voters of where he actually stood in regard to slavery and racial equality: “I will say here, while upon this subject, that I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so. I have no purpose to introduce political and social equality between the white and the black races. There is a physical difference between the two, which, in my judgment, will probably forever forbid their living together upon the footing of perfect equality, and inasmuch as it becomes a necessity that there must be a difference, I, as well as Judge Douglas, am in favor of the race to which I belong having the superior position.”

During his fourth debate with Stephen Douglas, Abraham Lincoln reiterated his stance on both slavery and race, almost verbatim: “I will say then that I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races, [applause]-that I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people; and I will say in addition to this that there is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality. And inasmuch as they cannot so live, while they do remain together there must be the position of superior and inferior, and I as much as any other man am in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race.”

When the Civil War began in 1861, Lincoln did not pursue abolishing slavery or incorporating Negro soldiers into the Union army. Lincoln was working hard to retain favor with the border states, but he also needed to balance the disquiet of the northern Copperhead interests with the beliefs of the fervent abolitionists.

In 1861, during his inauguration speech, Lincoln felt the need to once again reminded the nation as to where he stood on race and slavery. He reiterated his intention to not free the slaves in states where it already existed, and in regards to his thoughts on race, he referenced the country back to his speeches in the Douglas debates: “Apprehension seems to exist among the people of the Southern States that by the accession of a Republican Administration their property and their peace and personal security are to be endangered. There has never been any reasonable cause for such apprehension. Indeed, the most ample evidence to the contrary has all the while existed and been open to their inspection. It is found in nearly all the published speeches of him who now addresses you. I do but quote from one of those speeches when I declare that–I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.”

By early 1861, Lincoln ordered a secret trip to modern-day Panama to investigate the land of a Philadelphian named Ambrose Thompson. Thompson had volunteered his Chiriqui land as a refuge for freed slaves. The slaves would work in the abundant coal mines on his property, the coal would be sold to the Navy, and the profits would go to the freed slaves to further build up their new land. Lincoln sought to test the idea on the small slave population in Delaware, but the idea met fierce opposition from abolitionists when it went public.

In April 1862, Lincoln was still of the mind that emancipation and deportation was the key to a peaceful United States. He supported a bill in Congress that provided money “to be expended under the direction of the President of the United States, to aid in the colonization and settlement of such free persons of African descent now residing in said District, including those to be liberated by this act, as may desire to emigrate to the Republic of Haiti or Liberia, or such other country beyond the limits of the United States as the President may determine.”

In August of 1862, Lincoln invited five prominent black men to the White House, the first black delegation invited on such terms. The topic was simple, that white and blacks cannot coexist and that separation is the most expedient means to peace. Lincoln encouraged these five men to rally support for an exodus. In the August 14, 1862 meeting with a group of Negro freemen at the White House, Lincoln explained his position: "You and we are different races. We have between us a broader difference than exists between almost any other two races .... this physical difference is a great disadvantage to us both, as I think. Your race suffers very greatly, many of them, by living among us, while ours suffers from your presence. In a word, we suffer on each side... It is better for us both, therefore, to be separated."

On August 19, 1862, Horace Greeley, the Editor of the New York Tribune wrote a scathing Op-Ed calling for the immediate emancipation of the slaves. Lincoln responded on 22 August 1862: "I would save the Union. I would save it the shortest way under the Constitution. The sooner the national authority can be restored; the nearer the Union will be "the Union as it was." If there be those who would not save the Union, unless they could at the same time save slavery, I do not agree with them. If there be those who would not save the Union unless they could at the same time destroy slavery, I do not agree with them. My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that." Most of the war news during the summer of 1862 was bad, and he wanted to wait to make the announcement until after a Union victory. On September 17, Union forces turned back a Confederate invasion of the North at the decisive and bloody battle of Antietam. On September 22, while still living at the cottage, Lincoln published the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, announcing his intention of freeing all the slaves in the rebel states on January 1, 1863.

The tragedy of the conflict weighed heavily on Lincoln as the war raged on and the lists of casualties grew. He won reelection to a second term in 1864, as Union army victories suggested that the war might be nearing its end. Lincoln was already seeking ways to reconcile the North and South. His Second Inaugural Address looked forward to a moderate Reconstruction program, guided by the principle of “malice toward none, with charity for all.” Lincoln did not live to put these policies into effect.

Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to General Grant at Appomattox Courthouse on April 9, 1865, effectively ending four years of devastating warfare. President Lincoln proclaimed April 14 as a day of thanksgiving. To celebrate, he decided to attend a performance of a lighthearted comedy, Our American Cousin, at Ford’s Theatre.

Lincoln’s father, Thomas Lincoln, witnessed the murder of his own father, also named Abraham. One day in the spring of 1786, while Abraham Lincoln the elder worked in his Kentucky field with his three sons, a Native American attacked and shot him dead. The Indian prepared to abscond with young Thomas when Thomas’s older brother Mordecai shot the assailant from a distance and saved his brother’s life. Mordecai harbored a lifelong enmity toward Native Americans that “was ever with him like an avenging spirit.”

Lincoln’s acceptance of US Indian policy indicated he conformed to the general social attitudes toward Native Americans in his time. He continued to view them as a foreign people that would need to be removed through purchase or conquest. He saw Native Americans as a population to be conquered and applauded the efforts of those who contributed to the conquest. In Minnesota, the US Government had recently signed a treaty with the Dakota Sioux nation, and in the fall of 1862, after the United States failed to meet its treaty obligations with the Dakota people, several Dakota warriors raided an American settlement, killed some of the settlers and stole food. This began a short period of bloody conflict between some of the Dakota people, white settlers, and the U.S. Military. After little more than a month, several hundred of the Dakota warriors surrendered and the rest fled north to what is now Canada. Those who surrendered were quickly tried in military tribunals, and 303 of them were condemned to death. Ultimately, 39 Dakota men were sentenced to die. And on December 26, 1862, by order of President Lincoln, and with nearly 4,000 white American settlers looking on, the largest mass execution in the history of the United States took place.

Under President Abraham Lincoln, the Sand Creek massacre occurred in 1864 when the U.S. Army attacked the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes unprovoked, killing about 250 Native Americans. Despite assurance from American negotiators that they would be safe, and despite Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle raising both a United States flag and a white flag as symbols of peace, Colonel John Chivington ordered his troops to take no prisoners and to pillage and set the village ablaze, violently forcing the ambushed and outnumbered Cheyenne and Arapaho villagers to flee on foot. Colonel Chivington and his troops paraded mutilated body parts of men, women, and children in downtown Denver, Colorado, in celebration of the massacre.

Lincoln created the Montana Territory on May 26, 1864. Numerous Native American tribes lived in the vast area of what we now call Montana: the Crow, Cheyenne, Blackfoot, Flathead, and more. Meriwether Lewis and William Clark were the first white explorers to document their journey through the lands of the Louisiana Purchase, but more settlers followed. Combat between U.S. military and Native Americans defending their land became frequent. Perhaps the most famous of these battles occurred in Montana on June 25, 1876, when the Dakota (Sioux) and Cheyenne defeated General George Custer's regular army during the Battle of the Little Bighorn, also known as Custer's Last Stand.

Lincoln also sought to put an end to the Indian wars being fought in the Southwest against the Navajo and the Pueblos. The military offensive against our tribes by the US Army intensified with the start of the Civil War in 1861 and steadily increased thereafter. In the fall of 1863, General Carleton of the US Army, the army of which Abraham Lincoln was the commander in chief, gave the following order to US Army Officer, Kit Carson, who had been brought into the Indian War Campaigns for the express purpose of removing the Navajo and Pueblo people to Brosque Redondo. Every Navajo male was to be killed or taken prisoner on sight. Ultimately over 8,000 Navajo people were rounded up by President Lincoln’s army, and marched from Fort Wingate to Bosque Redondo in what is known as “The Long Walk.”

Four days before his death, speaking to Gen. Benjamin Butler, Lincoln still pressed on with deportation as the only peaceable solution to America’s race problem. “I can hardly believe that the South and North can live in peace, unless we can get rid of the negroes … I believe that it would be better to export them all to some fertile country…”

In 1968, the African-American Magazine Ebony asked the question, “Was Abe Lincoln a White Supremacist?” The article sought to dismantle the “mythology of the Great Emancipator” going on to say that Lincoln “shared the racial prejudices of most of his white contemporaries.” The article concluded that “no other American story is so false” as the one depicting Lincoln as the embodiment of enlightened white moral leadership. Lerone Bennett Jr.‘s article caused considerable controversy in academic circles and among general readers. In 2000, Bennett published the book Forced Into Glory: Abraham Lincoln’s White Dream, which expounded upon questions and themes raised by the earlier article. Lerone Bennett Jr. was the executive editor emeritus of Ebony magazine.

Beginning with the argument that the Emancipation Proclamation did not actually free African American slaves, this dissenting view of Lincoln's greatness surveys the president's policies, speeches, and private utterances and concludes that he had little real interest in abolition. On January 1, 1863, the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect. But, if you look closely, this proclamation did not free all the slaves. The wording of the Emancipation Proclamation was extremely specific, and limited the locations from which slaves were to be freed. The Emancipation Proclamation exempted many areas and counties throughout the southern slave-owning states, and never even mentioned freeing slaves from the northern states where slavery was legal (Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware).

Pointing to Lincoln's support for the fugitive slave laws, his friendship with slave-owning senator Henry Clay, and conversations in which he entertained the idea of deporting slaves in order to create an all-white nation, the book, concludes that the president was a racist at heart—and that the tragedies of Reconstruction and the Jim Crow era were the legacy of his shallow moral vision.

Abe never had a change-of-heart epiphany; was pushed to do the right thing only by others--the abolitionists and a radical anti-slavery Republican Congress; and to the end of his life sympathized not with blacks but with the tragedy of the white slave-owners stripped of their property and burdened with a harder life. Lincoln's solution to it all was very gradual emancipation, with compensation to the slave-owners and expatriation of the freed blacks to their homeland--Africa.

In a New York Times review, renowned Lincoln historian James McPherson noted Forced into Glory's tendency to distort sources or misleadingly omit essential parts of them. Other top Lincoln historians have warned about similar problems. Eric Foner called the book a "one-dimensional" portrayal. Allen Guelzo called it an "infamous screed." George Fredrickson said the book was extreme and driven by ideology.

Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles’ diary entry for September 26, 1862. That entry notes that Attorney General Edward Bates at a cabinet meeting (which took place a day after the issuance of the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation) supported compulsory deportation of blacks, but “the President," Welles wrote, "objected unequivocally to compulsion. Their emigration must be voluntary and without expense to themselves”.

George Fredrickson's "Big Enough to Be Inconsistent: Abraham Lincoln Confronts Slavery and Race" puts Lincoln's views and actions on race and emancipation in the least complimentary light. Lincoln’s antislavery convictions, however genuine and strong, were held in check by an equally strong commitment to the rights of the states and the limitations of federal power. Lincoln’s beliefs about racial equality in civil rights, stirred and strengthened by the African American contribution to the northern war effort, were countered by his conservative constitutional philosophy, which left this matter to the states. “Cruel, merciful; peace-loving, a fighter; despising Negroes and letting them fight and vote; protecting slavery and freeing slaves.” Abraham Lincoln was, W.E.B.Du Bois declared, “big enough to be inconsistent.”

When he was asked during an electoral campaign whether he was advocating for “negro equality,” Lincoln put the matter to rest. “I will say then that I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races,” said Lincoln to applause. He added, finally, “I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people; and I will say in addition to this that there is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality.”

Malcolm X, the famous African-American vernacular intellectual, said that Lincoln “probably did more to trick Negroes than any other man in history...he wasn't interested in freeing the slaves. He was interested in saving the Union.”

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|