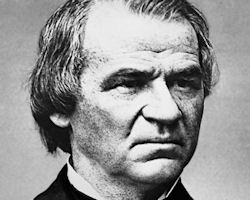

Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson, the 17th president of the United States, was a slaveholder who believed in Statesí rights, but was also a committed Unionist before the Civil War. He had no formal schooling, but through the sheer force of will became a self-educated man. In the early months of the Civil War, Johnson ó the only southern senator to remain loyal to the Union after his state seceded ó was obliged to flee that state to avoid arrest. When he succeeded to the presidency following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln in 1865, he tried to follow what Lincolnís policies would have been toward ďreconstructingĒ the defeated Confederacy. In doing so, he collided with the harsher policies advocated by the more radical Republicans in Congress. Impeached by the House of Representatives, he escaped removal from office by only one vote in the Senate.

Andrew Johnson, the 17th president of the United States, was a slaveholder who believed in Statesí rights, but was also a committed Unionist before the Civil War. He had no formal schooling, but through the sheer force of will became a self-educated man. In the early months of the Civil War, Johnson ó the only southern senator to remain loyal to the Union after his state seceded ó was obliged to flee that state to avoid arrest. When he succeeded to the presidency following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln in 1865, he tried to follow what Lincolnís policies would have been toward ďreconstructingĒ the defeated Confederacy. In doing so, he collided with the harsher policies advocated by the more radical Republicans in Congress. Impeached by the House of Representatives, he escaped removal from office by only one vote in the Senate.

Born in Raleigh, North Carolina, in 1808, Johnson grew up in poverty with no formal education. He arrived in Greeneville, Tennessee, in the fall of 1826 as an almost illiterate tailorís apprentice. He opened his own tailor shop there later that year. In 1827, he married Eliza McCardle. The future president studied diligently under his wife's tutelage and paid people to read to him while he worked. In about 1830, he moved his family to a two-story brick house at the corner of Water and Main Cross Streets. In 1830, he also relocated his thriving tailoring business to a small building that he bought and moved to a lot across the street from his home. The shop soon became a gathering place for political discussion and debate. By this time, Johnson had embarked on his political career.

Andrew Johnson may have lacked a formal education, but he possessed an innate talent for debate and oratory. His political career began when he was elected alderman of Greenville in 1829, and five years later he became the small town's mayor. In 1835 he joined the Tennessee state legislature, only to lose reelection two years later. He returned to state politics in 1839, moved to the state senate in 1841, and was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1843. By the 1840s, he owned a 350-acre farm outside of town, flour mills, and a number of town lots. After he won election to the United States House of Representatives in 1843, he sold the tailoring business but retained the property. Johnsonís humble beginnings and populist style endeared him to the working-class poor, but put him at odds with the wealthy landowners who controlled state politics. In 1853 his opponents gerrymandered him out of office. He retaliated by being elected governorótwice. By 1857 Johnson had gained enough support in the state legislature to be elected to the U.S. Senate.

He was a member of the United States House of Representatives from 1843 to 1853. A committed Jacksonian Democrat, he consistently favored the interests of the common man over those of the eastern aristocracy. While serving in the House, Johnson fathered the Homestead Act. This important piece of legislation, passed in 1862, opened public lands in the West to anyone who would farm 160 acres of land for five years.

As a senator, Johnson faced an agonizing decision when the southern States began to secede after the election of Abraham Lincoln in 1860. Although he owned slaves himself and believed in Statesí rights, he was also a strong Unionist. Immediately after President Lincolnís inauguration, Johnson desperately tried to persuade his home State not to secede. At great personal risk, he traveled back to Tennessee, narrowly escaping a lynch mob in Virginia. Tennessee seceded in June 1861.

Johnson was the only senator from the South who stayed in his seat, infuriating the South and making him a hero in the North. In 1862, after Union forces captured much of the State, President Lincoln appointed Johnson military governor of Tennessee. The National Union Party, the name the Republican Party assumed during the war, nominated Johnson as Lincolnís vice president in 1864. The party thought having Johnson on the ticket would appeal to other pro-war Democrats.

Johnson became president on April 15, 1865, following Lincolnís assassination. He entered office faced with the enormous challenge of ďreconstructingĒ the States of the former Confederacy. Johnson based his reconstruction programs on what he believed Lincoln would have done. His primary objective was to restore the Union by bringing the seceded States back as quickly as possible, on condition that they forswear secession and ratify the 13th Amendment to the Constitution, which abolished slavery. His policies also included pardoning all ex-Confederates who would take an oath of allegiance to the Union, except for former leaders and wealthy men, who could be pardoned only by the president.

Johnson opposed political rights for freedmen and called for a lenient reconstruction policy, including pardoning former Confederate leaders. The president looked for every opportunity to block action by the Radical Republicans. He had no interest in compromise. In 1866, Johnson vetoed the Civil Rights Bill, which provided citizenship to all men born in America, because he thought it was unconstitutional. Congress overrode his veto, the first time that happened to a piece of major legislation, and the House of Representatives made an unsuccessful attempt to impeach him.

When Johnson vetoed the Freedmen's Bureau bill in February of 1866, he broke the final ties with his Republican opponents in Congress. They responded with the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution, promising political rights to African Americans. In March of 1867 they also passed, over Johnsonís presidential veto, the Tenure of Office Act which was designed to limit the presidentís ability to shape his cabinet by requiring that not only appointments but also dismissals be approved by the Senate. Johnsonís stance placed him on a collision course with the radical Republicans who controlled Congress and were committed to punishing the South and securing full suffrage and legal equality for the freedmen.

By mid-1867, Johnsonís enemies in Congress were repeatedly promoting impeachment. The precipitant event that resulted in a third and successful impeachment action was the firing of Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, a Lincoln appointee and ally of the Radical Republicans in Congress. Stanton had strongly opposed Johnson's Reconstruction policies and the president hoped to replace him with Ulysses S. Grant, whom Johnson believed to be more in line with his own political thinking. In August of 1867, while Congress was in recess, Johnson suspended Stanton and appointed Grant as Secretary of War ad interim. When the Senate opposed Johnsonís actions and reinstated Stanton in the fall, Grant resigned, fearing punitive action and possible consequences for his own presidential ambitions. Furious with his congressional opponents, Johnson fired Stanton and informed Congress of this action, then named Major General Lorenzo Thomas, a long-time foe of Stanton, as interim secretary. Stanton promptly had Thomas arrested for illegally seizing his office.

This musical chair debacle amounted to a presidential challenge to the constitutionality of the Tenure of Office Act. In response, having again reinstated Stanton to office, Radical Republicans in the House of Representatives, backed by key allies in the Senate, pursued impeachment.

Led by an aging and ailing Thaddeus Stevens, the Joint Committee on Reconstruction rapidly drafted a resolution of impeachment, which passed the House on February 24, 1868, by a vote of 126 to 47. Immediately, the House proceeded to establish an impeachment committee, appoint managers, and draft articles of impeachment.

This impeachment trial was based on accusations that Johnson violated the Tenure of Office Act when he tried to dismiss Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. Johnson maintained that the recently passed legislation, specifically intended to limit his power as president, was unconstitutional. With Chief Justice Salmon Chase presiding, the trial began on March 5, 1868. The trial of the president, including testimony of 25 prosecution and 16 defense witnesses, became a public spectacle as well as a constitutional crisis. It gave the grand orators of the Senate a chance to dazzle the public with their speaking skills, and the trial was conducted mostly in open session before a packed gallery. The Senate trial acquitted him by one vote.

The turmoil over Reconstruction overshadowed the foreign policy successes of the Johnson administration. Chief among these was the purchase of Alaska from Russia for $7.2 million. Johnson did not gain the nomination for re-election in 1868 and returned to the homestead in Greeneville. Johnsonís wife managed to escape to join her husband during the Civil War, but the Confederates confiscated Johnsonís land, and the house suffered from being used as a hospital. When the family returned, they repaired the wartime damage to the house and remodeled it, adding a second-story to the ell and new furniture, wallpaper, and gifts received in Washington.

In January 1875, Tennessee elected Andrew Johnson to the Senate, the only former president ever to serve as a senator. His colleagues greeted him with applause. He served only briefly before he died in July, at the age of 66. His grave is on a hilltop site that is now at the center of the Andrew Johnson National Cemetery. Johnson selected the location for his grave for its peaceful feeling and restful views of the distant mountains. His body was wrapped in the American flag and his copy of the Constitution was buried with him. His wifeís grave is next to his.

In a 1926 case, the Supreme Court declared that the Tenure of Office Act had been invalid.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|