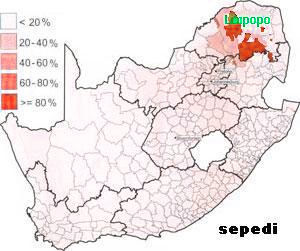

Northern Sotho / Sepedi

The heterogeneous Northern Sotho are often referred to as the Pedi (or BaPedi), because the Pedi make up the largest of their constituent groups. Their language is sePedi (also called seSotho sa Leboa or Northern Sotho). This society arose in the northern Transvaal, according to historians, as a confederation of small chiefdoms some time before the seventeenth century. A succession of strong Pedi chiefs claimed power over smaller chiefdoms and were able to dominate important trade routes between the interior plateau and the Indian Ocean coast for several generations. For this reason, some historians have credited the Pedi with the first monarchy in the region, although their reign was marked by population upheaval and occasional military defeat.

The heterogeneous Northern Sotho are often referred to as the Pedi (or BaPedi), because the Pedi make up the largest of their constituent groups. Their language is sePedi (also called seSotho sa Leboa or Northern Sotho). This society arose in the northern Transvaal, according to historians, as a confederation of small chiefdoms some time before the seventeenth century. A succession of strong Pedi chiefs claimed power over smaller chiefdoms and were able to dominate important trade routes between the interior plateau and the Indian Ocean coast for several generations. For this reason, some historians have credited the Pedi with the first monarchy in the region, although their reign was marked by population upheaval and occasional military defeat.

During the nineteenth century, Pedi armies were defeated by the Natal armies of Mzilikazi and were revived under the command of a Pedi chief, Sekwati. Afrikaner Voortrekkers in the Transvaal acquired some Pedi lands peacefully, but later clashed with them over further land claims. By the 1870s, the Voortrekker armies were sufficiently weakened from these clashes that they agreed to a confederation with the British colonies of Natal and the Cape that would eventually lead to the South African War in 1899.

The smaller Lobedu population makes up another subgroup among the Northern Sotho. The Lobedu are closely related to the Shona population, the largest ethnic group in Zimbabwe, but the Lobedu are classified among the Sotho primarily because of linguistic similarities. The Lobedu were studied extensively by the early twentieth-century anthropologist J.D. Krige, who described the unique magical powers attributed to a Lobedu female authority figure, known to outsiders as the rain queen.

Bantustan - Lebowa

Lebowa was a Bantustan situated in the Northern Transvaal Region of the Republic of South Africa. Prior to the construction of the Bantustans, the area was very ethnically heterogeneous, populated by a range of chieftainships, including that of the people that came to be known as ‘Shangaan’ and Pulana, many of whom were intermarried and did not have strong ethnic identities. It was only with attempts by the apartheid government and the effort to concretely ‘retribalise’ that the area configured more strictly along ethnic lines, often producing an aggressive nationalism.

Lebowa was a Bantustan situated in the Northern Transvaal Region of the Republic of South Africa. Prior to the construction of the Bantustans, the area was very ethnically heterogeneous, populated by a range of chieftainships, including that of the people that came to be known as ‘Shangaan’ and Pulana, many of whom were intermarried and did not have strong ethnic identities. It was only with attempts by the apartheid government and the effort to concretely ‘retribalise’ that the area configured more strictly along ethnic lines, often producing an aggressive nationalism.

The Northern Sotho homeland of Lebowa was declared a "self-governing" (not independent) territory in 1972, with a population of almost 2 million. Economic problems plagued the poverty-stricken homeland, however, and the population was not unified by strong ethnic solidarity. Lebowa's chief minister, Cedric Phatudi, struggled to maintain control over the increasingly disgruntled homeland population during the early 1980s; his death in 1985 opened new factional splits and occasioned calls for a new homeland government. Homeland politics were complicated by the demands of several ethnic minorities within Lebowa to have their land transferred to the jurisdiction of another homeland. At the same time, government efforts to consolidate homeland territory forced the transfer of several small tracts of land into Lebowa.

The 1971 Bantu Homelands Constitution Act that made Lebowa a full-fledged, self governing territory. The Legislative Assembly consisting of 60 Magosi (chiefs) and 40 commoners was formed with M.M.Matlala as the first Chief Minister. Lebowa was therefore an institution of Magosi who were selected by Pretoria and roped in to implement the policy of separate development. Kgosi Mokgome Maserumula Matlala, the Chief Councillor of Lebowa from 1969 to 1972 and Chief Minister for a year ending in 1973 named his party the Lebowa "National Party.?

Bantustan power rested with a hierarchy of Magosi from tribal to territorial levels, who were made utterly dependent on the patronage of the Department of Native Affairs. Magosi became more accountable to the Department than to their subjects, thus eroding their legitimacy.

Lebowa never gained any recognition by the International community and was, together with other nine Bantustans, unpopular and mostly despised by blacks and vehemently opposed by the major black nationalist organisations. The grant of "independence" to Transkei on October 26, 1976 was not followed by KwaZulu, Lebowa, Gazan-kulu, and the other smaller units which resisted prodding by the Pretoria government to follow Transkei's lead, fearing the independence would be meaningless in view of their heavily fragmented territories (Lebowa was divided into thirteen units and KwaZulu into forty-four in 1975), the fragility of their economies, and their lack of revenue sources. The possible loss of South African citizenship and residence rights made the issue of independent homelands especially objectionable to Blacks living and working in urban South Africa.

A striking feature of the platinum mining industry under late apartheid was that the bulk of its mineral reserves fell within the borders of two of the nominally independent homeland territories into which the black majority had been racially segre- gated and ethnically divided. Bophuthatswana encompassed a substantial swathe of the western Bushveld while the lion’s share of both the northern and eastern limbs of the BIC rose within Lebowa.

On form of black minerals ownership was unique to Lebowa, and may be termed ‘mineral trust property’. In 1987, the mineral rights in the former SADT land held by the Lebowa government were separated and transferred wholesale to a new structure – the Lebowa Minerals Trust (LMT) – in terms of the Lebowa Minerals Trust Act (No. 9 of 1987). The LMT was explicitly defined as a corporate body possessing mineral property in a similar manner to a private rights holder, as opposed to mineral rights held by the state. This endowed the LMT with absolute authority to grant mineral rights to third parties to prospect and mine, and to receive the entire revenue.

The LMT was a particularly transparent instrument of appropriation for the (notoriously corrupt) Bantustan elite. In 2000, the LMT was reported to control 1500 title deeds to mineral rich farms, of which 1432 were registered in the trust’s name. The total value of these assets were estimated to be in the region of R280–R300 million, while the LMT’s royalty income was close to R20 million a year. The LMT was also a means of ensuring that the ‘barrier’ of landed property was distinctly porous on the eastern Bushveld. By 1994, Anglo American’s Rustenburg Platinum Holdings (RPH) had gained exclusive control of the mining rights to 26 farms through a series of agreements with the Lebowa government, which resulted in the formation of several joint-venture companies. As mining rights were perpetual rights in law, this effectively enabled RPH to monopolise the entire eastern limb of the Bushveld Igneous Complex (BIC).

Lonmin is listed on the stock exchanges in London and Johannesburg. The Company engages in the discovery, extraction, refining and marketing of platinum group metals (PGMs) and is one of the world's largest primary producers of PGMs. Lonmin established mining operations are located on the western limb of the Bushveld Igneous Complex (BIC) in South Africa. The BIC, which hosts almost 80% of the world’s PGM resources, extends approximately 350 kilometers east to west and approximately 250 kilometres north to south.

By 1994, and after the publication of a damning report on corruption and mal-administration in Lebowa’s Department of Education, it looked like students of schools in what then (primarily) became the Northern Province, would, in fact, be left to “inherit the wind.” Such levels of corruption have been taken as almost paradigmatic of the rotten core of the Bantustans.

The Public Affairs Research Institute [PARI] of Johannesburg wrote in 2014 that "The Bantustans and their borders however, are a lot closer to contemporary reality than the map suggests. The legacy of the vast administrations, ethnic enclaves and traditional authority politics are very much present in contemporary South Africa. One only has to look at the functioning of some of the worst performing provinces to see how the legacy of the Bantustans play out in the day-to-day lives of large sections of the South African population. Take Limpopo (former Venda, Gazankulu and Lebowa), Mpumalanga (former KaNgwane, Gazankulu and KwaNdebele) and Eastern Cape (former Ciskei and Transkei), where each one of these provincial administrations have been cobbled together out of the multiple departments, agencies and tribal authorities making up the respective former homelands. The Department of Education in the former Lebowa, for example, had huge administrative gaps allowing for corruption through mismanagement of receipting and stocktaking systems. "

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|