Mpumalanga

Mpumalanga means “Place Where the Sun Rises”. The province’s spectacular scenic beauty and abundance of wildlife make it one of South Africa’s major tourist destinations. With a surface area of only 79 490 km2, it is the second-smallest province after Gauteng, yet has the fourth-largest economy in South Africa. Bordered by Mozambique and Swaziland in the east, and Gauteng in the west, it is situated mainly on the high plateau grasslands of the Middleveld, which roll eastwards for hundreds of kilometres. In the north-east, it rises towards mountain peaks and terminates in an immense escarpment. In some places, this escarpment plunges hundreds of metres down to the low-lying area known as the Lowveld.

Mpumalanga means “Place Where the Sun Rises”. The province’s spectacular scenic beauty and abundance of wildlife make it one of South Africa’s major tourist destinations. With a surface area of only 79 490 km2, it is the second-smallest province after Gauteng, yet has the fourth-largest economy in South Africa. Bordered by Mozambique and Swaziland in the east, and Gauteng in the west, it is situated mainly on the high plateau grasslands of the Middleveld, which roll eastwards for hundreds of kilometres. In the north-east, it rises towards mountain peaks and terminates in an immense escarpment. In some places, this escarpment plunges hundreds of metres down to the low-lying area known as the Lowveld.

The area has a network of excellent roads and railway connections, making it highly accessible. Because of its popularity as a tourist destination, Mpumalanga is also served by a number of small airports, including the Kruger Mpumalanga International Airport.

Mbombela (previously Nelspruit) is the capital of the province and the administrative and business centre of the Lowveld. Other important towns are eMalahleni (previously Witbank), Standerton, Piet Retief, Malelane, Ermelo, Barberton and Sabie.

Mpumalanga lies mainly within the Grassland Biome. The escarpment and the Lowveld form a transitional zone between this grassland area and the Savanna Biome. The Maputo Corridor, which links the province with Gauteng, and Maputo in Mozambique, generates economic development and growth for the region.

The people

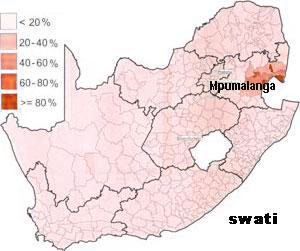

Mpumalanga is home to just over 3,6 million people, according to Stats SA’s Mid-year Population Estimates, 2011. The principal languages are siSwati and isiZulu. Mpumalanga today is made up of a truly diverse mix of nations, the product of a pioneering history that attracted armies, adventurers and travellers from all corners of the world. They came to farm the land, to prospect for minerals, to hunt big game, or as businessmen to trade and prosper from the many economic opportunities that arose as the region developed. Others arrived from Europe to lay the railway from Maputo to Pretoria.

Mpumalanga is home to just over 3,6 million people, according to Stats SA’s Mid-year Population Estimates, 2011. The principal languages are siSwati and isiZulu. Mpumalanga today is made up of a truly diverse mix of nations, the product of a pioneering history that attracted armies, adventurers and travellers from all corners of the world. They came to farm the land, to prospect for minerals, to hunt big game, or as businessmen to trade and prosper from the many economic opportunities that arose as the region developed. Others arrived from Europe to lay the railway from Maputo to Pretoria.

The Swazi people can trace their origins to a region in Kenya on the slopes of Mount Kenya, some 140km north of Nairobi. They arrived in Southern Africa under their chief, Dlamini, and settled initially near Maputo. The tribe then moved southwards to the Pongola River and later still into present day Swaziland where it developed its Swazi identity under King Sobhuza I (1815-1836) and later his son, King Mswati II. The latter was credited with uniting the many clans into one nation. Mswati II also set out to enlarge his empire by attacking his northern neighbours to as far north as Venda and the Limpopo River. King Mswati was a cruel and determined leader, whose army was greatly feared. However, in one engagement, his army attacked the Pulana clan in the valleys of the Blyde River Canyon. The Pulana succeeded in defeating the Swazis by hurling rocks down on them from the cliffs above. The survivors of this battle, fearing reprisals if they returned to their king, settled to the north of Swaziland in small pockets, where the same families live to this day.

The Ndebele people of north west Mpumalanga now live in the area around Dennilton where, after a century of struggle, they were granted land on which to re-establish their people, who had been scattered throughout South Africa by war and restrictive legislation. The history of these people has been one of hardship and turmoil as successive waves of foreigners invaded their historic homeland. The Ndebele are a Nguni people. During the third and fourth centuries they migrated to the Zebedelia and Pretoria areas in a series of migrations, and it was in this region that they established their tribal lands during the mid-17th century. Today a bronze sculpture of the Ndebele leader Nyabela stands outside the Mapoch Caves, to remind the descendants of this brave and proud people of their turbulent past.

Manukosi Shoshangane Nxumalo, a fighting general in Zwide's Ndwandwe army, was defeated by Shaka's army in Zululand and driven north of the Inkomati River, where he established a new kingdom in the Gaza Province of Mozambique. Over the years his empire grew through alliances with local chiefs and through war, until it extended to as far north as the Zambezi River. When Shoshangane died in 1856 he was succeeded by one of his two sons, Mawewe. The new king, in turn, fell victim to inter-family fighting and was deposed by his brother Mzila. Years of fighting throughout the region then weakened the Shangane empire, and in the absence of strong leadership the clans scattered through a wide area of Mpumalanga, the Northern Province and Mozambique. Today the Shangane nation is once again well defined stretching from south of Bushbuckridge into the Northern Province, and eastwards into Mozambique.

The Pedi, who occupy the land across the northern border of Mpumalanga in the Northern Province, have had a strong influence on the history and development of the Mpumalanga through the years. Many of their leaders have contributed meaningfully to the development of the province, and are set to continue to do so in the new South Africa. the europeans and asians

Agriculture and forestry

Mpumalanga is a summer-rainfall area divided by the escarpment into the Highveld region with cold frosty winters and the Lowveld region with mild winters and a subtropical climate. The escarpment area sometimes experiences snow on high ground. Thick mist is common during the hot, humid summers. An abundance of citrus fruit and many other subtropical fruit – mangoes, avocados, litchis, bananas, papayas, granadillas, guavas – as well as nuts and a variety of vegetables are produced here.

Mbombela is the second-largest citrus-producing area in South Africa and is responsible for one third of the country’s export in oranges. The Institute for Tropical and Subtropical Crops is situated in Mbombela. Groblersdal is an important irrigation area, which yields a wide variety of products such as citrus fruit, cotton, tobacco, wheat and vegetables. Carolina-Bethal-Ermelo is mainly a sheepfarming area, but potatoes, sunflowers, maize and peanuts are also produced in this region.

Industry and manufacturing

Most of the manufacturing production in Mpumalanga occurs in the southern Highveld region; especially in Highveld Ridge, where large petrochemical plants such as Sasol II and III are located. Large-scale manufacturing occurs especially in the northern Highveld area, in particular chromealloy and steel manufacturing. In the Lowveld subregion, industries concentrate on manufacturing products from agricultural and raw forestry material. The growth in demand for goods and services for export via Maputo will stimulate manufacturing in the province.

Mpumalanga is rich in coal reserves. The country’s major power stations, including the three largest power plants in the southern hemisphere, are situated in this province. One of the country’s largest paper mills is situated at Ngodwana, close to its timber source. Middelburg produces steel and vanadium, while eMalahleni is the biggest coal producer in Africa.

History

The communities that fall within the boundaries of the province of Mpumalanga have a history with a depth, vividness and significance, which cannot easily be matched by other regions of South Africa. It has major archaeological sites giving evidence of human habitation stretching back more than 50 000 years and illuminating both stone age and iron age society. The abundant rock art found all over the province is our dynamic heritage that points to the San (hunter-gatherers) as the oldest occupants of the area. There is a diverse array of rock art sites belonging to hunter-gather, herder and farmer communities.

It was a vital zone of settlement and interaction for a wide range of societies and played a critical role in the emergence of powerful African states. Throughout the Mpumalanga hills and mountains exist hundreds of examples of San (bushman) art. This art serves as a window looking into the lives of the San hunters and gatherers who inhabited the area centuries before the arrival of the Nguni people from the north.

The region abounded with all types of game, plants, birds and insects. The rivers ran full, providing for the needs of these early inhabitants. Later came the first of the Nguni people who arrived with herds of cattle, and mined red ochre in the hills south of Malelane. Early smelters, which pre-date the main Nguni influx, have been excavated, indicating that the use of iron and copper was well advanced during these years. Similarly, early pottery fragments and sculptural artifacts unearthed in the hills on the Long Tom Pass, notably the "Lydenburg heads" have been described as a major art find.

Around 1400 AD the second Nguni migration arrived from the north with their vast herds of cattle. These people had advanced the art of iron smelting, and built stone-walled houses for their settlements. The creation of the Swazi nation as we know it today commenced at the time of King Ngwane. The area, which was then demarcated by tribal boundaries, was referred to as KaNgwane, a name that still stands. Clans forged friendships with other clans through marriage and for safety of numbers, while frequent raids against neighbouring clans served to replenish cattle herds and to extend tribal lands.

The movements of tribal chiefs through the region had a profound effect on the formation and bonding of nations. Most notable was the influence of Zulu king Shaka, whose empire stretched southwards from the Swaziland border to the Tugela River. Shoshangane, who escaped from Zululand and settled in the Gaza Province of Mozambique, was the founder of the Shangane people, while Mzilikazi, after being forced to flee Zululand to escape the wrath of Shaka, travelled through the region on his way north to establish an empire in southern Zimbabwe. His passage was marked by death and destruction as he sought to subjugate the Ndebele people.

For centuries, Mpumalanga was populated by warrior clans who roamed the hills and plains in search of grazing for their cattle and safety for their people. Theirs was a life of war and survival as the centers of power moved from one clan to another. The oral tradition passed down in the folklore of the people is today an important record of the lives and tribal history of the inhabitants.

With the arrival of Trekkers in the 1840s it became one of the most dramatic and hard fought frontiers in 19th century South Africa. It was an important theatre of the South African War and crucible of white politics. In the 20th century, it became a major centre of economic development, and of the evolution of conservationist policy and practice. It was also an important arena of resistance and armed insurgence.

The province’s rich archaeological heritage has been a subject of research and intellectual inquiry among eminent scientists in the world. The evidence of stone-walled settlements bears testimony to the existence of human settlements and their predecessors. These are human settlements of societies that existed during the early Iron Age development stage of human societies. The world renowned “The Lydenburg heads” are part of the archaeological treasure trove that presents evidence of early civilisation pre-dating colonial settlements. Many will agree that this archealogical evidence deconstructs the ideological inscriptions in dominant colonial discourses that civilization was brought about by the existence of colonial settlers. The excavated trade goods offer insights into the dynamic existence of a dynamic industry in iron, tin, copper, bronze, and ochre. The existence of marine beads and marine shells point to the evidence of thriving trade networks that linked regional patterns of trade to the coast, suggesting that Mpumalanga had been an important trading channel for many years.

The history of Mpumalanga represents the history of South Africa in microcosm with elements of the conflicts, compromises, tragedies and triumphs that shaped the emergence of the new South Africa. But little of this is apparent to the readers of conventional popular histories and tourist literature or to those that log on to the innumerable websites or visit recognised heritage sites. These sites and sources continue to be informed by a racially skewed, regionally fragmented, unimaginative and truncated representation of the past. They fail to comprehend or to convey the fact that Mpumalanga has been from time immemorial a zone of interaction between different societies and a crucible of critical social, economic and cultural developments. It is this narrative of interaction and innovation, of accommodation and conflict that can create new vantage points on both heritage and identity. Despite the poverty of this material, there is a considerable body of existing research, which provides a starting point for a very different historical account.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|