Battle of the Atlantic

The war was in one sense lost before it began, because Germany was never prepared for a naval war against England. The possibility of having England as an antagonist was not envisaged until 1938, because the government was ill-advised politically. Hitler had never been abroad. A realistic policy would have given Germany a thousand U-boats at the beginning of the war.

When Adolf Hitler assumed power on 30 January 1933, the German Wehrmacht found itself in a position of impotency. The strength of the German Army was 100,000 men. There was no German Air Force. The navy had not yet attained even the strength allowed it in the Versailles Treaty, having only a total strength of 15,000 men. There were 6 new light cruisers, each of 6,000 tons, available. The torpedo boats had been brought up to the permitted number of 24 by the construction of 12 new ships. Of the pocket battleships of the Deutschland class, only one ship, the Deutschland itself, had been completed. Two more, the Scheer and the Graf Spee, were building; but the three other pocket battleships which could have been built under the treaty had not yet been ordered.

Hitler was striving for a political agreement with England, having always regarded Bolshevik Russia as the arch enemy of Germany. This policy of Hitler found its consummation in 1935 with the conclusion of the naval agreement with England, which fixed the strength of the German Fleet at 35 percent of the English (U-boats at 50 percent).

England was in every respect dependent on sea-borne supply for food and import of raw materials, as well as for development of every type of military power. The single task of the German Navy was, therefore, to interrupt or cut these sea communications. It was clear that this object could never be obtained by building a fleet to fight the English Fleet and in this way win the sea communications. The only remaining method was to attack sea communications quickly. For this purpose only the U-boat could be considered, as only this weapon could penetrate into the main areas of English sea communications in spite of English sea supremacy on the surface.

Therefore, when the war with England became an actuality in September 1939, a considerably increased U-boat construction program was ordered. Whereas previously the monthly output was only about 2 to 4 U-boats, in the new U-boat construction program ordered in September 1939, it was intended to reach by stages 20 to 25 U-boats a month.

The Battle of the Atlantic pitted the German submarine force and surface units against the U.S. Navy, U.S. Coast Guard, Royal Navy, Royal Canadian Navy, and Allied merchant convoys. The convoys were essential to the British and Soviet war efforts, and, later, supported the build-up and sustainment of U.S. forces in the European theater of operations.

The Germans faced a gross lack of U-boats at the start of the war due to faulty political concepts of the Third Reich. Then the naval construction program was relegated to a role secondary to the development of the Luftwaffe, resulting in failure of the German Navy ever to obtain any semblance of surface superiority; and this lack of naval strength was definitely one of the primary causes of "postponing" the invasion of England.

The naval staff and the U-boat command had expected great results from the use of U-boats in the Norway invasion in April 1940, but the result of the U-boat activity was extraordinarily disappointing. The chief reason for this was torpedo failures. If a torpedo shortage had been evident in the early months of the war, it was now torpedo ineffectiveness in the Norwegian expedition which became disastrously apparent. The effect on the crews was marked. They lost confidence in the weapon, and the personal influence of the U-boat commander in chief was necessary to restore their morale.

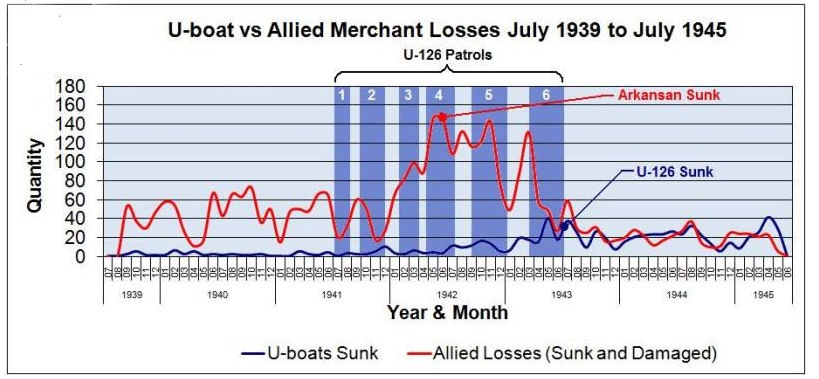

During the entire World War II, the submarine/anti-submarine warfare between the Allies and the Germans was roughly divided into three phases: the first phase was from October 1939 to December 1941. The battle at this stage was mainly between the British and German forces. The war situation can be described as the extensive use of the escort system in the UK, but the number of ships is insufficient and there are a large number of loopholes in the escort system. However, due to the lack of German submarines, the actual losses of the British army were also limited. Very soon after the beginning of the war the convoy system was instituted by England to an ever increasing degree. By this, merchant ships lost the protection of all international rules, as under the protection of their own warships they had put themselves outside the prize law. The U-boats were then given freedom of attack on all merchant ships escorted by enemy warships.

The first convoy attacks at the end of October 1940 succeeded with very good results. In these engagements the U-boats quickly exhausted their torpedoes. Success of wolf-pack tactics was dependent upon reconnaissance to locate convoys. Aircraft was the logical instrument for the accomplishment of this mission, but the navy was dependent on the Luftwaffe for air support. Eventually sufficient pressure was exerted so that a squadron of FW200's was placed at the disposal of the U-boat command in September 1940. However, results proved to be painfully slow. Owing to the limited range of the aircraft it was only practicable to operate on the England-Gibraltar convoy routes. The main shipping routes in the North Atlantic had to be reconnoitered by the U-boats alone.

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, was a complete surprise to Germany's political and military leaders. It also resulted in a state of war between the United States of America and Germany. Conditions for U-boat warfare in the North Atlantic were once again clarified. Limiting factors vis-a-vis North America ceased to operate. The bar against German U-boats entering American waters was raised by the political leaders and in December the U-boat command equipped the first six U-boats which were to operate in American waters as near to the coast as possible.

The second stage was from January 1942 to March 1943. At this time, the US military had little experience in combating anti-submarine warfare. Therefore, even though the number of ships was large, the implementation of the patrol system was early in the war, so a large number of American merchant ships became the lamb to be slaughtered. Once contact was made with the convoy the attack succeeded every time. The difficulty lay in the finding and not in the attacking. Depth-charge attacks by destroyers against U-boats were not much feared.

In 1942, the German Cypher Office was fortunate enough to read various convoy ciphers. The German U-boat command thus had at its disposal the place and time of convoy meetings and also gathering points for convoy stragglers. This valuable assistance to attacking U-boats ceased in the early months of 1943.

One German anxiety at that time was the possibility of the development of surface detection. Possible available counters included protection for U-boats on the surface against radar beams. The U-boat was enabled, as it were, to assume a cloak of invisibility. During the following years the most varied experiments were carried out in this direction. They led to a clear recognition that, at the most, reduced but not total absorption of radar beams could be achieved.

Despite the greater successes achieved in 1942 with mounting numbers of boats, the effectiveness of the individual boats was actually small compared with the year 1940. The proportion of the average tonnage sunk by each U-boat each day in 1942 was only about one-tenth of that in 1940. In March 1943, conditions on the main battleground, the North Atlantic, were again very favorable. Many convoys were met and attacked with very great success. The most successful convoy battles and also the attacks on the convoys by the commanding officers reached their peak.

The U-boat commanders were men who, through years of seafaring in wartime, felt at home in the Atlantic in both summer and winter, and were a group of bold seamen of outstanding fighting ability. Consequently, there were convoy battles in which more than half, and in some cases over two-thirds, of the convoy was wiped out.

The radius of action of all the boats was considerably extended by the use of supply U-boats, from each of which, about 10 U-boats could each draw 40 tons of oil and additional provisions, thus obviating the unnecessary voyage to and from even the Biscay ports. The U-boats also fueled by surface tankers when such were available. These could also supply torpedoes.

After the winter of 1942 had produced changes in the situation in Russia and in the Mediterranean unfavorable to Germany, there appeared in the spring of 1943 a similar change in the U-boat warfare which was, however, quite independent of the former and due to completely different causes. by May 1943 it was quite clear that the enemy's air strength in the Atlantic, consisting of long-range planes and of carrier-borne aircraft, had increased enormously. Of even greater consequence, however, was the fact that the U-boats could be located at a great distance by the enemy's radar. The U-boat losses, which previously had been 13 percent of all the boats at sea, rose rapidly to 30 to 50 percent. In 1943 alone, 43 U-boats were lost. These losses were suffered not only in convoy attacks, but everywhere at sea.

It was finally clear that surface warfare for U-boats had come to an end. The Schnorckel was being developed for all types to enable the boats to recharge under water. The Schnorckel was not yet ready as its use necessitated alterations to the Diesel, and extensive trials had to be made in order that its use at sea should not endanger the crew. The boats fitted with Schnorckel did not need to surface at all and the losses dropped suddenly by more than half. By the end of 1944 practically all available old type U-boats on operational work had been fitted with Schnorckel.

The loss of France was a set-back of utmost gravity for the conduct of the war at sea. All the strategic advantages arising from the possession of the Biscay ports were lost with one blow. The U-boats had to fall back on the Norwegian and home bases. The long passage swallowed up a disproportionately great part of the boats' endurance and had to be made submerged. From the winter of 1944 until the end of the war more U-boats already in commission in German waters were being lost by bombing than were lost at sea.

In March 1945 several Type XXIII boats were for the first time sent to operate on the English east coast. This operation confirmed the hopes entertained. Out of seven trips five were successful. All boats returned to base in spite of the strongest opposition. By virtue of their high speed submerged, the boats came easily to the attack and thereafter withdrew from enemy countermeasures by making off at high speed. The personnel had great confidence in the new type. This applied equally to Type XXI.

This new effectiveness of the German U-boat war was cut short by the German capitulation which had become inevitable through the occupation by the enemy of the whole German area.

The huge volume of the United States shipbuilding in the early 1940s actually offset the German victories, so the actual loss of the Allies was not unbearable. In other words, even if the power gap between the two sides is not disparity, the submarine warfare was not useful in the face of a good escort system. This is because the surface ships still have enough means to deal with the threat of submarines. Submarine/anti-submarine warfare mainly consists of two large components: the enemy and the attack. In terms of target search, both sides rely on visual, immature sonar and more mature radar, and the offensive and defensive means are basically equal; in terms of attack, the submarine's torpedo has a long range but easy to evade, while the surface ship's deep bullet and hedgehog Weapons such as guns have a relatively close range.

As for the problem of anti-submarine aircraft carriers, the escort carriers were late and their number was small. The “jeep carriers” or “baby flattops” were often built using merchant ship hulls. They were typically half the length and had a third of the displacement of larger fleet carriers, and were also slower, carried fewer planes, and were less well armed and armored than these. However CVEs were cheaper and could be built quickly. They were ideally suited to provide continuous air cover for slow-moving merchant convoys. Later in the war, escort carriers also formed part of antisubmarine hunter-killer groups.

The lack of an adequate naval air arm was a result of Hitler's decision to form the flying units required for the navy within the framework of the Luftwaffe. The German Navy was equipped with seaplanes and flying boats. This proved, during the course of the war, to be a mistake. The high performances - notably long range - required could not be obtained from the seaplane types. This proved a decisive disadvantage in the German conduct of the war at sea, and conversely the outcome of the U-boat war in 1941 would have been quite different if the navy had had its own air arm.

Had the political leaders before the war recognized England as a probable opponent, and had they in 1937 prepared for a war with England and constructed a large U-boat fleet, the number of U-boats available in 1942 would have been available in 1940 but with 10 times greater results. The political desire of Germany's leaders not to make war against England and the corresponding armament policy of the navy led to Germany not having the requisite U-boats available at the right time or in the right numbers.

The ultimate cost of victory in this vast area of operations was sobering: Between 1939 and 1945, 3,500 Allied merchant ships (14.5 million gross tons) and 175 Allied warships were sunk, and 72,200 Allied naval and merchant seamen lost their lives. The Germans lost 783 U-boats and approximately 30,000 sailors, three quarters of Germany's 40,000-man submarine force.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|