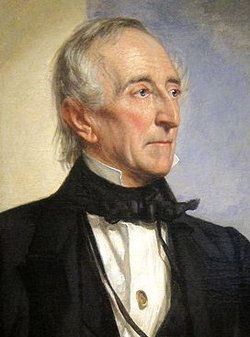

John Tyler (1841-1845)

John Tyler was 10th President of the United States, As the first vice president to become president after President William Henry Harrison died in office in 1841, Tyler set the precedent for vice presidents assuming the role and status of an elected president. Though he chaired a "Peace Convention" in Washington, DC in 1861 to try to prevent the Civil War, as a southern gentlemen and advocate of States rights, Tyler supported secession when that failed. The Virginia native served as a delegate to the Confederate Provisional Congress in 1861 and had been elected to the Confederate Congress at the time of his death on January 18, 1862.

John Tyler was 10th President of the United States, As the first vice president to become president after President William Henry Harrison died in office in 1841, Tyler set the precedent for vice presidents assuming the role and status of an elected president. Though he chaired a "Peace Convention" in Washington, DC in 1861 to try to prevent the Civil War, as a southern gentlemen and advocate of States rights, Tyler supported secession when that failed. The Virginia native served as a delegate to the Confederate Provisional Congress in 1861 and had been elected to the Confederate Congress at the time of his death on January 18, 1862.

John Tyler was born in 1790 at Greenway plantation, only about three miles away from Sherwood Forest. In early boyhood he attended an "old-field" school," and was graduated at William and Mary College in July, 1807. James Madison, the president of the college, and Judge Tyler had been college-mates of Thomas Jefferson, and the political principles of the rising statesman came naturally to favor "states-rights." At college he showed a strong interest in ancient history. He was also fond of poetry and music and was a skilful performer on the violin. In 1809, before attaining bis majority, he was admitted to the bar.

He was elected to the legislature and took bis seat in that body in December, 1811. He was here a firm supporter of Madison's election; and the war with Great Britain, which soon followed, afforded him an opportunity to become conspicuous as a forcible and persuasive orator. The bank bad always been unpopular in Virginia, but the Virginia senators at Washington ignored the instructions to the legislature and favored its re-charter in 1811.

Tyler married, March 20,1813, Letitia, daughter of Robert Christian, and a few weeks afterward was called into the field at the head of a company of militia, to take part in defence of Richmond, now threatened by the British. His military service lasted but a month. He was reelected to the legislature annually until, in November, 1816, be was chosen to fill a vacancy in the the United States House of Representative as a Democratic Republican.

Tyler supported the pro-slavery, strict constructionist, and states’ right positions that he would hold to for the rest of his career. He voted against the bill introduced by Calhoun in favor of internal improvements on the ground of its unconstitutionality and its lack of a principal of uniform application among the states.

In the debates over the admission of Missouri, Tyler took the ground that slavery was an evil, but that congress had no constitutional power to permit slavery in the states and prohibit it in the territories, when, by the express language of the constitution, the territories had all the rights of the old states on their admission into the Union. He held with Jefferson and Madison, that as the Northern states had secured emancipation by the sale and diffusion of their slaves, it was unfair, under pretext of saving Missouri from its establishment, to darken the cloud over Virginia by confirming its existence there. The deepening of slavery in the old Southern states would make the laws concerning the slaves all the more rigorous, and abolition itself under such circumstances would still leave Virginia a "negro-ridden" community. On the other band, no argument was more absurd than the objection that the increase of the "slave states" could possibly keep pace with the progress of the North, constantly accelerated by the heavy emigration from Europe.

In 1821 Tyler declined a re-election to congress on account of impaired health, and returned to private life. But in 1823 he was again elected to the house of delegates of Virginia. The next year he was nominated to fill the vacancy created in the U. S. senate by the death of John Taylor, but his friend, Littleton Tazewell, a much older man in politics, was elected. In December, 1825, he was chosen by the legislature to the governorship of Virginia, and in the following year he was re-elected by a unauimous vote. He was elected to the United States Senate in 1827.

The strict-constructionists, such as Tyler, were finally forced into co-operation with the followers of Andrew Jackson — the majority of whom were members of the old Federal party. From the first Tyler's support of Jackson was coupled with the condition of Jackson's sustaining the Republican doctrines as maintained in Virginia.

Parties now assumed new names. The friends of Adams and Clay took that of National Republicans, while the friends of Jackson and Crawford assumed that of Democrats. But each party claimed to be the true representative of the old Republican party of Jefferson.

Tyler disapproved of nullification and condemned the course of South Carolina, as both "impolitic and unconstitutional." But he condemned the tariff measures of the administration for the same reasons, and for the additional one that they were the cause of the errors of South Carolina. Jackson's famous proclamation of Dec. 10, 1832, was denounced by him as " sweeping away all the barriers of the constitution," and as establishing in principle "a consolidated, military despotism." Under the influence of these feelings he undertook to play the part of mediator between Clay and Calhoun, and suggested to them the idea of the compromise tariff of 1833.

On the so-called " force bill," clothing the president with extraordinary powers for the purpose of enforcing the tariff, which had caused all the trouble, Tyler showed the courage of his convictions. The vote stood : yeas 32, nay one (John Tyler). The tendency of successive defections was to bring Tyler and his friends into closer and closer conditions with Clay and the National Republicans.

By 1836, he abandoned the Democratic Republican Party, resigning from the Senate and becoming at least a nominal Whig, though here again he disagreed with many of the party’s policies. By 1840, Clay had gone so far in conciliating Southern sentiment as to be considered the Southern candidate. The Northern representatives sought to defeat his election bv again putting up Gen. Harrison, to whom the South could not well object, as he was a Southerner, but who was preferable to Clay in the eyes of the manufacturers. They succeeded in defeating Clay, and Gen. Harrison became the candidate of the Whig party for the presidency. Tyler was the choice of everybody for the vice-presidency. The pair known as “Tippecanoe and Tyler too” shared a short time in office together.

It is idle to suppose there were not causes for the great enthusiasm manifested, apart from the clap-trap of politics. There was not a department of the government which was not in confusion, not an office which was not the seat of peculation, and not a principle of the constitution which had not been scorned and insulted by the course of the men in authority, under Jackson and Van Buren. A deep-seated conviction of the necessity of reform prevailed, and this conviction swept the Democrats from power.

The trinmph of the Whigs was followed by startling results. A collision between their varying factions was unavoidable. Clay hurried the quarrel. Without waiting for Harrison's inauguration, he at once assumed the dictatorship of the Whig party and revived the old National Republican measures which in his letters and public speeches he had declared "obsolete." Harrison caught pneumonia on Inauguration Day and died a month later.

Tyler was only 51, the youngest president ever up to that point. Tyler was also the first vice president to reach the presidency.

Tyler's views were even more fixed against the policy proposed than Harrison's. On 11 September 1841 all the cabinet, save Webster, resigned. The members were fully aware that according to the president's view all vacancies happening during the session had to be filled and sanctioned by the senate during the session.

During the next two years, while the Whigs controlled congress, Tyler received little support from that party, and the case was not changed much for the better when the Democrats, control led by the Van Buren wing of the party, succeeded to the seats which the Whigs had vacated. Tyler's reliance was on the wing of either party, known as the "states-rights" men in contradistinction to the Clay Whigs and Van Buren Democrats. After the resignation in 1841, he filled his cabinet with states-rights Whigs.

Although called “His Accidency” by his opponents, he refused to serve as acting president, insisting on all the powers of a duly elected chief executive. Because he opposed many of the policies of the party that nominated him, his administration was an intensely controversial one. He vetoed many bills enacted by the congressional majority and was the first president ever to have his veto overridden.

Tyler was ready to compromise on the banking question, but Clay would not budge. He would not accept Tyler's "exchequer system," and Tyler vetoed Clay's bill to establish a National Bank with branches in several states. A similar bank bill was passed by Congress. But again, on states' rights grounds, Tyler vetoed it. In retaliation, the Whigs expelled Tyler from their party. All the Cabinet resigned but Secretary of State Webster. A year later when Tyler vetoed a tariff bill, the first impeachment resolution against a President was introduced in the House of Representatives. They pushed through a resolution of censure in the House of Representatives and even denied him money to maintain the White House.

Tyler’s administration managed to accomplish a great deal in spite of its political difficulties. It settled a long-standing dispute over the boundary between the United States and Canada and signed the first commercial treaty with China. It reorganized the United States Navy, established the Weather Bureau, and ended the Seminole War.

. In 1842 he suggested to him, witli the concurrence of Lord Ashburton, the negotiation of a tripartite treaty by which to end the Texas war with Mexico, and to"add California and the West to the Union in return for the concession to Great Britain of the line of the Columbia river, as her boundary on the northwest, and the release to Mexico of the spoliation claims. He sent Fremont on his exploring expeditions to the West, despite the protest of Col. Abert and the higher grade officers of the engineer corps, thus enabling that competent officer to make known the passes of the Rocky Mountains.

Tyler’s last and probably most important achievement was to facilitate the annexation of Texas. At the very end of his term, Congress passed a resolution offering Texas the opportunity to join the Union. The final annexation of Texas was distinctly a crowning victory for President Tyler's policy.

In 1844, Tyler threw his support to James K. Polk, the Democratic nominee, and retired his plantation - “Sherwood Forest” because he considered himself a political outlaw — like Robin Hood.

Letitia Christian Tyler, the President's first wife, died in the White House in September 1842. A few months later, Tyler began courting 23-year-old Julia Gardiner, a beautiful and wealthy New Yorker. Their marriage in New York City on June 26, 1844, marked another first, the first president married while in office.

Tyler concentrated on managing his plantation and raising his second family in the 1850s. In 1860, hoping to avoid a civil war, he worked to find a compromise. He presided over the Washington Peace Convention of 1861, but when this failed, he voted for secession at the Virginia Secession Convention. Elected to the Confederate Congress, Tyler died on January 18, 1862, before it assembled.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|