People's Republic of China - People

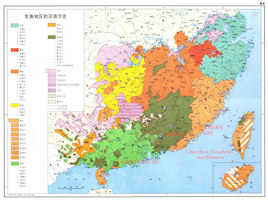

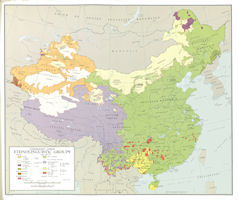

China has 56 ethnic groups, with the majority Han comprising more than 91 percent of the country’s population of 1.4 billion people. There are 12 million Uyghurs in Xinjiang, up to seven million Tibetans in the Tibet Autonomous Region, and nearly six million Mongols, mainly concentrated in the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region on China’s northern border with Mongolia and Russia.

President Xi Jinping said 09 Decembe 2024 common Chinese language, or Mandarin, should be “spoken more broadly” in border regions, adding to longstanding concerns about the impact on China’s ethnic minority languages, which some of their speakers say are struggling to survive. China’s borderlands, spanning five provinces and four autonomous regions, including Tibet, Xinjiang Uygur and Inner Mongolia, are culturally and linguistically diverse and have seen opposition to Beijing’s efforts to assimilate ethnic minorities into the majority Han culture. While Mandarin is China’s official language, efforts to promote it have sparked controversy, with critics warning of harm to ethnic languages and cultural identities.

“We should continue to deepen efforts on ethnic unity and progress, actively build an integrated social structure and community environment, and promote the unity of all ethnic groups – like pomegranate seeds tightly held together,” said Xi, addressing a Politburo study session. Xi also said Mandarin, colloquially known as Putonghua, and its writing system should be comprehensively popularized in border regions, and the use of national textbooks compiled under central guidance should be fully implemented, the state-run People’s Daily newspaper reported.

He told members of the ruling party’s top policymaking body that it was necessary to guide all ethnic groups in border regions to “continuously enhance their recognition of the Chinese nation, Chinese culture and the Communist Party”. The Chinese leader added that maintaining security and stability was the “baseline requirement” for border governance, noting that efforts should be made to improve social governance, infrastructure and “the overall ability to defend the country and safeguard the border”.

President Xi Jinping’s call for ethnic minority groups to put the interests of the nation first has fueled concerns that the government will double down on up its repressive policies against them, analysts said. Xi’s speech at the two-day Central Conference on Ethnic Affairs in Beijing in late August 2021 focused on guiding ethnic groups to put the interests of China above all else and to share a sense of community with the Chinese nation.

Xi told assembled officials they must strive to prevent risks and hidden dangers in ethnic affairs. “[We] should hold the ground of ideology. [We] should actively and steadily address the ideological issues that involve ethnic factors, and continue to eradicate poisonous thoughts of ethnic separatism and religious extremism,” Xi was quoted as saying by Xinhua news agency. “International anti-terrorism cooperation should be also intensified, working with major countries, regions, international organizations and overseas Chinese ethnic minorities,” added Xi, who is general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party’s Central Committee.

The uneven pattern of internal development, so strongly weighted toward the eastern part of the country, doubtless will change little even with developing interest in exploiting the mineral-rich and agriculturally productive portions of the vast northwest and southwest regions. The adverse terrain and climate of most of those regions have discouraged dense population. For the most part, only ethnic minority groups have settled there. Because some of the groups were located in militarily sensitive border areas and in regions with strategic minerals, the government tried to maintain benevolent relations with the minorities. But the minorities played only a superficial role in the major affairs of the nation.

Since 1949 government policy toward minorities had been based on the somewhat contradictory goals of national unity and the protection of minority equality and identity. The state constitution of 1954 declared the country to be a "unified, multinational state" and prohibited "discrimination against or oppression of any nationality and acts which undermine the unity of the nationalities." All nationalities were granted equal rights and duties. Policy toward the ethnic minorities in the 1950s was based on the assumption that they could and should be integrated into the Han polity by gradual assimilation, while permitted initially to retain their own cultural identity and to enjoy a modicum of self-rule. Accordingly, autonomous regions were established in which minority languages were recognized, special efforts were mandated to recruit a certain percentage of minority cadres, and minority culture and religion were ostensibly protected. The minority areas also benefited from substantial government investment.

Yet the attention to minority rights took place within the larger framework of strong central control. Minority nationalities, many with strong historical and recent separatist or anti-Han tendencies, were given no rights of self-determination. With the special exception of Xizang in the 1950s, Beijing administered minority regions as vigorously as Han areas, and Han cadres filled the most important leadership positions. Minority nationalities were integrated into the national political and economic institutions and structures. Party statements hammered home the idea of the unity of all the nationalities and downplayed any part of minority history that identified insufficiently with China Proper. Relations with the minorities were strained because of traditional Han attitudes of cultural superiority. Central authorities criticized this "Han chauvinism" but found its influence difficult to eradicate.

Pressure on the minority peoples to conform were stepped up in the late 1950s and subsequently during the Cultural Revolution. Ultraleftist ideology maintained that minority distinctness was an inherently reactionary barrier to socialist progress. Although in theory the commitment to minority rights remained, repressive assimilationist policies were pursued. Minority languages were looked down upon by the central authorities, and cultural and religious freedom was severely curtailed or abolished. Minority group members were forced to give up animal husbandry in order to grow crops that in some cases were unfamiliar. State subsidies were reduced, and some autonomous areas were abolished. These policies caused a great deal of resentment.

After the arrest of the Gang of Four in 1976, policies toward the ethnic minorities were moderated regarding language, religion and culture, and land-use patterns, with the admission that the assimilationist policies had caused considerable alienation. The new leadership pledged to implement a bona fide system of autonomy for the ethnic minorities and placed great emphasis on the need to recruit minority cadres.

Since 1979 the government had advocated a one child limit for both rural and urban areas and has generally set a maximum of two children in special circumstances. As of 1986 the policy for minority nationalities was two children per couple, three in special circumstances, and no limit for ethnic groups with very small populations.

Under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, the Chinese government in the mid-1980s pursued a liberal policy toward the national minorities. Full autonomy became a constitutional right, and policy stipulated that Han cadres working in the minority areas learn the local spoken and written languages. Significant concessions were made to Xizang, historically the most nationalistic of the minority areas. The number of Tibetan cadres as a percentage of all cadres in Xizang increased from 50 percent in 1979 to 62 percent in 1985. In Zhejiang Province the government formally decided to assign only cadres familiar with nationality policy and sympathetic to minorities to cities, prefectures, and counties with large numbers of minority people. In Xinjiang the leaders of the region's fourteen prefectural and city governments and seventy-seven of all eighty-six rural and urban leaders were of minority nationality.

Members of China's ethnic minorities serve in the PLA, but their percentage within the military was probably considerably lower than their proportion in the general population, partly because of their lower level of education and partly because of government and party suspicion of their loyalties.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|