Tsonga

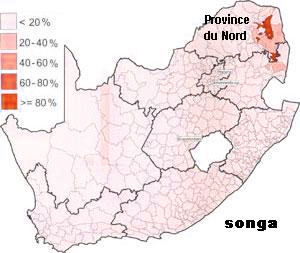

The Tsonga are a diverse population, generally including the Shangaan, Thonga, Tonga (unrelated to another nearby Tonga population to the north), and several smaller ethnic groups. Together they number about 1.5 million in South Africa in the mid-1990s, and at least 4.5 million in southern Mozambique and Zimbabwe.

The Tsonga are a diverse population, generally including the Shangaan, Thonga, Tonga (unrelated to another nearby Tonga population to the north), and several smaller ethnic groups. Together they number about 1.5 million in South Africa in the mid-1990s, and at least 4.5 million in southern Mozambique and Zimbabwe.

In the eighteenth century, the ancestors of the Tsonga lived in small, independent chiefdoms, sometimes numbering a few thousand people. Most Tsonga relied on fishing for subsistence, although goats, chickens, and crop cultivation were also important. Cattle were relatively rare in their economies, probably because their coastal lowland habitat was tsetse-fly infested. The Tsonga maintained a tradition of inheritance by brothers, in preference to sons, which is common in many Central African societies but not among other South Africans.

During the mfecane and ensuing upheaval of the nineteenth century, most Tsonga chiefdoms moved inland. Some successfully maintained their independence from the Zulu, while others were conquered by Zulu warriors even after they had fled. One Zulu military leader, Soshangane, established his command over a large Tsonga population in the northern Transvaal in the mid-nineteenth century and continued his conquests farther north. The descendants of some of the conquered populations are known as the Shangaan, or Tsonga-Shangaan. Some Tsonga-Shangaan trace their ancestry to the Zulu warriors who subjugated the armies in the region, while others claim descent from the conquered chiefdoms. The Tsonga and the Zulu languages remain separate and are mutually unintelligible in some areas.

Bantustan - Gazankulu

Gazankulu was the area between the Kruger National Park and the escarpment. Gazankulu was the homeland of the Shangaan and Tsonga people in South Africa. It was divided over two territories, west of the Kruger National Park, and its capital was at Giyani. It did not accept independence from South Africa, but was granted self-government in 1973. However, like the other nine homelands, the rest of the world did not accept it as a state.

Gazankulu was the area between the Kruger National Park and the escarpment. Gazankulu was the homeland of the Shangaan and Tsonga people in South Africa. It was divided over two territories, west of the Kruger National Park, and its capital was at Giyani. It did not accept independence from South Africa, but was granted self-government in 1973. However, like the other nine homelands, the rest of the world did not accept it as a state.

The Tsonga-Shangaan homeland, Gazankulu, was carved out of northern Transvaal Province during the 1960s and was granted self-governing status in 1973. The homeland economy depended largely on gold and on a small manufacturing sector. Only an estimated 500,000 people--less than half the Tsonga-Shangaan population of South Africa--ever lived there, however. Many others joined the throngs of township residents around urban centers, especially Johannesburg and Pretoria.

In the 1980s, the government of Gazankulu, led by Chief Minister Hudson Nsanwisi, established a 68-member legislative assembly, made up mostly of traditional chiefs. The chiefs opposed homeland independence but favored a federal arrangement with South Africa; they also opposed sanctions against South Africa on the grounds that the homeland economy would suffer. In areas of Gazankulu bordering the seSotho-speaking homeland of Lebowa, residents of the two poverty-stricken homelands clashed frequently over political and economic issues. These clashes were cited by South African officials as examples of the ethnic conflicts they claimed would engulf South Africa if apartheid ended.

Gazankulu was one of the smaller homelands in South Africa, and covered an area oj about 675,000 ha mainly in the north-east Lowveld the Transvaal. Gazankulu territory connsisted of four separate units: the region notrth of the Letaba River (the largest unit) which borders on the Kruger National Park, the central unit in the vicinity of Tzaneen and the onc situated farter east between Bushbuckridge and the Kruger National Park. The fourth unit, near Phalaborwa, was of recent origin (as part of consolidation), and was the Lulekani District of the Majeje Tribe.

The name Gazankulu is derived from Lake Gaza and Gazaland in nearby Mozambique. The Shangaan people living in the area are closely related to the Tsonga who live in Mozambique. Originally Gazankulu was named Machangana, for its Shangaan inhabitants. Gazankulu was granted internal self-government on 01 February 1973.

In part because Gazankulu, the homeland assigned to the Tsonga, is so small and in part because the ancestors of many South African Tsonga lived nowhere near Gazankulu but settled instead among several other peoples, less than half of all the Tsonga live in the homeland. Moreover their long history of fragmentation and the differential adaptation of various sections of them to other peoples and to urban life suggest that they are less likely than other groups to conform to the model of a people called for by the government's doctrine.

Hudson William Edison Ntsan’wisi studied Linguistics at Georgetown University in Washington DC and at Hartford Seminary also in the US. In light of his leadership qualities, first as a teacher and later an inspector, Ntsan’wisi was elected the first Chief Minister of the Tsonga-Machangana Legislative Assembly, later known as Gazankulu in 1969. He served as Chief Minister of Gazankulu (one of the 8 homelands) for 24 years, until his death on 23 March 1993.

On 01 February 1973 the republic of South Africa granted independence to Venda and Gazankulu. This move was in line with the government's internal control strategy of 'divide and rule'. These Bantustans were never given international recognition by the international community. However, states like Israel and Taiwan gave them some measure of acknowledgment, falling short of full diplomatic recognition.

Several of the homeland leaders, notably chief ministers such as Cedric Phatidi of Lebowa, Buthelezi of KwaZulu, Hudson Ntsanwisi of Gazankulu, and Kenneth Mopeli of QwaQwa, rejected "in- dependence" for their fragmented territories because acceptance would mean continued economic subservience to South Africa.

From space, the Gazankulu Homeland, one of the several black African homelands, contains dozens of small white patches marking “rural ghettoes”, population centers where hundreds of thousands of black Africans were forced to set up their homes during the height of the apartheid regime of the past South African government. The patches are evidence of denudation of the natural vegetation due to overpopulation and overgrazing by herd animals. Shuttle imagery shows not a single patch in this area in 1983, indicating the scale and speed of the population removals which resulted in the ghettoes.

Since 1994, the former homeland of Gazankulu has formed part of the Limpopo Province.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|