Cahokia

Cahokia was destroyed by the effects of climate change, undermined by Global Cooling. One of the greatest cities of the world, the population of Cahokia was larger than that of London in AD 1250. Occupied from 700 to 1400 AD, the city grew to cover 4,000 acres [about 1600 hectares]. For scale compariton, The founding of Yanshi city marked the fall of the Xia Dynasty (2100 - 1600 BC) and the start of the Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 BC). Ruins were found at the site of a city measuring 1,700 meters in length from north to the south, and 1,200 meters wide from east to the west [200 hectares]. The population of 20,000 to 30,000 at Cahokia (AD 650–1400) equals that of the ancient Mesopotamian city-states of Ur or Babel.

Cahokia was destroyed by the effects of climate change, undermined by Global Cooling. One of the greatest cities of the world, the population of Cahokia was larger than that of London in AD 1250. Occupied from 700 to 1400 AD, the city grew to cover 4,000 acres [about 1600 hectares]. For scale compariton, The founding of Yanshi city marked the fall of the Xia Dynasty (2100 - 1600 BC) and the start of the Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 BC). Ruins were found at the site of a city measuring 1,700 meters in length from north to the south, and 1,200 meters wide from east to the west [200 hectares]. The population of 20,000 to 30,000 at Cahokia (AD 650–1400) equals that of the ancient Mesopotamian city-states of Ur or Babel.

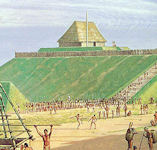

Cahokia, in modern-day Illinois, was once the largest indigenous urban center in what is now the United States, before the arrival of European explorers. Cahokia's population around the year 1200 AD was larger than that of any city in American colonies prior to Independence. With pyramids, mounds, and several large ceremonial areas, Cahokia was the hub of a way of life for millions of Native Americans before the society's decline and devastation by foreign diseases.

A global cooling trend about 1250, called the "Little Ice Age," may have hurt the growing season. An unusual, 50-year-long episode of four massive tropical volcanic eruptions brought the onset of the Little Ice Age. Climate models showed the persistence of cold summers following the eruptions is best explained by a sea ice-ocean feedback system that originated in the North Atlantic.

Since glacier ice contains almost no salt, when it melted the surface water became less dense, preventing it from mixing with deeper North Atlantic water. This weakened heat transport back to the Arctic and creating a self-sustaining feedback system on the sea ice long after the effects of the volcanic aerosols subsided. Livestock died, harvests failed, and humans suffered from the increased frequency of famine and disease.

The name "Cahokia" is a misnomer. It comes from the name of a sub-tribe of the Illini who didn't reach the area until the 1600s, coming from the East. The original complex of mounds, homes, and farms, covered over 4000 acres. Population estimates for Cahokia proper range from 10-20,000. If East St. Louis, St. Louis and other surrounding sites are included, then a population of 40-50,000 is possible for "Greater Cahokia."

Although the exact cause of the decline of Cahokia is not obvious, it is clear that several different events contributed to its downfall. Overpopulation of the area was a definite factor in Cahokia's demise.

Larry Benson et al argue that the " rapid development occurred during one of the wettest 50-year periods during the last millennium. During the next 150 years, a series of persistent droughts occurred in the Cahokian area which may be related to the eventual abandonment of the American Bottom. By A.D. 1150, in the latter part of a severe 15-year drought, the Richland farming complex was mostly abandoned, eliminating an integral part of Cahokia's agricultural base. At about the same time, a 20,000-log palisade was erected around Monks Mound and the Grand Plaza, indicating increased social unrest. During this time, people began exiting Cahokia and, by the end of the Stirling phase (A.D. 1200), Cahokia's population had decreased by about 50 percent and by A.D. 1350, Cahokia and much of the central Mississippi valley had been abandoned. "

The American Bottom is a tract of rich alluvian land, extending on the Mississippi, from the Kaskaskia to the Cahokia river, about eighty miles in length and five in breadth; several handsome streams meander through it; the soil of the richest kind, and but little subject to the effects of the Mississippi floods. If any vestige of ancient population were to be found, this would be the place to look for it. Accordingly, this tract, as also the bank of the river on the western side, exhibit proofs of an immense population.

The property is owned by the State of Illinois and designated by Illinois law as a State Historic Site specifically for its preservation and public interpretation. The core of the State Historic Site has been preserved as a protected public site since 1925. Its archaeological resources are further protected by State law and regulation.

Within the boundaries of the property are located the main elements necessary to understand and express the Outstanding Universal Value of Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site, including the central mounds, the palisade, most of the “Woodhenge” and the functional areas. All three types of mounds are preserved, as well as borrow pits. The course of the palisade remains almost completely intact. Large areas adjacent to the core of the site have been acquired, reclaimed from development, and restored to preserve the historic setting. The property is thus of sufficient size to adequately ensure the complete representation of the features and processes that convey the property’s significance, and it does not suffer from adverse effects of development and/or neglect.

Brackenridge's description, written in 1811 and published in 1814, observed as did Flagg a great number of artifacts strewn over the surface and that there were many small elevations which have probably since disappeared. What impressed him, as well as the others of those early days, was not only the charm and mystery of the mounds themselves but their pleasant location in the Great Plain and that this plain was not entirely a prairie but broken here and there by clumps of heavy vegetation and ponds of water.

The archaeological record begins with hunting and gathering peoples of the late Pleistocene epoch during the last phases of the Ice Age. They hunted mammoths and bison as well as deer, and collected fruits and plants in season. Their stone axe heads and other objects show a high level of symbolic activity. The largest known settlement, located on the banks of the river Bayou Maçon in northeastern Louisiana, was anchored by a fifty-foot-high ceremonial mound aligned to the sun's path.

Around 500 BC central Ohio became a center of new cultural activity. The Adena people built conical mounds to commemorate tribal leaders, and their practices were expanded by the Hopewell culture, which existed between the years 1 and 400 AD. The Newark Earthworks is perhaps the best known. The site encompassed four square miles and included two giant circles, an ellipse, a square, and an octagon, all connected by parallel walls.

The Hopewell people had by this time expanded their artistic repertoire to specialized, supernatural figures such as the long-nosed god, the birdman, and the old-woman-who-never-dies. They employed exotic materials such as shell from the Gulf of Mexico, copper from present-day Michigan, mica from what is now North Carolina, and obsidian from the land that became Wyoming. The Hopewell people eventually spread westward to the Illinois River Valley and into Tennessee, where the Mississippian period began some time after 800 AD. Cahokia was built near where the Missouri, Ohio, and Illinois rivers empty into the Mississippi.

As the region's capital, Cahokia was replete with flat-top pyramids, burial mounds, and a vast ceremonial concourse surrounded by commercial and residential areas as well as outlying agriculture zones. The central mound grew to a height of one hundred feet -- the largest mound north of the valley of Mexico.

Cahokia Mounds was the regional center for the American Indian Mississippian culture, resembling a modern metropolis with its complex social system and large, permanent, central towns. Cahokia Mounds World Heritage Site represents a truly unique example of the complex social and economic development of pre-contact indigenous Americans.

Monks Mound measures 304 meters (1000 feet) by 213 meters (700 feet) at its base and covers 5.7 hectares (14 acres), rising to approximately 100 feet in a series of four terraces. The Great Pyramid of Khufu/Cheops at Giza is about 750 feet on a side. There is a long or gentle slope or "feather" edge at the base of the mound, on all sides. One observor might differ 30 to 50 ft. from another investigator as to where the mound actually began. Dominating the community was Monks Mound, the largest prehistoric earthen structure in the New World. Constructed in fourteen stages, it covers six hectares and rises in four terraces to a height of 30 meters.

The earthen mounds at Cahokia offer some of the most complex archaeological sites north of Central Mexico. Monks Mound, which dominates the World Heritage Site and is located near its center, is the largest manmade structure north of Central Mexico. This has for many years been called Monks Mound because of the presence of the Trappists during a short period between 1808-1813. It is much washed and weather-worn, and has lost a great deal of its original charm. In fact if one should compare the various views taken in the 1890s of the mound with a photograph of it in the 1920s, one would scarcely imagine the two to represent the same structure.

The city housed artisans, political embassies, and was a destination for religious pilgrims. Cahokians were ruled under matrilineal succession and practiced human sacrifice. The death of a leader required the sacrifice of the spouse and at times other family members.

The traditional model of a highly integrated, complex chiefdom with all power emanating from Cahokia requires a radical restructuring of earlier societies. According to this model less powerful chiefs throughout the American Bottom were quickly and totally supplanted by the Cahokia elite. The traditional model viewed the demise of Mississippian society throughout the American Bottom as a direct result of the collapse of Cahokia itself. In short, the traditional model is a top-down approach to understanding culture change.

The alternative model argues that the American Bottom supported several quasi-independent, but Cahokia-dominated, chiefdoms throughout the Mississippian Period. In this conservative model, developments did not involve a wholesale restructuring of society where Cahokia administrative institutions and functionaries implemented directives from the Cahokia paramount chief on smaller communities. Rather, the rise of the Cahokia-dominated complex chiefdom involved little more than the establishment of ties between the most important people(chiefs and their close kin) among the various chiefly elites and that of Cahokia.

Thus, this regional sociopolitical system, sometimes called a complex chiefdom, was little more than a linked series of simple chiefdoms, each of which was allied to the most powerful of them all, Cahokia. Accordingly, the conservative model views the demise of Cahokia as a consequence of a highly competitive and unstable social system in which household independence promoted by farming was mirrored in the shifting alliances among chiefdoms and a lack of integration into a monolithic Cahokia polity.

The city's enduring legacy came in the form of highly trained artisans who supplied works to chieftains and elites. Cahokian elites most likely used figurines crafted into pipes, shells inscribed with supernatural characters, stylized copper plates, and other items as a means to disseminate their beliefs to outlying communities, including the ancient chieftaincies at Etowah, Georgia; Spiro, Oklahoma; and Moundville, Alabama. The body of art produced at Cahokia spread far and wide, helping to perpetuate and reinforce the central myths and rituals common to the people at the time.

Contacts that Europeans made with Native Americans in this era set off a wave of catastrophic outbreaks of measles, smallpox, diphtheria, and even the common cold. More than 90 percent of Indian populations perished within a century. The Indian country most colonists found when they crossed the Appalachians lacked the sophistication of the Cahokia and the mound builders.

The Mississippian Period in Georgia was brought to an end by the increasing European presence in the Southeast. European diseases introduced by early explorers and colonists devastated native populations in some areas, and the desire for European goods and the trade in native slaves and, later, deerskins caused whole social groups to relocate closer to or farther from European settlements. The result was the collapse of native chiefdoms as their populations were reduced, their authority structures were destroyed by European trade, and their people scattered across the region.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|