Catastrophic Disaster Response Staff Officer's Handbook

Handbook 06-08

May 2006

Search and Rescue (SAR)

Appendix L

AC2 During an Incident of National Significance

Incidents of national significance are those high-impact events that require a coordinated response by federal, state, local, tribal, private-sector, and nongovernmental entities in order to save lives, minimize damage, and provide the basis for long-term community recovery and mitigation activities. An effective way to frame a discussion about AC2 during an incident of national significance is to relate AC2 to the Gulf Coast natural disasters of 2005.

Background: Hurricanes Katrina and Rita, August/September 2005

On August 29, 2005, the category five Hurricane Katrina made landfall and in less than 48 hours the scope of that natural disaster overwhelmed Gulf Coast state and local response capabilities. When the category four Hurricane Rita made landfall on September 24, 2005, the regional situation deteriorated further. The Department of Defense (DOD) participated in an unprecedented disaster response effort in support of the lead federal agency (LFA), the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA).

U.S. Northern Command (USNORTHCOM) exercised its homeland defense responsibilities and established two disaster response joint task forces (JTFs): Katrina (JTF-K) commanded by 1st Army , Fort Gillem, Georgia, and Rita (JTF-R) commanded by 5th Army, Fort Sam Houston, Texas.

In addition, 1st Air Force, Tyndall Air Force Base (AFB), Florida was designated to perform command and control for Air Force assets supporting air operations in and around the Katrina joint operating area. To exercise this responsibility, 1st Air Force established the 1st Air Expeditionary Task Force (1 AETF), Tyndall AFB, Florida, to be the Air Force service component of JTF-Katrina. When 5th Army stood up JTF-Rita, 1st AETF became JTF-Rita’s Air Force service component.

1st AETF was responsible for coordinating and integrating relief operations with local, state, and federal agencies. It established air expeditionary groups (AEGs) at Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport, Louisiana; Alexandria, Louisiana; Keesler AFB, Mississippi; Jackson, Mississippi; and Maxwell AFB, Alabama. These AEGs supported forward-deployed Airmen on the periphery of the disaster area.

1AF: Provided centralized command for all JTF Katrina and JTF Rita military air assets. As the senior military aviation command and control (C2) agency in the U.S., 1AF is responsible for centralized planning while the airborne C2 platform (Airborne Warning and Control System [AWACS]) is responsible for decentralized execution (http://www.e-publishing.af.mil/pubfiles/af/dd/afdd2-1.7/afdd2-1.7.pdf).Through partnership with the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and other government agencies, 1AF maintains an open line of communication to ensure standing operating procedures are established and followed.

JFACC: The 1AF Commander is JFACC for JTF Katrina and JTF Rita. In this role he acts as the airspace control authority (ACA) and the air defense commander (ADC). The ACA establishes airspace in response to joint force commander (JFC) guidance. During the Gulf Coast disaster the ACA integrated military aviation operations into the National Airspace System (NAS) and coordinated JTF Katrina and JTF Rita airspace requirements. The ACA develops the airspace control plan (ACP) and, after JFC approval, promulgates it throughout the area of operations (AO) and with civilian agencies. The ACA delegates airspace coordination responsibilities to the air and space operations center (AOC).

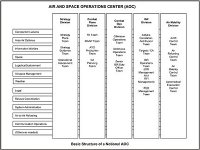

AOC: The AOC is organized under a director, with five divisions (strategy; combat plans; combat operations; intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance; and air mobility) and multiple support/specialty teams. Each integrates numerous disciplines in a cross-functional team approach to planning and execution. Each AOC is uniquely tailored to the local environment, resource availability, operational demands, and command relationships of the military and civilian hierarchy. In support of the FAA’s statutory air traffic management responsibilities, military air operations are designed to exert minimal negative impact on the NAS. (Figure A11-1 depicts the basic structure of a notional AOC).

FAA: The FAA exercises positive control of all air traffic operating within designated control areas by managing separation of aircraft.

NAS: The NAS is an interconnected system of airports, air traffic facilities and equipment, navigational aids, and airways.

ACP: The ACP provides specific planning guidance and procedures for the airspace control system for the joint operations area (JOA), including airspace control procedures. The ACP is distributed as a separate document or as an annex to the operations plan. The airspace control order (ACO) implementation directive of the ACP is normally disseminated as a separate document. The ACO provides the details of the airspace control measures (ACM).

Implementation

The ACP outlines airspace procedures for assessment, search, rescue, recovery, and reconstitution operations in the FEMA-declared disaster areas along the Gulf Coast from Baton Rouge, Louisiana, east to Mobile, Alabama.

In general terms, the ACP can be used for other military operations within the scope directed by the JFACC. In the case of the Gulf Coast disaster, it was designed to combine the FAA regional air traffic management capability with the military rescue resources and create a cohesive unit.

The ACP is based on the premise that civilian air traffic control (ATC) facilities and communications would be used as long as possible to provide visual flight rules (VFR) separation. The plan contained general guidance and procedures for airspace control within the Katrina and Rita JOAs.

The ACP is a directive to all military recovery operations aircrews; air, ground, or surface (land and naval) forces; air defense sector; any current and future C2 agencies; and ground, naval, and DOD forces. Strict adherence to the ACP, as well as FAA air traffic procedures will ensure the safe, efficient, and expeditious use of airspace with minimum restrictions placed on civil or military aircraft. Total airspace deconfliction among military versus military and military versus civilian traffic would impose undue constraints on the NAS. The ATO governs JOA airspace usage by means of a pre-planned system of ACMs that can be adjusted according to mission requirements. To assist with coordination, all component services and applicable civil authorities provide liaisons to the JFACC, and all air activities are thoroughly coordinated with FAA representatives. (Figure A11-2 depicts the pre-planned system of ACMs.)

The detailed 2005 Gulf Coast natural disaster ACP can be accessed at: http://www.faa.gov/news/disaster_response/katrina/media/katrinaacp4sept.pdf

Combat Plans and Strategy Divisions: Combat Plans and Strategy Divisions are two of five elements in an AOC. These divisions apply the JFACC’s vision to the JFC’s campaign plan to build the air campaign plan and the daily air tasking order (ATO). ATOs are the orders that assign air missions to JFACC-controlled aircrews. (Source: http://www.fas.org/man/dod-101/usaf/docs/aoc12af/part03.htm)

Hurricane Katrina and Rita: The AOC became a central point of contact for those needing rescue, supplies, and flight information. The Combat Plans Division also acted as a clearinghouse for information on behalf of the FAA, from fielding hundreds of calls to the 1-800-WEATHER-BRIEF number, to ATO development, to directions regarding flights into the JOAs. These calls were then forwarded to appropriate agencies for action.

General: 1 AF airspace managers were the military and civilian air traffic controllers responsible for coordinating and integrating all JTF Katrina and JTF Rita mission airspace requirements with the FAA. They applied the positive control elements of the NAS and procedural control capabilities of Theater Battle Management Core System (TBMCS) computers.

One of the most significant challenges to publishing a complete ATO was a result of the immediate and “real time” nature of the situation. Information flowed to Combat Plans and Strategy Divisions as well as to the crisis action team (CAT), and JTF teams. Because assets were coming from all branches of the DOD, other government agencies, and foreign governments, each team had a piece of the puzzle. The picture was not complete until Combat Plans Division instituted a dedicated air asset tracker program, staffed by a planner who gathered, organized, and consolidated all aviation assets information into a single source document and posted it to the Website.

This table identifies some of the aviation assets involved in the 2005 Gulf Coast disaster response effort:

JFACC Controlled |

Non-JFACC Controlled |

Air Force |

U.S .Coast Guard |

Army |

Marine Corps |

Navy |

AMO (formerly Customs) |

ANG (Title 10) |

Local Law Enforcement |

AF Auxiliary |

Civilian Contractors |

ANG (SAD and Title 32) |

|

Canadian Forces (Sea Kings, BO-105) |

|

Republic of Mexico (MI 17s) |

|

Republic of Singapore (CH 47s) |

|

Russian Forces (AN24) |

|

Netherlands Forces |

If a non-JFACC controlled asset is transferred to the JFACC, it can then be line-tasked in the ATO. For those assets not directly controlled by the JFACC, applicable mission information appears in the special instructions (SPINS) section of the ATO for visibility and coordination purposes.

The Combat Plans Division also created two Websites to display Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Rita aviation mission data and JFACC update briefings. These Websites quickly became the fastest means of disseminating JFACC information.

“The Wild Blue Yonder”

Air Force commanders and personnel will normally lead the effort to control airspace for joint force commanders. Airmen must understand how to organize forces and how to present them to the joint force commander to ensure safety and survivability for all users of the airspace, while ensuring mission accomplishment. Military staff officers unfamiliar with AC2 also need a basic understanding of these tenets. The “Quick Users” guide below will help you get oriented once on the ground and provide a quick reference for understanding AC2 in your JOA.

The Staff Officer’s “Quick Users” Guide

1. Find out who the JFACC or J (Joint) FACC is and where he is located. 2. Find out who the centralized command is for all military air-assets. 3. Find out where FAA representatives are located. 4. Find out where the AOC is located. Visit it as soon as you can. 5. Get a copy of the ACP and get Website address/es for updated information. 6. The guidance provided in the ACP is a directive to all military recovery operations aircrews. 7. Find out what assets are JFACC/JFACC controlled (i.e., Air Force, Army, Navy) And non-controlled (i.e., Coast Guard, Marine Corps, foreign support assets). 8. Get telephone numbers and email addresses Introduction Effective SAR operations are essential in ensuring that the loss of life is mediated. During urban disasters, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) assumes the lead role in SAR operations. The U.S. Air Force assumes the lead for inland operations, while the U.S. Coast Guard conducts operations for maritime search and rescue. About Urban Search-and-Rescue (US&R) US&R involves the location, rescue (extrication), and initial medical stabilization of victims trapped in confined spaces. Structural collapse is most often the cause of victims being trapped, but victims may also be trapped in transportation accidents, mines, and collapsed trenches. US&R is considered a “multi-hazard” discipline, as it may be needed for a variety of emergencies or disasters, including earthquakes, hurricanes, typhoons, storms and tornadoes, floods, dam failures, technological accidents, terrorist activities, and hazardous materials (HAZMAT) releases. The events may be slow in developing, as in the case of hurricanes, or sudden, as in the case of earthquakes. The National Urban Search and Rescue Response System, established under the authority of the FEMA in 1989, is a framework for structuring local emergency services personnel into integrated disaster response task forces. What You Didn’t Know About US&R

US&R Participants There are many participants in the National Urban Search and Rescue Response System. These participants can be grouped into three main categories.

National Search and Rescue Committee (NSARC) The NSARC is a federal-level committee formed to coordinate civil SAR matters of interagency interest within the United States. NSARC member agencies:

US&R Task Forces FEMA can activate and deploy the TF to provide assistance in structural collapse rescue or pre-position them when a major disaster threatens a community. Each TF must have all its personnel and equipment at the embarkation point within six hours of activation. The TF can be dispatched and en route to its destination in a matter of hours. Each TF is comprised of almost 70 specialists and is divided into six major functional elements: search, rescue, medical, HAZMAT, logistics, and planning. The TF is divided into two 35-member teams, which allows for the rotation and relief of personnel for round-the-clock SAR operations. TFs also have the flexibility to reconfigure and deploy as one 28-person (Type-III) team to respond to small, primarily weather-driven incidents, where the requirements would be physical, technical, and canine SAR in light, wood-frame construction. Such events typically include hurricanes, tornados, ice storms, and typhoons. Some of the capabilities of the US&R TFs are:

TFs by Location

Profile of a Rescue While every SAR assignment is unique, a rescue might go something like this:

Search Assessment Marking

FEMA TF Tools and Equipment

United States Coast Guard (USCG) In 1956, with the publishing of the first National Search and Rescue Plan, the USCG was designated the single federal agency responsible for maritime SAR and, likewise, the United States Air Force (USAF) was designated the single federal agency responsible for federal-level SAR for the inland regions. In order to meet the need for trained USCG and USAF SAR planners, the Joint Service National Search and Rescue School was established at Governors Island, New York ,on 19 April 1966. This action created a facility devoted exclusively to training professionals to conduct SAR. With $15,000 and a vacant WWII barracks building, six highly experienced USCG and USAF personnel formed the National SAR School. Since the first class over thirty years ago, over 14,000 have joined the ranks of trained SAR professionals. This includes over 1,400 international students from 103 nations. The school was moved to the USCG Reserve Training Center (RTC) Yorktown (now USCG TRACEN Yorktown), Virginia, in 1988. The curriculum of the school has been changed over the years to include newly developed computer search planning programs and advances in search theory and application. Additionally, many instructional technology changes have been incorporated, which allow the school to maintain its distinction as the premier school of its type in the world. SAR is one of the USCG's oldest missions. Minimizing the loss of life, injury, property damage, or loss by rendering aid to persons in distress and property in the maritime environment has always been a USCG priority. USCG SAR response involves multi-mission stations, cutters, aircraft, and boats linked by communications networks. The National SAR Plan divides the U.S. area of SAR responsibility into internationally recognized inland and maritime SAR regions. The USCG is the maritime SAR coordinator. To meet this responsibility, the USCG maintains SAR facilities on the East, West, and Gulf coasts and in Alaska, Hawaii, Guam, and Puerto Rico, as well as on the Great Lakes and inland U.S. waterways. The USCG is recognized worldwide as a leader in the field of SAR. Maritime Search and Rescue Background: Program Objectives and Goals SAR background statistics/information:

It is advantageous to reduce the time spent searching in order to:

The school provides search planners with the skills and practice they need to become SAR detectives and information distillers. They must aggressively pursue leads and obtain all information available to successfully prosecute cases. SAR program objectives are:

SAR program goals are (after USCG notification): Save at least 93% of those people at risk of death on the waters over which the USCG has SAR responsibility. Prevent the loss of at least 85% of the property at risk on the waters over which the USCG has SAR responsibility. USAF Air Force rescue coordination center (AFRCC) As the United States’ inland SAR coordinator, the AFRCC serves as the single agency responsible for coordinating on-land federal SAR activities in the 48 contiguous United States, Mexico, and Canada. The AFRCC operates 24 hours a day, seven days a week. The center, located at Langley Air Force Base, Virginia, directly ties in to the FAA’s alerting system and the U.S. Mission Control Center. In addition to the SAR satellite-aided tracking information, the AFRCC computer system contains resource files that list federal and state organizations that can conduct or assist in SAR efforts throughout North America. When a distress call is received, the center investigates the request; coordinates with federal, state, and local officials; and determines the type and scope of response necessary. Once verified as an actual distress situation, AFRCC requests support from the appropriate federal SAR force. This may include Civil Air Patrol (CAP), USCG or other DOD assets, as needed. State agencies can be contacted for state, local, or civil SAR resource assistance within their jurisdiction. The AFRCC chooses the rescue force based on availability and capability of forces, geographic location, terrain, weather conditions, and urgency of the situation. During ongoing SAR missions, the center serves as the communications hub and provides coordination and assistance to on-scene commanders or mission coordinators in order to recover the mission’s objective in the safest and most effective manner possible. AFRCC uses state-of-the-art technology including a network of satellites for monitoring emergency locator transmitter signals. Systems such as these help reduce the critical time required to locate and recover people in distress. The AFRCC also formulates and manages SAR plans, agreements, and policies throughout the continental United States. Additionally, it presents a mobile Search Management Course to CAP wings throughout the U.S. to produce qualified incident commanders, thus improving national SAR capability. The AFRCC also assigns instructors to the National SAR School at the USCG Reserve Training Center. The instructors teach the Inland Search and Rescue Class throughout the United States and at many worldwide military locations. This joint school is designed for civilian and military personnel from federal, state, local, and volunteer organizations, all of who are responsible for SAR mission planning. SAR missions include a variety of missions: searches for lost hunters, hikers, or Alzheimer’s patients; sources of emergency locator transmitter signals; and missing aircraft. The center frequently dispatches rescue assets to provide aid and transportation to people needing medical attention in remote or isolated areas, for emergency organ or blood transportation, or for medical evacuations, when civilian resources are not available. Before 1974, the USAF divided the continental United States into three regions, each with a separate rescue center. In May of that year, the USAF consolidated the three centers into one facility at Scott AFB, Illinois. This consolidation provided better coordination of activities, improved communications, and economy of operations and standardized procedures. In 1993, AFRCC relocated to Langley AFB, Virginia, when Air Combat Command assumed responsibility for USAF peacetime and combat SAR. In October 2003, the center was realigned under the USAF Special Operations Command. Since the center opened in May 1974, more than 13,500 lives have been saved from its missions. Disaster Response versus Civil SAR Aspects of disaster response (DR) and civil SAR tend to be confused, because they overlap in certain aspects, such as responsible agencies and resources used and both involve emergency response. The following information is intended to point out some of the basic differences between DR and SAR in a way that may be helpful to any persons or organizations involved in both; however, it does not address how states or localities deal with these missions and their differences.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|