Kingdom of Araucania and Patagonia

In January 1862, the navies of Spain, Britain, and France jointly occupied the Mexican Gulf coast in an attempt to compel the repayment of public debts. Britain and Spain quickly withdrew, but the French remained and, in May 1863, occupied Mexico City. Drawing on the support of the Mexican conservatives, Napoleon III installed Austrian prince Ferdinand Maximilian von Habsburg as Mexican Emperor Maximilian I. By February 1867, a growing liberal insurgency under Juárez and the threat of war with Prussia had compelled France's withdrawal from Mexico. Maximilian was captured and executed by Juárez's forces shortly thereafter.

In January 1862, the navies of Spain, Britain, and France jointly occupied the Mexican Gulf coast in an attempt to compel the repayment of public debts. Britain and Spain quickly withdrew, but the French remained and, in May 1863, occupied Mexico City. Drawing on the support of the Mexican conservatives, Napoleon III installed Austrian prince Ferdinand Maximilian von Habsburg as Mexican Emperor Maximilian I. By February 1867, a growing liberal insurgency under Juárez and the threat of war with Prussia had compelled France's withdrawal from Mexico. Maximilian was captured and executed by Juárez's forces shortly thereafter.

This was not the first French adventure in the New World at this time. Only a few months before Maximilian ascended the throne of Mexico, Orelie-Antoine de Tounens bestowed upon himself the high-sounding title of king of Araucania and Patagonia. What can be gathered as to this obscure sovereign's career has to be taken from unsatisfactory chronicles of his own, dealing with the early part of it, and, for the rest, from scattered allusions by writers less respectful of his pretensions ; but if ever his Majesty's memory found a properly equipped historian, the result might well rival in interest some of Don Quixote's boldest exploits, not to say those of Maximilian.

He began life as a lawyer at Perigeux, in the early days of the Second Empire, which may have helped to turn his head by its example of how easily fortune favors the bold with crowns. For a time impatiently submitting to that commonplace drudgery, he seems to have been exercised in mind as to the power France had lost in America; then, fired by patriotic desire to spread the influence of his country as well as to gain for himself a more congenial sphere of action, he conceived the project of setting up a brandnew kingdom somewhere or other in the wilds of the New World. To this enterprise he committed himself single-handed, with a sanguine confidence that did not sufficiently consider the two ludicrous failures made by his imperial model before the great stroke which at length set Louis Napoleon on the throne.

The Araucanian Indians had never been subdued by their Spanish neighbors. A hardy, warlike race, the Iroquois of South America, tens of thousands strong, and so trained in riding from childhood that man and horse were like a centaur, there is little doubt that if united under a capable leader they might have given a great deal of trouble to the Chilians, who had to content themselves with a vague claim of sovereignty over the Araucanian tribes, their mutual relations being comprised in continual grudges, occasional affrays, and a border trade carried on by armed merchants through the help of interpreters. The hero of Pengeux thus showed discrimination in fixing on this region as the site of his kingdom.

The would-be sovereign of Araucania left France in 1858, but did not appear before his subjects, as yet unconscious of his existence, for a couple or so of years, during which he remained at or about Coquimbo, wisely employed in learning Spanish and picking up information as to the country he proposed to rule. By-andby he made the acquaintance of an Araucanian chief named Magnil, who, he declares, welcomed and encouraged him in his designs. This may be the chief of whom there is a story that, to secure his allegiance, M. de Tounens presented him with a grand piano, which the Indian forthwith gutted of such useless lumber as keys, strings, and so forth, to turn it into a bed for himself and his wife.

When, in 1860, the aspirant to royalty crossed the Araucanian frontier on his first visit to his castles in the air, he was met by the news of Magnil's death. Not dismayed by this misfortune, he went on so far as to open his project, by means of an interpreter, to certain other chiefs, — who — on his own authority — gave their adherence as readily as the defunct Magnil. Matters seeming thus ripe for such a step, the pretender commenced business by issuing the a decree, as regal in its tone as if he had verily been to the manner born, proclaiming "A constitutional and hereditary monarchy is founded in Araucania; Prince Orllie-Antoine de Tounens is named king." He obtained this proclamation as king of Araucania and Patagonia at a mass-meeting that was held in the valley of Los Angeles in March 1861 [other accounts report the date as the 6th of November 1860].

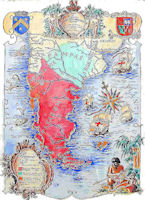

During the greater part of next year he here awaited answers to letters to friends in France, announcing what had just taken place, and asking for aid in establishing his power. The time was passed in drawing up laws for the united kingdoms of Araucania and Patagonia, which he proposed to christen New France, and to divide into departments and communes. Moreover, he supplied himself with a blue, white, and green flag, that was henceforth to be the tricolor of his States. The Chilian government as yet took no notice of these doings, probably regarding him as a harmless lunatic, while he interpreted its forbearance as an acknowledgment of Araucanian independence. For, he argues: "Is there a single king or emperor in the world who would not hasten to throw into prison an individual daring enough to come in a manner defying him, after having carved a kingdom out of his territory?"

To his disappointment, the French government withheld its recognition, and his friends at home sent no money for the Araucanian treasury. His appeal had been received with indifference or derision. Such French newspapers as did notice it, with one or two exceptions took it only as a welcome text for raillery and unworthy jests, giving Orllie-Antoine occasion to remark sorrowfully and sagaciously that his countrymen care for nothing so much as amusement, to which they will often sacrifice the gravest interests and the most momentous hopes. And yet he was offering the fatherland a realm having a coast of more than four hundred leagues on the Atlantic Ocean, and hardly less on the Pacific, with an average breadth of six hundred miles, a country twice as large as France, of rare fertility, watered by numerous streams, rich in pastures and minerals, favored by an excellent climate, and not troubled by either fierce beasts or venomous reptiles, all which he took pos session of with the intention of making it a French colony, and his ungrateful countrymen saw here nothing but a joke.

Meanwhile Orelie's letters to the French emperor began to excite the interest of Europe, and London and New York papers published editorials favorable to the cause of the adventurer. The Chilian authorities had threatened the Araucanians with war if they did not expel De Tounens, and Orelie visited the principal caciques to organize the defence. One, named Guenterol, promised to lead an army of 40,000 men in case of invasion. As Napoleon III discussed the question of Orelie's recognition in his privy council, the Chilian government saw the necessity of acting vigorously.

The Chilian authorities had information of what was going on, and woke up to the necessity of putting an end to a comedy which might end in the tragic scenes of an Indian war. The king's hireling servant, Rosales, though he had just obtained a large rise of wages, ungratefully arranged with the commandant at Nacimiento to deliver his master into the hands of the police. As Orllie Antoine, having come so far on his journey, was unsuspiciously resting under the shade of some pear-trees, he "fell into an ambuscade." In fact some half-a-dozen armed men stole up, suddenly rushed in upon him, seized his sword, packed him on a horse, and galloped off with him as fast as they could for fear of a rescue by the Indians. Seeing all lost but honor, the king yielded himself with becoming dignity. Had it not been for the interference of some traders who happened to be on the spot, he says, his captors would have cut off his head forthwith and carried it to their employers as proof of his death, according to historic precedent in such affairs.

Thus, after a reign hardly longer than Lady Jane Grey's, the king of Araucania and Patagonia found himself torn away from his territories, "against the law of nations," and consigned to the royal fate of captivity. Fearing foreign complications, all the Chilian courts affirmed their incompetency in Orelie's case. The latter meanwhile escaped from his prison, but was recaptured a few days later, and at last the Santiago court of appeals declared him a lunatic on 2 Sept., 1862, and decided to keep him a prisoner till he should be claimed by his family or the French government. However, a few days later he was put on board a ship bound for France. On 3 Dec, 1863. he addressed a protest to the foreign governments, and tried to interest the public in his case by the issue of a narrative entitled "Orelie Antoine 1., roi d'Araucanic et de Patagonie, son avenement au tronc et sa captivite au Chili" (Paris, 1863). He also began a series of lectures in the principal cities.

Toward the end of 1869 he returned to Patagonia, but was coolly received, and after a few months left for Marseilles. There he founded the journal " Les Pendus" in December. 1871, in which he narrated his second expedition. In March, 1872. he began the publication of "La Couronne d'acier," a journal of Araucania and Patagonia, and founded the order of the same name, the decoration of which he bestowed very liberally. In April. 1874, having interested some financiers in his cause, he left Bordeaux with a supply of arms and ammunition, and freighting a small schooner in Buenos Ayres, under the assumed name of Jean Prat, set out for his kingdom. But an Argentine sloop-of-war, at the request of the Chilian authorities, overtook him and brought him back on 19 July to Buenos Ayres, where ho was imprisoned. After his release, on 31 Oct., he returned to France, where he was at one time an inmate of a poor-house in Bordeaux. Having again made partisans, he formed a cabinet, and, securing the support of a wealthy retired naval officer, was preparing a new expedition, when he died in 1878.

Federico Errasuriz had scarcely taken possession of the office of President of Chile in 1871 when a conflict arose with the Argentine Confederation. Both countries disputed for a long time the sovereignty of Araucania and Patagonia, regions which until then had preserved their independence. The Argentine Senate having declared the territory of Magallanes included in the limits of the confederation, Chili hastened, in order to secure her rights, to give authority to one of her subjects to take 3000 tons of guano from the Islands of Santa Magdalena, in the Straits of Magellan. At the same time the Government took possession of all the coast of Arauco and distributed the land in those regions, in lots, to Chilian and foreign colonists; but very few cared to run the risk of taking up such concessions in consequence of the danger to life and property at such distances from the settled parts. The Indians make frequent incursions into the territory in question and carry off the women, children and cattle.

The The twentieth century biographical dictionary of notable Americans reports that Walter James Hoffhan, amuch decorated ethnologist, a member of the leading scientific and historical societies of the United States and Europe, more than forty in all, was decorated by Achilla I of Araucania and Patagonia, Nov. 7, 1887.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|