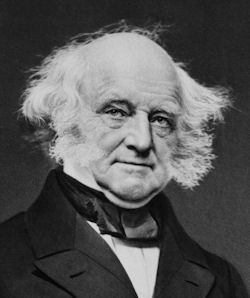

Martin Van Buren (1837-1841)

Politics before the Civil War was a whirlwind of opposing interest groups. Martin Van Buren was able to unite those groups becoming president in 1837. As frustration and violence over the extension of slavery grew in the 1840's, Van Buren ran for the presidency twice more. He hoped to unite sectional interests but failed; ultimately so did the union.

Politics before the Civil War was a whirlwind of opposing interest groups. Martin Van Buren was able to unite those groups becoming president in 1837. As frustration and violence over the extension of slavery grew in the 1840's, Van Buren ran for the presidency twice more. He hoped to unite sectional interests but failed; ultimately so did the union.

Born December 5, 1782 six years after the colonies declared independence from Britain, Martin Van Buren was the first president born in the new United States of America. He attended village schools and became a law clerk at age fourteen, going on to study law and to join the bar in 1803. Van Buren studied and practiced law in New York. After moving to Hudson, New York, Van Buren served as the Surrogate of Columbia County from 1808 to 1813. He entered politics with election to the State Senate, where he served from 1813 to 1820. He then became the New York Attorney General from 1816 to 1819. Van Buren next won election to the United States Senate, serving from 1821 to 1828, and became Governor of New York in 1829.

Van Buren earned the nickname "The Little Magician” because of his height and his political shrewdness. Bbetween 1817 and 1821 he put together a political machine beyond anything that had ever existed in the United States. Then, in 1827, with a new presidential election approaching, Van Buren placed his powerful political machinery behind the candidacy of Andrew Jackson.

He resigned as Governor to join the Cabinet of President Andrew Jackson as Secretary of State. Following his three years as Secretary, Van Buren was elected Vice President under Jackson and served from 1833 to 1837. Van Buren was the prime architect of the Democratic Party coalition that helped elect Andrew Jackson, and he served as his secretary of state and later vice president. He emerged as President Jackson's most trusted adviser. Jackson referred to him as, "a true man with no guile," but others called him “The Fox of Kinderhook” for his skill at backstage political maneuvering. According to one observer, Van Buren “rowed to his object with muffled oars.”

Martin Van Buren was appointed Secretary of State by President Andrew Jackson on March 6, 1829. Van Buren served in that capacity from March 28, 1829, to March 23, 1831. He was an astute career politician who approached foreign affairs with caution. Jackson provided Van Buren an entrée to foreign affairs. Jackson selected Van Buren as Secretary of State as a reward for Van Buren’s efforts to deliver the New York vote to Jackson.

As President, Jackson was hesitant to relinquish control over foreign policy decisions or political appointments. Over time, Van Buren’s ability to provide informed advice about domestic policies, including the Indian Removal Act of 1830, won him a place in Jackson’s circle of closest advisers.

Van Buren’s tenure as Secretary of State included a number of successes. Working with Jackson, he reached a settlement with Great Britain to allow trade with the British West Indies. They also secured a settlement with France, gaining reparations for property seized during the Napoleonic Wars. In addition, they settled a commercial treaty with the Ottoman Empire that granted U.S. traders access to the Black Sea. However, Jackson and Van Buren encountered a number of difficult challenges. They were unable to settle the Maine-New Brunswick boundary dispute with Great Britain, or advance the U.S. claim to the Oregon territory. They failed to establish a commercial treaty with Russia and could not persuade Mexico to sell Texas.

Van Buren resigned as Secretary of State due to a split within Jackson’s Cabinet in which Vice President John C. Calhoun led a dissenting group of Cabinet members. Jackson acquiesced and made a recess appointment to place Van Buren as U.S. Minister to Great Britain in 1831. While in Great Britain, Van Buren worked to expand the U.S. consular presence in British manufacturing centers. His progress was cut short when the Senate rejected his nomination in January of 1832.

Van Buren returned to the United States and entered presidential politics, first as Jackson’s Vice President and then as President. While serving as chief executive, Van Buren proceeded cautiously regarding two major foreign policy crises. At the time of Van Buren’s inauguration, the country seemed prosperous, but less than three months later the panic of 1837 began. Hundreds of banks and businesses failed. Thousands lost their lands. For six years, the United States struggled with the worst depression thus far in its history. Van Buren's continuance of Jackson's deflationary policies only deepened and prolonged the depression.

Critics charged that it was Andrew Jackson's destruction of the U.S. Bank that had led to the crash, and that a new national bank was now needed to reverse it. Determined not to depart from his predecessor's key commitment, Van Buren presented a counterproposal -- the establishment of an independent Treasury. In a striking act of presidential leadership, he united his critics around a new course of action. Van Buren's idea for an independent Treasury would be the central accomplishment of his presidency, preparing the way for what would become the backbone of the U.S. financial system for the next seventy years. In the short-run, however, Van Buren prolonged the recession and deepened it into a significant depression. The remedy he proposed was an independent Federal Government treasury system, which Congress refused to authorize until 1840.

The delay helped cement Van Buren’s defeat in his run for re-election. Van Buren was wary of worsening U.S. relations with Mexico. His opposition to the annexation of Texas further hurt his popularity in the West and South. Van Buren blocked the annexation because of the certainty that it would add to the slave territories and carried the threat of war with Mexico. Far from resolved, the issue would cause war and domestic turmoil over the next several decades. He worked to diffuse a potential breach with Great Britain when Maine farmers attacked across the northern border and when Canadians burned the U.S. vessel Caroline in the Niagara River.

The Van Buren administration also proved particularly hostile to Native Americans. Federal policy under Jackson had sought, through the Indian Removal Act of 1830, to move all Indian peoples to lands west of the Mississippi River. Continuing this policy, Van Buren supported further removals after his election in 1836. The federal government supervised the removal of the Cherokee people in 1838, a forced stagger west to the Mississippi in which a full quarter of the Cherokee nation died.

Some Native Americans resisted the removal policy violently, however. In Florida, the Seminole people fought upwards of 5,000 American troops, and even the death of the charismatic Seminole leader Chief Osceola in 1838 failed to quell the resistance. Fighting continued into the 1840s and brought death to thousands of Native Americans. The protracted nature of the conflict had deleterious political consequences too. The Whigs, as well as a small number of Americans who believed the removal campaign inhumane, criticized the Van Buren administration’s conduct of the war.

In 1844, Van Buren failed in a bid for the Democratic presidential nomination, and he ran unsuccessfully on the Free Soil (anti-slavery) ticket for presidential reelection in 1848. Increasingly opposed to slavery, Van Buren endorsed Lincoln's efforts to limit slavery and preserve the Union. Van Buren lived out the remainder of his life at Lindenwald until his death in 1862.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|