Calais Border Fence

The most famous European example of the construction of foreclosure infrastructure is the British-funded kilometers of white fence erected around the French port of Calais. They were supposed to prevent attempts to get through the port to Great Britain. Along the highway leading to the Channel Tunnel, there is over 40 km of fencing topped with coils of barbed wire. The densely woven mesh panel system repels attempts to cut or climb. Along the road, near the site of the former refugee camp, there is a four-meter-long concrete wall. The port is monitored and trucks pass through scanners that can detect the beating of the human heart.

Calais is directly opposite to the harbor of Dover, distant only about thirty miles. The water separating the coast of England from that of France is known in the United Kingdom as the English Channel, and in France as La Manche. Dover Strait, 18 miles wide at its narrowest part, separates the SE coast of England from the N coast of France. The shipping lanes in Dover Strait and the S part of the North Sea are among the busiest in the world.

The Allies had serious doubt as to their ability to hide preparations for a cross channel invasion. Adolf Hitler and the German High Command knew that such an invasion was coming. The Allies sought to convince the Germans that the invasion would come to some other part of Europe so that they would fail to move combat resources to Normandy, France. Hitler and most of his closest advisors believed that the most likely place for the Allied invasion of Europe would be in the Pais de Calais region.

Two or three episodes in the history of English rule in Calais are familiar to all. “Every schoolboy knows" - to use the tiresome phrase of a famous historian — that the burgesses of Calais knelt before Edward III with halters round their necks; that Henry VIII met Francis I near Calais at the Field of Cloth of Gold ; and that Queen Mary made some remark to the effect that Calais would be found lying in her heart.

The story of how John of Lancaster, captured by the French and confined at Guisnes, fell in love with a laundry-maid, and, effecting his escape by her aid, became the means whereby Guisnes was captured for the English, may be an eighteenth-century fabrication, but the entry of Guise into Calais disguised as a peasant rivals Alfred's venturesome entry into the Danish camp at Wilton; while the tale of Aymery de Pavia's treachery and the midnight repulse of de Charney's attempt on Calais, or any of the numerous stories in Froissart of duels and frontier fights, and ambushes and tournaments, or last, but not least, the desperate struggle waged in January, 1558, by the English garrison, already vastly outnumbered and without hope of reinforcement, proves that the military history of Calais, like all other border warfare, was not without its picturesque incidents. Its capture formed one of the most discreditable episodes in the history of English misgovernment, and no one loves to dwell on discreditable episodes or upon the events which led up to them.

The army of Edward III arrived before Calais in September 1346, and Calais was surrendered in August 1347. The hardships of the army of Edward III, encamped on the marshes of Picardy during the winter of 1346-47, were considerable. Edward lost nearly all his horses, dysentery was rife in his camp, and the desertions from his army were so numerous that he issued writs to the Sheriffs of counties to arrest all the Knights and menat-arms who had left Calais without his permission, and to lodge them in the Tower of London.

Calais was the first English colony, and as a colony it was in a sense unique, for Calais is the only instance of a colony founded on the Greek system ousting of the native population in favor of an immigrating community of the conquerors. Moreover, it is an almost exact mediaeval counterpart of the modern Gibraltar. Without commerce, Calais would not have been worth keeping, and a garrison would not have existed; without a garrison, the Calais merchants would not for a moment have been safe from French aggression. So that Calais existed for commerce, and the garrison existed for the protection of commerce and Calais. Everything else was subsidiary either to the military or to the commercial organization.

Even from a purely military point of view, Calais was of the utmost utility. All fortresses are expensive, and if their possession is valuable, the money is well spent. Now, Calais was exceedingly valuable, and for these reasons : Strategetically it gave the English a permanent entry into French territory. It must be remarked that the real struggle between French and English was not for the North of France, but for the South-West (old Angevin sentiment had centred round Poitou); consequently, the possession of Calais enabled the English to distract the attention of the French in the North, while their main attack was directed on the South, and kept the French in uncertainty as to where the English intended to strike.

Calais insured that no particular English port was favored unduly by the Sovereign. Moreover, customs and dues could be collected with far greater care, and fraud more easily be detected, at Calais than at an English port. It was more convenient, too, for foreign merchants. The journey was easy to Calais from Flanders, and no risk of shipwreck was involved. Business could be transacted on what was practically neutral ground.

John of Gaunt was indeed in the wrong if he ever believed that Calais was not worth the keeping. With greater reason, however, it may be argued that Calais had by 1558 outlasted its utility. Its loss was disgraceful, but it was not a national disaster, apart from the fact that it involved diminished prestige in Europe; for as a fortress its value was gone. The Hundred Years War was over, and instead of a valuable gate into France, it became merely an obstacle to peace.

At the height of the 2014-15 migrant crisis an estimated 2,000 migrants a night were attempting to enter the UK clandestinely, most concealed in the backs of lorries. Estimates of the numbers of migrants living in the so-called ‘Calais Jungle‘ at that time were as high as 6,000, the majority young men. Physical security at the ports was ineffective and, as a result, there were large-scale incursions at Calais, with migrants storming the port. In 2015, the Eurotunnel shuttle was affected on a nightly basis. On one day, 186 migrants managed to board the shuttle, resulting in one fatality and major disruption to the service.

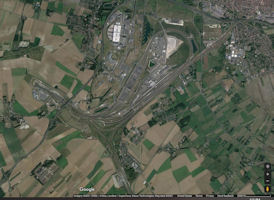

The UK operates border controls in France and Belgium. This allows Border Force officers to check passengers and freight destined for the UK before they begin their journey. These ‘juxtaposed controls’ are in place at Calais and Dunkirk ports, at the Eurotunnel terminal at Coquelles and in Paris Gare du Nord, Lille, Calais-Frethun and Brussels Midi stations for Eurostar passengers. The arrangement is reciprocal, with French officers completing Schengen entry checks in the UK. These arrangements are underpinned by bilateral treaties.

Millions of passengers and billions of pounds worth of legitimate trade pass through juxtaposed border controls each year. With hundreds of ferry and rail crossings each week, the ports in Northern France remain a target for criminals attempting to smuggle dangerous goods and for people looking to enter the UK illegally. Not all clandestine entrants seek asylum. Some look to live and work in the UK undetected, while others, including victims of modern slavery, are prevented from contacting the Home Office by force or with threats. Therefore, the number of asylum claims received, which since 2015 has averaged around 30,000 a year, is not a reliable guide to the scale of clandestine entry.

The term clandestine is used by Border Force to describe an individual who attempts to enter the UK illegally without presenting themselves for examination at passport control, usually concealed in a vehicle or container. Operations to prevent clandestine entry into the UK continue to represent a significant area of focus for Border Force. In the 12-month period from September 2011 to August 2012, over 8,000 clandestines were detected and prevented from entering the UK at juxtaposed controls at Calais, Coquelles and Dunkirk. In 2016, over 56,000 attempts by clandestines to cross the Channel were stopped at the juxtaposed controls. Removing the need for immigration controls on arrival in the UK speeds up journey times and allows transport providers to put on more services.

On 20 August 2015, the Home Secretary and the French Interior Minister signed a Joint Ministerial Declaration concerning cooperation on managing migratory flows in Calais. This noted that: “the UK government has paid for new, high security fencing around the Port of Calais as part of the £12m/€15m Joint Fund, established by [the two ministers] in their joint statement published in September 2014.”

In 2016, both the UK and France reaffirmed their commitment to strengthening the security of the shared border and preserving the vital economic link between the two countries. The UK invested in: new high-security fencing, lighting, CCTV and infrared detection technology at both Calais and Dunkirk ports and Coquelles Terminal; new technology to assist Border Force officers to make detections; additional security guards and search dogs; a secure waiting area for lorries at Calais and Coquelles; and a joint command and control centre to coordinate the law enforcement response to migrants attempting to reach the UK illegally.

Ahead of the Calais camp being closed in November 2016, the Home Secretary announced £36 million to maintain security at the juxtaposed border controls, support the clearance of the camp and to make sure it remained closed.

Between 2016 and 2017 there was a significant reduction (from 33,807 to 15,457) in the number of migrants encountered at Calais attempting to pass clandestinely through the juxtaposed controls. The same was broadly true for Coquelles and Dunkirk. While physical security improvements at and around these ports will have contributed to a reduction in the numbers making it as far as the juxtaposed controls, it is difficult to draw any firm conclusions about the effectiveness of these measures compared with the effect of other factors, notably the dismantling of the Calais ‘Jungle’ migrant camp by the French authorities in October 2016, after which monthly detections fell sharply.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|