Gerrymander

US Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment, Section 1, [the "equal protecton clause"] states : "All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws."

US Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment, Section 1, [the "equal protecton clause"] states : "All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws."

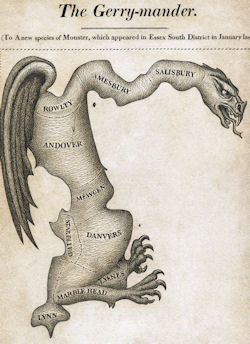

“Gerrymandering” was named for Elbridge Gerry, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. Gerry remained on the scene in the early days of the republic. In addition to signing the Declaration, he also signed the Articles of Confederation. as a member of the First Congress (1789–1791), Gerry backed James Madison’s proposals for Constitutional amendments that eventually became the Bill of Rights, the first 10 amendments to the Constitution.

Gerry retired from public life after two terms in the House, but it was an active retirement. As Governor of Massachusetts (1810–1812), Gerry approved a redistricting plan for the state senate that gave the political advantage to Republicans. Someone observed that one of the districts looked like a salamander, and soon the process was known as “gerrymandering.” Since then, “gerrymandering” has for years produced odd-shaped congressional and state legislative districts. He served not only as Massachusetts Governor but also as President Madison’s Vice President (1813–1814). He died while Vice President in 1814.

Partisan gerrymandering is a widespread practice in U.S. congressional redistricting, particularly in states where the legislature controls the process. Recent examples in states like Texas and Missouri show Republicans redrawing maps to secure control of the U.S. House, while Democrats attempt to counter this in other states. Racial gerrymandering, the manipulation of district lines to dilute the voting power of minority groups, is a long-standing issue. However, this practice is complicated by recent Supreme Court cases that require plaintiffs to prove racial intent separate from partisan considerations, which is extremely difficult to do.

Partisan political gerrymandering, the drawing of legislative district lines to subordinate adherents of one political party and entrench a rival party in power, is an issue that has vexed the federal courts for more than three decades. Prior to the 1960s, the Supreme Court had determined that challenges to redistricting plans presented nonjusticiable political questions that were most appropriately addressed by the political branches of government, not the judiciary. In 1962, the Supreme Court held in the landmark ruling of Baker v. Carr that a constitutional challenge to a redistricting plan is justiciable, identifying factors for determining when a case presents a nonjusticiable political question, including a lack of [a] judicially discoverable and manageable standard[ ] for resolving it. In the years that followed, while invalidating redistricting maps on equal protection grounds for other reasons—inequality of population among districts or racial gerrymanding — the Court did not nullify a map based on a determination of partisan gerrymandering.

In the 1986 case of Davis v. Bandemer, the Court ruled that partisan gerrymandering in state legislative redistricting is justiciable under the Equal Protection Clause. Although the vote was 6-3 in favor of justiciability, a majority of the Justices could not agree on the proper test for determining whether the particular gerrymandering in this case was unconstitutional and reversed the lower court’s holding of unconstitutionality by a vote of 7-2. Hence, as a result of Bandemer, the Court left open the possibility that claims of unconstitutional partisan gerrymandering could be judicially reviewable, but did not ascertain a discernible and manageable standard for adjudicating such claims.

Similarly, following Bandemer, the Supreme Court could not reach a consensus for several years on the proper test for adjudicating claims of unconstitutional partisan gerrymandering. First, in the 2004 ruling, Vieth v. Jubelirer, a four-Justice plurality would have overturned Bandemer to hold that political gerrymandering claims are nonjusticiable. Justice Anthony Kennedy, casting the deciding vote and concurring in the Court’s judgment, agreed that the challengers before the Court had not yet articulated comprehensive and neutral principles for drawing electoral boundaries or any rules that would properly limit and confine judicial intervention. Nonetheless, Justice Anthony Kennedy held out hope that in some future case, the Court could find some limited and precise rationale to adjudicate other partisan gerrymandering claims, thereby leaving Bandemer intact.13 In 2006, in League of United Latin American Citizens v. Perry, a splintered Court again failed to adopt a standard for adjudicating political gerrymandering claims, but did not overrule Bandemer by deciding such claims were nonjusticiable. Likewise, in 2018, the Court considered claims of partisan gerrymandering, but ultimately issued narrow rulings on procedural grounds specific to those cases.

Ultimately, in the 2019 case, Rucho v. Common Cause, the Supreme Court held that there were no judicially discernible and manageable standards by which courts could adjudicate claims of unconstitutional partisan gerrymandering, thereby implicitly overruling Bandemer. According to the Court, the federal courts are not equipped to apportion political power as a matter of fairness and it is not even clear what fairness looks like in this context. As a result of Rucho, claims of unconstitutional partisan gerrymandering are not subject to federal court review because they present nonjusticiable political questions. Writing for the Court, Chief Justice John Roberts acknowledged that excessive partisan gerrymandering reasonably seem[s] unjust, stressing that the ruling does not condone it, but reiterated that the Framers gave Congress the power to do something about partisan gerrymandering in the Elections Clause.

Japan's electoral system for its legislative body, the Diet, addresses gerrymandering but struggles with malapportionment. Non-partisan commission: A non-partisan commission is responsible for drawing electoral districts. This structure effectively prevents the overt partisan gerrymandering seen in the US. The primary issue is malapportionment, the imbalance of voting power between districts. Underrepresented urban areas have smaller vote values than overrepresented rural districts. This disparity is so significant that Japan's High Courts have repeatedly ruled it to be "in a state of unconstitutionality," though they have refrained from nullifying election results. Based on population shifts recorded in the 2020 national census, the country reallocated 10 seats, shifting representation from less-populated rural areas to growing urban ones. This process, known as "Increase 10, Decrease 10," resulted in significant feuds within political parties, particularly the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), as incumbents vied for single-member districts. A new phenomenon is states redrawing maps between the decennial census, driven by political maneuvering. Multiple states are considering or pursuing redistricting ahead of the 2026 elections.

Following calls from President Trump, Republican-controlled legislatures in states like Texas, Missouri, and North Carolina are aggressively redrawing maps to create more Republican-leaning seats. Florida, Indiana, and Ohio are also exploring these options. The Texas redistricting alone could add five more Republican seats to the House.

In response, Democrats in states like California, Maryland, and Illinois have raised the possibility of their own mid-decade gerrymanders. California is putting a proposition on the ballot for voters to approve a new map that could offset the Republican gains in Texas. Legal obstacles: Many Democratic efforts are constrained by state laws and constitutions, making it difficult for them to respond in kind.

The US Supreme Court heard oral arguments in October 2025 for a case (Louisiana v. Callais) that could weaken or even strike down Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. This provision prohibits racial discrimination in voting practices, including protecting the ability of minority groups to elect their preferred candidates. A decision against the Voting Rights Act could allow Republican-controlled states, particularly in the South, to dismantle majority-minority districts. This could net Republicans up to 19 more House seats and potentially secure control of the House for years to come.

The current wave of redistricting and potential legal changes create a favorable environment for Republicans to solidify their power and maintain control of the House. A gerrymandering "arms race" that Democrats are less able to win makes their path to reclaiming the House majority in 2026 more difficult. Experts warn that this surge in gerrymandering is a significant departure from democratic values and could undermine voter confidence.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|