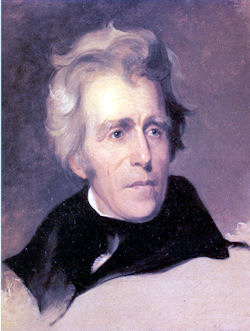

Andrew Jackson (1829-1837)

A charismatic, forceful leader, former Ways and Means member, Andrew Jackson came to office in 1829 as the people's President. Political clashes over the tariff and the Second Bank of the United States during his term prefigured the tumultuous years leading up to the Civil War. When Congress passed a bill to recharter the Second Bank of the United States, which Jackson charged with economic privilege, he vetoed it. As national politics polarized around Jackson and his opposition, two political parties began to evolve: the Democratic Republicans, or Democrats, and the National Republicans, or Whigs.

A charismatic, forceful leader, former Ways and Means member, Andrew Jackson came to office in 1829 as the people's President. Political clashes over the tariff and the Second Bank of the United States during his term prefigured the tumultuous years leading up to the Civil War. When Congress passed a bill to recharter the Second Bank of the United States, which Jackson charged with economic privilege, he vetoed it. As national politics polarized around Jackson and his opposition, two political parties began to evolve: the Democratic Republicans, or Democrats, and the National Republicans, or Whigs.

Seventh President of the United States. Born at Waxhaw Settlement, North Carolina, March 15, 1767. Died at the Hermitage, near Nashville, Tenn., June 8, 1845. Served in the Revolutionary Army at fourteen years of age. Studied law in Nashville, Tenn. Member of Congress from Tennessee 1796-97. United States Senator 1797-98. Justice of the Supreme Court of Tennessee 1798-1804. As General in the Army, he captured Pensacola from the English 1814. Defeated the English at New Orleans 1815. Governor of Florida Territory 1821. United States Senator from Tennessee 1823-25. Unsuccessful candidate for President 1824. Elected as Democratic candidate for President of the United States 1828, with John C Calhoun as Vice-President, and re-elected 1832, with M. Van Buren as Vice-President. Forced France to pay $5,000,000 for damages to U. S. Merchant Marine. Settled the difficulties in the secession of South Carolina over tariffs 1833. He was the first President who rose from the ranks of the common people. Established the U. S. Treasury Building and chose its present site. A fearless defender of the right and one of the most courageous Presidents elected by the people. Buried The Hermitage near Nashville, Tenn.

Frontier-born, Jackson was the first chief executive elected from west of the Allegheny Mountains, the first from other than Virginia or Massachusetts, and the first non-aristocrat. The charisma of “Old Hickory,” his renown as a military hero and Indian fighter, and his astuteness in politics assured his election as president.

Among all his rivals he was the only one conspicuous for not having a public career at Washington as member of Congress and cabinet officer. His great popularity in 1824 and the large vote he received were proof that he had been recognized as the sole representative of the hitherto silent, uninfluential but formidable democracy of the West. Up to 1824 not a single president had been nominated by even a representative vote of those who were later to elect him. The western section had been filling up with the descendants of those who had thus far controlled the government from east of the Alleghanies. Manhood suffrage was quite universally established in the new states and was winning its way rapidly eastward. Thus a great constituency was coming into existence both in the East and in the West that as yet had never exercised the predominance which the more daring and restless of its number felt was due them from the possession of an undoubted majority of voters. The critical moment came in 1824, when this democracy discovered the qualities for a candidate in the formidable personality of Andrew Jackson.

Although he was a wealthy, slave-holding planter and served in both Houses of Congress, he saw himself and both his supporters and opponents saw him as representing the common man. He not only expanded the powers of the office of president but also virtually redefined them.

Born in 1767 in the British colony of South Carolina, Andrew Jackson joined the American forces during the Revolutionary War. Captured by the British, he suffered great privations. After the Revolutionary War, he moved to Tennessee, where he became a lawyer and entered politics, becoming Tennessee’s first congressman, and later a senator and a judge on the Supreme Court of the State.

In 1804, Andrew Jackson purchased a 425-acre tract of land that he named The Hermitage. For the next 15 years, Jackson and his wife, Rachel, lived in a cluster of log buildings on the property. Here they entertained notable visitors including President James Monroe and Aaron Burr. Jackson led the life of a gentleman farmer at The Hermitage until 1813, when the Tennessee militia called him to active service. His military conduct during the Creek War brought him a commission as a major general in the regular United States Army. After the Battle of New Orleans in the War of 1812, he returned to The Hermitage a national hero.

In 1823, the Tennessee legislature elected Jackson to the United States Senate, but the following year he was an unsuccessful candidate for the presidency. Even though he won the greatest number of popular and electoral votes, he did not have a necessary majority in the Electoral College. This threw the election into the House of Representatives. The House selected John Quincy Adams as president in what Jackson considered a “corrupt bargain.” Jackson immediately resigned from the Senate to begin planning his next campaign. In the extraordinarily bitter campaign of 1828, he defeated Adams with a majority of 178 electoral votes to 83. His election was in many ways the first modern one, because by this time most States chose their electors by popular vote. His victory was clouded by the death of his wife. She died in January 1829, only a short time before he departed from The Hermitage for the inauguration.

The people's candidate had led by a vote quite astounding to those who had persisted in believing that Jackson's support would be a negligible quantity. In fact the aid given to Adams by Clay and the latter's appointment as secretary of state, the position generally understood at the time as leading directly to the presidency, seems to indicate conclusively that both these gentlemen regarded the Jackson vote as a passing ebullition of popular frenzy, as unaccountable as it was to be transitory.

By the time of Jackson's election, the Nation had come a long way since its founding, when its very survival had been at stake. It had not fully matured, but the patterns of thought and action that had begun to form during these critical years pointed to future trends and problems. Representative Government and democratic ideals would guide political development. The people would allow no hereditary or formal class distinctions. The United States would oppose European intervention in the affairs of the Western Hemisphere and avoid entanglement in European politics. Sectional rivalry would pose serious threats to national unity. The West would be a source of contention, as well as strength. Already it had become an article of the optimistic national faith that some would prosper and some would not. Likely as not, however, a man would be better off than his father, but not so well off as his son.

The most conspicuous feature of Jackson's presidency was his wholesale removals from office. Contemporary opinion seems to center upon this as the target for every shaft of ridicule and misrepresentation. Later historians appear to find it hard to be impartial on this point. By common consent the phrase, "the spoils system" has been allowed to stand as a valid criticism of Jackson's exercise of appointive power. It is difficult to justify so obvious a distortion of the plain facts of history.

His removals from office was not a party device to pay for votes nor a bribe for future support. Neither were these removals a mere revenge upon personal enemies for real or fancied attacks. Jackson honestly believed that ever since the establishment of the government, responsibility to the people had been sacrificed to secure efficiency in public office. It was his peculiar gift of political insight that enabled him to discover the popular demand for so radical a mesure of reform. Once in office as the people's choice, few presidents have more consistently and fearlessly carried into effect what was clearly the verdict of the majority. It was, however, far from a political millenium which he had been able to bring about. Public officials were still to be corrupt and incompetent for more than a generation.

Woodrow Wilson wrote "No doubt Andrew Jackson overstepped the bounds meant to be set to the authority of his office. It was certainly in direct contravention of the spirit of the Constitution that he should have refused to respect and execute decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States, and no serious student of our history can righteously condone what he did in such matters on the ground that his "intentions were upright'and his principles pure."

Jackson achieved three major political victories during his two terms as president. He closed the Second Bank of the United States. This action contributed to a nationwide depression and created difficulties during his successor’s term. In spite of threats of secession, he disallowed South Carolina to refuse to enforce Federal tariffs, thus “nullifying” a law with which they disagreed. In his third victory, Jackson, a famous Indian fighter, defied the Supreme Court and launched the removal of the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole Tribes from their homelands in the Southeast to Indian Territory in what is now Oklahoma. His successor completed the removal with the tragic Cherokee Trail of Tears.

"The hunger for Indian land was most intense in the Southern slave-owning states, and Jackson as a politician generally reflected Southern economic interests," Anthony Wallace writes in The Long, Bitter Trail: Andrew Jackson and the Indians. "Jacksonian Democracy … was about the extension of white supremacy across the North American continent," Howe writes in What Hath God Wrought, his history of the 1815 to 1848 period. "By his policy of Indian Removal, Jackson confirmed his support in the cotton states outside South Carolina and fixed the character of his political party."

Jackson wasn't alone; the entire Democratic party was in thrall to KIng Cotton, and receptive to policies like Native American removal that freed more land for cotton, and slavery. "The exaltation of the common man (meaning, on the frontier, the settler and speculator hungry for Indian land), the sense of America as the redeemer nation destined for continental expansion, the open acceptance of racism as a justification not only for the enslavement of blacks but also for the expulsion of Native Americans — these were popular, politically powerful themes that would have driven any Democratic President to press for a policy of Indian removal," Wallace writes.

In all reality, slavery was the source of Andrew Jackson’s wealth. The Hermitage was a 1,000 acre, self-sustaining plantation that relied completely on the labor of enslaved African American men, women and children. They performed the hard labor that produced The Hermitage’s cash crop, cotton. The more land Andrew Jackson accrued, the more slaves he procured to work it. Andrew Jackson purchased his first enslaved African American in 1794. Over the next 66 years, the Jackson family would own more than 300 men, women and children. The maximum they ever owned at any one time is about 150. At the time of his death in 1845, Jackson owned approximately 150 people who lived and worked on the property.

Andrew Jackson encouraged the slaves at The Hermitage to form family units, which was common for slave owners to do. Although the enslaved could not be legally married, the coupling of African American men and women in plantation “marriages” allowed for the creation of enslaved families. This was thought to discourage slaves from attempting escape, as it would be much more difficult for an entire family to safely flee from captivity.

In 1835 Jackson worked with his postmaster general to censor anti-slavery mailings from northern abolitionists. The historian Daniel Walker Howe writes that Jackson, "expressed his loathing for the abolitionists vehemently, both in public and in private."

Presidents from Washington to Jackson recognized that Western settlement was intimately related to the country's future wealth and power. And the people knew it, too. In 1783, 2 percent of them had lived west of the Alleghenies; by 1830 the figure was 28 percent. The Indians, the British, the Spanish—all retreated before the pioneer. Prosperous farms, plantations, and towns sprang up in the trans-Appalachian West, while soldiers, trappers, and traders explored and mapped the trans-Mississippi West. The settlement of the successive frontier zones from the Atlantic seaboard to the Pacific would become a major determinant in national growth.

Andrew Jackson died on June 8, 1845. His body lies next to that of his wife in the tomb at the southeast corner of The Hermitage garden.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|