British Assam [1826-1947]

It was only in the early years of the 19th century, weakened by internal strife and rebellion, and by a Burmese invasion that the edifice of the Ahom Empire finally crumbled. Hence arose the series of hostilities with Ava known in Indian history as the first Burmese war, on the termination of which by treaty in February, 1826, Assam remained a British possession. In 1832 that portion of the province denominated Upper Assam was formed into an independent native state, and conferred upon Purandar Sinh, the ex-Rájá of the country; but the administration of this chief proved unsatisfactory, and in 1838 his principality was reunited with the British dominions. After a period of successful administration and internal development, under the Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal, it was erected into a separate Chief-Commissionership in 1874.

The Garos, who lived to the west, were a rude people, who used to trouble the peace of the neighboring districts in quest of heads or prisoners, and, as the punitive expeditions sent into the hIlls only produced a temporary effect, a post was established under a European officer on Tura Hill in 1866, but the district was not finally pacified till 1873. The Khasi Hills were conquered in 1833, but the native rulers were left for the most part in possession of their territory, and, as no attempt has been made ,to interfere with them in any way, they acquiesced in British occupation of small portions of the country for hill stations. The inhabitants of the Jaintia Hills, which lapsed to us in 1835, were however, subjected to a moderate system of taxation, an innovation against which they protested by rising in open rebeHion in 1860 and 1862, but the revolt was thoroughly stamped out, and since that date the peace of the district had not been disturbed.

The Naga and Lushai Hills were, like the Garo Hills, occupied in order to protect the plains from the raids of the hillmen. The Nagas showed extraordinary persistence in their resistance to British arms, and no less than three Political Officers came to a violent end, two being killed by the hillmen and one being accidentally shot by his own sentry.

The British moved into Assam to secure the eastern flanks of their empire. They stayed on to develop commercial interests in tea, oil, coal and timber. The map of the North East was drawn and redrawn many times to suit the interests of administration, commerce and empire. At Independence, the province of Assam embraced almost the entire region. This legacy was modified in succeeding decades as hill States emerged to meet the aspirations of their people.

In 1838 the first twelve chests of tea from Assam were received in England. They had been injured in some degree on the passage, but on samples being submitted to brokers, and others of long experience and tried judgment, the reports were highly favorable. It was never, however, the intention of Government to carry on the trade, but to resign it to private adventure as soon as the experimental course could be fairly completed. Mercantile associations for the culture and manufacture of tea in Assam began to be formed as early as 1839; and in 1849 the Government disposed of their establishment, and relinquished the manufacture to the ordinary operation of commercial enterprise. Tea cultivation steadily progressed in Assam, and firmly established itself as a staple of Indian trade.

Assam was constituted into a Chief Commissioner's province on 6 February 1878 by separating it from Rengal by an order of the Government of India. It was the smallest province with 77,500 square miles, more than half of which was made up of hills and sparsely populated frontier tracts. The Brahmaputra Valley and the Surma Valley contained over six and half millions out of the Province’s total population of about seven and half millions.

Wild elephants abounded and committed many depredations, entering villages in large herds, and consuming everything suitable to their tastes. Many are caught by means of female elephants previously tamed, and trained to decoy males into the snares prepared for subjecting them to captivity. A considerable number were tamed and exported from Assam every year, but the speculation was rather precarious, as it was said about twice the number exported are annually lost in the course of training. Many were killed every year in the forests for the sake of the ivory which they furnish; and the supply must be very great which can afford so many for export and destruction without any perceptible diminution of their number.

The rhinoceros was found in the denser parts of the forests, and generally in swampy places. This animal was hunted and killed for its skin and its horn. The skin affords the material for the best shields. The horn was sacred in the eyes of the natives. Contrary to the usual belief, it was stated that, if caught young, the rhinoceros was easily tamed, and became strongly attached to his keeper. Tigers abound, and though many are annually destroyed for the sake of the Government reward, their numbers seemed scarcely, if at all, to diminish. Their destruction was sometimes effected by poisoned arrows discharged from an instrument resembling a cross bow, in which the arrow is first fixed, and a string connected with the trigger was then carried across the path in front of the arrow, and fastened to a peg. The animal thus struck was commonly found dead at the distance of a few yards from the engine prepared for his destruction.

Among the most formidable animals known was the wild buffalo, which was of great size, strength, and fierceness. Many deaths were caused by this animal, and a reward was given for its destruction. The fox and the jackal existed, and the wild hog was very abundant. Goats, deer of various kinds, hares, and two or three species of antelope are found, as are monkeys in great variety. The porcupine, the squirrel, the civet cat, the ichneumon, and the otter were common. The birds are too various to admit of enumeration. Wild game was plentiful; pheasants, partridges, snipe, and waterfowl of many descriptions made the country a tempting field for the sportsman.

The Assam districts formed what was called a non-regulation province — i.e., one to which it had not been found expedient to extend the British system of government in its strict legal entirety. Each district, instead of being under a judge and a magistrate-collector, with their separate sets of subordinates, was managed by a deputy-commissioner, in whom both the executive and judicial functions were combined. It was essentially a province yielding very little revenue to Government, and administered as cheaply as practicable.

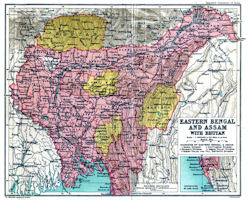

In 1905 when Bengal was partitioned, Assam, together with the eastern half of Bengal was convertsd into one Lieutenant-Governorship, known as Eastern Bengal and Assam. In 1910 the partition of Bengal was annulled and once again Assam beoame a Chief-Commissioner’s province. Like almost all the provinces of India, Assam was not formed into a homogeneous province on the basis of ethnological, linguistic or cultural factors. Political, military and administrative exigencies shaped the political map of Assam.

In 1905 when Bengal was partitioned, Assam, together with the eastern half of Bengal was convertsd into one Lieutenant-Governorship, known as Eastern Bengal and Assam. In 1910 the partition of Bengal was annulled and once again Assam beoame a Chief-Commissioner’s province. Like almost all the provinces of India, Assam was not formed into a homogeneous province on the basis of ethnological, linguistic or cultural factors. Political, military and administrative exigencies shaped the political map of Assam.

As a consequence of twelve decades of British rule, the State of Assam at Independence inherited an economy and infrastructure that served largely colonial interests. It was dominated by extractive industries, and by the interests that owned and managed them. These included the tea, oil, coal, timber and plywood industries. These industries brought prosperity, in fact riches, to their almost exclusively British owners. The tenor of Assam’s economy was however substantially unchanged from that of the last years of Ahom rule, best described as a coalition of rural, largely self-sufficient village communities, with few linkages to the organised sector developed by British economic interests.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|