Assessments and Measures of Effectiveness in Stability Operations Handbook

Handbook 10-41

May 2010

Chapter 1 - Assessment in Stability Operations

"This is a political as well as a military war . . . the ultimate goal is to regain the loyalty and cooperation of the people. It is abundantly clear that all political, military, economic, and security (police) programs must be integrated in order to attain any kind of success." -General William C. Westmoreland, Commander, Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV), MACV Directive 525-4, 17 September 1965 |

The Necessity of Assessment

Today's adversary is a dynamic, adaptive foe who operates within a complex interconnected operational environment (OE). In recent and current operations the United States (U.S.) and coalition partners combated global terrorism in a number of regions. Stability operations are a key component of the U.S. national strategy to defeat terrorism. Within the U.S. government, the complex nature of stability operations resulted in the increased level of cooperation between the Department of Defense (DOD) and other U.S. government agencies. The goals of stability operations are stated in DOD Instruction (DODI) 3000.05, 16 September 2009:

-

4.d The Department shall assist other U.S. government agencies, foreign governments and security forces, and international governmental organizations in planning and executing reconstruction and stabilization efforts, to include:

(1) Disarming, demobilizing, and reintegrating former belligerents into civil society.

(2) Rehabilitating former belligerents and units into legitimate security forces.

(3) Strengthening governance and the rule of law.

(4) Fostering economic stability and development.

The Purpose of Assessment in Stability Operations

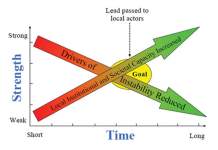

The process of assessment and measuring effectiveness of military operations, capacity building programs, and other actions is crucial in identifying and implementing the necessary adjustments to meet intermediate and long term goals in stability operations. As time passes and operations, programs, actions, and activities become effective, local institutional and societal capacity will increase and the drivers of conflict and instability will be reduced, meeting the goal of passing the lead to local authorities (see Figure 1-1).

The fusion of traditional military operations and capacity building programs of U.S. government agencies like the U.S. State Department and U.S. Agency for International Development are required to meet the challenges of restoring and enhancing stability in troubled areas and regions. Accurate and timely assessment of military operations and the actions of U.S. government departments and agencies are vital to the success of stability operations.

DoDI 3000.05, 16 September 2009, states the following:

4.a Stability operations are a core U.S. military mission that the DOD shall be prepared to conduct with proficiency equivalent to combat operations. The DOD shall be prepared to:

(1) Conduct stability operations activities throughout all phases of conflict and across the range of military operations, including combat and noncombat environments. The magnitude of stability operations missions may range from small-scale, short-duration to large-scale, long-duration.

(2) Support stability operations activities led by other U.S. government departments or agencies (hereafter referred to collectively as "U.S. government agencies"), foreign governments and security forces, international governmental organizations, or when otherwise directed.

(3) Lead stability operations activities to establish civil security and civil control, restore essential services, repair and protect critical infrastructure, and deliver humanitarian assistance until such time as it is feasible to transition lead responsibility to other U.S. government agencies, foreign governments and security forces, or international governmental organizations. In such circumstances, DOD will operate within U.S. government and, as appropriate, international structures for managing civil-military operations, and will seek to enable the deployment and utilization of the appropriate civilian capabilities.

Since most stabilization operations occur in less developed countries, there will always be a long list of needs and wants like schools, roads, health care, etc. in an area of operations (AO).

Given the chronic shortage of U.S. government personnel and resources, effective stability operations require an ability to identify and prioritize local sources of instability and stability.

The focus is on the perceptions of the local populace, what those perceptions are, and how to positively influence those perceptions. Stability operations require prioritization based on progress in diminishing the sources of instability or building on sources of stability.

For example, if U.S. government personnel believe access to information about Western culture will undercut insurgent recruiting and provide a village with an Internet café, but the village elders tell the U.S. personnel they want more water-the village is not being efficiently or effectively stabilized. By ignoring the village elders, U.S. government personnel undermine the legitimacy of the village elders within their own population, and undermine the elders' ability to maintain some semblance of order, thereby contributing to the instability. Access to information about the rest of the world via the Internet café may create a rising tide of expectations that cannot be met by the village elders or the host nation government. There may be disputes over access to the Internet café or excessive use of it by some villagers at the expense of others. Again, the U.S. government's desire to make things better and to share technology with others can lead to more, not less instability. Understanding the causal relationship between needs, wants, and stability is crucial, and in some cases are directly related, and in others they are not.

The Role of Assessment in the Operations Process

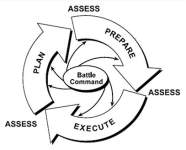

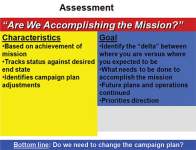

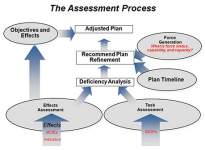

Assessment supports the operations process by charting progress and changes in an evolving situation (see Figure 1-2).

Assessment allows for the determination of the impact of events as they relate to overall mission accomplishment. Assessment provides data points and trends for judgments about progress in designated mission areas. In turn, it helps the commander determine where adjustments must be made to future operations.

Assessment assists the commander and his staff keep pace with an evolving situation. Assessment in the commander's decision cycle assists in understanding a changing environment and in focusing the staff to support critical decisions and actions.

Types of Assessment

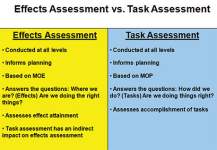

Traditionally in military operations, combat assessment focuses on the results of military action. Combat assessment uses image intelligence and signals intelligence to determine the enemy's rate of attrition. In stability operations, this is explained through the complexities of operations and political, military, economic, social, information, infrastructure, physical environment, time (PMESII-PT) systems. The two basic types of assessment in stability operations are task assessment and effects assessment.

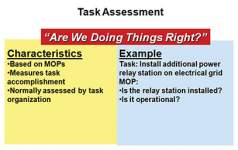

Task assessment:

Measures of performance (MOPs) are based on task assessment. Simply put, a task assessment is how well were tasks accomplished. Task assessment measures whether the organization performed its required tasks to the necessary standard. Agencies, organizations, and military units will usually perform a task assessment to ensure work is performed to standard and/or contractual obligations. Task assessment has an effect on effects assessment as tasks not performed to standard will have a negative impact on effects (see Figure 1-3).

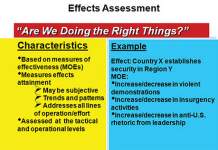

Effects assessment:

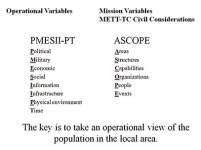

Measures of effectiveness (MOEs) are based on effects assessment. Effects assessment is defined as the process of determining whether an action, program, or campaign is productive and persuasive and achieve desired results in stability operations. There are several visualization tools that can be used as a basis of assessment. These tools: PMESII-PT; and mission, enemy, terrain and weather, troops and support available-time available, and civil considerations (METT-TC) are illustrated in Figure 1-4.

In the Army planning process, one of the six mission variables in METT-TC is civil considerations. Civil considerations tactical planning concentrates on an in-depth analysis of areas, structures, capabilities, organizations, people, and events (ASCOPE). However, at both the tactical and operational levels, PMESII-PT provides a basis for looking at the OE.

Effects assessment assesses those desired effects required to affect the adversary's behavior and capability to conduct and/or continue operations and/or actions. Effects assessment is a much broader, more in-depth, and overarching analysis of the adversary, situation, and friendly actions than traditionally seen in combat assessment (see Figure 1-5).

Rarely are military operations conducted in uninhabited areas. ASCOPE is a memory aid to organize civil considerations in Army planning. ASCOPE helps to categorize the man-made infrastructure, civilian institutions, attitudes, and activities of the civilian population and their leaders.

The results of effects assessment must be organized and measured so progress can be tracked and trends and patterns determined over time (see Figure 1-6).

It is important not to confuse task assessment (MOP) and effects assessment (MOE). The MOP is what the unit or agency does. The MOE is a measure of the effect the action has. Too often, effect and output are used interchangeably. However, they measure very different things. MOE indicators measure the effectiveness of activities against a predetermined objective. MOE indicators are crucial for determining the success or failure of stability programming. Well-devised MOEs and MOPs help commanders and their staffs understand the links between tasks, end state, and lines of effort. MOEs and MOPs have four common characteristics listed below:

- Standards should be measurable. MOEs and MOPs require qualitative or quantitative standards or metrics that can be used to measure them.

- Measurements should be distinct and discrete. MOEs and MOPs must measure a distinct aspect of the operation. Excessive numbers of MOEs or MOPs become unmanageable and risk the cost of collection efforts outweigh the value and benefit of assessment. The key is visualizing the goal and identifying the simplest and most accurate indicator of it.

- Measurements should be relevant. MOEs and MOPs must be relevant to tactical, operational, and strategic objectives or the desired end state.

- Measurements should be responsive. MOEs and MOPs must identify changes quickly and accurately enough to allow commanders to respond quickly and effectively.

The three elements of effects assessment are listed below:

- Effective effects assessment should ask "What happened?" This is the analysis of the collected data, and observations of MOEs. The data is collected and organized into presentable forms and formats. Trends and patterns are identified.

- Effective effects assessment should ask "So what? Did it make a difference in the OE." This phase determines whether the stated goals are being met.

- Effective effects assessment should ask "What do we need to do?" Options include:

- Continue current operations, actions, and programs if they are successful.

- Reprioritize operations, actions, programs, or resources. Make adjustments to current operations or programs to increase goal attainment or enhance success.

- Redirect operations, actions, programs or resources. Are major changes needed to meet goals (see Figure 1-7)?

For example, if the lack of support for the police is identified as the biggest source of instability in your AO, the stabilization objective would be to increase support for the police. MOE indicators could include improved public perception of the police, the population providing more actionable information to the police, and increased police interaction with the population. With MOEs, outcome-not output-is the only measure of success. Figure 1-8 contrasts the difference between the task and effects assessments.

The entire process from the input of MOEs and MOPs is illustrated in Figure 1-9.

The deficiency analysis is conducted when goals and objectives are not being met. The deficiency analysis is used if the task assessment and effects assessment indicate failure of units doings things right (MOP), or are not doing the right things (MOE). The deficiency analysis will illustrate what is wrong and provide input during the plan refinement stage.

The next step is a recommendation for refinement of the plan based on the conclusions of the deficiency analysis. This recommendation will also consider if the current forces available have the required capability the adjusted plan will call for. If not, other courses of action or a request for additional forces may be necessary.

Note: Objectives and effects are illustrated in the sample stabilization matrix in Appendix B.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|