Japanese Anti-Aircraft Artillery [AAA]

Tai-Ku Ko-Sha Ho Hei

Anti-Aircraft High-Angle Gun Troops

| Anti-Aircraft Artillery KoKaku Ho/ High-Angle Gun | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| year | type | caliber | built | |

| 1938 | Type 98 | 20-mm | 2,500 | |

| 1942 | Type 2 | 20-mm | ? | |

| 1942 | Type 4 | twin-mount | 20-mm | 500 |

| 1936 | Type 96 | 25-mm | 33,000 | |

| 1922 | Type 11 | 75-mm | 44 | |

| 1928 | Type 88 | 75-mm | ? | |

| 1938 | Type 4 | 75-mm | 70 | |

| 1938 | Type 99 | 88-mm | ? | |

| 1938 | Type 98 | naval AAA | 100-mm | 68 |

| 1925 | Type 14 | 105-mm | ? | |

| 1914 | Type 3 | naval AAA | 120-mm | ? |

| 1929 | Type 89 | naval AAA dual | 127-mm | ? |

| 1945 | Type 5 | 150-mm | 2 | |

| Anti-Aircraft Surface to Air Missiles | ||||

| 1945 | Funryu-2 | -mm | 0 | |

| 1945 | Funryu-4 | -mm | 0 | |

Japanese Antiaircraft Artillery [AAA] lagged behind the other major powers throughout the war. The Japanese lacked the technological and manufacturing base to deal with their air defense problems and to make good their deficiencies. In addition, the Japanese received only limited assistance from the Germans and failed to fully mobilize their civilian scientists.

Japanese Antiaircraft Artillery [AAA] lagged behind the other major powers throughout the war. The Japanese lacked the technological and manufacturing base to deal with their air defense problems and to make good their deficiencies. In addition, the Japanese received only limited assistance from the Germans and failed to fully mobilize their civilian scientists.

Japan's air defense had never been first-class. Between the fighter squadrons of the army and navy of Japan, there was never close interaction, its radar system and early warning system were imperfect, although they were equipped with almost all modern equipment, including radar stations, radiotelephone and radiotelegraph communications. In addition, the early warning system included a group of patrol ships that performed the task of detecting enemy aircraft on the distant approaches to the coast, which would be advisable to use in the modern US early warning system.

When organizing the air defense of the territory of Japan, the ground forces command proceeded from the following: the first line of defense of Japan in the war with the Soviet Union should pass near the continent, since Soviet aircraft could launch air raids on Japanese objects using air bases in the r. Ussuri. The organizational structure of the troops, their weapons and military equipment, military use, education and training, the nature of scientific research in the field of technology and military art - all based on this idea.

Until 1944, the Imperial Japanese Army was slow in deploying strategic anti-aircraft defense, with the formation of the first anti-aircraft regiment in 1924, and the deployment of only four regiments in 1939. This complacency came from the lack of serious threats from neighboring China and the Soviet Union, as well as from the belief that fighter aircraft was the best alternative. The outbreak of the Pacific War in December 1941 led to a general expansion of the IJA, with anti-aircraft artillery as a branch of field artillery, increasing almost sixfold from about 12,500 soldiers in 1939 to 68,500 in 1941. Air defense units were locally organized under the General Department of Defense and military districts.

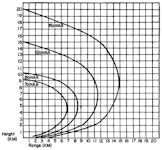

The most widely used Japanese heavy flak piece was the 75mm Type-88 that entered service in 1928. It fired a 14.5-pound shell at a muzzle velocity of 2,360 fps to 23,550 feet but was inaccurate above 16,000 feet. The Japanese stuck with this gun throughout the war, while the Americans, British, and Germans went to larger and better performing weapons.

Not that the Japanese did not try to upgrade their weapons they produced an improved 75 mm gun (75 mm type 4) in 1944 but built only 65 and got few into action. Likewise, the Japanese put a 120 mm gun into production in 1943 but built only 154. Only two 150 mm guns saw service. The Japanese also used a few 88 mm naval guns.

In 1941, the Japanese deployed 300 antiaircraft guns in defense of the home islands. By March 1945, they deployed 1,250, and, by the end of the war, over 2,000. As might be expected, the Japanese concentrated the largest number of their heavy guns (in all 509 to 551) around Tokyo: in August 1945, 150 naval 88 mm guns; 72 120 mm guns; and two 150 mm guns. Thus, compared with the Germans, the Japanese deployed fewer and less-capable guns. In addition, Japanese radar was far behind German radar. The Japanese did not capitalize on German technology but primarily relied on technology from captured American and British equipment.

Japanese flak proved less effective than the firepower of the other combatants. Based on overall losses and losses per sortie, the air war against Germany was much more costly to the AAF (18,418 aircraft and 1.26 percent of sorties) than the air war against Japan (4,530 aircraft and 0.77 percent of sorties). In the entire war, the AAF credited Japanese flak with destroying 1,524 AAF aircraft and Japanese fighters with destroying 1,037. Japanese AAA did better proportionally against the US Navy than against the US Marine Corps, claiming 1,545 of 2,166 Navy aircraft lost in combat as compared with 437 of 723 Marine aircraft.

The AAF lost 414 B-29s in combat against Japan. They estimated that 74 fell to enemy aircraft, 54 to flak, and 19 to both flak and fighters. The ineffectiveness of Japanese flak and electronics is highlighted by the American decision to change from their prewar bombing doctrine and European strategic bombing practice of high-altitude day attacks to night attacks below 10,000 feet.

Unlike the campaign against Germany that was dominated by the battle against GAF fighters, this decision resulted from poor bombing results, not aircraft losses. Consequently, the B-29s attacked Tokyo at low altitudes at night and suffered slightly fewer casualties: 39 aircraft on 1,199 sorties (3.2 percent) at night compared with 35 bombers lost on 814 sorties (4.3 percent) on daylight high-altitude missions. At the same time, bombing effectiveness greatly increased.

The limited number of Japanese guns and primitive electronics encouraged the AAF to fly at lower altitudes with heavier bomb loads, where it achieved greater accuracy and encountered fewer mechanical problems than had been the case earlier at higher altitudes. The American Airmen went on to burn out Japanese cities and towns with conventional weapons. The reduced and bearable attrition resulted from Japanese flak deficiencies and employment of such American measures as saturating the searchlight defenses, ECM, desynchronizing the propellers of the bombers to inhibit Japanese sound-controlled searchlights, and use of high-gloss black paint.

The rate of B-29 losses to flak and flak plus fighters decreased steadily after peaking in January 1945 at 1.06 percent of sorties. Tokyo was the most bombed (4,300 of 26,000 sorties) and the best defended of the Japanese targets. Its defenses accounted for 25 of the 55 flak losses of the Twentieth Air Force and for 14 of its 28 losses to flak plus fighters. As would be expected, American losses were much lighter at the less-defended targets. Specifically, in flying 4,776 night sorties at low and medium altitudes against major Japanese cities, the Twentieth Air Force lost 83 bombers (1.8 percent) as compared with seven lost (0.1 percent) under similar conditions against secondary cities.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|