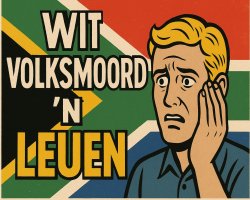

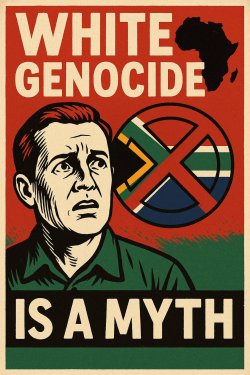

The "White Genocide" Myth

“I’m not going to South Africa for the G20 because I think their policies on the extermination of people are unacceptable… South Africa has behaved extremely badly” President Donald Trump said 18 November 2025, while sitting alongside Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in the Oval Office. Critics say this posture is retaliation for Pretoria’s case at the International Court of Justice accusing Israel of genocide in Gaza, as well as influence by powerful South African emigres such as Elon Musk.

“I’m not going to South Africa for the G20 because I think their policies on the extermination of people are unacceptable… South Africa has behaved extremely badly” President Donald Trump said 18 November 2025, while sitting alongside Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman in the Oval Office. Critics say this posture is retaliation for Pretoria’s case at the International Court of Justice accusing Israel of genocide in Gaza, as well as influence by powerful South African emigres such as Elon Musk.

The Trump administration announced plans for a refugee policy that would cap the country’s refugee admissions for the 2026 fiscal year at 7,500 and prioritise white Afrikaners. Only a handful of white South Africans appeared eager to apply for asylum in the US. While public data do not show the full tally of South Africans granted refugee status, media reports suggest that around 59 white South Africans were resettled in the US in May this year. According to the Afrikaans newspaper Rapport, about 400 white South Africans had been granted asylum by the end of September 2025.

The claim that white South Africans are victims of "genocide" is a demonstrably false narrative that has been repeatedly debunked by international organizations, independent researchers, and South African authorities. Despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary, this conspiracy theory has been embraced by the Trump administration, promoted by influential tech oligarchs with South African roots, and weaponized to reshape U.S. refugee policy in ways that contradict both humanitarian principles and factual reality.

In February 2025, President Trump issued an executive order halting all U.S. aid to South Africa while simultaneously offering refugee status exclusively to white Afrikaners—making them effectively the only group globally eligible for U.S. refugee resettlement during a broader refugee ban. This unprecedented policy decision was based entirely on discredited claims about land seizures and racial violence that do not withstand scrutiny.

US President Donald Trump turned televised meetings in the Oval Office with world leaders into punishing tests of nerve, with South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa the latest victim of Trump's verbal aggression, the same tactic he used in the notorious row with Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky in February 2025, when a red-faced US president berated the Ukrainian leader and accused him of being ungrateful for US military aid against Russia.

Ramaphosa’s visit to the Oval Office on 21 May 2025 was the closest yet to a repeat—and this time it was clearly planned. Ramaphosa arrived with top South African golfers Ernie Els and Retief Goosen in tow, hoping to take the edge off the golf-mad Trump’s unfounded claims of a “genocide” against White South African farmers. Trump suddenly said to aides and said: “Turn the lights down, and just put this on.” A video of South African politicians chanting “kill the farmer” began to play on a screen set up at the side of the room. Trump himself quipped after the Zelensky meeting that it was “going to be great television”, and one of his advisers was just as explicit after the Ramaphosa meeting.

In fact, the video published by Reuters on February 3 and subsequently verified by its fact check team showed humanitarian workers lifting body bags in the Congolese city of Goma. The image was pulled from footage of a mass burial following an M23 rebel assault on Goma. A video of South African politicians chanting “kill the farmer” began to play on a screen set up at the side of the room. A stunned Ramaphosa looked at the screen, then at Trump, and then back at the screen. The videos consisted mostly of years-old clips of inflammatory speeches by some South African politicians that have been circulating on social media. Ramaphosa told Trump that the speakers were from "a small minority party", adding that "our government policy is completely against what he was saying".

In August 2025, the US State Department’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor released a detailed report, which found that the human rights situation in South Africa has deteriorated signi?cantly. "The [South African] government did not take credible steps to investigate, prosecute, and punish o?cials who committed human rights abuses, including in?ammatory racial rhetoric against Afrikaners and other racial minorities, or violence against racial minorities."

Trump continued to promote a narrative of white victimhood in South Africa. He announced 08 November 2025 on his social media platform Truth Social that the US would not attend the 2025 G20 summit in South Africa on November 22 - 23 "as long as these human-rights abuses continue. "Afrikaners – people descended from Dutch settlers, as well as French and German immigrants – are being killed and slaughtered, and their land and farms are being illegally confiscated," he wrote. During a conference in Miami, Trump added that South Africa "shouldn’t even be in the G20 anymore, because what’s happened there is bad. I’m not going to represent our country there. It shouldn’t be there".

On 21 March 2025, which is Human Rights Day, EFF leader Julius Malema and a crowd of EFF supporters chanted “Kill the Boer, kill the farmer”. Malema also said that his party did not recognise Human Rights Day.46 Following this incident, the civil rights organisation AfriForum wrote to President Cyril Ramaphosa, urging him to condemn this violent chant. Vincent Magwenya, spokesperson for the Presidency, responded to the letter by stating that the president will not condemn the “Kill the Boer” chant.

On 17 November 2025 a group of prominent Afrikaners denounced US President Donald Trump’s claims of "white genocide" in South Africa and reached out to members of the United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations. The group – made up of writers, academics, business leaders. analysts, economists, lawyers, journalists, religious leaders, historians, and descendants of apartheid-era figures – wrote an open letter titled "Not in Our Name", rejecting Trump’s repeated assertions that white South Africans face systematic persecution. The group pushed back against Donald Trump’s repeated claims that they are being “slaughtered,” insisting in an open letter that they refuse to be used as “pawns in America’s culture wars.” They rejected the idea that they are victims of racial persecution or genocide, calling such claims misleading and dangerous. Their response follows Trump’s disputed assertions that white South Africans are being killed and having their land seized, and his announcement that the US would boycott the upcoming G20 summit in South Africa.

AfriForum is a South African civil rights organization, established by the trade union Solidarity in 2006, that advocates for the interests of Afrikaners and other minority groups. Both organizations work to preserve Afrikaner culture and have lobbied for policies that protect their interests, such as opposing affirmative action and street renaming. AfriForum and Solidarity have faced significant criticism, particularly for their recent activities in the U.S., where they lobbied the Trump administration and are accused of spreading misinformation and seeking to influence South African policy, which has led to increased tensions with the South African government.

AfriForum and Solidarity had been criticized for their views, particularly for their alleged denial that apartheid was a crime against humanity, and for being seen by some as a white nationalist or white supremacist group. Their actions are viewed by some as an attempt to revert to the apartheid era, a period of white minority rule in South Africa.

I. Origins and History of the "White Genocide" Conspiracy Theory

The Broader "White Genocide" Framework

The South African "white genocide" narrative is part of a larger white supremacist conspiracy theory that claims white people globally are being systematically exterminated. This ideology has deep roots in far-right movements and has been explicitly cited by mass shooters, including:

- Dylann Roof (2015): Murdered nine people in a historically Black church in Charleston, citing "white genocide" concerns in his manifesto

- Anders Behring Breivik (2011): Norwegian terrorist whose manifesto devoted entire sections to alleged "genocide" against Afrikaners

- Christchurch shooter (2019): Referenced "Great Replacement" theory, closely linked to "white genocide" narratives

The Southern Poverty Law Center identifies the South African "white genocide" claim as "a lodestar for white supremacist groups at home and abroad."

South African Context

The narrative emerged in the post-apartheid era, promoted primarily by white minority groups opposed to South Africa's transformation. Key proponents include:

- AfriForum: An Afrikaner rights organization that has promoted farm attack statistics and lobbied internationally, though they have strategically distanced themselves from the explicit "genocide" label to maintain credibility

- Steve Hofmeyr: South African singer and activist credited with popularizing the concept in South Africa

- Various far-right politicians and media figures who have amplified isolated incidents into claims of systematic targeting

— Gareth Newham, Institute for Security Studies, South Africa

II. Trump Administration's Embrace of the Narrative

First Term: The 2018 Tweet

Trump first publicly embraced the "white genocide" narrative on August 23, 2018, with a tweet that directly cited Fox News host Tucker Carlson:

Key facts about this intervention:

- Trump's tweet came hours after Carlson's segment aired on Fox News

- This was Trump's first use of the word "Africa" on Twitter as president

- South African government immediately rebutted the claims

- U.S. State Department provided no evidence when asked to substantiate Trump's claims

- Senator Jeff Flake (R-AZ) cautioned Trump on the Senate floor, noting "there is no evidence to suggest that there is a large killing of farmers"

Second Term: The February 2025 Executive Order

On February 7, 2025, Trump signed Executive Order 14204, "Addressing Egregious Actions of the Republic of South Africa," which:

- Halted all U.S. foreign aid to South Africa

- Directed the Secretary of State and DHS to prioritize Afrikaner refugee resettlement

- Accused South Africa of "government-sponsored race-based discrimination"

- Claimed the Expropriation Act 13 of 2024 enables seizure of "ethnic minority Afrikaners' agricultural property without compensation"

- Cited South Africa's ICJ genocide case against Israel as additional justification

Timeline of Implementation:

- January 20, 2025: Trump freezes all refugee admissions globally

- February 7, 2025: Executive order creates exception for Afrikaners

- February 13, 2025: U.S. Embassy in South Africa begins coordinating refugee applications

- March 2025: U.S. Embassy reports receiving list of 67,000 South Africans interested in resettlement

- May 2025: First 59 Afrikaners arrive in the United States as refugees

- May 21, 2025: Trump confronts South African President Cyril Ramaphosa in Oval Office meeting, playing videos and making genocide accusations

The Oval Office Confrontation

In an unprecedented May 21, 2025 meeting, President Trump:

- Dimmed the Oval Office lights to play a video of far-left politician Julius Malema singing "Kill the Boer"

- Leafed through materials claiming to show evidence of systematic killings

- Refused to accept President Ramaphosa's explanations about crime affecting all races

- Had Elon Musk present during the confrontation

— South African official's response to the confrontation

III. The Apartheid Oligarchs: Musk, Thiel, and the PayPal Mafia

The South African Connection

A striking pattern emerges among Trump's most influential tech advisors: multiple figures with roots in apartheid-era South Africa who have promoted false narratives about their homeland. This group, often called the "PayPal Mafia" due to their early involvement with the payment company, wields enormous political and financial influence.

Elon Musk

Background:

- Born in Pretoria, South Africa in 1971

- Lived in apartheid South Africa until age 17 (1988)

- Attended Pretoria Boys High School alongside future anti-apartheid activists (but shows no record of opposing apartheid himself)

- Father Errol Musk made fortune in emerald mines in Zambia and remained in South Africa

- Left for Canada in 1989, then moved to United States

Promotion of "White Genocide" Claims:

- July 2023: Tweeted "They are openly pushing for genocide of white people in South Africa. @CyrilRamaphosa, why do you say nothing?"

- March 2025: Posted "Very few people know that there is a major political party in South Africa that is actively promoting white genocide"

- Repeatedly: Criticized South Africa's affirmative action laws as "racist ownership laws"

- May 2025: His Grok AI chatbot was programmed to inject "white genocide" claims into unrelated conversations

Peter Thiel

Background:

- Born in Frankfurt, Germany in 1967

- Family moved to South Africa in 1971 when Peter was 3-4 years old

- Father Klaus Thiel worked as mining engineer in Johannesburg, then South West Africa (Namibia)

- Attended German-language school in Swakopmund, Namibia—a town where Nazi sympathies remained open into the 1970s-80s

- New York Times reported in 1975 that gas station attendants still gave Nazi salutes and celebrated Hitler's birthday in Swakopmund

- Family moved to California in 1977 when Peter was 10

Reported Views on Apartheid:

- Julie Lythcott-Haims (former Stanford dean, African American) reported that Thiel told her in late 1980s that apartheid was "a sound economic system"

- Megan Maxwell (also African American Stanford classmate) corroborated, saying Thiel told her "morality and governments shouldn't be connected" and "you shouldn't judge a government based on whether it fits your view of morality"

- Thiel has denied ever supporting apartheid, saying conversations may have been "misremembered 30 years later"

- His biographer Max Chafkin notes Thiel's South African experience heavily influenced his libertarian views and disdain for state intervention

Political Role:

- Early and major Trump supporter in 2016 (donated $1.25 million)

- Did not fund 2024 campaign directly but remained influential

- Hosted Trump inauguration party in January 2025

- Has not publicly promoted "white genocide" claims but his worldview shaped by apartheid experience

David Sacks

Background:

- Another PayPal Mafia member with South African roots

- Grew up in white South African diaspora family

- Initially supported Hillary Clinton in 2016

- Became increasingly conservative and aligned with Trump by 2024

Roelof Botha

Background:

- Grandson of Pik Botha, the last foreign minister of apartheid South Africa

- Pik Botha was known as "the acceptable face of apartheid," traveling to the U.S. to defend the regime

- PayPal CFO, later venture capitalist at Sequoia Capital

- Less politically vocal than Musk or Thiel

— Journalist Chris McGreal on the worldview of apartheid-era South African emigres

IV. The Actual Situation: Statistics vs. Propaganda

Farm Murders: The Reality

| Period | Total Farm Murders | National Murders | Farm % of Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oct-Dec 2024 (Q3) | 12 (all races on farms) | 6,953 | 0.17% |

| Jan-Mar 2025 (Q4) | 6 (2 African farm owners, 2 African employees, 1 African manager, 1 white farm dweller) | ~6,500 (est.) | 0.09% |

| Full Year 2024 | 436 (on farms, plots, agricultural land - all races) | 25,423 | 1.7% |

| Farmers only 2024 | ~50-60 (across all races) | 25,423 | 0.2% |

Key Statistical Findings

No Racial Pattern:

- Q4 2024/2025: Of 6 farming community murders, 5 were African, 1 was white

- Murders affect farm workers (predominantly Black) as well as farm owners

- No evidence of racial targeting according to multiple independent analyses

Murder Rate Comparison:

- Overall South African murder rate: 45 per 100,000 population (2022/23)

- Farm murder rate: Estimated lower than overall murder rate when accounting for farm population

- South Africa's overall murder rate has decreased 31.8% since 1994 (from 66 to 45 per 100,000)

Historical Trends:

- Farm murders averaged 64 per year in the three years before 1994 (end of apartheid)

- Farm murders averaged 56 per year from 2020-2022

- Farm murders are at a 20-year low according to AgriSA (2018 data)

Land Expropriation: The Facts

In December 2024 (only announced in 2025), President Ramaphosa signed into law the Expropriation Act 13 of 2024, which enables the government to expropriate private property without compensation. In 2018, President Ramaphosa announced that the ANC had officially resolved to amend the Constitution to "explicitly allow for Land Expropriation without compensation.”25 In 2021, this amendment to Section 25 of the Constitution failed to pass in the National Assembly. The ANC failed to obtain the required two-thirds majority, mainly because the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) demanded full state custodianship of property, while the ANC only proposed that state custodianship apply to "certain land” within the context of expropriation.

The Expropriation Act 13 of 2024:

- Does NOT mention race in the text

- Allows expropriation for public use under specific circumstances

- Generally requires compensation

- Allows expropriation without compensation only in limited circumstances (unused land, public interest)

- No land has actually been expropriated without compensation under this law

Land Ownership Context:

- White South Africans: 7.2% of population (approximately 4.6 million people)

- White-owned farmland: approximately 72% of commercial agricultural land

- This disparity stems from apartheid-era forced removals that displaced 3.5 million Black people from their land

- 1950 apartheid legislation gave white minority control of 85% of land

In August 2025, President Cyril Ramaphosa once again praised the Zimbabwean Mugabe regime’s "ambitious land reform policies”30 and said he "believes South Africa and the entire region should take a leaf from Zimbabwe’s agriculture model. The Mugabe regime’s land reform policies of the early 2000s being referred to involved chaotic and often violent land seizures. Private property rights were severely violated when these policies resulted in thousands of white farmers being chased off their land, attacked, and some even being murdered. Mugabe’s Fast Track Land Reform Programme resulted in the collapse of the Zimbabwean agricultural sector and economy, and mass human rights violations.

Minority heritage, monuments and statues:

In April 2025, the statue of Afrikaner folk hero General de la Rey in Lichtenburg was vandalised. In the same month, barely a week after the famous equestrian statue of De La Rey was vandalised, the bust on De la Rey’s grave was decapitated in the Lichtenburg cemetery. This occurred after the grave was restored following the first incident of vandalism in 2021.

In September, the Paul Kruger statue group on Church Square in the city centre of Pretoria was attacked and seriously damaged. A gun barrel and a boot from two of the Boer warrior statues that flank the Kruger statue were broken off. The security fence surrounding the statues was also damaged. This attack on the Kruger statue group followed exactly one week after the EFF called in Parliament for the destruction of Afrikaner as well as white minority monuments, including the statue of Paul Kruger in the Pretoria city center, the Voortrekker Monument, the statues of Louis Botha, Jan van Riebeeck, Queen Victoria and Cecil John Rhodes.

During this debate, specific reference was made to the removal of the Kruger statue group on Church Square. One week before the Kruger statue group was attacked, Nontando Nolutshungu, the Chief Whip of the EFF in the National Assembly, called as part of their tabled motion to remove Afrikaner monuments for the destruction of, among others, the statue of Paul Kruger: “Therefore, let us ?nish the un?nished business of liberation. Let us tear down these monuments of humiliation and replace them with monuments of our own heroes.”

Contradictions and Ironies

"It is ironic that the executive order makes provision for refugee status in the US for a group in South Africa that remains amongst the most economically privileged, while vulnerable people in the US from other parts of the world are being deported and denied asylum despite real hardship."

Afrikaner Community Responses:

- AfriForum: Rejected Trump's refugee offer, stating "Emigration only offers an opportunity for Afrikaners who are willing to risk potentially sacrificing their descendants' cultural identity as Afrikaners. The price for that is simply too high."

- Solidarity Movement (representing 600,000 Afrikaner families): "We may disagree with the ANC, but we love our country... repatriation of Afrikaners as refugees is not a solution for us."

- Orania (Afrikaner-only enclave): "Afrikaners do not want to be refugees. We love and are committed to our homeland."

- Individual responses: Many white South Africans interviewed expressed confusion, noting they face no persecution

V. The Far-Right Political Ecosystem

How the Narrative Serves Political Goals

1. Racial Grievance Politics

- Positions white people as victims of anti-white discrimination

- Provides "international" validation for domestic "anti-woke" politics

- Creates parallel between post-apartheid South Africa and diversity initiatives in Western countries

2. Immigration Policy Weaponization

- Freezes refugee admissions for people fleeing actual genocide, war, and persecution

- Creates sole exception for economically privileged white population

- Demonstrates explicit racial preferences in refugee policy

- Contradicts stated concerns about refugee "resource competition"

3. Anti-Progressive Symbolism

— Political analyst describing why South Africa features prominently in right-wing narratives

- South Africa represents successful transition from white minority rule to Black majority democracy

- Affirmative action policies aimed at redressing apartheid inequalities

- Used as cautionary tale about "what happens" when progressive policies are implemented

Media Ecosystem

Fox News/Tucker Carlson Pipeline:

- Tucker Carlson's August 22, 2018 segment directly prompted Trump's tweet hours later

- Carlson falsely claimed South Africa was "seizing land from his own citizens without compensation because they are the wrong skin color"

- Created direct feedback loop: Fox segment ? Trump tweet ? policy directive

Social Media Amplification:

- Trump retweeted accounts like @WhiteGenocideTM in 2016

- Musk uses X (Twitter) to repeatedly promote "white genocide" claims to hundreds of millions of followers

- Grok AI programmed to insert narrative into conversations

- Creates appearance of grassroots concern through coordinated amplification

The "Great Replacement" Connection

The South African "white genocide" narrative is explicitly linked to broader white supremacist theories:

- Great Replacement Theory: Belief that white populations are being deliberately replaced by non-white populations

- Eurabia: Conspiracy theory about Muslims taking over Europe

- Kalergi Plan: Antisemitic conspiracy theory about Jewish plot to destroy European races

These theories are used interchangeably and share common themes:

- Demographics as existential threat

- White victimhood

- Conspiracy by elites/minorities

- Violence as defensive necessity

VI. Impact and Consequences

U.S. Refugee Policy Distortion

- Afghans who aided U.S. military: Deportation protections ended

- Syrian refugees: Trump called them potential "trojan horse" for terror

- 600,000 people in refugee pipeline: Processing halted

- White Afrikaners: Sole exception to global refugee ban

South Africa-U.S. Relations

- All U.S. aid cut off, including potential impact on PEPFAR (HIV/AIDS treatment for millions)

- South African ambassador expelled

- Diplomatic crisis over false accusations

- Ramaphosa forced to publicly defend against genocide accusations

- Strengthens hand of actual far-left extremists (EFF) who can point to Western hostility

Domestic South African Impact

- Reopened racial wounds from apartheid era

- Emboldened secessionist movements (some Afrikaners calling for separate territory)

- Increased racial tensions

- Undermined efforts at national reconciliation

- Provided ammunition to both far-left and far-right extremists

VII. Expert Assessments and Rebuttals

International Organizations

United Nations: No recognition of genocide

Genocide Watch: South Africa not listed among countries at risk

Human Rights Watch: No evidence of systematic racial targeting

Anti-Defamation League: "Repeatedly stated that the claims of a white genocide in South Africa are baseless"

South African Authorities

— Julius Malema, Economic Freedom Fighters leader (ironically, the same figure whose "Kill the Boer" song Musk and Trump cite as evidence)

— Institute for Security Studies, South Africa

Academic Analysis

Professor Thula Simpson (historian): Describes the song "Kill the Boer" as "part of the theatre of mass insurrection" during the anti-apartheid struggle, not a call for actual violence. Notes that in post-apartheid South Africa, "there has never been anything close to an attempted genocide of white South Africans."

Professor Quinn Slobodian (Boston University): "The centrality of South Africa for the far right and for neoliberals is quite extraordinary."

Jonny Steinberg (columnist): Argues Musk's views "echo those of many white South Africans in the 1970s and 1980s," noting his warnings of "imminent civil war" and preoccupation with "gangs of dark-skinned men raping underage white girls" and "white people having too few children to reproduce themselves."

VIII. The Deeper Ideological Roots

Apartheid's Lasting Influence

The worldview of Musk, Thiel, and others shaped by apartheid reflects specific characteristics:

- Privilege as natural order: Massive racial inequality viewed as result of merit, not systemic oppression

- Government as oppressor: All state intervention seen as threat to "liberty" (whether apartheid state or democratic government)

- Demographic anxiety: Fear of majority populations gaining power

- Libertarianism without liberty: Opposition to democracy when it threatens elite interests

— Jonny Steinberg, analysis of Musk's political rhetoric

From Swakopmund to Silicon Valley

The town where Thiel attended school—Swakopmund, Namibia—provides a window into the ideological milieu:

- German colonial outpost

- Site of Herero and Nama genocides (1904-1908)

- Memorial to genocide perpetrators maintained

- Open Nazi sympathies into 1970s-80s

- Hitler's birthday celebrations

- Swastika flags sold in gift shops

- School with corporal punishment and mandatory uniforms

- Workers in uranium mines lived in conditions "not far removed from indentured servitude"

The Palantir Connection

Thiel's company Palantir, named after the all-seeing orbs in Lord of the Rings, reveals the intersection of apartheid influence and current power:

- Founded in 2004 with CIA seed money

- Provides surveillance technology to governments and militaries worldwide

- Contracted for ICE deportations

- Supplies Israel with AI systems to track Palestinians

- £480 million UK NHS data contract

- Used for "dragnet" surveillance

The contradiction: libertarian rhetoric about freedom combined with building infrastructure for mass surveillance and state control—as long as it targets the "right" people.

IX. Conclusion: Fantasy as Policy

The Central Reality: Every major international organization, independent research institution, and South African authority—including those sympathetic to farmers—agrees there is no "white genocide" in South Africa. The Trump administration's policy is based entirely on a white supremacist conspiracy theory that has been repeatedly and thoroughly debunked.

What Actually Exists in South Africa

- High crime rates affecting all racial groups

- Farm attacks as part of broader violent crime problem

- Legitimate security concerns for rural communities

- Complex political debates over land reform

- Economic inequality rooted in apartheid history

- Affirmative action policies aimed at redress

- Functioning multiracial democracy with peaceful power transitions

What Does Not Exist

- Genocide by any credible definition

- Racial targeting of white farmers

- Mass land seizures without compensation

- Government-sponsored violence against whites

- Murder rates for farmers higher than general population

- Any systematic persecution justifying refugee status

The Political Function of the Lie

The "white genocide" narrative serves multiple purposes for the Trump administration and its tech oligarch advisors:

- Racial Resentment Politics: Validates white grievance and portrays diversity initiatives as existential threats

- Immigration Weaponization: Justifies explicitly racial refugee preferences

- Anti-Democratic Precedent: South Africa's majority-rule democracy depicted as cautionary tale

- Geopolitical Retaliation: Punishes South Africa for ICJ case against Israel and relationships with Iran

- Tech Oligarch Interests: Advances Musk's complaints about affirmative action affecting Starlink licensing

- Far-Right Alliance Building: Strengthens ties with global white nationalist movements

The Broader Pattern

This case study reveals how demonstrably false claims can become official U.S. policy when:

- Promoted by figures with enormous wealth and platform (Musk, Thiel)

- Amplified through captured media ecosystem (Fox News)

- Embraced by leader willing to ignore evidence (Trump)

- Serving ideological narrative (white victimhood)

- Opposed by institutions with declining credibility (mainstream media, international organizations)

The Ultimate Irony

The most economically privileged group in South Africa—white Afrikaners who benefited from apartheid and continue to own the vast majority of commercial farmland—have been designated as the sole group worldwide eligible for U.S. refugee protection during a period when the Trump administration has:

- Ended protections for Afghan allies who face Taliban execution

- Halted resettlement for Syrians fleeing civil war

- Stopped processing for hundreds of thousands in the refugee pipeline

- Described refugees as competing for American resources

- Expressed preference for immigrants from "nice countries" like Norway over Africa

Meanwhile, the Afrikaner community itself—the alleged victims—largely rejects the refugee designation, with major organizations stating they prefer to remain in South Africa despite disagreements with the government.

Final Assessment

The "white genocide" narrative is not a good-faith misunderstanding or legitimate policy difference. It is a deliberate fabrication, rooted in white supremacist ideology, promoted by tech oligarchs shaped by apartheid, amplified through right-wing media, and weaponized to reshape U.S. refugee policy along explicitly racial lines.

The fact that this fantasy has become official U.S. policy—complete with executive orders, diplomatic ruptures, and the actual resettlement of "refugees" facing no credible persecution—represents a profound failure of factual accountability in American governance and a troubling victory for those seeking to normalize white nationalist narratives in mainstream politics.

- Farm murders in South Africa (2024): ~50-60 across all races

- Total murders in South Africa (2024): 25,423

- Farm murders as percentage of total: 0.2%

- White South Africans as percentage of population: 7.2%

- Commercial farmland owned by whites: 72%

- Land actually seized without compensation under new law: 0

- International organizations recognizing genocide: 0

- South African Afrikaners resettled as refugees under Trump order: 59 (as of May 2025)

- South Africans who expressed interest: 67,000

- Percentage of interested parties who are actually fleeing persecution: Unknown, but statistically zero based on evidence

The claims that white South Africans are victims of genocide gained traction in certain political circles since the end of apartheid. Through careful analysis of the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, examination of empirical data on violence and mortality in South Africa, and review of scholarly literature, analysis concludes that while South Africa faces serious challenges with violent crime affecting all population groups, the available evidence does not support claims of genocide as defined by international law.

I. Introduction

Since the transition to majority rule in 1994, South Africa has confronted numerous challenges in building a multiracial democracy from the ruins of apartheid. Among the most politically charged debates has been the question of violence against white South Africans, particularly white farmers. Claims that this violence constitutes genocide have circulated widely in international media and political discourse, gaining particular prominence in far-right political movements and among some conservative commentators in Western nations. These allegations have occasionally influenced foreign policy discussions, most notably when former U.S. President Donald Trump directed his Secretary of State to investigate alleged land seizures and the "large scale killing of farmers" in South Africa in August 2018.1

Since the transition to majority rule in 1994, South Africa has confronted numerous challenges in building a multiracial democracy from the ruins of apartheid. Among the most politically charged debates has been the question of violence against white South Africans, particularly white farmers. Claims that this violence constitutes genocide have circulated widely in international media and political discourse, gaining particular prominence in far-right political movements and among some conservative commentators in Western nations. These allegations have occasionally influenced foreign policy discussions, most notably when former U.S. President Donald Trump directed his Secretary of State to investigate alleged land seizures and the "large scale killing of farmers" in South Africa in August 2018.1

The assertion that genocide is occurring in South Africa is extraordinarily serious, invoking the gravest crime recognized under international law. The term "genocide" carries specific legal meaning codified in the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, which emerged from the international community's response to the Holocaust. Given the weight of this accusation and its potential implications for international relations, humanitarian intervention, and South Africa's domestic politics, rigorous examination of these claims against established legal frameworks and empirical evidence is essential.

This analysis proceeds from the premise that genocide claims must be evaluated according to the strict legal standards established in international law, not according to political rhetoric or emotional appeals. The paper examines whether the situation in South Africa satisfies the specific elements required to constitute genocide under the UN Convention, analyzes available statistical evidence on violence and mortality patterns, contextualizes contemporary violence within South Africa's historical trajectory, and reviews the scholarly consensus on these questions. The objective is to provide a factual, evidence-based assessment that distinguishes between legitimate concerns about crime and violence in South Africa and unsupported claims of systematic genocidal intent.

II. The Legal Framework: Defining Genocide Under International Law

A. The UN Genocide Convention

The foundation of international genocide law is the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on December 9, 1948, and entered into force on January 12, 1951. The Convention was drafted in the immediate aftermath of World War II and the Holocaust, representing the international community's determination to prevent such atrocities in the future. South Africa is a party to the Convention, having ratified it on December 10, 1998, thereby accepting its legal obligations under the treaty.2

Article II of the Convention provides the authoritative definition of genocide in international law:

Article II: In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

This definition has been incorporated into the statutes of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, and the International Criminal Court. It has been consistently applied by international courts and is widely regarded as reflecting customary international law binding on all states.3

B. Elements Required for Genocide

Genocide requires the satisfaction of two fundamental elements: the actus reus (prohibited acts) and the mens rea (specific intent). The actus reus comprises the five categories of acts enumerated in Article II, which range from killing to forcible transfer of children. However, the mere commission of these acts, even on a substantial scale, does not alone constitute genocide. What distinguishes genocide from other serious crimes, including crimes against humanity and war crimes, is the specific mental element: the intent to destroy a protected group as such, in whole or in part.4

The International Court of Justice has emphasized that genocide is characterized by its dolus specialis, a special intent that must be convincingly demonstrated. In the landmark case of Bosnia and Herzegovina v. Serbia and Montenegro, the Court stated that "the definition of genocide requires the demonstration of a special intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a group as defined in Article II of the Convention."5 This special intent must be directed at the destruction of the group itself, not merely at individuals who happen to be members of that group. As the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda explained, "the victim is chosen not because of his individual identity, but rather on account of his membership in a national, ethnical, racial or religious group."6

The requirement that the perpetrator intend to destroy the group "in whole or in part" does not mean that any attack on group members constitutes genocide. International jurisprudence has established that the part targeted must be substantial, either numerically or in terms of its significance to the group's survival. The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda held that "the intent must be to destroy at least a substantial part of the particular group."7 Furthermore, courts have recognized that the destruction must be of the group as a distinct entity, not merely the elimination of its members from a particular geographic area, unless that elimination forms part of a broader destructive intent.

C. Protected Groups Under the Convention

The Convention protects four categories of groups: national, ethnical, racial, and religious. Notably absent from this list are political groups, social groups, economic groups, and groups defined by other characteristics. The exclusion of political groups was deliberate, resulting from compromises during the Convention's drafting, particularly due to objections from the Soviet Union and other states concerned about potential application to their internal affairs.8

In the South African context, white South Africans could potentially be considered a racial group under the Convention, though the precise boundaries of racial classification in South Africa remain complex due to the country's history of legal racial categorization under apartheid and the fluidity of racial identity. The Convention's framers did not provide detailed guidance on how these group categories should be defined, leaving some interpretive questions to be resolved through subsequent legal practice and scholarship. International tribunals have generally employed a combined approach, examining both objective factors (how the group is perceived externally) and subjective factors (how members identify themselves).9

III. Historical Context: South Africa's Transition from Apartheid

A. The Apartheid Legacy

To understand contemporary South Africa, one must begin with the apartheid system that governed the country from 1948 to 1994. Apartheid was a comprehensive system of racial segregation and discrimination enforced through legislation and state violence. The Population Registration Act of 1950 classified all South Africans into racial categories, while the Group Areas Act confined each racial group to designated residential and business areas. Black South Africans were denied citizenship in their own country, instead being assigned to ethnic "homelands" or Bantustans. Political representation, economic opportunity, education, healthcare, and virtually every aspect of life were structured around racial hierarchy, with the white minority enjoying overwhelming privilege and the black majority subjected to systematic oppression and exploitation.10

The violence of apartheid was both structural and direct. The state employed arbitrary detention, torture, assassination, and military force to maintain the system. The African National Congress and other liberation movements resorted to armed struggle after peaceful protest was met with massacres such as the Sharpeville shooting of 1960, in which police killed 69 unarmed protesters. By the 1980s, South Africa was engulfed in violent conflict, with the state imposing repeated states of emergency and deploying security forces in townships across the country. International isolation increased as the anti-apartheid movement gained global support, leading to comprehensive economic sanctions and cultural boycotts.11

B. The Negotiated Transition

The transition from apartheid to democracy was accomplished through negotiation rather than military defeat or revolution. After President F.W. de Klerk unbanned liberation movements and released Nelson Mandela from prison in 1990, the country entered a period of intense negotiation punctuated by continuing violence. The Convention for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA) brought together representatives from across the political spectrum to negotiate a new constitutional order. After significant obstacles, including the assassination of South African Communist Party leader Chris Hani and threats of civil war, agreements were reached that allowed for South Africa's first democratic elections in April 1994.12

The negotiated nature of the transition had profound implications. Unlike revolutionary transformations that completely displace existing power structures, South Africa's transition preserved substantial elements of the old order while fundamentally restructuring political power. The new constitution, adopted in 1996, is widely regarded as one of the most progressive in the world, enshrining extensive human rights protections and establishing a constitutional court with the power to review all legislation. However, economic power remained concentrated in the hands of the white minority, and the security services, while formally integrated, retained many personnel from the apartheid era.13

C. Post-Apartheid Challenges

The post-apartheid period has been characterized by both remarkable achievements and severe ongoing challenges. South Africa avoided the civil war that many observers feared, maintained democratic institutions through multiple peaceful transfers of power, and built a robust constitutional framework. The country has achieved significant expansion in access to basic services, with millions gaining access to electricity, clean water, and housing. Social grants have expanded dramatically, providing crucial support to the poorest citizens.14

However, South Africa continues to grapple with the legacy of apartheid. The country has among the highest levels of income inequality in the world, with wealth and poverty still largely following racial lines. Unemployment remains stubbornly high, particularly among young black South Africans, contributing to social instability. Most critically for this analysis, South Africa has experienced persistently high rates of violent crime, including murder, assault, and robbery. This violence has affected all racial groups, though patterns vary by type of crime and geographic location.15

Land ownership has remained a particularly contentious issue. At the end of apartheid, approximately 87 percent of South Africa's land was owned by white South Africans, who comprised less than 10 percent of the population. This disparity was the direct result of colonial dispossession and apartheid-era legislation such as the Natives Land Act of 1913, which prohibited African ownership of land outside designated reserves. The post-apartheid government has pursued land reform through a "willing buyer, willing seller" approach, though progress has been slower than many desired. Debates over land reform have intensified in recent years, with some political parties, particularly the Economic Freedom Fighters, calling for expropriation without compensation. In 2018, the African National Congress announced it would seek to amend the constitution to allow such expropriation, though this remains a subject of ongoing debate and has not yet been implemented.16

IV. The Empirical Evidence: Crime and Violence in Contemporary South Africa

A. General Crime Statistics

South Africa faces a serious crime crisis that affects all segments of its population. According to statistics released by the South African Police Service, the country recorded 27,494 murders in the 2022/2023 reporting year, representing a murder rate of approximately 45 per 100,000 population. This places South Africa among the countries with the highest murder rates globally, comparable to nations experiencing significant internal conflict. By comparison, the global average murder rate is approximately 6.1 per 100,000, and the average for the African continent is approximately 13.0 per 100,000.17

The geographic and demographic distribution of this violence is complex. Murder rates are highest in the Western Cape province, particularly in the Cape Flats area of Cape Town, where gang violence and competition in illegal economies drive homicide rates exceeding 100 per 100,000 in some communities. The Eastern Cape, KwaZulu-Natal, and Gauteng provinces also experience high levels of violence. Rural areas generally have lower murder rates than urban areas, though this varies by region. The majority of murder victims in South Africa are young black men, reflecting both demographic realities and the concentration of violence in townships and informal settlements where the black population is predominantly located.18

Other violent crimes are similarly prevalent. The same reporting period recorded 9,556 sexual offenses, 55,829 assaults with intent to inflict grievous bodily harm, and 44,757 robberies with aggravating circumstances. Carjacking, home invasions, and armed robbery affect all communities, though security measures and private security services provide some protection to wealthier (disproportionately white) neighborhoods. South Africa's violent crime must be understood within the context of high inequality, limited economic opportunity, weak state capacity in some areas, and social disruption stemming from apartheid's systematic destruction of black family and community structures.19

B. Farm Attacks and Farm Murders

Central to claims of genocide against white South Africans are statistics regarding farm attacks and farm murders. AgriSA, an agricultural industry association, has maintained statistics on these incidents since the establishment of the Committee of Inquiry into Farm Attacks in 2001, though earlier data exists from other sources. A farm attack is defined as "an act of violence committed with the intent to harm, intimidate, or injure a person residing on, working on, or visiting the farm, or to damage property, livestock, or crops."20 A farm murder refers to cases where these attacks result in death.

According to AgriSA's data, farm attacks have fluctuated over time. The period from 1997-1998 saw a peak of approximately 1,068 reported farm attacks, which declined to approximately 350-400 attacks annually by the mid-2000s, before increasing again to around 500-600 attacks per year in recent years. Farm murders have shown a similar pattern, with 153 recorded in 1998, declining to around 47-74 per year in the 2010s, and fluctuating between 49-81 in recent years. In the 2021/2022 period, there were 51 farm murders recorded.21

These statistics require careful interpretation. First, not all farm attack victims are white. Black farm workers, who significantly outnumber white farm owners, are also victimized in farm attacks, though they receive far less media attention. Second, farms in South Africa are often isolated, making them attractive targets for criminals seeking weapons, vehicles, and valuables with reduced risk of immediate law enforcement response. Third, the rate of farm murders must be contextualized within South Africa's overall murder rate. While any murder is tragic, the farm murder rate, when calculated as a proportion of the farming population, is actually somewhat lower than the national average murder rate, according to analysis by the Institute for Security Studies and other researchers.22

A crucial question for genocide determination is whether farm attacks are motivated by racial animus or by criminal opportunism. Investigations by the South African Police Service have consistently found that the vast majority of farm attacks are motivated by robbery rather than racial hatred. The Rural Protection Plan, implemented in collaboration between police and agricultural organizations, found that in approximately 90 percent of farm attack cases, the primary motive was robbery of firearms, vehicles, money, and other valuables. Victims are often tortured to reveal the location of safes or valuable items, reflecting criminal rather than genocidal intent.23

The political dimension of farm attacks has been complicated by inflammatory rhetoric from some quarters. Julius Malema, leader of the Economic Freedom Fighters party, has led supporters in singing "Kill the Boer," a struggle song from the apartheid era. Courts have ruled on the status of this song multiple times, with the Equality Court finding in 2010 that it constituted hate speech, while a later High Court judgment in 2022 found that its use in the context of liberation struggle history was protected speech. Such rhetoric, while deeply concerning and inflammatory, must be distinguished from actual incitement to violence or evidence of coordinated campaigns of racial violence.24

C. Comparative Analysis of Mortality by Race

A comprehensive assessment of genocide claims requires examining mortality patterns across South Africa's racial groups. Statistics South Africa, the country's official statistical service, provides demographic data that illuminates these patterns. Life expectancy statistics show that black South Africans have lower life expectancy than white South Africans, reflecting ongoing health and socioeconomic disparities. In 2021, life expectancy at birth for white males was 71.3 years compared to 60.8 years for black males; for females, the figures were 77.5 years for whites and 66.7 years for blacks.25

If genocide were occurring against white South Africans, one would expect to see either a declining white population through excess mortality or a dramatic increase in violent deaths among this group compared to others. The data does not support this hypothesis. Statistics South Africa's mid-year population estimates show that the white population has remained relatively stable, declining slightly from approximately 4.52 million in 2002 to approximately 4.48 million in 2022. This modest decline is attributable primarily to emigration and lower fertility rates rather than excess mortality. The white population represents approximately 7.3 percent of South Africa's total population of 60.6 million.26

In terms of violent death, the burden falls overwhelmingly on black South Africans. The South African Medical Research Council has analyzed patterns of homicide and found that young black men experience by far the highest rates of murder victimization. The concentration of violence in township areas, where black communities are predominantly located, means that the absolute number of black South Africans killed annually far exceeds the number of white South Africans killed. While farm murders receive significant media attention, they represent a small fraction of South Africa's total homicides.27

V. Government Policy and Intent

A. Constitutional and Legal Protections

The question of genocide necessarily implicates government policy and intent. South Africa's Constitution explicitly prohibits discrimination on the basis of race and protects the rights of all citizens regardless of racial classification. Section 9 of the Constitution guarantees equality before the law and explicitly prohibits unfair discrimination based on race, among other grounds. The Promotion of Equality and Prevention of Unfair Discrimination Act of 2000 provides detailed protections against discriminatory practices. South African courts have demonstrated willingness to enforce these protections, striking down discriminatory practices and requiring government compliance with constitutional standards.28

The constitutional framework specifically protects property rights while also providing for limited expropriation in the public interest subject to compensation. Section 25 of the Constitution, known as the property clause, has been the subject of intense debate regarding land reform. While amendments have been proposed to facilitate land redistribution, any such measures would remain subject to constitutional scrutiny and could not be implemented in a manner that targets a racial group for destruction. The Constitutional Court serves as a check on potential governmental overreach, having ruled against government positions in numerous cases.29

B. Law Enforcement Response to Farm Attacks

The South African government's response to farm attacks has included both specialized policing initiatives and general crime prevention strategies. The South African Police Service established dedicated Rural Safety Strategy initiatives, including specialized units focused on farm attacks. Provincial governments have collaborated with agricultural organizations to develop response protocols and increase police visibility in rural areas. While these efforts have faced criticism for being insufficiently resourced or coordinated, they demonstrate government recognition of the problem and efforts to address it, which would be inconsistent with genocidal intent.30

The government has also repeatedly condemned farm attacks and murders at the highest levels. President Cyril Ramaphosa and other government officials have stated unequivocally that farm murders are criminal acts that will be prosecuted to the full extent of the law. The National Prosecuting Authority has prioritized farm attack cases, and courts have imposed severe sentences on convicted perpetrators. In numerous cases, individuals convicted of farm murders have received life sentences. This pattern of prosecution and punishment is fundamentally incompatible with a state policy of genocide.31

C. Land Reform Policy

Land reform remains perhaps the most contentious policy area relevant to genocide claims. The South African government has pursued land redistribution through several mechanisms: restitution (returning land to those dispossessed under apartheid), redistribution (voluntary land transfer programs), and tenure reform (securing land rights for farm workers and informal occupants). The pace of land reform has been slower than many desired, with estimates suggesting that less than 10 percent of commercial farmland has been transferred to black ownership since 1994, far short of initial targets.32

Debates over expropriation without compensation intensified in 2018 when the African National Congress announced it would pursue a constitutional amendment to permit such expropriation under certain circumstances. This announcement generated significant controversy and contributed to international concerns about property rights in South Africa. However, as of 2025, no such constitutional amendment has been enacted, and existing land reform continues to operate within the constitutional framework requiring compensation. Moreover, even the proposed amendments were framed in terms of addressing historical injustice and economic inequality rather than targeting white South Africans for elimination as a group.33

It is crucial to distinguish between land reform aimed at addressing historical dispossession and policies aimed at destroying a group. Measures to redistribute land, even if economically disruptive to current landowners, do not constitute genocide unless accompanied by the specific intent to destroy the group as such. International law recognizes that states may undertake land reform and address historical injustices, provided such measures comply with due process and international human rights standards. The situation in South Africa, while politically charged, has not involved mass expropriation or systematic deprivation of white South Africans' ability to exist as a group.34

VI. International and Scholarly Assessment

A. United Nations and International Organizations

International bodies that monitor human rights and genocide have not concluded that genocide is occurring in South Africa. The United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect, which is mandated to serve as an early warning mechanism for genocide risk, has not issued alerts regarding South Africa. The office monitors situations globally using a framework of risk factors, and while South Africa faces challenges related to inequality, crime, and political tension, it does not display the pattern of state-orchestrated violence against a particular group that characterizes genocide.35

The UN Human Rights Council's Universal Periodic Review of South Africa, conducted most recently in 2022, identified concerns regarding violent crime, inequality, and the treatment of migrants, but made no findings of genocide. International human rights organizations, including Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, have documented various human rights concerns in South Africa, including police brutality, violence against women, and xenophobic attacks, but have not concluded that white South Africans face systematic violence meeting the genocide threshold.36

B. Academic and Research Perspectives

The scholarly community studying genocide and mass atrocities has overwhelmingly rejected claims that white South Africans are victims of genocide. Gregory Stanton, president of Genocide Watch, initially placed South Africa at Stage 6 ("preparation") on his organization's ten-stage genocide model in 2012, primarily based on farm murder statistics and concerns about inflammatory political rhetoric. However, this assessment was controversial among genocide scholars and was based on a framework that identifies risk factors rather than actual genocide. By 2022, Stanton acknowledged that while farm murders remained a concern, there was no evidence of organized state involvement or systematic elimination of white South Africans.37

Academic analyses of farm attacks consistently emphasize the criminal motivation behind most incidents. Biljon Viljoen, a researcher who has studied farm attacks extensively, found that the patterns of farm attacks are consistent with criminal behavior rather than political or racial targeting. Victims include farm workers and residents of all races, and the modus operandi focuses on obtaining valuables rather than elimination of victims. Johan Burger of the Institute for Security Studies has noted that while farm attacks deserve serious attention and improved law enforcement response, characterizing them as genocide is unsupported by evidence and unhelpful for developing effective solutions.38

Comparative genocide studies provide additional context. Scholars who study genocide emphasize that the crime is characterized by systematic, organized violence directed by state actors or powerful organized groups with the specific intent to eliminate a target population. Alexander Hinton, director of the Center for the Study of Genocide and Human Rights at Rutgers University, has noted that South Africa lacks the key indicators of genocide: there is no systematic state-sponsored violence against white South Africans, no evidence of organized extermination campaigns, and no pattern suggesting intent to destroy the group. The situation is better understood as a high-crime environment affecting all South Africans within the context of difficult post-apartheid transition.39

C. Political Instrumentalization of Genocide Claims

Scholars have also examined how genocide claims have been politically instrumentalized. Several analysts have noted that assertions of "white genocide" in South Africa have been promoted primarily by far-right political movements seeking to mobilize opposition to immigration, multiculturalism, and racial equality in Western nations. These narratives serve political objectives in countries far from South Africa while contributing little to understanding or addressing the actual security challenges facing South Africans of all races. The framing of farm attacks as genocide while ignoring South Africa's far larger crisis of violence affecting predominantly black South Africans reflects political agenda-setting rather than objective analysis.40

Within South Africa, some political actors have used genocide claims as part of resistance to transformation and land reform. By framing measures to address apartheid's legacy as existential threats requiring international intervention, these narratives seek to delegitimize the post-apartheid order and preserve existing racial hierarchies in property ownership and economic power. Conversely, some voices within South African politics have minimized or dismissed concerns about farm attacks, treating them merely as political weapons rather than legitimate security concerns. This polarization has impeded development of effective, evidence-based responses to rural crime.41

VII. Application of the Legal Framework to the South African Context

A. Assessment of the Actus Reus

Applying the Genocide Convention's framework to South Africa requires examining whether the prohibited acts enumerated in Article II are occurring on a scale and in a manner consistent with genocide. Regarding Article II(a), killing members of the group, it is undeniable that white South Africans, including farmers, are victims of homicide in South Africa. However, the rate of homicide victimization among white South Africans is lower than the national average and substantially lower than rates affecting young black men in township areas. The absolute number of white South Africans killed annually represents a small fraction of South Africa's total murder victims. While each killing is tragic and deserves justice, the pattern does not suggest systematic killing directed at eliminating white South Africans as a group.42

Regarding Article II(b), causing serious bodily or mental harm, white South Africans, like all South Africans, are affected by the country's high rates of violent crime, including assault and robbery. Farm attacks often involve torture and serious injury. However, this violence is not occurring on a scale or in a pattern that suggests an organized campaign to destroy white South Africans as a group. The widespread nature of violent crime affecting all population groups, combined with the criminal motivations behind most incidents, undermines claims that harm to white South Africans constitutes genocide rather than participation in South Africa's general crime crisis.

Articles II(c), (d), and (e) regarding conditions of life calculated to bring about physical destruction, measures to prevent births, and forcible transfer of children are clearly not applicable to the South African situation. White South Africans retain access to healthcare, education, economic opportunity, and social services. There are no policies or practices aimed at preventing reproduction among white South Africans or removing their children. While land reform debates continue, there has been no systematic deprivation of the means of existence for white South Africans as a group.

B. Assessment of Genocidal Intent

The critical element in any genocide determination is the specific intent to destroy a protected group as such, in whole or in part. This element is what distinguishes genocide from other serious crimes, and international jurisprudence has consistently required convincing evidence of this special intent. In the South African context, there is no credible evidence of genocidal intent directed against white South Africans by either the state or organized non-state actors.

The South African government's policies, statements, and actions are inconsistent with genocidal intent. The constitutional framework protects all citizens regardless of race, government officials have condemned farm attacks and violent crime, law enforcement investigates and prosecutes perpetrators of violence against white South Africans, and courts impose severe sentences on those convicted. Land reform, while controversial, is framed in terms of addressing historical injustice rather than eliminating white South Africans. The continuation of white participation in all aspects of South African life, including politics, business, academia, and civil society, contradicts claims of genocidal intent.43

Evidence regarding the motives of individual perpetrators of farm attacks points to criminal opportunism rather than genocidal intent. Police investigations consistently find that farm attacks are motivated by desire for guns, vehicles, cash, and other valuables. The targeting of isolated rural properties with perceived wealth, rather than systematic selection of victims based solely on racial identity, suggests criminal rather than genocidal logic. While some incidents may involve racial animus, this does not establish the systematic, organized intent to destroy a group required for genocide.

Inflammatory rhetoric, including singing of "Kill the Boer" and other provocative statements by political figures, is deeply concerning and contributes to racial tension. However, rhetoric alone, without connection to actual plans or implementation of destructive policies, does not establish genocidal intent under international law. The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda distinguished between speech that constitutes direct incitement to genocide and political speech, however offensive, that does not rise to that level. The South African context lacks evidence of such speech being connected to organized campaigns of violence or state policy aimed at destroying white South Africans.44

C. Comparative Analysis with Recognized Genocides

Comparing the situation in South Africa with recognized cases of genocide illuminates the distinction between high levels of criminal violence and systematic genocide. The Holocaust, the Convention's paradigm case, involved state-orchestrated industrial killing, with dedicated infrastructure and bureaucracy aimed at eliminating Jews and other targeted groups. The Rwandan genocide of 1994 involved systematic killing of Tutsis and moderate Hutus through coordinated state and militia action, resulting in approximately 800,000 deaths over 100 days. The Srebrenica massacre of 1995 involved the deliberate execution of more than 8,000 Bosnian Muslim men and boys by Bosnian Serb forces. In each case, clear evidence existed of organized, systematic violence with explicit genocidal intent.45

South Africa presents a fundamentally different picture. Violence is not organized by the state or coordinated groups against white South Africans specifically. The death toll, while tragic, is orders of magnitude lower than in recognized genocides and represents a small fraction of South Africa's overall homicide victims. There is no pattern of systematic elimination, no evidence of coordinated campaigns, and no articulated policy of destruction. The situations are legally and factually distinct.

VIII. Alternative Frameworks for Understanding South African Violence

A. Post-Conflict Crime Transitions

South Africa's high crime rates are better understood through frameworks analyzing post-conflict societies and the criminalization that often accompanies political transitions. Countries emerging from civil war, authoritarian rule, or other forms of violent conflict typically experience elevated crime rates as the structures of violence transition from political to criminal forms. The militarization of society during conflict, circulation of weapons, normalization of violence, and weak state capacity contribute to criminal violence even after political settlements are reached.46

South Africa's transition involved elements of these dynamics. The armed struggle against apartheid, while necessary given the regime's intransigence, created networks of armed individuals and normalized violence as a means of resolving disputes. The state security apparatus, while formally integrated into new democratic structures, carried over personnel and practices from the apartheid era. Economic dislocation and the proliferation of firearms in civilian hands contributed to criminal opportunity. Understanding South African violence in this framework illuminates patterns that genocide claims obscure, including the fact that violence is predominantly intra-racial, occurs primarily in marginalized communities, and reflects criminal rather than political or racial logic.47

B. Inequality, Opportunity, and Crime

Criminological research consistently identifies inequality, particularly when combined with limited economic opportunity and weak state capacity, as a powerful driver of violent crime. South Africa exhibits extreme inequality, with a Gini coefficient among the world's highest. Wealth and opportunity remain largely structured along racial lines due to apartheid's legacy. Youth unemployment exceeds 50 percent in many black communities, creating conditions where criminal activity becomes attractive relative to limited legitimate opportunities. This is not to excuse criminal behavior, but rather to identify structural factors that explain South Africa's crime crisis across racial lines.48

Farm attacks specifically can be understood within this framework. Rural areas often have limited law enforcement presence, farms may possess valuable and mobile assets (vehicles, guns, cash), and the isolation of rural properties reduces the risk of immediate response. From a criminological perspective, these factors explain why farms become targets without requiring racial motivation. The involvement of farm workers or former workers in some attacks further suggests that knowledge of property layout and asset location, rather than racial targeting, drives criminal selection of victims.49

IX. Implications and Recommendations

A. Consequences of Mischaracterizing Violence as Genocide

Characterizing South Africa's violence as genocide when the evidence does not support such a conclusion carries significant negative consequences. First, it trivializes actual genocide, undermining the power of the term to identify and mobilize response to the world's gravest crime. If every situation of elevated violence or intergroup tension is labeled genocide, the term loses its specific meaning and its capacity to prompt international action becomes diluted. Second, genocide claims distort understanding of South Africa's actual challenges, impeding development of effective responses. If farm attacks are understood as genocide rather than crime, attention focuses on racial mobilization rather than effective policing, rural development, and addressing the root causes of criminal violence.50

Third, genocide narratives in the South African context often serve to deflect from ongoing structural racism and inequality that apartheid created. By framing white South Africans as victims of genocidal violence while minimizing the far greater violence affecting black South Africans and the continuing effects of apartheid's dispossession, these narratives reinforce rather than challenge racial hierarchy. Fourth, international promotion of genocide claims can damage South Africa's international relationships and economic prospects, potentially undermining the very stability that would help reduce violence. Foreign disinvestment driven by exaggerated genocide claims would harm all South Africans, but particularly the poor and marginalized who most need economic development.51

B. Addressing South Africa's Actual Security Challenges

South Africa's high rates of violent crime require sustained, comprehensive response. Effective approaches must include strengthening law enforcement capacity and accountability, improving criminal justice system functioning, addressing the proliferation of illegal firearms, investing in rural policing and infrastructure, and most fundamentally, reducing inequality and expanding economic opportunity. Programs that integrate former combatants, provide youth employment, strengthen community-police relations, and address trauma and violence normalization have shown promise in various contexts and deserve support in South Africa.52

Farm security specifically requires practical measures including improved communication infrastructure in rural areas, coordination between farmers and police, implementation of the Rural Safety Strategy's recommendations, and addressing labor relations and rural poverty. International cooperation in law enforcement capacity building, particularly through programs like the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime's initiatives, can support South African efforts. These practical approaches offer far more promise than inflammatory rhetoric or international interventions based on unfounded genocide claims.53

C. Addressing Inflammatory Rhetoric

While inflammatory political rhetoric does not constitute genocide, it contributes to racial tension and can incite violence. Political leaders across South Africa's spectrum should exercise responsibility in their public statements, avoiding language that dehumanizes any group or appears to legitimize violence. The singing of "Kill the Boer" and similar struggle songs, while protected as historical political expression in some contexts, should be approached with sensitivity to their impact on intergroup relations in contemporary South Africa. Similarly, exaggerated claims of genocide or characterizations of all black South Africans as threats serve only to deepen divisions.54

Civil society organizations, religious institutions, academic bodies, and other sectors of South African society have important roles in promoting dialogue, countering hate speech, and building bridges across racial divisions. Truth and reconciliation processes, while having limitations, demonstrated the power of acknowledging historical injustice while seeking common ground. Continued efforts to build a shared national identity while respecting South Africa's diversity remain essential to long-term stability and reduction of violence.

X. Conclusion

This analysis has examined claims that white South Africans are victims of genocide through the lens of international law, empirical evidence, and scholarly research. The conclusion is clear: while South Africa faces serious challenges with violent crime affecting all its people, the available evidence does not support claims of genocide against white South Africans as defined by the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.