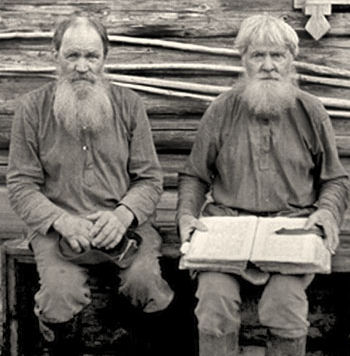

Old-Believers / Staroveri

Old Rite Russian Orthodox Church

The Old Believers [Raskolniki] were members of a religious movement, Old Ritualism, that arose in Russia in the mid-seventeenth century in opposition to Patriarch Nikon's reform of church rituals and texts. Nikon's reforms, introduced beginning in 1653, included the replacement of the double "hallelujah" with the triple "hallelujah," the use of three fingers instead of two in making the sign of the cross and amendments to Russian liturgical books in accordance with Greek models.

The Greeks had been famed for their heretical tendencies for centuries. One opportunity for the introduction of heresies was through the affiliation with the Greek church before the metropolitan of Moscow supplanted the patriarch of Constantinople in the beginning of the seventeenth century. After their expulsion the sacred books were revised and many of the absurdities introduced by ignorant copyists were expurgated. Those who rejected this revision were known as the Old Believers.

That the reaction against the reform was not more theological in character, but became a popular movement, and one vehemently hostile to the State Church, is explained by the peculiarly ritualistic bent of Orthodox Russian piety. The prevailing belief was that there was one original sacred text, which required only to be restored. This belief was associated with another, viz. that in the ritual there could be but one single 'true' form, which was likewise the original; this had been given by God, and any departure from it impaired its sacred and sanctifying power, and might even obstruct the divine activity conjoined with it.

Here the liturgy is not so much the expression and vehicle of divine wisdom-an aspect which is more prominent in the Greek Orthodox type of religion, and which to some extent mitigates the detrimental results of mere ceremonialism; in the Muscovite communion the liturgy, even in its minutest details, is a divine operation, a divinely revealed medium of intercourse with the sanctifying power of God.' Thus the Muscovites felt that Nikon's subversion of holy tradition in some sense maimed the activity of God, even as it debarred the faithful from access to Him. Again and again was heard the bitter outery that Nikon had brought perdition upon all the Russian saints who had been 'saved' by the older rites.

Old Believer - Patriarch Nikon

Old Believersfollow the older usages of the Orthodox faith, which were the same for all Russians before Patriarch Nikon's ecclesiastical reforms in the mid-seventeenth century. The believers who refused to accept the reforms or to renounce the old Orthodox rites and traditions set themselves in opposition to the official Church. This led to a schism. The Church of Old Believers ( staroobriatsy , starovery , raskol'niki ) has no counterpart in any other country. The Old Believers were severely persecuted, and they tended to resettle in remote areas in the North of European Russia, in the Volga region, and in Siberia.

Russia was evangelized from Byzantium, and for centuries, the Russian Church immigrant Greeks, governed by the Greek metropolitans of was entirely under the Byzantine influence-organized by Kiev, and subject to the ecumenical patriarch, who nominated these metropolitans. As was inevitable, the influence and predominance of the Greeks declined and at last passed away. Their position in the Church was irreconcilable in particular with the rise of a strong native State, which made Moscow its capital. The Church itself succeeded in making a close alliance with the national movement, and its complete emancipation.

On the death of Moscow Patriarch Josiph (15 April 1652), Nikon was appointed patriarch, and was consecrated on 25th July; his promotion was approved even by those among the Old Ritualists who became his bitterest enemies. Nikon exploits the theory of the third Rome by regarding the patriarch of Moscow as having been proclaimed the supreme hierarch of Christendom; and, if the tsar should become the recognized head of the world empire, what would be the position of the patriarch, the occupant of the sacred office from which were derived the jurisdiction, power, and authority of tsar and State alike.

In 1652 Patriarch Nikon (1605-1681), the head of the Orthodox Church supported by Tsar Alexi, introduced reforms to bring Russian Orthodox ritual and doctrine in line with those of the Greek Orthodox Church. The reforms were largely intended to bring Russian Orthodox liturgical practices in line with those of the Greek Orthodox Church. Perhaps the most visible involved the sign of benediction made by priests. Patriarch Nikon proposing that three fingers be used to represent the Trinity, while Russian Orthodox tradition preferred only two to represent the dual nature of Christ.

The Old Believer's reverence for the letter came from his belief that letter and spirit are indissolubly united, and that the forms of religion are as needful as its essence. Religion is to him, both as regards forms and dogmas, a whole, all whose parts hang together; and no human hand can touch this masterpiece of Providence without blemishing it. There is an occult sense in every word and in every rite. He cannot believe that any ceremony or formula of the Church is void of meaning or of efficacy. Looked at in this light, the Old Believer who marched to the stake for the sign of the cross, and sacrificed his tongue rather than chant another Hallelujah, grows highly respectable.

The Old Believers, rebelled against these reforms by insisting on keeping the older traditions of the Orthodox Church. A great part of the Russian society did not accept these reforms, which led to the schism (raskol) that created the Old Believers. During councils of Russian bishops in 1666-1667, opponents of the reforms were denounced as renegades (raskolnik) and persecuted mercilessly. At least 500 monks were murdered by Tsarist soldiers for their refusal to reform.

The resolution of the synod of 1667 greatly widened the cleavage between Church and Raskól by its enactment of excommunication and coercive measures against the latter. In the eyes of the Old Ritualists, the Church had now renounced God, and had become the woman drunken with the blood of the saints.' At first the State was regarded as less culpable; it had been seduced by the Church. But the latter attitude was soon abandoned in face of persecution. A decree of the regent Sófja in 1685 ordered the 'stiff-necked' sectarians, after three warnings, to be burnt, and those who did not denounce them to be knouted; those who recanted were set free if they found a sponsor. The cruel penalties inflicted by the patriarch Jakim (167490) fomented the fanaticism of the Old Ritualists to madness, and hundreds and even thousands, believing that the end of the world was imminent, sought death by burning or starvation. Some fled to the forests and desert places; others betook themselves to Poland, Sweden, Austria, Prussia, or even Turkey. Those who remained sought to form themselves into an organized community. This finally led to the formation of the separate community known as Old Believers.

The Old Believer was averse to giving in to the complicated mechanism of government. He would have nothing to do with the census, with passports or stamped paper. He strove to elude the new systems of taxation and conscription, and some of the Raskolniks were in a state of systematic revolt against the simplest of governmental methods. Religious grounds, of course, were found for this insubordination, and they had theological arguments to urge against the census, as well as against the registration of births and deaths. In the opinion of a strict Old Believer the right of numbering the people belongs to God alone, as is shown by the biblical record of David's punishment.

Old Believers use the Julian calendar and celebrate 38 holy days every year. Each holy day consists of extensive celebrations and special services, which make the Old Believers spend a significant amount of time in celebrations. They also celebrate mass every weekday and Sundays. There is a religious ceremony to mark every important event in an individual's life, and the events of everyday life also reflect religious beliefs: cooking and other household chores are blessed and there are rituals which must be performed upon entering someone's home. For weddings and funerals, ceremonies last a number of days and are quite elaborate. Traditionally, and even today, one of the key identifiers of Old Believers is their singing.

The Old Believers were considered heretics by the Orthodox church, but notwithstanding this their numbers grew, the innovations of Peter the Great giving no small impetus to the growth of the sect. In addition to this, the serfs found a refuge in the ranks of the Old Believers, and after their emancipation they clung to the old faith.

With the break of religious tradition in the middle of the seventeenth century the continuity of religious life in the official church was stopped. Two different ways might have been chosen. The one was that of the strict national tradition, so lately betrayed by the official church. The other was that of an entirely new movement deepening and enlarging the religious feeling and understanding. The former was in complete accordance with the past of the Russian church; the latter, in complete contradiction with it. The first was chosen by the so-called "Oldbelievers," or "Old-ritualists." The second was approved by the "sectarians."

One of the attractions which the Old-believers had for Russian peasantry was that they very often provided them with priests and with divine office in such places of Russia where there were no priests of the established church. Certain of the Old Believers drew near the Orthodox church and obtained the services of the Orthodox priests, but the vast majority of the sect remained consistently aloof from any such tendency. Other than the baptism, which the elders performed, they had no sacrament, and it was not possible for them to perform legally binding marriages. They considered the performance of military service, registration in a community, and prayer for the czar as of the devil.

Old Believer - Bezpopóvtsi vs Popóvtsi

The "Old-believers" were also divided into two opposite bodies, those " Acknowledging Priests," and the " Priestless," and their significance in the development of the Russian popular faith was far from equal. Both factions accused the official church of having betrayed the Orthodox religion. But the "Acknowledging Priests" thought that the true church still continued to exist in their own midst. The "Priestless" held to the extreme opinion that no church whatever existed, and that the second advent was on its way. This decisive view, however, was not adhered to at once even by this uncompromising party of the "Old-believers."

Some time after their excommunication at the council of 1667, the Schismatics were uncertain and wavered between these two views. According to the chances either of reconquering the former dominant position of the old creed, or of being obliged to surrender in the struggle with the established church, they alternately clung to the idea of the existence of a church or to that of the reign of Antichrist. But in measure, as the year's went on and the hope for a re-establishment diminished, they were brought to choose between these opposite views. Moreover, the choice became quite unavoidable, because they actually remained without priests and legal hierarchy.

At the moment when the "Old-believers" were proclaimed Schismatics by the established church, they had no bishops in their midst. Thus their priests could not be duly ordained, and accordingly they could not administer sacraments. Now, it was understood that a church without sacraments was no church at all; its further independent existence, therefore, became impossible. And, indeed, their theologians did not fail to find, contrary to the current doctrine, that Holy Writ itself foretold the extinction of the Christian church on the eve of the coming of Antichrist. In its turn, the extinction of the church served in their view to prove that the end of time was approaching. Therefore the extreme faction gave themselves up to wait for Antichrist, which made all further questioning about the future superfluous.

But the moderate faction, even though they believed in the coming of Antichrist, did not dare accept the bold theory of the complete extinction of the church. Had it not been promised by Christ himself, they objected, that the church should exist until the end of time? Of course, there were no bishops in their midst; but this only meant that Orthodox bishops must be supposed to exist somewhere else, say in the far East. The only task was then to find out where they were hidden. Meanwhile they acquiesced in acknowledging even such priests as came to the schism from the official church.

As none of the Russian bishops had joined the Raskól, a hierarchic order was impossible; and without that, again, a Church was impossible. Without an episcopate and a priesthood how could an excommunicated multitude become a Church? The priests of the old ordination' began to die out, and could not be replaced without bishops. The early leaders of the Raskól had tried to grapple with the difficulty, but without success. Avvakúm was disposed to recognize priests who had been ordained subsequently to the reform, but had renounced their errors, while Feódor, his companion in suffering (and eventually his fellow martyr), absolutely rejected the ordination of the State Church-certainly the more consistent view.

The struggle to find priests to lead illegal rites led to a split within the Old Believers. The question led at length to the division of the Old Ritualists into two large and mutually hostile groups, the Bezpopóvtsi (priestless') and the Popóvtsi ('priestly'). Bezpopóvtsi. gathered together in the district of Pomorje, in the government of Olónez-a region hitherto sparsely populated and almost churchless-solved the problem of the priesthood by reducing the number of the sacraments to two, baptism and confession, which could be dispensed by laymen, Mass, etc., being simply omitted. [the Roman Catholic Church adds five sacraments to baptism and the Lord’s Supper: penance, confirmation, marriage, holy orders (priestly ordination), and extreme unction (last rites)] In spite of all these things, the reforms of the priestless proved successful; the masses might have service. Their example was largely followed to become habituated to the changes.

Thus the moderate set of the "Old-believers" was brought to "acknowledge priests." This implied, however, an inconsistent supposition that some scraps at least of Orthodoxy were still lingering in the official church. But why then leave it at all? In fact, attempts at full reconciliation were more than once really made. Were it not for the uncompromising spirit of the established church, the reconciliation would have been attained long ago. Failing that, the "Old-believers" who "acknowledged priests" went on searching for bishops of their own. After a century of search, they succeeded in founding an independent hierarchy, whose first chief was an Orthodox bishop from the Balkans. He consented to be "corrected" regarding some details in the rite of his consecration according to the demands of the "Old-believers," and took his metropolitan seat at Bailaya Kreenitza, in Austria, close to the Russian frontier, in 1846. Then he ordained many Russian bishops, and the "Austrian hierarchy" flourished in Russia. Many "Old-believers," however, did not acknowledge the Austrian bishops, owing to some doubts about the "corrections" of the first metropolitan, and also because this great change too was an "innovation," not likely to please the illiterate conservative crowd who had grown accustomed to their "fugitive priests."

Richer by far was the religious life of the extreme set of the "Old-believers" - that of the "Priestless" people. Their beginnings were quite revolutionary. They prepared for the coming of Antichrist; hence they did not wish to acquiesce in any compromise. Antichrist was in their view Peter the Great. His personality, his reforms, his aversion to everything that was old, his persecution of schism, his way of treating religion, all served to prove that the Father of Lies was himself reigning in person. In consequence, there was no salvation for the people who should remain in the "world." Their device was, then, to flee from the world and, if possible, from life altogether.

Old Believer - Sects

The Popovtsy (‘priestly’), used ordained, but secretly dissenting, priests. The other group, the Bespopovtsy (‘priestless’), used lay-priests to lead their services. Eventually, both factions formed a number of smaller communities. The most important of these among the Bespopovtsy were the Pomortsy, Fedoseevtsy, and Filipovtsy.

The Old Believers were divided into many sects, one of the most noteworthy of which was that of the Deniers. The social dogma of the sect was in agreement with the most extreme anarchistic doctrines; the members led a vagabond existence and passed the greater portion of their time in prison. The method of life of the Deniers, their proneness to excesses, and their hatred of existing order made them close relatives to another mystic sect, the Beguny. The members of this cult avoided all obligations which were imposed by state, society, or family; they roam about, living only by begging. New members must burn all passports and papers which have reference to their social standing, for such documents are considered the work of the devil. The chief doctrine of the sect, to which every member must confess, is that anti-Christ stands at the head of the present church, state, and society; church services and sacraments only pollute faith; prayer should be in private without any ceremonial; marriage is a deadly sin and whoever wishes to live with a woman must do so without marriage, for the laws are not made for the righteous.

The Malakans consider the worshiping of images idolatry, they will take no oath, they keep Sunday holy, are obedient to the authorities, forbid cheating, stealing, violence, and lying. The Doukhobors believe in God, but not in the personality of Christ; for them there is only resurrection of the spirit, not of the body; they take no oath and consider marriage merely a contract which may be entered into and dissolved at will. As God's children they recognize only God over them; they rejected emperor and government, to whom they give only an unwilling obedience.

The members of another sect, the Christs, have discovered that every member is God and they call themselves the Sons of God. Divinity was concealed in every man, so read their fundamental tenet, and the chief ceremony was mutual adoration. There were many sects in Russia which considered suicide the only means of escaping sin and the devil, and in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries suicide epidemics occurred in which hundreds of persons perished. On the other hand, the Skobzens purified themselves through mutilations, and the Self-Burners, also an offshoot of the Old Believers, burned themselves alive.

Around the year 1770, a certain Euphimius rose up in protest against the compromises of the settlers in Moscow. He denounced city life as the modern Babylon and called the faithful to abandon landed property, which he considered to be the chief tie which held people down to settled life. The land was, is, and ought to be God's,” he declared, “man, should use it collectively, but never own it.” Under the slogan "Leave thy father and mother, take up thy cross, and follow me,” the disciples of Euphimius incited the faithful to flee from the towns and villages and take up a nomad life. They were called Beguny (Runners) or Straniki (Wanderers), and no doubt their preaching had much to do with the spread of communistic and anarchistic ideas among the Russian peasants. They were supposed to be celibates, but in case of "weakness of the flesh” they tolerated illicit relations which, they argued, are better than marriage, "for a married man gives himself up to evil forever."

Besides the radical "Wanderers," many other sects and groups formed within "The Old Believers” movement. Thus there were the “Gapers," who believed that God cannot deny to the faithful the flesh and blood of His Son. At their Holy Thursday Service they stood with their mouths wide open, expecting that angels would come and feed them with the Holy Sacrament for which their souls were hungry. The sect called “Molchalniki” (The Mutes) demanded vows of silence, but otherwise pursued a life similar to the “Wanderers” and probably was but a variety of them. Many of them were arrested, and in spite of the severest tortures they could not be forced to speak.

The “Nyemoliaki” (Nonprayers) were a mystical sect carrying the spirit of denial to its logical consequences. They rejected every outward form of worship and ritual and gave to scripture but an allegorical and rationalistic interpretation. They looked on everything as "spiritual” and believed they lived in the age of the Holy Ghost, where worship and understanding may be carried on only through the Spirit. Similar to the “Nonprayers” were the “Denyers,” who believed that since the reign of Antichrist commenced on earth all sacred things have been removed to heaven and therefore worship is possible only in direct communion with the Savior.

Old Believer - Social Development

Wherever they settled in the wilderness, they established villages of a more or less communistic type, and by hard work and cooperation quickly prospered. Their accomplishments as pioneers and colonizers were extraordinary, and to them principally was due the Russianizing of the great area of the North and of Siberia, which until then was populated only by widely scattered Finnish and Tartar tribes. Catherine II, who prided herself on her religious liberality, was lenient with them and permitted them to have their settlements even in Moscow. Wealthy "Old Believers” endowed cemeteries near Moscow, for they are very particular to bury their dead in a ground specially consecrated for this purpose, in conformity with their creed. Within the cemetery walls they built churches and around those sprung up settlements, to which the faithful Old Believers flocked, and which were the principal centers of their movement.

Facing persecution in their own country, many Russian Old Believers took advantage of the religious tolerance and relatively good conditions offered by landowners in the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (GDL). They emigrated to these countries at the end of the 17th century, when Poland and Lithuania were still referred to as the Commonwealth of the Two Nations.

Members of the Bespopovtsy settled mainly in Polish Livonia, Kurland, and the GDL. Most of these people belonged to the subgroup known as Fedoseevtsy. The subgroup had been founded in Russia’s Novgorod-Pskov area around the teachings of Feodosij Vasilyev but reached complete fruition in the Commonwealth.

Massive immigration from Russia solidified the Fedoseevtsy community in the GDL. The majority of immigrants came from the southern parts of the Russian province of Pskov. Others emigrated from the Tver and Novgorod provinces. Some immigrants came from the Smolensk, Galich, Suzdal, and Vorotynsk districts and from the cities of Moscow, Ustiug, and Serpuchov.

In the second half of the 18th century, immigration into the northwestern and western parts of the GDL intensified. This was due to sustained religious persecution in Russia and contrasting religious freedom and economic opportunity in the GDL.

Indeed, unlike in Russia, Old Believer practice in Poland and Lithuania was legalized quite early—allegedly in the late 17th century. By 1760, there were at least eight Old Believer parishes in the present territory of Lithuania. At the same time, the eschatological views of Old Believers were no longer of decisive importance.

Instead, their social status became more significant. In 1791, with a population of 100,000 to 180,000, Old Believers made up approximately 1%-2% of the Commonwealth of the Two Nations 8.79 million citizens. When Russian forces occupied the eastern parts of the Commonwealth of the Two Nations in 1792, many Old Believers moved further west. Between 1760 and 1795, nine more prayer houses were founded in the present territory of Lithuania. By the end of the 18th century, there were at least sixteen Old Believer parishes in all.

From 1679 to 1823, the Fedoseevtsy church organization was developed alongside the formation of the priestless Old Belief community in the GDL. One of the peculiarities of priestless Old Believers church life was the continuous participation of both laypeople and spiritual superiors (nastavniki) in the religious activities of the parish and the church organization, which was centered on autonomous parishes. As early as the end of the 17th century, the Fedoseevtsy movement saw the establishment of the “spiritual superior institute.” Another form of church administration during the early period of the Lithuanian Old Believer community was through councils.

Towards the end of the 19th century, Old Believers in Lithuania almost completely unified their religious views with the principles of the Pomortsy Community. They accepted all resolutions of a congress in Vilnius in 1906.

The Old Believers, who were puritanic in morals, became very prosperous and established many richly endowed monasteries, convents, schools, and orphanages. They had been particularly active since the beginning of the 20th century. And when after the 1905 revolution the old restrictions against their building churches, publishing literature, and openly agitating for their ideas were removed, they flourished greatly. The strength of "The Old Believers” was largely due to the fact that, unlike the State Church, their work was almost entirely carried on by the laity. Their priesthood existed only to administer the sacraments and render such services as the canons forbade to the laity.

The great wealth, particularly of the Moscow "Old Believers,” permitted them to give a good education to their children. In the beginning of this century there was a generation of young "Old Believers” who presented an unusual blend of ancient piety with modern liberal ideas and high cultural standards. Some of the noblest creations of Russian art, such as the Moscow Art Theater, were founded and financed by the cultured "Old Believers.” In politics and social reforms they united with the liberals and gave not a few able fighters to the revolution.

The 20th century saw continued tolerance of Old Believers, both in Lithuania and in Russia. On April 17 and October 17, 1905, an imperial decree was issued in the form of two manifestoes, one on religious tolerance and the other on freedom of conscience. The former law permitted for the first time the existence of Old Believer parishes in Russia, while the latter determined the order of their formation and the rights of their members and leaders. From that year until 1915, the Russian state recognized Old Believer parishes, as did the independent Lithuania between 1918 and 1940.

Given the Soviet Union’s well-known desire to maintain rigid control over every aspect of religious belief, the time after World War II was especially difficult and even tragic for the Old Believers. The Soviet authority began to interfere regularly and roughly with the church’s internal business. The church’s management was tested under strong pressure of the authorities and the secret police (the KGB). Like other religious and ethnic groups, the Old Believer Church had to search for other forms of acceptable expression within the context of the Communist state.

Following the Russian Orthodox Church’s acceptance of Old Believer rituals in the early 1970s and the dissolution of the Soviet Union, interest in the Old Believer faith grew slightly.

Old Believer - Today

Old Believer communities have historically been isolated, as those in Siberia or in Alaska. The communities are tight knit and members of the community look after each other. As of 2001 there were congregations in Belarus, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, and Russia, as well as in Oregon, Alaska and Pennsylvania in the United States.

It is difficult to estimate how many Old Believers exist. While the Europa World Factbook states that there were 278 groups registered in Russia in 2001, as estimated by the Patriarchate of the mainstream Orthodox Church, there are half a million Old Believers in Russia, and according to Father Romil Khrustalev, spokesman for the Old Believers, there are between 1.5 and four million Old Believers in Russia, Romania, and several former Soviet Republics. Sveta Graudt, writing for the Orthodox Christian News Service, reports that the number of Old Believers remaining is unclear, but it is known that there are far fewer than before the 1917 Revolution.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|