Taras Bulba

Taras Bulba is the story of a Cossack, Taras Bulba, and his sons Ostap and Andrey. Andrey betrays the Cossacks for the love of a beautiful Polish woman and Taras kills him. A colorful and spectacular historical epic in the best of the then-dying old Hollywood tradition, the 1962 movie is probably the only exposure that the American public at large had to Ukrainian history, and in this alone it is a valuable work.

Taras Bulba is the story of a Cossack, Taras Bulba, and his sons Ostap and Andrey. Andrey betrays the Cossacks for the love of a beautiful Polish woman and Taras kills him. A colorful and spectacular historical epic in the best of the then-dying old Hollywood tradition, the 1962 movie is probably the only exposure that the American public at large had to Ukrainian history, and in this alone it is a valuable work.

The glorious novelist Nikolai Gogol (1809-52) was in fact Ukrainian by birth, but Russian by literary culture. Taras Bulba (1835), the greatest chivalric story of the 19th century, is an epic tale chronicling the lives of Cossack warriors. Taras Bulba, the short novel by Nikolai Gogol, has two versions. Tsarist Russian authorities condemned that version as being “too Ukrainian.” The later, official version was markedly more pro-Russian in nature.

The novel tells the story of an ageing [fictional] Cossack, Taras Bulba, and his two sons, the younger of which falls in love with a Polish woman. Eventually, that son is captured and shot by his own father. Gogol used the secondary or literary epic to portray the Russian national ideal embodied in the semi-historical mythic Cossack. The focus here falls on the portrayal of the Cossack martial ethos, sacralized brotherhood, and Russian spiritual vitality. The Zaporizhian Sich that Taras Bulba belongs to was later destroyed by the Russian Empress, Catherine II.

He and his fellow warriors assist their stronger Polish allies in defeating a band of Turkish invaders, only to have the Poles turn on the Cossacks and crush them. The Poles take over eastern Ukraine and force the Cossacks into hiding. Taras Bulba and his compatriots must cut off the scalplocks that mark them as Cossacks and take up peaceful occupations like farming.

Yankel, a Jewish merchant rescued by Taras from Cossack wrath against the Jews, is a stereotypical Jewish character of the period, by turns greedy, servile, and flattering. The Jew's scrawny physique, alien dress, and wild gesticulations were prime reasons why the Jew cannot be taken seriously, and why he cannot be presented problematically and existentially, even in death. Gogol’s Yankel in Taras Bulba escapes not only the fate of his fellow Jews drowned in the river by the Cossacks but also other near-fatal encounters. Gogol undoubtedly kept him alive because he needed a Jew to conduct Taras Bulba to Warsaw; he also was not about to sacrifice Yankel’s comic potential.

The portrayal of Jews in the most popular contemporary Russian novels, such as Faddey Bulgarin's Mazepa and Ivan Vyzhigin, both of which preceded Gogol's work, included more serious portrayals of both positive and negative Jewish types. Gogol quotes from Scott in reference to his own Jew, Yankel, the chapter compares Gogol's comic treatment of Yankel in Taras Bulba with the more problematic and existential treatment of Isaac of York and Rebecca in Ivanhoe. But somewhat unexpected is the appearance of an existentially serious Jew, a Jewess to be more exact, whom Gogol uses as a symbol of human suffering. Just as the comic Jew undermines the heroic text, the existential Jewess casts doubt on the exploitation of the comic Jew as a means of apophatically creating an epic hero.

At the time referred to in Taras Bulba - towards the middle of the seventeenth century — the position of the people had reached its worst. There were no Western Russians with even a shadow of their former freedom except the Zaporojian Cossacks. All the others had lost their lands; they had lost all authority over their own persons; and their last and most valued possession, their faith, was passing into obloquy and contempt with every increase of the power of Poland.

At the time referred to in Taras Bulba - towards the middle of the seventeenth century — the position of the people had reached its worst. There were no Western Russians with even a shadow of their former freedom except the Zaporojian Cossacks. All the others had lost their lands; they had lost all authority over their own persons; and their last and most valued possession, their faith, was passing into obloquy and contempt with every increase of the power of Poland.

Left to themselves the people might have risen in one place or another; but any action of that kind would have been stopped in blood. They could do nothing without organized power, and the Cossacks were the only organized power in Western Russia at that time. The Zaporojian Saitch therefore became the rallying point of every man who could leave home or kindred, and strike a blow for the Russian name and faith. The Cossacks therefore became defenders of the Church, liberators of the people, and national heroes.

So at the end of the sixteenth century began that long and bitter struggle — bitter almost beyond example even in that age of violencea struggle in which were involved interests far greater than those of the Cossacks or the people of Little Russia. In its ultimate significance it was a struggle not merely between Poland and a part of Russia, but between Poland and all Russia. Bound up with this was the struggle of Rome, straining every nerve to bring Eastern Christianity into submission to the Pope, and the struggle of Eastern Christianity, straining every nerve to preserve its independence.

The scene of Nikolai Gogol's “Taras Bulba," which has been pronounced the finest epic in the Russian language, is laid in Ukraine. It tells of the heroic deeds of the Cossacks, those war-lords who in the old days were the terror of the Turks and other neighboring nations, and whose blood flowed in Gogol's own veins.

Taras has two sons, who return from Kief University, and are taken by their father the very next day, despite their poor mother's pleadings, to the “Setch," or stronghold of the Zaporozhtzi (the Cossack soldiers). There is no war in prospect, and indeed the Cossacks have entered into arrangements whereby they have pledged themselves to peace; but no man is a man, according to Cossack standards, until he has been through active fighting, and forth with Taras, for the sake of his sons, stirs up his companions to go forth and attack their old enemies, the Poles.

Then follows a description of plunder and killing and siege. The younger son, Andreii, sees again a beautiful Polish girl whom he had met at Kief, and though sh is of the enemy, he falls madly in love with her, abjuring his father, brother, and country for her sake. Taras, maddened by his son's procedure, lures him in the thick of battle to the woods, and kills him. Ostap, the older son, is taken prisoner, and submitted to all sorts of tortures and indignities. Taras journeys several months later to Warsaw, where his son is to be executed. After that, Taras flings himself heart and soul into the leadership of the Cossacks against the Poles, and eventually meets his own death by being burned to death by the enemy.

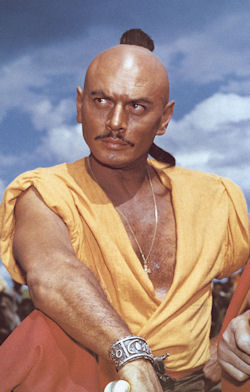

Taras Bulba is directed by J. Lee Thompson and adapted to the screen by Waldo Salt and Karl Tunberg from a story by Nikolai Gogol. It stars Yul Brynner, Tony Curtis, Christine Kaufmann and Perry Lopez. Out of United Artists, it's a DeLuxe/Eastman Color/Panavision production, with the music scored by Franz Waxman and cinematography by Joseph MacDonald. The writers allow the love story sub-plot between Andrei and Natalia to form the core of the plot. They were brought in after historical novelist Howard Fast (Spartacus) refused to tone down the screenplay. He wanted to include what was an important part of the Cossack/Pole war, that of the Cossacks anti-Semitic attack on Polish Jews.

The battles are fierce, violent and gripping, while the scenes in the Cossacks camps are joyous as men drink, sing, test their manhood by doing things like dangling over a bear pit, it's all very robust and entertainingly so. Yul Brynner wanted to capture the essence of Nikolay Gogol's novel in the film. By the time it reached the screen, it was dismissed as just another routine action picture in Cossack clothing--the very thing Brynner had hoped to avoid. The Cossack's "scalp-lock" is not on the back but the front.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|