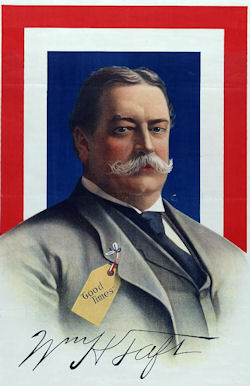

William Howard Taft (1909-1913)

President Taft’s single term in office was not a pleasant one. Progressive Republicans, including his mentor, Theodore Roosevelt, assailed him as too conservative; Old Guard Republicans saw him as too liberal. Defeated by Woodrow Wilson in 1912, Taft happily returned to practicing law. Although he lacked the charisma of Theodore Roosevelt, who had handpicked him for the office, President Taft scored many solid domestic gains. But, always more a jurist than a politician, in time he alienated his mentor and the "progressive" element in the Republican Party. This cost him reelection. Achieving a lifelong dream, he was later appointed as Chief Justice of the United States. In 1921, he achieved his life-long dream, when President Harding named him chief justice of the United States Supreme Court, the only President ever to sit on the Supreme Court. It was about this time that he remarked, “I don’t remember that I was ever president.”

President Taft’s single term in office was not a pleasant one. Progressive Republicans, including his mentor, Theodore Roosevelt, assailed him as too conservative; Old Guard Republicans saw him as too liberal. Defeated by Woodrow Wilson in 1912, Taft happily returned to practicing law. Although he lacked the charisma of Theodore Roosevelt, who had handpicked him for the office, President Taft scored many solid domestic gains. But, always more a jurist than a politician, in time he alienated his mentor and the "progressive" element in the Republican Party. This cost him reelection. Achieving a lifelong dream, he was later appointed as Chief Justice of the United States. In 1921, he achieved his life-long dream, when President Harding named him chief justice of the United States Supreme Court, the only President ever to sit on the Supreme Court. It was about this time that he remarked, “I don’t remember that I was ever president.”

Alphonso Taft, father of the future president, was already a prominent lawyer when he moved his growing family to fashionable Mount Auburn in 1851. The house he bought was a “beautiful, high, airy space,” with a view of the bustling city of Cincinnati and the Ohio River below. He quickly set about modernizing the ten-year old, two-story, Greek Revival, brick building, adding plumbing and a large addition in the rear. After the death of his first wife in 1852, he married Louise Torrey, who became stepmother to the two oldest Taft boys and bore four children of her own, including William Howard. The Taft household was a lively one, full of social activity and intellectual discussion ranging from Dickens to Darwin and from anti-slavery legislation to women’s suffrage. The children grew up with the family traditions of hard work, fair play, and public service. William Howard Taft lived at home until he left to study at Yale College in 1874; four years later, he graduated, second in his class.

Alphonso Taft’s tireless work for the Republican Party paid off in political appointments that took him and his family away from Cincinnati. They lived in Washington, DC between 1876 and 1877, while he served on President Grant’s Cabinet. In the 1880s, Alphonso Taft served as minister to Austria-Hungary and Russia. He rented out the Auburn Avenue house during these years, when his grown children were not there.

William Howard Taft began his studies of law at the Cincinnati Law School in 1878, passing the bar examination two years later. He practiced law in Cincinnati from late 1883 to 1887 and, like his father, became active in Republican politics. His first political appointment was as assistant county prosecutor in 1881. The following year, President Arthur named him district collector of internal revenue. Appointed to a vacancy on the Ohio Superior Court in 1887, Taft retained his seat the following year in the only election he ever ran in, except his election to the presidency ten years later. He held the judgeship until 1890.

Taft served in President Benjamin Harrison’s Justice Department in Washington, DC from 1890 to 1892; during this period, he also got to know Civil Service Commissioner Theodore Roosevelt. He returned to Cincinnati in 1892 as Federal circuit judge. President McKinley promised him the next appointment to the Supreme Court but in 1900 asked him to be chief civil administrator in the Philippines, which the United States acquired in the Spanish-American War. Sympathetic toward the Filipinos, he improved the economy, built roads and schools, and gave the people at least some participation in government. While Taft was in the Philippines, he reluctantly turned down an appointment as Supreme Court justice, because he felt that duty required him to complete the work he had begun in the Philippines.

President Theodore Roosevelt appointed Taft secretary of war early in 1904, though he also asked him to handle many special assignments. Again, an appointment to the Supreme Court arose and again Taft deferred to his current responsibilities. In 1908, his family and Roosevelt persuaded him to accept the Republican nomination for president. Taft disliked campaigning, but his conservative judicial style appealed to many voters, and he defeated William Jennings Bryan by more than a million votes.

As he had pledged during the election, Taft continued many progressive policies. During his single term, Taft initiated more antitrust suits than Roosevelt, and was also active in conservation. Taft obtained legislation removing millions of acres of Federal land from public sale; rescinded his predecessor's order to reserve certain lands as possible public dam sites, but ordered a study to determine what acreage should be protected; formed a Bureau of Mines in the Department of the Interior to safeguard mineral deposits; and supported a bond issue to undertake irrigation projects.

Furthermore, Taft backed extension of Interstate Commerce Commission power over the communications industry and in establishment of railroad rates; supported a modest tax on corporate earnings; advocated economy in Government; formed a commission to study Federal finances; signed campaign reform legislation; extended the Civil Service merit system; created the parcel post and postal savings systems; and oversaw creation of a Children's Bureau in the Department of Commerce and Labor. He also urged and saw passage of the 16th amendment to the Constitution, which authorized a Federal tax on personal income. Arizona and New Mexico, the last of the 48 contiguous States, were admitted to the Union during his administration.

Despite these accomplishments, Taft's legalistic concept of his office and his increasing reliance on Republican congressional leadership soon alienated reformers. He hoped for compromise to reduce tariffs, but defended the Payne-Aldrich Tariff (1909). This outraged progressives who sought rate reductions as a further challenge to the trusts. Taft was accused of being anticonservationist because he dismissed Forest Service chief Gifford Pinchot, a Roosevelt ally, after Pinchot had quarreled publicly on policy matters with him and Secretary of the Interior Richard A. Ballinger.

Taft's conduct of foreign affairs was also criticized. Included were his "dollar diplomacy" in the Far East and Latin America, U.S. inaction in the face of Japanese and Russian penetration in Manchuria, and American intervention to insure political and financial order in Nicaragua. Then, too, Taft suffered some stunning diplomatic setbacks. He pushed a tariff reciprocity treaty with Canada through Congress, but Canadians rejected the measure, at least partly because they feared annexation. With France and Great Britain, he negotiated agreements to arbitrate international disputes, but the Senate amended the treaties to such a degree that the embarrassed Taft rescinded them.

His support for the Payne-Aldrich Tariff, which kept tariffs on imports high, and his unwillingness to stretch his powers as president, alienated Roosevelt and the progressive wing of his own party, however. When Roosevelt chose to run against him as the candidate of the short-lived Progressive Party, this schism assured the election of Woodrow Wilson.

After he left office in 1913, Taft returned to Yale as a professor of law. In 1921, President Harding named him chief justice of the Supreme Court, which fulfilled his long-cherished ambition. Taft held that position until 1930 and died in Washington, DC a month after he retired.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|