Tallinn Line

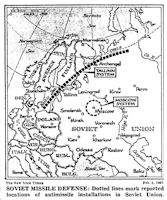

Since 1964 the Soviets began constructing complexes for a new strategic defensive system, which the West called the Tallinn system. Construction was begun initially near Tallinn and other locations in the northwestern USSR. At about the same time modifications were started on three complexes near Leningrad, which had been partially constructed for another defensive system, so that they could accept the new system. The Tallinn Line might have been designed to intercept Polaris A-1 missiles launched in the Barents Sea and passing over Estonia en route to targets in the USSR.

Since 1964 the Soviets began constructing complexes for a new strategic defensive system, which the West called the Tallinn system. Construction was begun initially near Tallinn and other locations in the northwestern USSR. At about the same time modifications were started on three complexes near Leningrad, which had been partially constructed for another defensive system, so that they could accept the new system. The Tallinn Line might have been designed to intercept Polaris A-1 missiles launched in the Barents Sea and passing over Estonia en route to targets in the USSR.

Surface-To-Air (SAM) Upgrade was a controversial Cold War issue that encompassed the essence of the ABM treaty's prohibition against providing a base for a defense of territory. The "SAM upgrade" problem arose in the mid 1960s when the Soviet Union installed a defense system called the "Tallinn" system -- after the name of the Estonian city where the SAM components were first observed. The Americans began to fear that the Tallinn system might be designed for defense against missiles or, at the least, to serve a dual purpose. The so-called "Tallinn" line was believed to be part of an ABM network because the location of the system coincided with the potential flight paths of incoming American missiles.

Like the Soviet ICBM program a few years earlier, Soviet BMD development had become a source of intense controversy within the Intelligence Community. The Army and Air Force saw the Soviets engaged in a massive BMD effort, while the CIA, State Department, National Security Agency, and Naval Intelligence reserved judgment. Under study were the characteristics and capabilities of three known systems: one around Leningrad, apparently started as an air-defense system, which the Soviets suddenly dismantled in 1964 prior to completion; a second, known as the “Tallinn Line,” also for air defense with discernible ABM capabilities; and a third, known as “Galosh,” the most advanced and sophisticated, under construction around Moscow.

In National Intelligence Estimate NIE 11-3-66 "Soviet Strategic Air and Missile Defenses", 17 November 1966, the US intelliigence community assessed that in the SAM role, the Tallinn system represented a considerable improvement over currently operational Soviet SAMs in terms of range (on the order of 100 nm), altitude (up to 100,000 feet), and ability to deal with supersonic targets (up to Mach 3 or 3.5). If the system was designed as an ABM, then data would have to be fed to the complexes from off-site radars in order for them to defend areas large enough to provide a strategic ABM defense. Some of the Tallinn complexes were in locations where they could take advantage of such data from known radars of appropriate types, but some were not. With such data, the Tallinn complexes were assessed as capable of exoatmospheric intercept of incoming ballistic missiles at distances out to about 200 nm, and thus each complex could defend a fairly large area. Without such data, the ABM capabilities of each complex would be seriously reduced and limited to local and self-defense.

The NIE noted "Although we believe that the mission of the Tallinn system is defense against the airborne threat, we have also assessed its capabilities against ballistic missiles.11 this assessment, we have assumed alternate characteristics for a missile, which we believe are reasonable for the ABM role and are not inconsistent with our limited evidence. The assessment indicates that this system would need Hen House and/or Dog House target tracking data to function most effectively. Assuming that such data were available, the system may be capable of exoatmospheric intercept of incoming ballistic missiles at distances out to about 200 n.m. We believe a nuclear warhead for this system might have a kill radius of up to 30 n.m. against unhardened RVs. Some of the Tallinn system complexes are so located that presently known Hen House or Dog House radars could not furnish useful target tracking data to them. Where this is the case, or if the Hen Houses and Dog House were destroyed or blacked out, the capabilities of the system would be seriously reduced and limited to local and self defense. Thus, under these assumptions, if Hen House or Dog House data were available, the Tallinn complexes could defend areas large enough to provide a strategic ABM defense; without such data, they could not."

In a dissent, Lt. Gen. Joseph F. Carroll, Director, DIA; Maj. Gen. Chester L. Johnson, Acting Assistant Chief of Staff for Intelligence, Department of the Army; and Maj. Gen. Jack E. Thomas, Assistant Chief of Staff, Intelligence, USAF, believed that "the many uncertainties stemming from analysis of available evidence do not support a confident judgment as to whether the mission of the Tallinn-type defensive system is SAM, ABM, or dual purpose. They acknowledge that the available evidence does support a conclusion that these sites may have a defensive mission against the aerodynamic threat. However, on balance, considering all information available, they believe it is more likely that the systems being deployed are for defense against ballistic missiles with an additional capability to defend against high flying supersonic aerodynamic vehicles."

In 1966, members of Congress leaked reports that the Soviets were building an ABM system, the so-called Tallinn Line. Late in November, Secretary McNamara noted that the Soviets had accelerated their ICBM deployments, definitely begun building an ABM system around Moscow and perhaps started a second one, dubbed the Tallinn Line, in the northwestern USSR that featured improved anti-air and perhaps ABM potential.15 Still, Secretary McNamara opposed deploying an anti-Soviet ABM system “at this time.”

Hanson Baldwin reported in the New York Times on 05 Febraury 1967 that "The Tallinn radar is regarded by some experts as too cruse for use against ballistic missiles. However, thefact that the iniital deployment of the Tallinn System covered the most important missile approaches to the Soviet heartland from the United States is though tot be more than a coincidence.

"There is considerable speculation about the installations east of the Urals. Some think the rift with China may have motivated their deployment; others thing these sites might be intended to guard against as United States land-based missile fired the wrong way, or above the Southern Hemisphere and the Southern polar regions towards Soviet targets rather than by the shortest route across the North Atlantic."

In a 14 March 1967 meeting of the Committee of Principals, Secretary McNamara claimed that the current US superiority (such as it was) could not be turned to political advantage. He reasoned that the US lead had come about inadvertently, through an over-estimate of Soviet aims. Now, probably, the Soviets were responding to their own overly pessimistic assessment of American intentions. A good test, National Security Adviser Walt Rostow observed, would be “whether we can establish what the Tallinn system is”—anti-aircraft or anti-missile. General Wheeler thought it “inconceivable that the Soviets did not know where they were going on ABMs,” but Secretary McNamara believed the odds were “ten to one” that they had not yet decided.

Richard J. Whalen, then with the Georgetown University Center for Strategic Studies, wrote in Fortune magazine, 01 June 1967, "A quite different type of installation has appeared in an arc extending several hundred miles along the northwestern border of the country, and this is the focus of disagreement within the U.S. Known as the "Tallinn line" after the Estonian city where one of the defensive sites has been detected, this deployment has been subject to various interpretations: as an advanced anti-aircraft system, another type of ABM, or perhaps a combination of both. Existing Soviet SAM-2's and SAM-3's would seem to provide ample defense against aircraft, particularly in view of the declining U.S. reliance on bombers. Moreover, the line sits athwart the principal "threat corridor" of land-based missiles launched over the North Pole from the US. It is the unanimous judgment of the Joint Chiefs of Staff that the Tallinn line is an anti-missile system, but McNamara so far re- mains publicly unpersuaded.

"In addition to the Moscow and Tallinn deployments, informed sources report a great deal of activity elsewhere in the Soviet Union at existing anti-aircraft installations and new sites as well. Some of these sites are in the South and may represent the early stages of defenses directed against Polaris missiles launched from U.S. submarines on station in the ·Mediterranean. Other sites spotted east of the Ural Mountains face Red China. The small tracking radars along the Tallinn line apparently are tied together with the phased array radar at Moscow.

"As evidence of such links accumulates, the likely scope of Soviet ABM plans expands, confirming McNamara's statement to Congress last January: " ... we must, for the time being, plan our forces on the assumption that they will have deployed some sort of an ABM system around their major cities by the early 1970's." Not only the cities, of course, would be defended, but also military installations, particularly hardened offensive missile silos within a vast territory....

"Estimates of Galosh's range cluster around a few hundred miles, comparable to the Spartan missile the U.S. is now developing. But a minority opinion maintains it could have a much longer range, perhaps as much as 2,000 miles.

"This minority view begins with the fact that the best antiballistic-missile system the U.S. has been able to devise uses two missiles and several types of radar. It is suggesterl that Galosh, the only missile deployed at Moscow, may combine the long range of Spartan with the high acceleration of Sprint, the companion short-range interceptor of the Nike-X system. If this is the case, or if the missile used in the Tallinn line has such a performance capability, the Soviet Union could engage incoming ICBM's far away from their territory and above the atmosphere where fallout would not be a problem-in mid-course of the missiles' trajectory, before multiple warheads and penetration aids could separate. An effective mid-course ABM would provide a formidable defense against multiple warheads.

"An experienced defense scientist cautions against overdrawing Soviet capabilities from scant information ("generalizing from th.e heel of the dinosaur"), but he adds: "If you're honest, you can't say flatly that the Soviets can't do what some people say they are doing. We just don't know"."

When the Committee of Principals reconvened on 22 August 1967, it considered a completed basic arms control negotiations position paper, and made one amendment: Seek assurance that the Tallinn Line would not be upgraded to an ABM system. If that proved impossible, Tallinn launchers must be limited and included in the level of Soviet ABMs.

Despite the opposition of McNamara and many advisors, the pressures increased on Johnson to build an ABM system in response to the Tallinn Line. The Army claimed that their planned Nike-X system would work well as a U.S. ABM system and that it could be deployed at a cost of $8.5 to $10 billion. This investment, the Army claimed, would protect 25 American cities.

American intelligence agencies debated whether the Tallinn Line was actually an anti-missile system. Analysts within the CIA believed the Soviets had built an anti-bomber defense system, while the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) reported that the Tallinn Line would strike at incoming missiles as an ABM system. Both agencies correctly understood that the Galosh system deployed around Moscow consisted of a Nike-type anti-missile system, and if the DIA view of the Tallinn Line were correct, it would mean the Soviets already had two ABM systems (Galosh System and Tallinn Line System).

By the 1970s, SA-5 long-range antiaircraft missiles were installed on the Tallinn Line along the Gulf of Finland.

Upgrading SAM's to ABM's was a potentially serious violation not detectable without very high resolution photography. US estimate of the SA-5 (TALLINN) missile could have been made with greater confidence 5 years sooner with very high resolution photography. A key element in identification of a defense system such as the SA-5 is analysis of associated electronic systems. The role of BEER CAN radar, originally associated with Leningrad ABM complex, was never defined because of lack of detail on feed structure. By 1970 radars associated with SA-5 had still not been photographed with resolution adequate for analysis and evaluation.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|