China - Climate Change

Despite claims of international environmental leadership, China’s energy-related carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions are rising. It has been the world’s largest annual greenhouse gas (GHG) emitter since 2006. China’s total emissions are twice that of the United States and nearly one third of all emissions globally. Beijing’s energy-related emissions increased more than 80 percent between 2005-2019, while U.S. energy-related emissions have decreased by more than 15 percent. In 2019 alone, China’s energy-related CO2 emissions increased more than 3 percent, while the United States’ decreased by 2 percent. Beijing claims “developing-country” status to avoid shouldering more responsibility for reducing GHG emissions–though its per capita CO2 emissions have already reached the level of many high-income countries. China’s increasing emissions counteract the progress of many other countries around the world to reduce global emissions.

Through the Montreal Protocol, the nations of the world agreed to phase out production of substances that damage the ozone layer. But scientists identified an increase of emissions of the phased-out, ozone-depleting substance CFC-11 from Eastern China from 2014 to 2017. The United States leads the international response and continues to push China to live up to its obligations and increase its monitoring and enforcement efforts.

In 2008, U.S. diplomats installed air quality monitors on top of U.S. Embassy Beijing. We shared the data publicly and revealed what local residents already knew: Beijing’s air quality was dangerously worse than the Chinese government was willing to admit. That small act of transparency helped catalyze a revolution in air quality management, and Beijing has since made air quality a priority, including establishing new ambient air quality standards. Despite significant improvements in large cities, the overall level of air pollution in China remains unhealthy, and air pollution from China continues to affect downwind countries.

China is home to more than three-quarters of the regions most at risk from climate change, with some of the world’s most important manufacturing centres threatened by extreme weather. China’s eastern Jiangsu province ranks as the world’s most climate-vulnerable region, followed by Shandong, Hebei and Henan, according to the report released on 20 February 2023 by climate risk specialists XDI.

After China, the United States is home to the most at-risk areas, according to XDI. Florida, which is ranked 10th globally, is the US state most under threat, followed by California and Texas. Nine areas of India also made the top 50 at-risk regions. Other major economic centres in the top 100 include Argentina’s Buenos Aires, Vietnam’s Ho Chi Minh City, and Indonesia’s Jakarta. In Europe, Germany’s Lower Saxony region is deemed the most vulnerable to climate change. Italy’s Veneto region, which contains the city of Venice, is ranked the fourth most at-risk region in Europe.

XDI’s analysis assessed 2,600 territories globally, modelling damage from 1990 to 2050 based on the “pessimistic” scenario of a 3 degrees Celsius (5.4 degrees Fahrenheit) rise in global temperatures by the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Monsoon winds, caused by differences in the heat-absorbing capacity of the continent and the ocean, dominate the climate. Alternating seasonal air-mass movements and accompanying winds are moist in summer and dry in winter. The advance and retreat of the monsoons account in large degree for the timing of the rainy season and the amount of rainfall throughout the country. Tremendous differences in latitude, longitude, and altitude give rise to sharp variations in precipitation and temperature within China. Although most of the country lies in the temperate belt, its climatic patterns are complex.

China's northernmost point lies along the Heilong Jiang in Heilongjiang Province in the cold-temperate zone; its southernmost point, Hainan Island, has a tropical climate. Temperature differences in winter are great, but in summer the diversity is considerably less. For example, the northern portions of Heilongjiang Province experience an average January mean temperature of below 0°C, and the reading may drop to minus 30°C; the average July mean in the same area may exceed 20°C. By contrast, the central and southern parts of Guangdong Province experience an average January temperature of above 10°C, while the July mean is about 28°C.

Precipitation varies regionally even more than temperature. China south of the Qin Ling experiences abundant rainfall, most of it coming with the summer monsoons. To the north and west of the range, however, rainfall is uncertain. The farther north and west one moves, the scantier and more uncertain it becomes. The northwest has the lowest annual rainfall in the country and no precipitation at all in its desert areas.

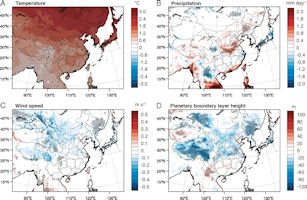

Seasonal changes in different Chinese regions (region definitions are provided in SI Appendix, Table S1) are also summarized in SI Appendix, Fig. S1. Mean surface temperature increases over all regions and in all seasons, with the greatest increases in the northeast [consistent with previous studies. Rising temperatures lead to increased evaporation and atmospheric water vapor, with projected increases in precipitation in the north and south regions. Circulation changes will complicate precipitation patterns at regional scales. Mean wind speeds are projected to decline slightly over most of the regions and in all seasons, with similarly widespread decreases in the planetary boundary layer height, especially in winter. Together, these decreases in wind speed and boundary layer height indicate a more stable atmosphere in the future.

As a developing country with a population of more than 1.3 billion, China is among those countries that are most severely affected by the adverse impacts of climate change. China is currently in the process of rapid industrialization and urbanization, confronting with multiple challenges including economic development, poverty eradication, improvement of living standards, environmental protection and combating climate change. To act on climate change in terms of mitigating greenhouse gas emissions and enhancing climate resilience, is not only driven by China’s domestic needs for sustainable development in ensuring its economic security, energy security, ecological security, food security as well as the safety of people’s life and property.

As a developing country at a low development stage, with a huge population, a coal-dominant energy mix and relatively low capacity to tackle climate change, China will surely face more severe challenges when coping with climate change along with the acceleration of urbanization, industrialization and the increase of residential energy consumption.

Because of the coal-dominated energy mix, CO2 emission intensity of China’s energy consumption is relatively high. China’s primary energy mix is dominated by coal. In 2005, the primary energy production in China was 2,061 Mtce, of which raw coal accounted for as high as 76.4%. For the same year, China’s total primary energy consumption was 2,233 Mtce, among which, the share of coal was 68.9%, oil 21.0%, and natural gas, hydropower, nuclear power, wind power and solar energy 10.1%.

In 2009, China announced internationally that by 2020 it will lower carbon dioxide emissions per unit of GDP by 40% to 45% from the 2005 level, increase the share of non-fossil fuels in primary energy consumption to about 15% and increase the forested area by 40 million hectares and the forest stock volume by 1.3 billion cubic meters compared to the 2005 levels.

China has relatively harsh climatic conditions. Most of China has a continental monsoon climate with more drastic seasonal temperature variations compared with other areas at the same latitude such as North America and West Europe. In most part of China, it is cold in winter and hot in summer with extremely high temperature. Therefore, more energy is necessary to maintain a relatively comfortable room temperature. Precipitation in China is unevenly distributed both seasonally and spatially. Most of the precipitation occurs in summer and varies greatly among regions. Annual Precipitation gradually declines from the southeastern coastal areas to the northwestern inland areas. China frequently suffers from meteorological disasters, which are unusual worldwide in terms of the scope of affected areas, the number of different disasters, the gravity of disaster and the mass of affected population.

China is a country with a vulnerable ecosystem. The national forest area for 2005 is 175 million hectares and the coverage rate is just 18.21%. China’s grassland area for the same year is 400 million hectares, most of which are high-cold prairie and desert steppe while the temperate grasslands in Northern China are on the verge of degradation and desertification because of drought and environmental deterioration. China’s total area of desertification for 2005 is 2.63 million square kilometers, accounting for 27.4% of the country’s territory. China has a continental coastline extending over 18,000 kilometers and an adjacent sea area of 4.73 million square kilometers, as well as more than 6,500 islands over 500 square meters. As such, China is vulnerable to the impacts of sea level rise.

Climate change has already had certain impacts on agriculture and livestock industry in China, primarily shown by the 2-to-4-day advancement of spring phenophase since 1980’s. Future climate change can affect agriculture and livestock industry in the following ways: increased instability in agricultural production, where the yields of three main crops, i.e. wheat, rice and maize, are likely to decline if no proper adaptation measures are taken; changes in distribution and structure of agricultural production as well as in cropping systems and varieties of the crops; changes in agricultural production conditions that may cause drastic increase in production cost and investment need; increased potential in aggravation of desertification, shrinking grassland area and reduced productivity that result from increased frequency and duration of drought occurrence due to climate warming; and potentially increased rate in disease breakout for domestic animals.

Climate change has brought impacts on forests and other natural ecosystems in China. For example, the glacier area in the northwestern China shrunk by 21% and the thickness of frozen earth in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau reduced a maximum of 4-5 meters in recent 50 years. Future climate change will continue to impact these ecosystems to some extent. Firstly, the geographical distribution of major forest types will shift northward and the vertical spectrum of mountain forest belts will move upward. The distribution range of major tree species for afforestation or reforestation and some rare tree species is likely to shrink. Secondly, forest productivity and output will increase to different extents, by 1-2% in tropical and subtropical forests, about 2% in warm temperate forests, 5-6% in temperate forests, and approximately 10% in cold temperate forests. Thirdly, the frequency and intensity of forest fires and insect and disease outbreaks are likely to increase.

Fourthly, the drying of inland lakes and wetlands will accelerate. A few glacier-dependent alpine and mountain lakes will eventually decrease in volume. The area of coastal wetlands will reduce and the structure and function of coastal ecosystems will be affected. Fifthly, the area of glaciers and frozen earth is expected to decrease more rapidly. It is estimated that glacier in western China will reduce by 27.7% by the year 2050, and the spatial distribution pattern of permafrost will alter significantly on Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Sixthly, snow cover is subjected to reduce largely with significantly larger inter-annual variation. Seventhly, biodiversity will be threatened. The giant panda, Yunnan snub-nose monkey, Tibet antelope and Taiwania flousiana Gaussen are likely to be greatly affected.

Climate change has already caused the changes of water resources distribution over China. A decreasing trend in runoff was observed during the past 40 years in the six main rivers, namely Haihe River, Huaihe River, Yellow River, Songhuajiang River, Yangtze River, and Pearl River. Meanwhile, there is evidence for an increase in frequency of hydrological extreme events, such as drought in North and flood in South. The Haihe-Luanhe River basin is the most vulnerable region to climate change, followed by Huaihe River basin and Yellow River basin. The arid continental river basins are particularly vulnerable to climate change.

In the future, climate change will have a significant impact on water resources over China: in the next 50-100 years, the mean annual runoff is likely to decrease evidently in some northern arid provinces, such as Ningxia Autonomous Region and Gansu Province, while it seems to increase remarkably in a few already water-abundant southern provinces, such as Hubei and Hunan provinces, indicating an increase of flood and drought events due to climate change; the situation of water scarcity tends to continue in the northern China, especially in Ningxia Autonomous Region and Gansu Province, where water resource per capita are likely to further decrease in future 50-100 years; providing that water resources are exploited and utilized in a sustainable manner, for most provinces, water supply and demand would be basically in balance in future 50-100 years. However, gap between water resource supply and demand might be expanded in Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, Xinjiang Autonomous Region, Gansu, and Ningxia Autonomous Region.

Floods cause more damages each year globally than any other form of natural disasters. According to the United Nations, over the 20-year period between 1995 and 2015, 157,000 people died due to floods and another 2.3 billion were affected. Currently, global average annual flood losses are estimated at $104 billion. The country incurring the highest losses is China, followed by US and India. Because of topography, high population, urbanization and tremendous economic growth during the past decades, China has had three of the 10 most costly global floods since 1950. Equally, because of population density, all the three Chinese floods resulted in high fatalities compared to the other seven floods elsewhere where deaths were in hundreds.

Yangtze is the longest river of China and the third-longest in the world. It is also the most important water artery in terms of economy and development. Thus, a serious Yangtze flood has major implications not only for China but also for the world by disrupting manufacturing and transportation links as well as the global supply chain.

China's rapidly growing cities are increasingly vulnerable to fatal flash floods in streets and underpasses as mushrooming construction projects fail to plan for storm drainage. Recent figures show that 62 percent of China's cities are vulnerable to flash floods as rapidly developed urban areas lack the drainage capacity to handle severe rainstorms. The lack of storm drainage means the water transforms highly developed cityscapes into lakes, rivers, and waterfalls overnight. Governments would prefer that projects they invest in were highly visible. If you build drains, not everyone will see it, and particularly your superiors won't be able to see it.

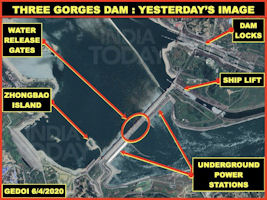

The main flood season in the Yangtze river basin is usually July and August. Huge rainstorms in China's Yangtze river basin in July 2016 left more than 120 people are dead and more than 40 missing, with more than a million forced out of their homes by widespread flooding. The official Xinhua news agency estimated that more than 38 billion yuan (U.S. $5 billion) worth of damage has been done, as the region is battered by particularly heavy summer rains. Officials warned that a strong El Nino effect this year will increase the risk of flooding in the Yangtze and Huai river basins, recalling the 1998 Yangtze flood disaster that left more than 4,000 people dead. Torrential rains in the Yangtze river basin in late June 2020 coupled with the release of floodwater from the massive Three Gorges hydroelectric dam upstream left major cities along the river submerged. Heavy rains in the Yangtze region have left at least 12 people dead and more than 10 million people affected by the floods, with social media footage showing drowned streets with cars and scooters swept away by turbulent, muddy waters. In the Yangtze river city of Yichang, residents blamed recent releases of water from the Three Gorges and Gezhouba dams upstream of the city for flooding.

The Three Gorges Dam is playing its crucial role in retaining and intercepting flood water. Stories fantasizing the dam being close to collapse pop up annually. There have been frequent rumors that the Three Gorges Dam is "deformed" or even close to collapse. In July 2019, a picture posted online showed a satellite image of a "crooked" Three Gorges Dam caught quite some eyeballs. It proved to be an unfounded rumor after the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation provided a high-resolution satellite picture of the dam that shows no deformity.But according to experts, even in face of severe floods and torrential rain this year, the dam will stay firm and strong as ever, if not stronger, rather than deformed or collapsed. Three Gorges Dam has 23 deep spillway holes and 22 surface spillway holes to efficiently release flood water and hence stay firm. China's largest recorded flood in the past 2,500 years was in 1870 with a peak flow of 105,000 cubic meters per second. The Three Gorges Dam is designed to withstand more, even a peak flow of 124,300 cubic meters per second.

As of July 2020 there was 21.1 billion m3 of flood control capacity on stand-by in the Three Gorges Reservoir, and risks in the Yangtze River basin were under control. Flooding in the South China in 2020 was caused by the combined force of the Western Pacific subtropical high, westerly belt, plateau snow and global climate anomaly.

Changing weather patterns may impact businessin a variety of ways, including the physical riskto fixed assets arising from storm damage orflood, impacts on the supply chain arising fromincreasing scarcity of natural resources suchas water, and shifting patterns in demand forgoods and services due to increased extremesof temperature. They may impact asset values,and hence potentially weaken a company’sbalance sheet; they may increase costs, as rawmaterials or other inputs become scarce, or asoperations or working practices need to change;or they may reduce or stimulate the demand fora company’s products or services.

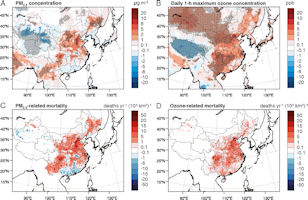

The role of climate extremes in future air quality and the associated health impacts are not well recognized and are rarely quantified. Yet, policy makers and the public are concerned not only with average air quality but also with extreme air pollution events, which may have a disproportionate effect on human health, and are thus a focus of clean air policies.

Since December 2020, the government had been challenged by an extraordinary confluence of pressures on the country's energy supplies and its ability to meet demands for home heating and economic recovery. The burdens on China's energy delivery networks and supply capacity may be the greatest in over a decade. Frigid weather across north Asia has caught utilities and liquefied natural gas (LNG) importers off guard as demand for power lowered inventories and pushed spot prices to record levels.

In Beijing, one of the coldest winters since 1966 drove temperatures down to minus 19.6 degrees Celsius (minus 3.3 degrees Fahrenheit), the official Xinhua news agency reported. The plunge in temperatures forced the capital to restart its only remaining coal-fired power plant for backup power in late December to meet peak load heating demand, Reuters said.

LNG imports at northern ports were also stalled by the spread of sea ice from 10 to 40 nautical miles or more. At the port of Tianjin, China's second-largest national oil company Sinopec spent 20 hours with an icebreaker and a hot water cannon to clear the way for docking a single LNG tanker to unload. The effort underscores how frigid temperatures have upended energy markets across Asia, catching some companies flat-footed and sending prices for electricity, fuel and vessels to record highs. At Qinhuangdao port, the backup of coal carriers waiting at anchorage reached the highest level in over two years. On 07 January 2021, temperatures at the port of Qingdao fell to the lowest level in history.

Heavy downpours and floods that struck Central China's Henan Province for days killed 25, with seven still missing as of 21 July 2021, while 160,000 were evacuated and 1.24 million people were affected. From 17 July to 20 July 20210, a total of 617.1 mm (24.3 inches) of rain fell in Zhengzhou, almost the equivalent of its annual average of 640.8 mm (25.2 inches). The three days of rain matched a level seen only "once in a thousand years", the Zhengzhou weather bureau said. Like recent heatwaves in the United States and Canada and extreme flooding seen in western Europe, the rainfall in China was almost certainly linked to global warming, scientists told Reuters. "Such extreme weather events will likely become more frequent in the future," said Johnny Chan, a professor of atmospheric science at City University of Hong Kong. "What is needed is for governments to develop strategies to adapt to such changes," he added, referring to authorities at city, province and national levels. Typhoon "Yanhua" was cited for the downpour, exerting "remote control" over Henan as water vapor was pushed from the sea to Henan following the path of the typhoon, as well as air currents. When the airflow hits the mountains in Henan, it converged and shot upwards, causing rain to be concentrated in this region.

Piles of cars were strewn across the central Chinese city of Zhengzhou on 22 July 2021 as shocked residents picked through the debris of a historic deluge that claimed at least 33 lives, with more heavy rain threatening surrounding regions. An unprecedented downpour dumped a year’s rain in just three hours on the city of Zhengzhou, weather officials said, instantly overwhelming drains and sending torrents of muddy, swirling water through streets, road tunnels and the subway system.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|