Thin Man

While experiments on the gun and implosion methods continued, William S. "Deke" Parsons directed much of his effort toward developing bomb hardware, including arming and wiring mechanisms and fusing devices. Working with the Army Air Force, Parsons's group developed two bomb models by March 1944 and began testing them with B-29s. "Thin Man," supposedly named for President Roosevelt, utilized the plutonium gun design, while "Fat Man", said to be named after Winston Churchill, was an implosion prototype. (Emilio Segre's lighter, smaller uranium design became "Little Boy," Thin Man's brother).

While experiments on the gun and implosion methods continued, William S. "Deke" Parsons directed much of his effort toward developing bomb hardware, including arming and wiring mechanisms and fusing devices. Working with the Army Air Force, Parsons's group developed two bomb models by March 1944 and began testing them with B-29s. "Thin Man," supposedly named for President Roosevelt, utilized the plutonium gun design, while "Fat Man", said to be named after Winston Churchill, was an implosion prototype. (Emilio Segre's lighter, smaller uranium design became "Little Boy," Thin Man's brother).

Parsons, in charge of ordnance engineering, directed his staff to design two artillery pieces of relatively standard specifications except for their extremely light barrels -- one for a uranium bomb and one for a plutonium bomb. The guns needed to achieve high velocities, but they would not have to be durable since they would only be fired once. Here again early efforts centered on the more problematic plutonium weapon, which required a higher velocity due to its higher risk of predetonation. Two plutonium guns arrived in March 1944 and were field-tested successfully.

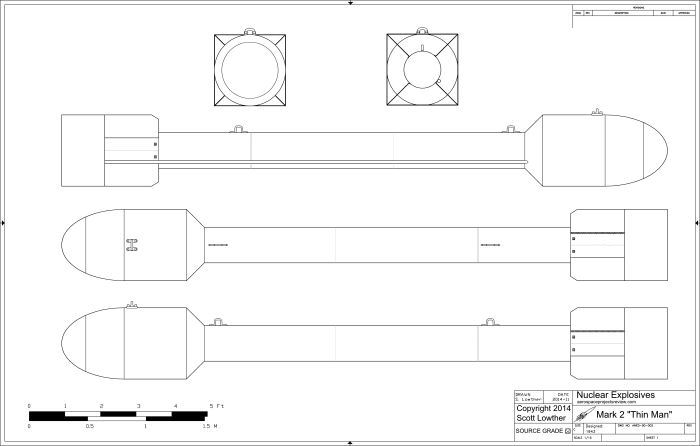

Fixing the physical size of the bomb proved important when it came to selecting a suitable aircraft to carry it. Thin Man was 17 feet (5.2 m) long, with 38-inch (97 cm) wide tail and nose assemblies, and a 23-inch (58 cm) midsection. The weight was around 8,000 pounds (3,600 kg) for the final weapon model. There was only one aircraft in the Allied inventory that could carry a Thin Man unmodified: the British Avro Lancaster. However, the American Boeing B-29 Superfortress could be modified to carry it by removing part of the main wing spar and some oxygen tanks located between its two bomb bays. Subscale models of the bomb were dropped from a Grumman TBF Avenger at the US Navy test range at Dahlgren, Virginia starting in August, 1943.

In the summer of 1944, however, it became clear that, because of the plutonium-240 problem, a gun-type design would not work for the plutonium bomb. The implosion method was now transformed from an intriguing possibility into a difficult necessity. Glenn Seaborg had warned that when plutonium-239 was irradiated for a length of time it was likely to pick up an additional neutron, transforming it into plutonium-240 and increasing the danger of predetonation, i.e., the bullet and target in the plutonium weapon would melt before coming together.

Measurements taken at Oak Ridge confirmed the presence of plutonium-240 in the plutonium produced in their experimental pile (X-10). On 17 July 1944, the difficult decision was made to cease work on the plutonium gun method -- there would be no "Thin Man." Plutonium could be used only in an implosion device, but in the summer of 1944 an implosion weapon looked like a long shot.

Abandonment of the plutonium gun project eliminated a shortcut to the bomb. This necessitated revision of the estimates of weapon delivery Vannevar Bush had given the President in 1943. The new timetable, presented to General George Marshall by Leslie Groves on August 7, 1944 -- two months after "D-Day," the Allied invasion of France -- promised small implosion weapons of uranium or plutonium in the second quarter of 1945 if experiments proved satisfactory. More certain was the delivery of a uranium gun-type bomb by August 1, 1945, and the delivery of one or two more by the end of that year. Marshall and Groves agreed that Germany might well surrender by the summer of 1945, thus making it probable that Japan would be the target of any atomic bombs ready by that time.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|