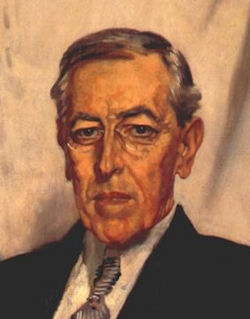

Woodrow Wilson (1913-1921)

A native of Virginia, Woodrow Wilson was the first Democrat elected to the White House since the election of James Buchanan in 1856. His election was only made possible by a split in the Republican Party between the two previous Republican Presidents [Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft], and marked a brief interruption of Republican possession of the White House from 1861 to 1933.

A native of Virginia, Woodrow Wilson was the first Democrat elected to the White House since the election of James Buchanan in 1856. His election was only made possible by a split in the Republican Party between the two previous Republican Presidents [Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft], and marked a brief interruption of Republican possession of the White House from 1861 to 1933.

President Wilson considered himself the steward of the people. Toward that end, he proposed a reform-oriented "New Freedom" domestic program, but he soon faced serious international problems. During his second term, he abandoned neutrality in World War I, but then led the United States into the conflict on a crusade to "make the world safe for democracy," and figured prominently in the peacemaking. Yet the Senate refused to ratify the Treaty of Versailles, which included provisions for a League of Nations. And Wilson, afflicted with a stroke, was incapacitated for his last 17 months in office.

The eldest son and third child in a family of four, (Thomas) Woodrow Wilson was born in 1856 at the manse of the First Presbyterian Church, Staunton, Va., where his father was a Presbyterian minister. The family lived in the South through the Civil War and Reconstruction. During Woodrow's boyhood, Reverend Wilson held several posts in the South. Shortly after the youth's first birthday, the family moved to Augusta, Ga. In 1870 his father began teaching at a seminary in Columbia, SC, and for the next few years also held a nearby pastorate. Parents, tutors, and local schools provided Woodrow with his early education.

In 1873 Wilson matriculated at Davidson (N.C.) College, a small Presbyterian institution. The following year, illness forced him to rejoin his family at their new home in Wilmington, N.C. He next won a B.A. at the College of New Jersey (present Princeton University), which he attended during the period 1875-79. He was not only a serious student, but also an able orator and debater. Upon graduation, Wilson entered the University of Virginia Law School. Late in 1880, however, ill health once again forced him to go back to Wilmington, where he carried on his study. In 1882 he received his degree, was admitted to the Georgia bar, and set up a law practice with a friend in Atlanta. Before long, however, he lost interest in the profession.

In the fall of 1883, Wilson enrolled at the graduate school of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Two years later, his first book, Congressional Government, was published. That same year, he married Ellen L. Axson, daughter of a Presbyterian minister. She was to bear three daughters.

From 1885 until 1888, Wilson held a professorship of history at Bryn Mawr (Pa.) College. During this time, in 1886, he won his Ph. D. in political science from Johns Hopkins. He next taught history and political economy (1888-90) at Wesleyan University, Middletown, Conn. He then became professor of jurisprudence and political economy at the College of New Jersey (Princeton University after 1896). By 1902, he had authored nine books and 32 articles. During the interim, he had refused three offers of the University of Virginia presidency.

In 1902 Princeton's board of trustees unanimously chose Wilson as president. His fight to "democratize" the institution met with opposition from many faculty and alumni, but brought him some national recognition and encouraged an interest in politics. In 1907 State Democratic leaders considered him as a U.S. Senate nominee, but he withdrew after reformers attacked him as a machine spokesman. Identifying himself with moderate progressivism, in the fall of 1909 Wilson was elected as head of the Short Ballot Association, a national organization dedicated to improving local government. Further broadening his reputation, he also began to speak out against trusts and high Republican-inspired tariffs.

In 1910 Wilson resigned from Princeton to become the Democratic gubernatorial candidate. Asserting his independence of party leaders and refusing to make patronage pledges, he campaigned as a reformer and won election by a wide margin. The Democrats also won enough votes to control the legislature. Wilson blocked the legislative selection of a party-backed candidate to the U.S. Senate, and pushed through significant measures. Included were those dealing with direct primary and other election reforms, regulation of utilities, pure food protection, woman and child labor restrictions, and employers' liability. When Republicans took over the legislature in 1912, Wilson refused to compromise and vetoed 57 bills.

In pursuit of the Presidential nomination, late in 1911 Wilson began a nationwide series of speeches. The national convention deadlocked the next year and nominated him on the 46th ballot. He then stumped the country and expounded his "New Freedom." This program emphasized restoration of the Government to the people through control of special-privilege groups by the initiation of various reforms, especially in the fields of tariff revision and the regulation of trusts and banks. Benefiting from the split between Republican William Howard Taft and Progressive Theodore Roosevelt, Wilson won only 42 percent of the popular vote but carried 40 of the 48 States.

As President, Wilson felt he needed to exert strong leadership to fulfill his self-conceived role as a direct representative of the people. He became the first Chief Executive since John Adams to address joint congressional sessions; inaugurated regularly scheduled press conferences; championed substantially lowered rates in the Underwood Tariff (1913), which included the first constitutional Federal income tax; fought for the Federal Reserve Act (1913) to stabilize and regulate currency through regional governmental banks controlled by a board of Presidential appointees; established the Federal Trade Commission (1914) to prevent unfair business practices; strengthened antitrust legislation; and recognized the legality of labor unions and their right to strike.

Judson MacLaury, U.S. Department of Labor Historian, wrote in 2000 that "During the 1912 presidential campaign Wilson, a progressive Southern Democrat, had encouraged Negro support with vague promises to be "President of the whole nation" and to provide Negroes with "absolute fair dealing." He specifically promised that he would at least match past Republican appointments of Negroes to patronage positions. The NAACP endorsed Wilson and Negro groups worked vigorously for his election. Wilson's victory was mainly attributable to the Taft-Roosevelt split and the Negro vote was not decisive. Yet Negroes were proud of their involvement in the campaign and, heartened by the idealism of Wilson's inaugural address, looked forward to turning vague campaign promises into concrete advances for working Negroes and the whole race."

In 1914 Wilson's wife died. The next year, he married widow Edith Bolling Galt. The couple had no children.

Wilson had not been in office too long before Latin American and European affairs captured his attention. In 1914, after incidents at Tampico and Veracruz, Mexico, he sent in troops that captured the latter city, but mediators prevented the outbreak of a full-scale war. Two years later, he dispatched a military expedition into Mexico in retaliation against raids that revolutionary Pancho Villa had made into Texas and New Mexico.

In the Caribbean, Wilson continued the traditional American role of intervention. Mainly to quell revolutionary strife and protect U.S. interests, in 1915 and 1916 he deployed military forces to Haiti and the Dominican Republic, respectively, and established virtual protectorates. In 1917 he acquired the Virgin Islands from Denmark.

The situation in Europe was far more serious. After the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Wilson proclaimed U.S. neutrality. It proved to be difficult to maintain. The President protested to Great Britain over her blockade against nonbelligerent maritime trade. But Germany's actions were even more alarming. To halt the flow of materiel to France and Britain, beginning early in 1915 her submarines (U-boats) sank neutral ships without warning. Wilson's complaints went unheeded. After the sinking of the Lusitania, a British liner carrying many Americans, Wilson further protested and Germany relented. Following another similar episode, in the spring of 1916 he threatened to break off diplomatic relations and Germany again backed down.

During the 1916 election campaign, defending his domestic program and employing the slogan "He kept us out of war," Wilson eked out a narrow victory in the electoral college over Republican Charles Evans Hughes.

In an attempt at mediation, early in 1917 Wilson proposed to the European powers a "peace without victory" plan that he felt would insure a just and equitable end to the conflict, but both sides were reluctant to negotiate. Meantime, most Americans had become convinced that Germany and her allies were the aggressors. Events soon underscored this position. The Germans launched an unrestricted submarine offensive in late January 1917 on the gamble that it would crush the Allies before the expected United States entry could affect the outcome.

After Wilson severed diplomatic relations the next month anti-German feeling in the country increased because of the publication of the Zimmermann Note, a secret proposal for an alliance of Mexico, Japan, and Germany against the United States. Following the sinking of more American vessels, in April 1917 Congress declared war. Wilson, who viewed it as a moral crusade to preserve freedom and democracy against German autocracy, directed the mobilization of the Armed Forces and the production of military materiel that helped bring Allied victory in November 1918.

Earlier that same year, distressed by Bolshevik, or Red (Communist), advances in the Russian civil war among other reasons, Wilson had supported Allied military intervention to aid pro-democratic Russians. It lasted until 1920.

The World War I armistice was partly based on Wilson's "Fourteen Points," which he had proposed early in 1918 as the basis for a lasting peace. Applauded by many Europeans, late that same year Wilson and his mostly Democratic delegation arrived at the Paris Peace Conference. Although he was forced to compromise on parts of his plan, he obtained European commitments to a League of Nations, which he trusted would resolve future international differences. Provisions for the league were incorporated into the Treaty of Versailles. These efforts were to win Wilson the Nobel Peace Prize in 1919.

When Wilson returned to Washington, DC in the summer of 1919, he presented the treaty to the Senate for ratification. The Republicans took over control of the Senate in 1918, when the end of the war produced a new wave of isolationist sentiment, but Wilson refused to compromise. He insisted that the treaty, and the League of Nations at its heart, be accepted without change. In September, he launched a "whistle-stop" tour to build public support for ratification, against the advice of his doctor. Wilson was a spellbinding speaker, and some people think he might have succeeded, but on October 2, 1919, he collapsed from a paralytic stroke. The Versailles Treaty failed in the Senate by seven votes. It took until the Harding administration to pass a joint congressional resolution formally ending the war.

Wilson's uncompromising stance was not the only reason for the Senate's lack of cooperation. Also involved were partisanship and the return of isolationist sentiment.

After the October 1919 a stroke incapacitated Wilson, he remained under the protective care of his wife until Harding took over the reins of Government in March 1921. Some historians call her "the first female president of the United States" for the role she played in hiding the effects of her husband’s disabling illness from the public during his last year and a half in office. During retirement, Wilson never recovered his health. His wife ministered to him at their recently purchased home in Washington, DC. Although he joined a law firm, he never practiced. He died in 1924.

The 2024 book "Woodrow Wilson: The Light Withdrawn" by Christopher Cox reassessed his life and his role in the movements for racial equality and women’s suffrage. Over two thousand books had already been written in English about Woodrow Wilson. The Wilson that emerges is a man superbly unsuited to the moment when he ascended to the presidency in 1912, as the struggle for women’s voting rights in America reached the tipping point. The first southern Democrat to occupy the White House since the Civil War era brought with him to Washington like-minded men who quickly set to work segregating the federal government. Wilson’s own sympathy for Jim Crow and states’ rights animated his years-long hostility to the Susan B. Anthony Amendment, which promised universal suffrage backed by federal enforcement. Women demonstrating for voting rights found themselves demonized in government propaganda, beaten and starved while illegally imprisoned, and even confined to the insane asylum. When, in the twilight of his second term, two-thirds of Congress stood on the threshold of passing the Anthony Amendment, Wilson abruptly switched his position. But in sympathy with like-minded southern Democrats, he acquiesced in a “race rider” that would protect Jim Crow.

Wilson segregated Washington, DC. Any Democrat elected in 1912 would have done the same due to the Southern political base of the Democratic Party at the time. But not a single one of the three Republicans who followed him desegregated. It was partly desegregated with a push from Eleanor Roosevelt but not fully desegregated until 1954.

Wilson naturally held Victorian views of women and their roles in his youth, to be expected of someone born in 1856 Staunton, Virginia. He held certain chauvinistic (Wilson would have argued chivalrous) views of women. Wilson grew and changed his views and that leaders of the Suffrage movement credited him with the key to making votes for women happen. One quote from a leading Suffragist is from when Wilson made his first public endorsement. Alice Paul told reporters shortly after his first public endorsement of the federal amendment in January 1918, "It is difficult to express our gratification at the President's stand. We knew that it, and perhaps it alone, would ensure our success. It means to us only one thing - victory.

And Cox’s account of The Birth of a Nation screening in the White House is "so provably wrong and one-sided as to suggest he has only skimmed through biased secondary sources". He seems to have taken D W Griffith and Thomas Dixon's statements at face value. Witnesses of the event at the White House observed that Wilson was not amused by the film, left early after wadding up his program, and prepared a rebuttal stating that he did not endorse the movie. The most famous quotation, supposedly by Wilson, did not appear until after his death. Wilson historian Mark Benbow did a full, well-researched analysis of this. If someone wants to know the history of that event, they should read Mark Benbow’s Birth of a Quotation.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|