Taklamakan Desert, Tarim Basin, Xinjiang

Based on recent satellite imagery, the Chinese military has built several models of US warships in the Xinjiang desert. The US Naval Institute (a nonprofit organization) cited information from the intelligence company All Source Analysis reported 08 November 2021 that satellite imagery show a full-scale simulation of an aircraft carrier and at least two Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyers of the US Navy, built in a military complex in the Taklamakan Desert, Xinjiang. This reflects China's efforts to increase combat training against aircraft carriers, especially US Navy ships, amid Beijing's recent high tensions with Washington over the Taiwan and the South China Sea, according to Reuters. It is known that China's anti-ship ballistic missile units are currently in the service of the People's Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF). A satellite image released by US space technology company Maxar Technologies on 07 November 2021 revealed that the figure in the shape of a full-scale U.S. warship may be used as a target for attack training against the most powerful units of warships dispatched to the Pacific Ocean.

Based on recent satellite imagery, the Chinese military has built several models of US warships in the Xinjiang desert. The US Naval Institute (a nonprofit organization) cited information from the intelligence company All Source Analysis reported 08 November 2021 that satellite imagery show a full-scale simulation of an aircraft carrier and at least two Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyers of the US Navy, built in a military complex in the Taklamakan Desert, Xinjiang. This reflects China's efforts to increase combat training against aircraft carriers, especially US Navy ships, amid Beijing's recent high tensions with Washington over the Taiwan and the South China Sea, according to Reuters. It is known that China's anti-ship ballistic missile units are currently in the service of the People's Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF). A satellite image released by US space technology company Maxar Technologies on 07 November 2021 revealed that the figure in the shape of a full-scale U.S. warship may be used as a target for attack training against the most powerful units of warships dispatched to the Pacific Ocean.

According to a report by the U.S. Navy Institute (USNI), analysis of past satellite images showed that "aircraft carrier targets were installed in March-April 2019" and then "mostly dismantled in December of the same year. However, it was restored in late September this year and was mostly completed in early October." The aircraft carrier model is full-size and should appear on the radar similar to a target image, the report said. It is not the first time that such targets have been built in the desert, but these replicas are more accurate and more developed. USNI also mentions information from information analysis firm AllSource Analysis that the region has been used in ballistic missile experiments in the past. China's Foreign Ministry spokesman Wang Wenbin was asked about the satellite image on the 8th and said he was "not aware of the situation."

China normally states that military exercises "target no particular country". These are surface targets with Chinese Characteristics Under Modern Conditions, and are very un-American since the United States had historically faced a target poor environment. The new generation of ground-to-ground and air-to-ground weapon systems that employ intelligent seekers require ground targets with visual, infrared, acoustic and radar signatures that accurately emulate the real version of the threat. The Army Surface Targets (ST) program is responsible for managing the acquisition and certification of actual threats, as well as development, prototype fabrication and validation of ground target surrogates to meet these requirements.

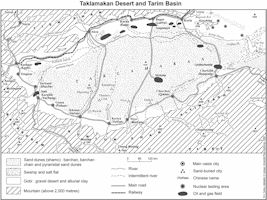

The land of Xinjiang is austere but beautiful, and the great oases that ring the Taklamakan desert are verdant. The Desert of Moving Sands, Takla Makan Desert, Sinkiang; 39° N., 83° E is also known as Pustynya Takla-Makan, Takla-Makan, Taklamakan, Takla Makan Desert, Takla-Makan Desert, Taklamakan Desert, Taklamakan desert, Takla-makan Sai, T'a-k'o-la-ma-k'an Huang-ti, T'a-k'o-la-ma-kan Sha-mo, Wüste Takla-makan. The heart of Mongolia is the great Gobi Desert-Shamo as it is called by the Chinese—that forms the eastern end of a belt of arid land running almost across Asia. The wastes about the Tarim basin belong to the same belt, and are by some writers included in the name of Gobi, by others distinguished as the TaklaMakan Desert. For some thousand miles, with a breadth of 300 to 400 miles, this barren tract, once an Asian Mediterranean, covers a plateau at a mean height of 4000 feet, rising higher on the east side, and here and there sinking into troughs of depression.

Fully 85 percent of the total area, nearly the same size as Finland, consists of mobile, crescent-shaped sand dunes and are virtually devoid of vegetation. The Taklimakan Desert is hemmed in to the north by the snow-covered Tian Shan Mountain range and to the south by the rugged Kunlun Mountains. To the south lies the Karakoram Mountain range, where the world’s second highest mountain, K2, casts a blue shadow. Desertification and shifting sand dunes are a major concern for the farmers and herders who live at the Taklimakan’s edge. This is one of the largest sandy deserts in the world. The desert’s natural conditions are adverse, and there are serious hazards from wind-drift sand. The area is characterized by a dry climate, low rainfall, and high evaporation. There is little variation in color and intensity across the area. The desert has an area about 960 km from west to east, and it has a maximum width of 420 km. The desert has elevations of 1,200 to 1,500 m above sea level in the west and south and from 800 to 1,000 m in the east and north. Takla Makan Desert presents an expanse of loose reddish soil, strewn with pebbles and bones, where only a little thorny and wiry vegetation struggles to life, a dreary prospect, relieved by wave-like hillocks of sand, by rocky islets here and there, by patches of pale scrub, by scums of nitre, and by salt-crusted lakes that, glittering like ice, prove to thirsty travellers a bitterer mockery than the delusive mirage.

The Taklimakan desert fills the expansive Tarim Basin between the Kunlun Mountains and the Tibet Plateau to the south and the Tian Shan Mountains to the north. The Tarim River flows across the basin from west-to-east. In these places, the oases created by fresh surface water support agriculture. By any definition, a desert is a place that is crying for water. Because it is under constant environmental stress, the desert is more fragile than other ecosystems; even small alterations, natural or manmade, can be of considerable consequence. Deserts form in areas of rainshadow, where mountain chains force the ocean air upward, cool it, condense its moisture, and cause rain to fall on the windward side. Crossing the peaks, the air was sucked down. Warm and dry, it drank thirstily from the land. The TaklaMakan Desert in China is one example of deserts caused by the rainshadow effect. To the north the characteristics of this Asian Sahara are encroached on by mountains enclosing large saline lakes. These mountains play the same part as the Himalayas in arresting the moist winds from the ocean, so that their northern sides may be thickly wooded and veined with streams pouring down to the great rivers of Siberia, while the southern slopes are nakedly dry, soon sucking up what rain finds its way beyond the ranges.

Since the 1950s agricultural activity, especially the extremely water intensive production of cotton, has expanded and the population in the oasis cities along the Tarim River has grown considerably. As a consequence, the Tarim River loses water as it flows downstream and the lowest parts of the river’s downstream reaches are completely desiccated due to the extensive exploitation of river water in the upper reaches. The dramatic loss of water resources in the lower reaches has led to a severe deterioration of the highly vulnerable riparian ecosystems, desertification and loss of biodiversity, negatively affecting the living conditions of local people and the development of the entire region. Due to the predicted impacts of climate change, i.e., increasing temperatures, changes in seasonal precipitation and glacier melting, the problem of water shortage will become more and more serious and the effects on the entire region will be disastrous. Worst-case scenarios predict the complete desiccation of the Tarim River leading to a merging of the Taklamakan Desert into the southern part of the Gobi Desert.

The Taklimakan is China's largest, driest, and warmest desert in total area of 338,000km^2 with perimeter of 436 km, it is also known as one of the world's largest shifting-sand deserts. Studies outside Xinjiang indicated that 80% dust source of storms was from farmland. Dust storms in the Tarim Basin occur for 20 to 59 days, mainly in spring every year. The abundant sand provides material for frequent intense dust storms. When a blowing sand or dust storm weather event occurs, the atmospheric vertical velocity tends to be of upward motion. This vertical upward movement of the atmosphere supported with a fast horizontal wind and a dry underlying surface carries dust particles from the ground up to the air to form blown sand or a dust storm. The particle size distributions and their modal parameters such as VMD (volume median diameter) have significant difference for varying dust origins. The dust from Taklimakan desert was finer than that from Gobi desert also probably due to other influencing factors such as mixing between dust and urban emissions.

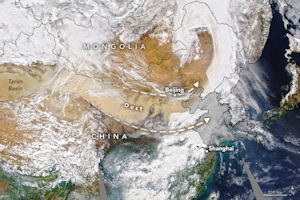

Dust storms commonly occur across Asia in springtime. But in March 2021 meteorological spring was just getting underway, and already an enormous plume of sand and dust has blanketed northern China. It has been called the largest and strongest such storm to strike the region in a decade. The dust is visible in this natural-color image, acquired on March 15, 2021, with the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Aqua satellite. The plume appears to originate from the Taklamakan Desert in northwest China. The dry, barren area is a major source of airborne dust that can travel especially high and far on the strong winds of spring. From the Taklamakan, the dust moved eastward for thousands of kilometers. In areas where the dust stays close to the ground, such storms can diminish air quality. That was the case in Beijing, where the high concentration of particles caused air quality to reach well into the “hazardous” level of the Air Quality Index. Dust tinted the sky orange, reducing visibility to less than 1000 meters (3,300 feet).

Dust storms commonly occur across Asia in springtime. But in March 2021 meteorological spring was just getting underway, and already an enormous plume of sand and dust has blanketed northern China. It has been called the largest and strongest such storm to strike the region in a decade. The dust is visible in this natural-color image, acquired on March 15, 2021, with the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA’s Aqua satellite. The plume appears to originate from the Taklamakan Desert in northwest China. The dry, barren area is a major source of airborne dust that can travel especially high and far on the strong winds of spring. From the Taklamakan, the dust moved eastward for thousands of kilometers. In areas where the dust stays close to the ground, such storms can diminish air quality. That was the case in Beijing, where the high concentration of particles caused air quality to reach well into the “hazardous” level of the Air Quality Index. Dust tinted the sky orange, reducing visibility to less than 1000 meters (3,300 feet).

The Tarim Basin is the country's largest inland basin. It has been the home of 36 independent city states. However, as the Taklamakan Desert inexorably expanded, all the kingdoms were gradually swallowed by the shifting sand dunes, which can reach a height of 250 meters. Loulan was one of the kingdoms that lost this battle with nature. The habit of filling the unknown wilds with strange and savage creatures of terrible mien seems to be one that was common to primitive men. Numerous examples will occur to readers of classical literature and to students of anthropology. As for the demons and hobgoblins that fill the desert and waste places, classical and Biblical literature, as well as the folk-lore of all lands, record this as the common belief. Fa Hsien, a Buddhist monk, crossed the Taklamakan Desert in A.D. 399, and speaks of it as inhabited by evil demons, yet modern historians give much credit to Fa Hsien's account of his visit to India. Hsüang Chuang, another Buddhist monk, crossed the same desert of shifting sands twice in the seventh century, and tells how he “encountered all sorts of demon shapes and strange goblins."

It is not at all unlikely that the Nestorian missionaries were pursuing their course through the Taklamakan about the beginning of the seventh century. The previous century had seen their establishment in Afghanistan, and in the seventh they had reached China itself, and, as no doubt they aimed at making proselytes on the road, their progress would probably be slow. Similar remains of Nestorian and Manichaean texts have been found by Germans far away to the north-east of the Taklamakan desert, at Turfan. It is hard to think of any one spot on the earth's surface where so many divergent elements of culture and belief, or so many differing traditions, can be brought together on an historical basis. Marco Polo, in the thirteenth century, also crossed this desert, and repeats the story of wicked spirits that seek to lead the traveler astray.

The Great Wall of China was not constructed as a single project. There were two major periods of construction on the Great Wall, one during the Qin and Han dynasties, and the second during the Ming dynasty. During the first period the wall was not one extensive wall, but was rather numerous shorter fortifications. The Ming Dynasty structure can be seen from Hebei province to Gansu province. Beyond Gansu province the wall becomes a series of watchtowers that stretch into Xinjiang province and the Taklamakan desert.

Towards the end of the 19th century the “British collection of Central Asian antiquities,” which had been formed at Calcutta with the assistance of the government of India, received from the Taklamakan region very notable additions consisting of manuscripts, ancient pottery, and other remains. These objects had been sold to the political representatives of the Indian government in Kashgar, Kashmir, and Ladak, as finds made by native “treasure seekers” at ancient sites near Khotan and in the neighboring portions of the Taklamakan Desert. A curious feature of these acquisitions was that, besides undoubtedly ancient documents in Indian and Chinese characters, they contained a large proportion of manuscripts and “blockprints” in a surprising variety of entirely unknown scripts. While the materials thus accumulated, no reliable information was ever forthcoming as to the exact origin of the finds or the character of the ruined sites which were supposed to have furnished them.

The natives who set the relics drifting, and who brought their scraps of jade, and leaf-gold, and papyrus, to the spectacled Europeans in the Border towns, would tell tales of the Taklamakan Desert, and of the streets in the sand, and the dusty orchards, that cropped up like landmarks to the jackals. Old Chinese stories, written by pilgrims who had followed the track into India fifteen hundred years ago, spoke of great cities to the south of the Taklamakan, where prayer never ceased, night nor day, but ever the ritual droned among the tinkle of the little bells. Legend and tale both pointed to a fruitful harvest for the excavator. The fine hot sand blowing over the wrecked cities would preserve their treasures as drugs and spices an Egyptian. There lay the land. It skirted the trade-route from Europe into the Far East. It bordered the path of pilgrims from China to the Buddhist temples of India ; and the path of missionaries, or fakirs, from India into China. It was a veritable land of promise.

No part of Chinese Turkestan had as yet been explored from an archæological point of view, and, however much attention these discoveries attracted among competent European orientalists, it was evident that their full value for the ancient history and culture of Central Asia could never be realized without accurate researches on the spot. The practicable nature of such investigations was proved by the memorable march which Dr. Sven Hedin made in the winter of 1895–96 through the Taklamakan Desert northeast of Khotan, and of which the first accounts reached me in 1898. It had taken the famous Swedish explorer past two areas of sand-buried ruins, and, though his necessarily short halt at each had not permitted of any exact evidence being secured as to the character and date of the ruins, this discovery amply sufficed to demonstrate both the existence and comparative accessibility of ancient sites likely to reward excavation.

The lost kingdom of Loulan was brought into the light when the Swedish adventurer Sven Hedin was exploring the Lake Lop Nur area. Hedin accidentally discovered the ruins of the kingdom buried under the yellow sands of the Taklamakan Desert. This historic discovery immediately stirred a great sensation worldwide. It set off a race of archaeologists, historians and explorers from all over the world to this site. Their excavations found more remains of buildings and a wealth of fascinating remnants of this lost civilization, including coins, wood carvings, lacquer and copper ware, silk fabrics, as well as numerous documents and splendid murals. They lifted the veil of the ancient kingdom and allowed catching a glimpse of its splendid history and culture.

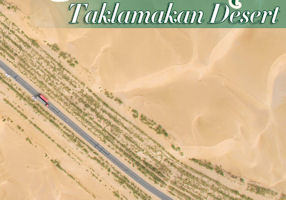

Although technically neighbors, Tajikistan’s Pamir Mountains and China’s Taklamakan Desert represent major geographical obstacles for rail and truck shipments. Tarim Desert Highway, also known as the Cross-Desert Highway (CDH) or Taklamakan Desert Highway, crosses the Taklamakan Desert from north to south, 552 km long. It take about 5hrs by car to travel the whole length. This highway links the cities of Luntai on National Highway 314 and Minfeng on National Highway 315, on the northern and southern edges of the Tarim Basin. The total length of the highway is 552 km; approximately 446 km of the highway cross uninhabited areas covered by shifting sand dunes, making it the longest such highway in the world. On both sides of a 565-km road that was built across the desert to boost Xinjiang's economy, more than 20 million trees have been planted. It remains unclear whether China's largest desert is getting bigger or smaller. However, many "green corridors through the desert" can be seen from the sky.

The desert highway runs north and south through the Taklimakan Desert, known as the "Sea of Death". The pavement structure of the desert section is in order from top to bottom: asphalt, asphalt concrete, graded gravel natural gravel, geotextile, aeolian sand foundation. The sand control system with geogrid method with Chinese characteristics is economical and reliable, that is, the reeds of Xinjiang are used to make grass squares to fix the sand. 30-50 cm, and adjust appropriately according to the position of the tuyere. Outside the grass square, there is a reed sand barrier, buried 0.3 meters in the sand, the actual height is 1.2 meters. The Shaomu Highway has prepared passages for conventional vehicles for the exploration and development of oil and gas resources in the hinterland of the Tazhong Desert.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|