Opération Extérieures (OPEX) - Barkhane

The insurgency which initially was born in Northern Mali quickly split into its neighbouring countries across the Sahel due to their weak state structure and poorly-equipped and low-skilled armed forces. Despite some success, including the 2020 killing of Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) leader Abdelmalek Droukdel, France largely failed to contain the insurgency and violence continues to terrorise the locals en masse. Almost 7,000 people died in the fight in 2020, according to data by the Armed Conflict and Location Event Data Project. And two million people have been displaced in the same time period. Coupled with the failed anti-insurgency efforts, civilian killings have prompted growing anti-French sentiment in the region where many question the presence of their former colonial power.

The insurgency which initially was born in Northern Mali quickly split into its neighbouring countries across the Sahel due to their weak state structure and poorly-equipped and low-skilled armed forces. Despite some success, including the 2020 killing of Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) leader Abdelmalek Droukdel, France largely failed to contain the insurgency and violence continues to terrorise the locals en masse. Almost 7,000 people died in the fight in 2020, according to data by the Armed Conflict and Location Event Data Project. And two million people have been displaced in the same time period. Coupled with the failed anti-insurgency efforts, civilian killings have prompted growing anti-French sentiment in the region where many question the presence of their former colonial power.

France's anti-jihadist military force in the Sahel region, which involved over 5,000 troops, will end in the first quarter of 2022, President Emmanuel Macron announced 14 July 2021. Macron had announced a gradual drawdown of France's military presence in the Sahel and the end of the existing Barkhane operation. Now he put a timeline on the end of the operation, while assuring that France was "not withdrawing" entirely from the region.

"We will put an end to Operation Barkhane in the first quarter of 2022 in an orderly fashion," Macron told troops on the eve of France's traditional Bastille Day celebrations. Macron said that he saw France's future presence as being part of a so-called Takuba international task force in the Sahel of which hundreds of French soldiers would form the "backbone". It would mean the closure of French bases and the use of special forces focused on anti-terror operations and military training. The Barkhane operation dates back to an initial deployment undertaken from January 2013 as Paris intervened to stop the advance of jihadists in Mali.

France announced 02 July 2021 that it would resume joint military operations in Mali, after suspending them in early June following the West African country's second coup in less than a year. Following consultations with the Malian transitional authorities and the countries of the region France has "decided to resume joint military operations as well as national advisory missions, which had been suspended since June 3", the armed forces minister said in a statement.

France will focus over the next six months on dismantling the Barkhane operation and reorganising the troops, Macron said 09 July 2021. Macron announced that France would reduce its force to 2,500 to 3,000 troops over the long term. The French military will shut down Barkhane bases in Timbuktu, Tessalit and Kidal in northern Mali over the next six months, and start to reconfigure its presence in the coming weeks to focus particularly on the restive border area where Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger meet. Niger’s President Mohamed Bazoum, speaking at Macron’s side, welcomed the French military support and training, but on African terms. “The main thing is that France maintains the principle of its support, its cooperation and support for the armed forces of our different countries. We need France to give us what we don’t have. We don’t need France to give us what we already have,” he said, without elaborating.

French President Emmanuel Macron on 10 June 2021 said he was ending France's eight-year operation in the Sahel region of Africa, particularly in Mali, where the country's military has been waging a battle against Islamist insurgents. Macron said the Sahel region has become "the epicenter of international terrorism" in recent years, but said that France could not maintain a "constant" presence there. "We cannot secure certain areas because some states simply refuse to assume their duties. Otherwise, it is an endless task," he said.

Macron added that the "long-term presence" of French troops " cannot be substitute" for nation states handling their own affairs, suggesting that Paris could not keep working with governments in the region which choose to negotiate with Islamist militants, or which fail to retake control of areas liberated from terrorism. "We are there in support of the countries, not as their substitute," the president added.

Macron said the mission would be shelved as part of a "profound transformation" of France's military presence in the region which would include a partial withdrawal of troops, and added that the operation would be replaced with an international force in which France would be participating. Any role for the French army would be focused on training and equipping African security forces, Macron said, adding that the timeline was still to be finalized. He gave no further details about possible troop reduction numbers.

"We will have to hold a dialogue with our African and European partners. We will keep a counter-terrorism pillar with special forces with several hundred troops...and there will be a second pillar that will engage in cooperation, and which we will reinforce," Macron promised in Thursday's remarks. He also emphasized that the remaining French presence would not be based on a "constant framework."

Macron's comments followed the recent deterioration of ties between Paris and the new authorities in Mali, which experienced a military in May 2021. France announced the suspension of joint military operations with Malian forces on 3 June, ostensibly as a precaution over the security situation in the country.

While Macron said France’s existing Operation Barkhane would end, its military presence would remain as a part of the so-called Takuba Task Force. The drawdown would mean the closure of French bases and the use of special forces who conduct anti-terror operations and provide military training to local armed forces. The Takuba operation, which according to Macron was to take the lead, currently consists of around 600 European special forces based in Mali, half of whom are French, with 140 Swedes and several dozen forces from Estonia and the Czech Republic.

France in recent years tried to internationalise and externalise counter-terrorism operations in the Sahel as the financial and political burden has become costly for Paris, which failed to secure significant contributions from its allies. Western countries had long considered involvement in the Sahel as a risky move given the ever-growing presence of military groups and their role in arms and people smuggling. The US contribution to French operations has been limited to intelligence support, while Germany and the UK showed little-to-no interest in France’s military-prioritised approach to the multi-layered crisis.

The French-led Operation Barkhane succeeded Operation Serval in August 2014, but with a much wider geographic focus. France sent troops into Mali in 2013 to help drive back Islamist insurgents who had seized the north of the country. But attacks have continued since then, and the conflict has since spread to the country's center as well as to neighboring Burkina Faso and Niger.

In the Malian capital, Bamako, protests erupted in late 2019, with demonstrators holding up signs proclaiming, “France dégage” – France get out – amid mounting frustration over the deteriorating security situation in the West African nation. Protests against France, the former colonial power, spread from Mali to Burkina Faso and Niger in recent months and are sometimes expressed in creative ways. “Everywhere in the region, opposition movements and groups are demanding the French presence is imperialist or neo-colonial. They tend to think that as soon as there is a difficulty on the ground, it is France’s fault,” French President Emmanuel Macron said 23 December 2019 in Niger’s capital city. “President Issoufou clearly reminded us in what capacity France has intervened at the express demand of the Nigerien state. In other words, sovereign figures think that they need French support through Operation Barkhane.” Groups opposing the French-backed militarisation of the country use anti-colonial language from an Islamic perspective, and their message is: you have to chase the French coloniser who hates Islam.

The conflict in Mali involves several players, including the Malian army, which relies on support from the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), as well as French forces with the tacit support of the US and the UK, and other allies. These forces up until very recently were pitted against various violent groups – like the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA) and Ansar Al Dine (AAD) – but those have now united under Jama'a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin (JNIM), or the Group to Support Islam and Muslims. This group also includes members of Al Qaeda in the Maghreb (AQIM), under the leadership of Iyad Ag Ghali, a historical Tuareg fighter (and member of MNLA) and who has pledged allegiance to the Taliban and Ayman Mohammed Rabie al Zawahiri.

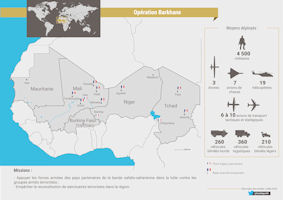

France made an early commitment to support the bordering states of Lake Chad in their fight against terrorism. On a political level, with the first Conference ever organized on the issue with the countries of the region, held in Paris in May 2014 and chaired by the President of the Republic, François Hollande; On the ground, with the action of the French armed forces of Operation Barkhane. Launched in August 2014, Operation Barkhane aims to provide logistical and intelligence support to countries in the region in the fight against terrorism. Barkhane supports the countries of the Sahel-Saharan strip grouped within the "Sahel G5" for a regional response to the security challenges and the terrorist threat.

In this context, France was a strategic partner, with 4,000 deployed troops in Gao (Mali) and N’Djamena (Chad). The force, with approximately 4,500 soldiers, was spread out between Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, and Chad. With headquarters was in N’Djamena, Chad’s capital, it also has combat aircraft and intelligence collection and operations in Niger’s capital Niamey, Agadez, Arlit, Tillabéry, and several other sites, as well as around 1,500 troops in northern Mali scattered between the large base at Gao, others at Kidal, Timbuktu, and Tessalit, and more recently a base at Gossi closer to central Mali as well as the border with Burkina Faso. France’s Special Operations Task Force for the region, Operation Sabre, was in Burkina Faso.

Operation Barkhane aims to:

- support the armed forces of the partner countries in their actions to combat terrorist armed groups;

- strengthen the coordination of international military capabilities;

- prevent the reconstruction of terrorist sanctuaries in the region.

Launched on 01 August 2014, Barkhane was an operation led by the French armies in the Sahel-Saharan strip. It relies on a local approach built on the partnership with the G5 Sahel countries to fight against Terrorists armed groups (GAT). The sahelian strategy of France aims to ensure that partner states acquire the capacity to ensure their safety independently. It was based on a global approach (political, security and development) whose military component was carried by Operation Barkhane, conducted by French arm.

The Saharan dunes are deformed under the influence of the wind, but they are but slightly displaced; in order for the sand to accumulate topographical conditions are required which are very definite; but which are, as yet, but little known. Only the sand itself is mobile. Ananogous conditions are to be found in the clouds, which persist in hanging around certain mountains for a long time in spite of the wind; the water vapor moves constantly, but does not become condensed except around the summit of the mountain. To prove the great mobility of the dunes some authorities have often cited the actual burying by sand of villages and oases, without reflecting that the planting of palm trees and the building of houses created the obstacles which supported the sand. The Saharan dunes show very varied arrangements. The growing dunes, the Barkhane, which is often mentioned as the typical form of the dune, is rare, and appears to be, on the contrary, an accidental form.

Barkhane's effort was focused on direct fight against the terrorist threat, the support of the partner forces, the supportinternational forces and actions in favor of the population in order to allow a gradual return to normal in areas where state authority was in question. The Barkhane force has the ability to conduct continuously and simultaneously operations throughout its area of action, which extends over the G5 Sahel countries. It's about a an area as vast as Europe: the distance between Niamey and N'Djamena was equivalent to the distance between Brest and Copenhagen.

Operation Barkhane was the successor to Operation Serval that started in January 2013, and the Operation Epervier that had been active in Chad since 1986. Around 3,000 soldiers were deployed to four bases in five different countries: headquarters and air force in the Chadian capital of N’Djamena under the leadership of French Général Palasset; a regional base in Gao, north Mali, with at least 1,000 men; a special-forces base in Burkina Faso’s capital, Ouagadougou; an intelligence base in Niger’s capital, Niamey, with over 300 men; the air base of Niamey, with drones for gathering intelligence across the entire Sahel-Saharan region.

Since these two ground control points, detachments are deployed on advanced temporary bases (BAT). The air assets’ employment – except the detachments of the Army light aviation (ALAT) and the Special Forces airplanes – was planned from Lyon by the JFACC AFCO (Joint Force Air Component Command for the Centre and the West of Africa).

Gathered since February 2014 into an institutional frame called “G5 Sahel”, Mauritania, Mali, Niger, Chad and Burkina Faso have decided to face the security challenges and the cross-border terrorist threat in coordination with the French troops and their support.

The operation was characterized by a logic of pooling and sharing of the means that used to be devoted to distinct operations (Serval in Mali, launched in 2013 and Epervier in Chad, launched in 1986). The presence of the French forces was maintained in Mali as well as in Chad, but from now on, the assets in these countries are shared and the areas of operations are extended to the whole Sahel-Saharan strip.

Operation Barkhane was based on a partnership approach with the main countries of the Sahelo-Saharan band (BSS). It aims primarily to promote country ownershipG5 Sahel partners in the fight against terrorist armed groups (GAT), on the entire Sahelo-Saharan band (BSS). This partnership logic structures Barkhane's relations with the others forces engaged in the stabilization process in Mali and the Liptako-Gourma ("Three Borders" zone): MINUSMA, EUTM Mali and the Armed Forces countries concerned.

The G5 Sahel brings together five countries of the Sahel-Saharan Africa : Burkina-Faso, Mali, Mauritania, Niger and Chad. Created in February 2014 at the initiative of the Heads of State of theregion, the G5 Sahel was an institutional framework for monitoring regional cooperation, aimed atcoordinate the development and security policies of its members.

In February 2017 the G5 countries announced the creation of a G5 Sahel joint forceagainst terrorism. July 2, 2017 in Bamako, on the occasion of a G5 Sahel summit realized in the presence of the President of the French Republic Emmanuel Macron, the chiefs of Mauritania, Niger, Chad, Mali and Burkina Faso formally announced its establishment. This force, which completed its first operation in November 2017 and will be 5,000 men was responsible for combating terrorism andcriminal organizations.

The integrated multidimensional United Nations Mission for Stabilization in Mali (MINUSMA) established by United Nations Security Council Resolution 2100 on 25 April 2013, was a major player in the resolution of the conflict in northern Mali. It was for France a privileged partner. The military component of MINUSMA was structured around a staff based at Bamako and about twenty units deployed in Mali. About twenty French are inserted in this staff and in the staffs of sectors in Gao, Kidal and Timbuktu. The Chief of Staff of MINUSMA was occupied by a Frenchman.

The European Training Mission of the Malian Army (EUTM Mali) was launched on 18 February 2013, following the adoption of UN Security Council Resolution 2085. It was part of the overall approach of the European Union to strengthen security in Mali and the Sahel. It has a staff of about 600 from around 20 Member States, including a dozen French soldiers.

Operation Barkhane was the most important French deployment in external operations. Since 2014, more than 1,000 operations and patrols have been carried out throughout the Sahelo-Saharan strip. France’s commitment was to enable partner States to acquire the capacity to ensure their security autonomously. To this end, Barkhane’s support for the actions of partner forces in the fight against terrorism was accompanied by joint operations and training activities with these forces.

France's strategy in the Sahel was based on a global approach, of which Barkhane was the military component. This global approach combines defense, development and diplomacy, and requires solid coordination between the various French players.

On 03 February 2019, French jets attacked a convoy of heavily armed pickup trucks that had entered Chad from neighboring Libya. The strikes lasted four days. When French fighter jets bombarded 40 pickup trucks of suspected insurgents in Chad, the former colonial power signaled an unprecedented willingness to engage openly in joint military operations in Northern Africa.

Chadian opposition leaders questioned whether the airstrikes were intended to fight terrorism or prop up President Idriss Déby, who has led Chad for nearly 30 years. “The French launched the airstrikes themselves, and they did not even try to make it seem as if they were not interfering with Chadian politics,” said Marielle Debos, an associate professor at Paris Nanterre University. Debos, who has researched the country for more than a decade, said in the past the French army’s support has been more discreet.

France said it had responded to a request for assistance from the Chadian government, calling the country an essential partner in the fight against terrorism. Chadian officials said the attacks were legal and necessary to prevent terrorist activity.

France’s interests in the region are primarily economic. Their military actions protect their access to oil and uranium in the region – all of which are required to sustain the demands of consumerism. French energy giants like Total control many of the downstream oil distribution networks in Mali, which arise in the Taoudeni Basin, a massive oilfield that stretches 1,000 km (600 miles) from Mauritania across Mali and into Algeria.

An incredible 75 percent of France's electric power was generated by nuclear plants that are mostly fuelled by uranium extracted on Mali's border region of Kidal – a region beset with violence between French-backed troops and forces of Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM). Mali was Africa’s third largest gold producer, and there are several multinational mining companies, including Randgold (UK), AngloGold Ashanti (South Africa), B2Gold (Canada) and Resolute Mining (Australia), that have huge operations there.

Researcher Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Montclos, author of the book "A lost war. France in the Sahel", believes that "Operation" Barkhane "prolongs the life of corrupt regimes". For Marc-Antoine de Montclos there was immediately a risk of returning to the heyday of Françafrique, a risk of sinking, an extreme danger for a former colonial power to replace the state and the army. He told Le Monde "France kicked the anthill of jihadist groups. The result was that they dispersed and then emerged in areas where they were not before, such as northern Burkina Faso or Macina, in central Mali. We therefore observe rather an extension of the phenomenon. And these groups, which were fragmented and did not necessarily get along, regrouped, with now a common enemy: France. The foreign military presence gives them legitimacy.... . To win an asymmetrical war against an invisible enemy, you need the support of the people. This was impossible to obtain if, in the name of the fight against terrorism, the abuses committed by the African soldiers are allowed to pass.... With this insurance policy offered to them by the French army, all these plans have no incentive to reform."

“The presidents of the G5 Sahel countries have a dilemma,” noted Pérouse de Montclos. “On one side, they need a French military presence – also against their own security forces to prevent coups and mutinies. But at the same time, they can’t say that publicly because it’s a humiliation, a shame for Africans that so many decades after independence, they still need the French army to stabilise their own countries.”

France will deploy 600 more soldiers in the fight against Islamists militants in Africa’s Sahel, south of the Sahara, French Defence Minister Florence Parly said on 02 February 2020. The reinforcements would mostly be sent to the area between Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, Parly said in a statement. Another part would join the G5 Sahel forces. Parly added that Chad “should soon deploy an additional battalion” within the joint force of the G5 Sahel, which brings together Mauritania, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger and Chad in the three borders zone. It’s the epicenter of the fight against jihadist groups, including the Islamic State group in the Grand Sahara (ISIS-GS). “The reinforcement ... should allow us to increase the pressure against the ISIS-GS... We will leave no space for those who want to destabilise the Sahel,” she added.

France already had 4,500 soldiers stationed in the Europe-sized region as part of Operation Barkhane, supporting poorly-equipped, impoverished local armies that in 2017 launched a joint anti-jihadist G5 Sahel force. Despite the French presence and a 13,000-strong UN peacekeeping force dubbed MINUSMA in Mali, the conflict that erupted in the north of that country in 2012 had since spread to its neighbors, especially Burkina Faso and Niger.

A hundred jihadists were killed this month in a joint Franco-Malian offensive in the West African country's lawless centre, the Malian army said 26 January 2021. One hundred terrorists were neutralised, about 20 captured and several motorbikes and war equipment were seized during the operation with France's Barkhane force, which aims to eradicate jihadists in the Sahel region, the Malian army said.

The French anti-terror mission Barkhane was losing support in Mali, as reflected in protests in the capital, Bamako in January 2021. Attitudes to the former colonial power are ambivalent amid deteriorating security. The security situation has worsened, with not only the north but also central Mali now affected. There were a number of militant groups active in the Mopti region, including "self-defense militias with their own agenda." Farmers could no longer cultivate their fields and that entire villages had fled the region, some 630 kilometers (390 miles) northeast of Bamako. There are also reports of bandits setting up roadblocks and attacking travelers in the Timbuktu region. The resulting fear and mistrust was threatening stability and development.

Oumar Mariko, the secretary-general of the left-wing political party African Solidarity for Democracy and Independence (SADI), international missions are not the solution. At a press conference at SADI headquarters in Bamako, he received a huge round of applause from supporters after stating: "Our philosophy is: Only the Malians themselves can end this conflict. In Kidal, Gao and Timbuktu, Malians themselves have taken up arms and are using them in the name of Islam." Mariko favors promoting dialogue between the different stakeholders. When asked why his party had not had any success with this method up until now, he shrugged his shoulders and responded: "We cannot propose any solutions because we're not in power."

Malian officers criticize the fact that the European Union Training Mission in Mali was too theoretical. On the other hand, one hears international officers saying that it was not easy to implement training missions with Malian troops. The international missions in Mali have also been criticized because their mandate was not always clear to the population. The task of the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), the biggest peacekeeping mission in the country with 13,000 troops, was to implement a 2015 peace agreement and to stabilize the north. However, it has come under fire in the past for not intervening when conflict emerges in other parts of the country. In fact, it was legally not permitted to do so, but this was not generally understood.

Many Malians see France as being a natural partner both in linguistic and cultural terms, while at the same time often being very critical of the military operations.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|