Anti-War Movement

A growing American casualty list and the uncertain prospects of driving Hanoi out of the war gradually converted the near-unanimous approval of the 1964 Tonkin Gulf Resolution into widespread Congressional and popular opposition to the war. Doves became angry. Anti-war demonstrations took place in the cities of San Francisco and Chicago.

A growing American casualty list and the uncertain prospects of driving Hanoi out of the war gradually converted the near-unanimous approval of the 1964 Tonkin Gulf Resolution into widespread Congressional and popular opposition to the war. Doves became angry. Anti-war demonstrations took place in the cities of San Francisco and Chicago.

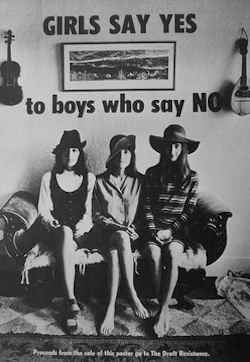

More and more students began to protest. They wanted the war to end quickly. Doves became angry. Anti-war demonstrations took place in the cities of San Francisco and Chicago. More and more students began to protest. They wanted the war to end quickly. Opposition to the war and to the Administration's war policies led to bigger and bigger anti-war demonstrations. Studies were done to measure Americans' opinion on the issue. In a study in July 1967 a little more than half the people questioned said they did not approve of the President's policies.

After the October, 1967, demonstration at the Pentagon, House Democratic fioor leader Carl Albert said the marchers included "every Communist and Communist sympathizer who was able to make the trip." He also charged that the demonstration had been "basically organized by international communism." Republican floor leader Gerald Ford then revealed that at a White House meeting President Johnson had read to him and other Republican leaders a secret report revealing that the demonstration was organized by international communism. He asked that the report be made public. Attorney General Ramsey Clark visited Ford and said the report could not be revealed without compromising sources of information and creating a new wave of "McCarthyism." This claim was also made by Secretary of State Dean Rusk. Ford argued that the American people were mature enough to receive such information without reacting hysterically.

Under pressure from the Johnson and Nixon White Houses to determine whether there was "foreign influence" behind anti-war protests and black militant activity, the CIA began collecting intelligence about domestic political groups. Joseph Califano, a principal assistant to President Johnson, testified to the Senate Intelligence Committee 27 January 1976, that high governmental officials could not believe that "a cause that is so clearly right for the country, as they perceive it, would be so widely attacked if there were not some [foreign] force behind it." CIA Director Richard Helms testified that the only manner in which the CIA could support its conclusion that there was no significant foreign influence on the domestic dissent, in the face of incredulity at the White House, was to continually expand the coverage of CHAOS. Only by being able to demonstrate that it had investigated all anti-war persons and all contacts between them and any foreign person could CIA "prove the negative" that none were under foreign domination.

CIA reported 15 November 1967 "Diversity is the most striking single characteristic of the peace movement at home and abroad. Indeed it is this very diversity which makes it impossible to attach specific political or ideological labels to any significant section of the movement. Diversity means that there is no single focus in the movement. Joint action on an international scale is possible only because coordination is handled by a small group of dedicated men, most of them radically oriented, who have voluteered themselves for active leadership in the key organizations.... Apart from contacts with the Hanoi officialdom, US peace activists by and large do not deal with foreign governments.... Moscow exploits and may indeed influence the US delegates ... through its front organizations, but the indications — at least at this stage — of covert or overt connections between these US activists and foreign governments are limited.

The main mechanism for coordinating both domestic and foreign protest activity related to Vietnam was been the "mobilization committee" [the "mobe"]. Out of the Student Mobilization Committee of 1966 evolved the Spring Mobilization Committee (SMC), which in turn was succeeded by the present National Mobilization Committee (NMC). The officers appointed to the executive bodies of the NMC were numerous, reflecting the coalition's broad base, but the real responsibility seemed to be concentrated in the hands of a few. The names of these key coordinators turned up regularly, wherever the action happens to be.

David Dellinger, the leading US peace activist, stated in May 1963 that he was "a Communist, but not of the Soviet type, ” according to an FBI source. Although never a member of a political party, Dellinger had been continuously associated with pacifist organizations since the 1930 ’s and later with the Trotskyite Socialist Workers Party and various Communist front groups. He was also noted for his involvement in pro-Castro organiza tions.

Close personal coordination between US activists and the North Vietnamese appears to have begun in 1965. The DRV at that time invited Herbert Aptheker, prominent CPUSA theoretician and Director of the American Institute for Marxist Studies, to visit Hanoi. Aptheker in turn suggested that he be accompanied by Staughton Lynd, former Yale Professor and a leader of the US Committee for Non—Violent Action (CNVA), and Thomas Hayden, a militant civil rights worker and a founder of the SDS. The trio visited Hanoi in December 1965.

The NMC, principal sponsor of the October 1967 peace demonstration in Washington, was a direct outgrowth of the Spring Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam (SMC). SMC was formed to coordinate the demonstration in April 1967 against the Vietnam War and the draft. The NMC was not an action group. It is a coordinating outfit responsible for disseminating information and literature to other peace groups and to the public at large. It coordinated demonstrations, obtained necessary permits, negotiated with civil authorities for facilities, and provides legal assistance when needed. Except for the few paid professional executives, the NMC can be categorized simply as a collection of local peace groups.

Communist penetration of the organization was apparent at several levels, but the NMC was so diversified in its make-up and organizationally loose, that it was not an easy mark for classic Communist manipulation. Many members of the NMC leadership, including Chairman David Dellinger and Vice Chairman Jerry Rubin, hade known and associated with Communists and Communist-front groups over the years. Both Dellinger and Rubin were also strong supporters of Castro and his movement.

The "American peace "movement" was not one but many movements; and the groups involved are as varied as they are numerous. The most striking single characteristic of the peace front is its diversity.... Under the peace umbrella one finds pacifists and fighters, idealists and materialists, internationalists and isolationists, democrats and totalitarians, conservatives and revolutionaries, capitalists and socialists, patriots and subversives, lawyers and anarchists, Stalinists and Trotskyites, Muscovites and Pekingese, racists and universalists, zealots and nonbelievers, puritans and hippies, do—gooders and evildoers, nonviolent and very violent. One thing brings them all together: their opposition to US actions in Vietnam.

"As a result of their infiltration of the leadership of key peace groups, the Communists manage to exert disproportionate influence over the groups' policies and actions. It remains doubtful, however, that this influence is con- trolling. Most of the'Vietnam protest activity would be there with or without the Communist element. The CPUSA, in other words, is exploiting and benefiting from anti—government activity, but it does not appear to be inspiring it or directing it."

FBI reporting on protests against the Vietnam War provides an example of the manner in which the information provided to decision-makers can be skewed. In acquiescence with a judgment already expressed by President Johnson, the Bureau's reports on demonstrations against the War in Vietnam emphasized Communist efforts to influence the anti-war movement and underplayed the fact that the vast majority of demonstrators were not Communist controlled.

R.L. Shackleford, an FBI Intelligence Division Section Chief, told the Senate Intellgence Committee 13 February 1976 that he could not "think of very many" major demonstrations in this country in recent years "that were not caused by" the Communist Party or the Socialist Workers Party. In response to questioning, the Section Chief listed eleven specific demonstrations since 1965. Three of these turned out to be principally SDS demonstrations, although some individual Communists did participate in one of them. Six others were organized by the National (or New) Mobilization Committee, which the Section Chief stated was subject to Communist and Socialist Workers Party "influence." But the Section Chief admitted that the mobilization Committee "probably" included a wide spectrum of persons from all elements of American society. The FBI had not alleged that the Socialist Workers Party was dominated or controlled by any foreign government.

The 1969 "fall offensive" that brought thousands of protesters to Washington in October and November 1969 involved four organizations: The Vietnam Moratorium Committee, the Student Mobilization Committee, the New Mobilization Committee [New MOBE], and the SDS. The purpose of the fall offensive was to pressure the administration into an immediate, unilateral withdrawal of American troops from Vietnam.

From birth, Student Mobe had been a united front organization, a combine of various groups, many openly Communist, uniting their efforts to draw as many youths as possible into the anti-Vietnam War movement. In mid-1968, however, an important change took place. As a result of a long-simmering feud, the CPUSA element walked out in a huff, leaving the young "Trots" in command. As J. Edgar Hoover stated in 1969, Student MOBE "is controlled by members of the Young Socialist Alliance, the youth group of the Socialist Workers Party." Since its formation, Student MOBE had served as the right arm of the name-changing adult MOBE, organizing student support for Vietnam Week, the Pentagon confrontation, etc..

Over 500,000 Americans joined in October 1969 in a "moratorium" to oppose the U.S. military involvement in South Vietnam. A month later, the largest antiwar demonstration in the history of the United States, staged for the same purpose, took place in Washington itself. The national moratorium, with millions participating in the largest anti-war demonstration in a western democracy, The American flag at the Department of Justice was pulled down and - if only briefly - replaced by the flag of the Viet Cong. On the same day, Nov. 15, anti-US-in-Vietnam demonstrations took place in many nations. This was no coincidence. It was all carefully coordinated.

The New Mobilization Committee, technically the sponsor of the Nov. 15 Washington demonstrations, made many statements that it decried violence and wanted only a peaceful, orderly demonstration. The Student Mobilization did the same thing. The Moratorium Committee had always taken that position. SDS also promised it would not "instigate" violence.

There just aren't enough full-fledged communist party members in this country - even including the Muscovites, the Pekingese, the Trotskyists and all the splinter groups together - to put on a demonstration of such proportions that it could have national and international importance. They enlisted non-Communists in their operations - many of them: the 100 percent fellow travelers who can always be counted on to rally to the cause, as well as the lesser fellow travelers who respond on certain issues; the independent radicals and extremists, the non-party Marxists, the pacifists (particularly useful for "peace" operations), the malcontents and anyone else they can coax, cajole or hoodwink into working for their cause. It should be stressed, however, that New MOBE was not a Communist "front" in the traditional sense of the term.

The announcement by President Nixon on the evening of April 30, 1970, that he had authorized a joint US.-South Vietnamese incursion into Cambodia provoked an instant public backlash and revitalized an anti-war movement that had been steadily losing support among the wider population as a result of students' increasingly violent and destructive tactics.

May 1970 saw the start of a three-week period of protests and demonstrations on university campuses across the nation, culminating on May 4 with the death of four demonstrators at the hands of National Guardsmen at Kent State University. The eruption of student protest throughout the country was unprecedented. With over half of the more than 2,500 universities and colleges experiencing some form of anti-war protest, and an estimated 1.5 million students taking part, it represented the largest series of mass demonstrations in US history.

Despite the deaths of demonstrators at Kent State and at Jackson State University in Mississippi ten days later, the protests that touched college campuses in May 1970 were overwhelmingly peaceful. According to one study, of the some 1,350 colleges and universities that saw anti-war demonstrations during that month, only seventy-three witnessed violence of any form.

The events of May 1970 at universities across the nation were the last great gasp of the student anti-war movement. With students departing for the summer, campuses became quiet again. The Cambodian incursion and resulting protests had breathed new life into a movement that had been on life support, but the momentum that had arisen so quickly was just as suddenly stalled. As one historian puts it, the student movement "never recovered from the summer vacation of 1970."

Large-scale actions still occurred—in April 1971, more than half a million people convened in Washington for a peace demonstration, the second largest gathering to occur there. But by this time the American public had largely turned against the war, and though the U.S. would not officially extricate itself from Vietnam until January 27, 1973, it looked to many as though the war was finally winding down. With most of the country now holding the formerly radical position that the United States must get out of Vietnam, and with an end to the conflict in sight, demonstrations and protests gradually withered away.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|