French Presidential Election - 10 April 2022

A year ahead of presidential elections, poll after poll puts President Emmanuel Macron in a 2022 rematch against far-right leader Marine Le Pen. But French voters said they don't want to relive that 2017 duel a year from now. And history, at least, was on their side: France's presidential elections are often rife with spectacular surprises.

In 2017, Macron's victory was the last in a series of improbable plot twists. As a never-before-elected centrist, Macron, then only 39, mounted an unlikely bid for the presidency as an independent at the head of his own fledgling movement, famously seeing off long-established parties to make it to the presidential run-off. His meteoric rise culminated in beating the populist Le Pen in her second bid for power. He scored 66.1 percent of the vote to her 33.9, becoming the youngest president ever elected in France. Macron's tour de force left traditional parties reeling, a state of disarray from which they have yet to recover.

Four years on, France had weathered storm after storm of disquiet and dissent – deadly terrorist attacks, fiery Yellow Vest protests, a pension reform revolt that shut down large swaths of the country and a once-in-a-century pandemic. And yet "The battlefield remains outrageously dominated by the two 2017 finalists," the Journal du Dimanche said in april 2021, after polling it commissioned from the Ifop firm indicated a likely Macron-Le Pen rematch. Testing 10 different first-round hypotheses all brought the same result, with Macron ultimately topping Le Pen 54 to 46 percent in the run-off. "No other configuration but the Macron-Le Pen duel seems, for the moment, plausible," the weekly concluded.

Le Monde published a similar survey outcome, with the 2017 "finalists comfortably ahead in every scenario envisaged" in a panel of 10,000 voters polled by the Ipsos firm, with the incumbent topping his populist rival 57 to 43 percent in the run-off. "The Macron-Le Pen duel, for the moment, trounces every other alternative," the newspaper said.

A vast majority in France – 70 percent in another Ifop poll – said they didn't want a Macron-Le Pen replay next year. But so omnipresent was the polling on that scenario that nearly half (48 percent) of those surveyed by the Elabe polling firm even deemed Le Pen "certain or probable" to win the presidency in 2022, up seven points in a six-month span.

Specialists said the Covid-19 crisis had the effect of "congealing" the political landscape. Aspiring challengers – and there were many – had made little discernible headway in a race seemingly frozen in time. And the French voters they sought to persuade didn't quite have their usual taste for it. The 10,000-voter Ipsos panel showed 63 percent were interested in the election compared to 71 percent in May 2016, a year ahead of the last election.

But those whose job it is to monitor the political landscape suggesedt this eerie equilibrium was an optical illusion. France's 2022 election was different for its very unusual constraints but also because it could break wide open at any time, depending in large part on how and when the pandemic winds down in France. "That is what is going to be interesting, too; it's that [a race] has never been so open and volatile," political consultant and Sciences Po professor Philippe Moreau-Chevrolet told FRANCE 24 29 April 2021.

"The pandemic is delaying the moment for presidential debate," political historian Christian Delporte told FRANCE 24. "We are in a state of very, very great uncertainty. And the very fact that Macron's election reconstructed a political family clouds things considerably. We can imagine that this election campaign sorts itself out very late and spurs the emergence of someone," said Delporte, a professor of contemporary history at the University of Versailles.

France's presidential election is "very, very distinctive", Delporte explained. "Candidates have never, since the 1980s, had a high score in the first round. So it all hangs on very, very little." Little more than a fifth of the vote can clinch a place in the final. In the first round of 2017's presidential election, for instance, Macron scored 24.01 percent and Le Pen 21.3 percent to advance to the run-off. Close behind, the third- and fourth-place finishers' race was over, with 20.01 percent and 19.58 percent, respectively.

No French incumbent in 40 years has won re-election on his record – the only presidents to win a second term did so running against sitting prime ministers from the opposition that they could readily hang the blame on, which is not the case for Macron. France's track record is clear: surprises are the norm. For generations, the likeliest pairing of candidates a year out from any French presidential election has hardly ever made it to the following May as the final two sparring partners on the ballot. The French twist, up to and including Macron's uncanny 2017 win, has been a cinch.

A year before Macron's election, Socialist incumbent François Hollande had yet to rule out a bid for re-election. Macron's fledgling independent movement En Marche was merely days old. Pollsters were still testing Macron, Hollande's former economy minister, as a candidate for the Socialist Party. But even then, the future president was not expected to make the 2017 run-off; Le Pen and ultra-favourite conservative former prime minister Alain Juppé were well out in front.

What followed was a veritable soap opera of surprises. The unpopular Hollande threw in the towel before the race. Macron went rogue. Juppé lost the conservative primary to fellow former PM François Fillon. Touting himself as a paragon of integrity, Fillon looked like a shoo-in for the Élysée Palace – until he and wife Penelope were disgraced by a fake-jobs scandal. In beating established parties to the run-off and easily beating Le Pen to the presidency, Macron was said to have pulled off "the heist of the century".

Surprises may be what a French presidential contest is made of, but 2022 was a different beast on several fronts. Until the Covid-19 pandemic, those surprises were rooted in mass rallies, grassroots lobbying, shaking hands and kissing babies – all unfeasible for now. Before Macron, the contests were also the domain of relatively robust political parties, the same mainstream forces that now still lie in tatters. Until then, Le Pen's National Rally party (the former National Front) was a political bogeyman that could unite disparate forces to keep it out of power. But even that was changing.

As France lingered near the peak of the third wave of a pandemic that has left more than 100,000 dead – still under curfew and with public gatherings curtailed – old-fashioned campaigning was a distant prospect at best. Half a dozen hopefuls on the left and as many on the right either declared bids or pointedly expressed interest. Others, like Macron's ever-popular former prime minister Édouard Philippe touting his new book or leftist icon Christiane Taubira, let speculation swirl freely about their presidential potential. But with pandemic restrictions still in place, was it possible for newcomer candidates to gain traction or even emerge victorious, à la Macron?

One case in point: Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo. One of the few Socialist success stories in the party's glum recent past, Hidalgo aimed to broaden her renown beyond the capital with her personal "tour de France" this spring before officially throwing her hat in the race. But she had to pause that project as infections climbed again. Could yesteryear's outsiders, like Ségolène Royal or Macron himself, have risen to prominence without networking in the flesh?

"Since France has yet to ascribe to a zero-Covid strategy, a campaign that plays out as usual with big rallies isn't conceivable. It will be excessively complicated. Politicians will be tempted to do it, but there's reality," Moreau-Chevrolet told FRANCE 24 29 April 2021. His latest book was a graphic novel about a consultant charged with helping a popular TV star run for president. Moreau-Chevrolet said the circumstances created unusual opportunities for outside challengers. "We run the risk of having more of a virtual campaign for 2022," he said. That's what makes it possible to imagine just about any hypothesis, any combination. Because with that type of campaign, if it's really digital, we can easily imagine in a few weeks or months things changing radically for one or the other candidate."

"The situation will be new and very fragile, because people will literally be deciding alone, at home, through social networks, with a larger conspiracy-theory component at work. So it's hard to imagine," the political analyst said. "That's why the serious pollsters say the situation is frozen. There are far too many unknowns and we cannot exclude last-minute surprises."

After all, a presidential campaign in France is nothing like its multi-billion-dollar American equivalent. The run-up is shorter and, with a strict €22.5 million spending cap for a finalist, the bar to entry is much lower. "People can say to themselves, hey, there's an opportunity here to win the election on a really virtual campaign, where someone even with a bit of a marginal or divisive profile can manage to unite a quarter of public opinion," Moreau-Chevrolet said. "It's not unreasonable to think that could work. It's not crazy. You need, what, 10 million euros to get off the ground? That's findable because Macron found it. You'd need a clever campaign. And the ideas aren't lacking, especially among the outsiders."

If, and when, French voters deem that France had successfully emerged from the pandemic was also critical. Right-wing entrepreneur and former MEP Philippe de Villiers speculated that his one-time ally Macron would be in no position to bid for a second term after Covid-19. "When you have locked away a people for a year, the people remember it," he told BFM TV. He noted that Winston Churchill, who steered Britain through World War II, failed to win re-election. “When your name is associated with misfortune, you leave with the misfortune," De Villiers said.

Moreau-Chevrolet, for his part, believed Macron mismanaged the Covid-19 crisis with a "semi-populist" approach of light lockdowns and an initially cautious vaccine roll-out that has only prolonged the agony. He said this approach may wind up costing the president a key part of his base. "Macron's appeal to elites is a real issue," said Moreau-Chevrolet. "Many elites have friends in London, in Tel Aviv, in New York," he noted. "It will be very, very difficult to calmly evaluate the French government's actions if we see life getting back to normal in New York, London and Tel Aviv while in Paris we are still in a sort of Third World. It will not go over well."

Will an eventual easing of the pandemic finally ring in the roaring ‘20s or find a country licking its wounds? Once the crisis is well and truly past, would the French be willing to let bygones be bygones? It depends, said Delporte. Public opinion surveys showed the French were, of course, preoccupied by the pandemic, but also with social and economic issues, the historian observed. "If we exit the pandemic, say, in the autumn and we have a cascade of company bankruptcies [after emergency subsidies are withdrawn] and unemployment rises, it will be very, very hard for Macron," he said, adding that such a scenario could open a path for ex-PM Philippe to step in as a recourse candidate.

Delporte said the real indicator to watch ahead of an election is a public opinion gauge called the barometer of French morale. "It is never wrong. That can show us the result of the campaign, of the election," Delporte said. "Right now, morale isn't very good. But it can be explained by the pandemic. But we'll need to see, when the pandemic is over, if coming out of it makes people more optimistic or not. If an economic and social crisis takes over from the pandemic, it will necessarily turn [the tide] against Macron."

Macron's master stroke in 2017 – winning office and poaching talent from the left, the right and civil society to govern – proved one didn't need a long-entrenched party machine to win the presidency. But it also left existing parties fragmented, soul-searching shells of themselves. Since 2017, Macron tacked to the right, leaving political space to his left unclaimed. But backbiting leftist forces in France remain unreconciled and disjointed, threatening to split that vote between far-left Jean-Luc Mélenchon of La France Insoumise (France Unbowed), the Socialist Party (PS) and the green EELV party, contending with its own internal divisions.

Efforts we made to unite the left – a recurring challenge in French elections akin to herding cats. But former Socialist presidential candidate Benoît Hamon, who left the party after scoring a humbling 6 percent in the first round in 2017, got straight to the point at the left's stage-managed would-be peace talks at a Paris Holiday Inn. "If La France Insoumise isn't in it, this thing isn't going to work. We've done joint PS-EELV nominations before and that isn't a unified nominee," Le Monde quoted Hamon as saying.

Meanwhile, the conservative Les Républicains – from whom Macron plundered both of his successive prime ministers and which saw two of its luminaries, Fillon and Sarkozy, successively convicted on corruption charges – found itself with a glut of potential nominees, but no agreed method for choosing one. Some wanted a party primary, despite divisive past experience. Former cabinet minister Xavier Bertrand was against a primary, counting instead on polling highest and winning re-election as president of the northern Hauts-de-France in upcoming June regional elections. Having gambled on declaring his Élysée bid early, Bertrand stood a distant third in polls after Macron and Le Pen but still ahead of his conservative rivals.

And the far-right National wassn't polling as low as the political bogeyman it once was. A decade after taking the reins from her rabble-rousing father, Marine Le Pen arguably managed to "de-demonise" the party in public opinion to a significant degree while dropping marginalising ideas like leaving the European Union or the euro currency.

"Never, a year ahead of the vote, has a National Front (now the National Rally) party candidate ever obtained this kind of score," Ifop pollster Frédéric Dabi told the Journal du Dimanche, referring to the April poll that put Le Pen at 46 percent in a 2022 run-off. Her party even ranks ahead of any other in the 25-to-34 age range – "these young people who aren't managing to get a foot in the door, who will pay the devastating consequences of the economic crisis", as Dabi told Le Monde.

The daily Libération spurred controversy with a front-page report on the left-wing voters who would rather abstain next May than choose between Macron and Le Pen, suggesting holes were appearing in the united front that long saw French voters of all stripes turn out to keep the far right from office.

France's hard-left leader Jean-Luc Mélenchon was accused of reckless speech and fuelling conspiracy theories on 07 June 2021 after he predicted there would be a "serious incident or murder" designed to manipulate voters ahead of next year's presidential election. Mélenchon pointed to a pattern of violent incidents dominating headlines in the run-up to recent presidential contests. "You'll see, in the last weeks of the presidential campaign, we'll have a serious incident or a murder," the fiery head of the France Unbowed party warned, citing earlier examples.

Mélenchon, who took 19% of the ballot in the 2017 presidential race, also drew criticism for pushing the theory that President Emmanuel Macron was an invention of shadowy and powerful interests who control the country and that next year's election had been "written in advance". Referring to Macron's surprise victory four years ago, he said: "In every country of the world, they've invented someone like him, who comes from nowhere and who's pushed by the oligarchy."

A grassroots movement sprang up on the French left that was looking to avoid another showdown between French President Emmanuel Macron and far-right leader Marine Le Pen, seen by many as the inevitable rematch in France’s 2022 presidential election. By uniting the left and the Greens behind a single candidate, the nascent movement hoped to offer a viable alternative. But not everyone was convinced. Among the founders of the Rencontre des Justices (roughly, Meeting for Justice) collective behind the primary were Mathilde Imer, who helped establish the Citizens' Climate Convention on environmental action, and Samuel Grzybowski of the association Coexister, which supports interfaith dialogue. The group received the support of 178 left-wing and green MPs on July 30. They also had the backing of a number of well-known figures including former presidential candidate Noël Mamère of the Green party, noted French climatologist Jean Jouzel and actress Juliette Binoche. The organisers believed that the same citizens who have mobilised for such causes in recent years might be able to form what they call a "justice league" in the face of the "right-wing" and "neoliberal" blocs represented by Le Pen and Macron, respectively. But despite resolute optimism, reality can be cruel.

France's Greens on 28 September 2021 chose Yannick Jadot, a 54-year-old member of the European Parliament, as their candidate to challenge President Emmanuel Macron in the presidential election. Joining an increasingly crowded field of hopefuls, Jadot vied with the Socialist mayor of Paris Anne Hidalgo and far-left contender Jean-Luc Melenchon of the France Unbowed party for votes on the left of French politics. Despite stunning successes in 2020 local elections -- which saw Greens claim control of key city halls including Bordeaux and Lyon -- the Europe Ecology The Greens (EELV) party had yet to make a major impact at a national level.

French commentator Eric Zemmour, an outspoken opponent of immigration despite his immigrant background, gained political notoriety from anti-Muslim hatred and anti-migrant incitement. Before even officially announcing his candidacy in the 2022 French presidential elections, one November 2021 poll placed Zemmour at 16%. This would have translated into a second-round run off between him and current president Emmanuel Macron, knocking out far-right candidate Marine Le Pen. No poll, however, showed him coming even close to winning the presidency. Zemmour sat firmly to the right of his rival Le Pen. He has criminal convictions for inciting racial hatred and is an open proponent of the “great replacement” conspiracy theory. This suggests white people are being ethnically cleansed by Muslim migrants and Jewish puppet-masters. The 63-year-old is a native of the Parisian suburbs and the descendent of Berber Jews who moved from Algeria to France during the French-Algerian war in the 1950s.

Unlike Le Pen, whose notoriously poor performance in a 2017 debate against Emmanuel Macron was nothing short of an embarrassment to her and her party, Zemmour was a seasoned television professional endowed with both the appearance of intellect and the gift of gab. He has said that unaccompanied migrant children from Africa and the Middle East are all killers, rapists and thieves, and that “jihadists were considered to be good Muslims by all Muslims”. He also promotes the racist conspiracy theory that Europeans are gradually being replaced by immigrants.

Zemmour, who describes himself as a Gaullist and a Bonapartist, argues in his 2014 book “The French Suicide: The 40 Years that Defeated France,” that neoliberalism has put France into decline; that high divorce rates have led to sexual desperation and a crisis of virility among white men; and that, since the fall of Napoleon, “France is no longer a predator but prey”. Women, he wrote, are the victims of consumerism and, at their cores, long to be dominated by men.

Zemour had no real political experience, nor did he have the support of a party behind him, nor even a cadre of well-funded backers, as did Macron when building his fledging party. And while he was full of criticism for the path France has taken since the 1960s, he had yet to delineate a path toward fixing what he believes to be the nation’s problems. Zemmour is candid about his admiration for Donald Trump's US campaign in 2016. "He succeeded in bringing together the working classes and the patriotic bourgeoisie. That's what I've been dreaming about... for 20 years," Zemmour told the LCI channel. Zemmour has suggested similarities between the ex-US president's chief concerns and his own: immigration, de-industrialisation, as well as opposition to "the politically correct". "That means the media, judges, the cultural elite," he said.

Eric Zemmour announced on 30 November 2021 that he would run for president in the following year's election, staking his claim in a video peppered with anti-immigrant rhetoric and warnings France must be saved from decline. Zemmour, 63, was the most stridently anti-Islam and anti-migrant of the challengers seeking to unseat President Emmanuel Macron in the April 2022 vote. His formal entry into the race -- anticipated for weeks -- adds another element on the far-right to the campaign, alongside its traditional leader Marine Le Pen. But it remained to be seen if he would maintain the momentum of recent weeks. He said he had joined the race "so that our daughters don't have to wear headscarves and our sons don't have to be submissive".

Opinion polls in September and October 2021 briefly showed him as being the best-placed candidate to topple Macron, who had then yet to declare his bid for a second term but was widely expected to do so early the following year. But Zemmour's momentum appeared later fizzled. Later surveys put him third in the first round of the election at 14-to-15 percent, behind Macron and Le Pen. Analysts say it was Le Pen who could benefit from his entry by making her look more reasonable.

Macron eventually faced the far right’s Marine Le Pen in a presidential run-off on April 24 after leading the first round on Sunday with 27.6% of the vote to Le Pen's 23.0%, according to an Ipsos exit poll. Macron was projected to win 27.6% of the vote, ahead of Le Pen (23.0%) and third-placed Jean-Luc Mélenchon (22.2%), according to projections by Ipsos Sopra Steria. Some 48.7 million voters were called to the polls for the first round. By 5pm, 65 percent of registered voters had cast a ballot, down 4.4 points on the previous election in 2017. Macron will be prevented from seeking re-election in 2027 under French term limits. His upstart centrist party has produced no obvious successors, meaning the jockeying has already begun to take his place.

Even more than in 2017, Le Pen’s camp is likely to frame the second-round contest as a battle between globalised urban elites and France’s marginalised peripheries. In that respect, it is perhaps noteworthy that the two most powerful figures in the Paris region – the capital’s mayor, Anne Hidalgo, and the head of the region, Valérie Pécresse – suffered a shellacking at the polls, recording by far the worst results in the history of their respective parties.

Pécresse’s dismal 4.8% was a whopping 15 points shy of the tally reached by scandal-plagued François Fillon five years ago. Early on in the campaign, Pécresse’s bid was hampered by a botched rally from which she never recovered. She was also fatally squeezed in between Macron’s pro-business pitch and hardliners on the far right.

Still, Pécresse fared significantly better than her Parisian rival Hidalgo, representing the other mainstream party that once dominated French politics. The Socialist nominee spent much of her airtime attacking Mélenchon in an increasingly desperate attempt to stem the haemorrhage in support. She was projected to win a dismal 1.8% of the vote, setting another milestone in the demise of a party that controlled the presidency, both chambers of parliament and all but one of France’s mainland regions just 10 years earlier.

Presidential - Round 2

It was an outcome predicted by many, and a repeat of the same vote five years ago. Incumbent President Emmanuel Macron and far-right leader Marine Le Pen on Sunday came out on top in the first round of the French presidential election, securing their places in the runoff that will be held in two weeks.

Virginie Martin, a research professor at Kedge Business School, said the runoff is a consequence of an increasingly polarised France, with each of the top two candidates presenting two different images of society. “Macron destroyed the left-right divide,” she said, in reference to the president upending France’s established political system with his 2017 election win. “As a result, the oppositions are moving to the far right and far left. This is a problem.”

Macron – nicknamed the president of the rich – embodies the France of educated, wealthy people who support globalisation, NATO and are pro-Europe. On the other, Le Pen represents the blue-collar working class who have reservations about Europe and NATO. The rematch between the pro-Europe economic liberal and the populist-nationalist is an indictment of a French political establishment that has failed to renew itself in the five years since Macron came to power.

Having promised on his election in 2017 to ‘remove the reasons for voting for the extremes’, Macron finds himself confronting now a devastated political landscape where only the extremes [of both right and left] present an alternative to his centrist administration, with far-right candidates the weightiest grouping in this election.

A Le Pen win would have sent political shockwaves within Europe, pivoting France to join the list of other countries ruled by right-wing populism. The “Republican front” against Le Pen, which worked well in 2017 after people rallied for Macron to prevent the far-right leader from winning, looks less sturdy now, especially with far-right candidates, including Zemmour and sovereign nationalist Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, securing as a whole a third of the vote. Furthermore, the far-right political spectrum has widened over the past five years, with Le Pen presenting herself as a less divisive figure.

In 2017, a reliable French electoral trope known as the Front Républicain (Republican front) – the propensity for disparate political forces to band together at the ballot box to ward off the threat of any far-right challenger - was sure to kick in. And indeed Macron, the centrist political neophyte, never before elected to any office, would go on to win 66.1 percent to Le Pen's 33.9 percent in 2017 to become France's youngest president.

But five years on, the incumbent would be wise to temper the festivities. After five years of Macron rule that left mainstream conservatives in tatters and leftists exasperated, observers say the Republican front isn’t certain to sweep to the rescue this time and carry Macron to a second term. Indeed, on 08 April 2022, the last day polls could be released before the weekend vote, Le Pen finally closed the gap on Macron for just this prospective final; the Elabe firm found Macron polling at 51 to Le Pen's 49. On Sunday night, another poll by the Ifop firm just after polling stations closed showed the same 51-49 gap, while Ipsos had Macron at 54, with a three-point margin of error. Each puts the far right, for the first time, a stone’s throw from the Élysée Palace.

Les Républicains' Pécresse and the Socialist Hidalgo, conceding defeat minutes after polling places closed at 8pm, were the first to declare they would vote for Macron in the run-off to keep Le Pen from power. Pécresse warned of “disastrous consequences” should France fall into far-right hands; Hidalgo called for a Macron vote “so that France does not fall into hatred”. They were the first shots over the bow for the Republican front, sure, but from two deeply wounded parties on the verge of a reckoning. Greens candidate Yannick Jadot and Communist candidate Fabien Roussel added their featherweight to the front, too, with appeals for their low single-digit support to back Macron over Le Pen in the second round.

Meanwhile, in what may be his swan song on the French presidential stage, Jean-Luc Mélenchon appealed only for the 22.2 percent support he won on Sunday night – nearly three points up on his 2017 score – not to cast a single vote for Marine Le Pen. “I know your anger,” Mélenchon told supporters in his concession speech. “Do not let yourselves get carried away with it to the point of committing definitively irreparable errors,” he pleaded. But with his La France Insoumise ("France unbowed") voters widely seen as most likely to sit out the run-off, the cantankerous 70-year-old far-leftists stopped well short of endorsing Macron and will have done very little to quell any frayed nerves in Macron’s camp.

Macron won a second term in office, according to initial projections by pollster IPSOS with 58.2 percent, compared to 41.8 percent for his opponent, far-right leader Marine Le Pen. Macron was the first sitting French president to have been re-elected for 20 years. He also became the only president under the Fifth Republic to have been returned to office by direct universal suffrage while holding a parliamentary majority. Macron secured a double-digit victory over LePen at a time when his approval rating was 36%.

National Assembly

Legislative elections in France were held on 12 and 19 June 2022 to elect the 577 members of the 16th National Assembly. Following the 2017 legislative election, President Emmanuel Macron's party La République En Marche! (LREM) and its allies held a majority in the National Assembly (577 seats). The La République en Marche group had 308 deputies; the Democratic Movement (MoDem) and related parties has 42 deputies; and Agir ensemble, which was created in November 2017, had 9 deputies.

Switching the electoral system to proportional representation in part has been discussed. Although the proposal to have part of Parliament elected with a proportional representation system was included in Macron's platform in 2017, this election promise was not fulfilled. A similar promise was made by François Hollande when he campaigned for the presidency in 2012.

The 577 Members of Parliament (MPs), also known as deputies, who make up the National Assembly are elected for five years by a two-round system single member constituencies. A candidate who receives an absolute majority of valid votes and a vote total equal to 25% of the registered electorate is elected in the first round. If no candidate reaches this threshold, a runoff election is held among candidates who received a vote total equal to 12.5% of the electorate. The candidate who receives the most votes in the second round is elected.

The French presidential election results on 26 April 2022, gave Emmanuel Macron a comfortable victory – setting the stage for the “third round”, as many in France call the parliamentary polls taking place on June 12 and 19. His populist adversaries were keen to seize control of parliament and scupper Macron’s second term – but analysts said victory for the president’s supporters was the likeliest outcome, although it would require a deal with France’s traditional conservative party.

Following Macron’s reelection in May, his centrist coalition sought an absolute majority that would enable it to implement his campaign promises, which included tax cuts and raising the retirement age from 62 to 65. The leftists’ platform included a significant minimum wage increase, lowering the retirement age to 60, and locking in energy prices.

Extreme-left firebrand Jean-Luc Mélenchon took a similar approach – telling supporters soon after Macron won that “the third round begins tonight” and that “another world is still possible if you elect enough MPs” from his Union Populaire outfit. Mélenchon for one had explicitly pitched himself as a candidate for Macron’s prime minister if he could somehow gain a parliamentary majority. This would mark a return to “cohabitation”, the system which kicks in when the president lacks majority support in the National Assembly and so picks a prime minister from the winning party, creating a program based on compromise between the two.

France has had no cohabitation since 2002, after which a constitutional reform kicked in moving parliamentary elections to the aftermath of presidential votes. Since then, the freshly elected (or re-elected) president’s party has sailed to victory on the coattails of their win. Thus past precedent suggests that the same dynamics that carried Macron to victory in the presidential polls will benefit his party in June.

Whereas presidents tend to carry their support into the législatives, recently defeated runners-up and third-placed candidates have tended to perform unimpressively. Le Pen won nearly 34 percent of the vote in the 2017 presidential vote's second round – before the Front National (National Front, the RN's predecessor) got just eight out of the 577 National Assembly seats in the subsequent polls. This came after she reached a strong third place in the 2012 presidential vote, but the National Front performed poorly in the parliamentary elections soon after.

Whereas Le Pen’s and Mélenchon’s parties had faltered in recent years’ parliamentary elections, traditional conservative party Les Républicains (LR) held up best when Macron’s party swept its rivals aside in the 2017 législatives, becoming the biggest opposition party despite losing a lot of seats. LR found itself in a paradoxical position after its presidential candidate Valérie Pécresse bombed at the ballot box: a negligible force in the race for the Élysée Palace, but a formidable presence at the local level after topping the polls at the 2021 regional elections. LR was also a paradoxical party on an ideological level: the party of Pécresse – whose attempt to cast Macron as a “pale imitation” of a centre-right leader made her, not him, look like the imitator – but also the party of Éric Ciotti, her biggest rival in the LR primaries, whose politics are far more like Zemmour’s than Macron’s.

Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s far-left France Unbowed (La France Insoumise or LFI) party, which came in third in the first round of the 2022 presidential election, has had 17 MPs in the National Assembly since the 2017 legislative elections. They quickly gained notice not only for their ability to create a buzz, but also for blocking certain government texts.

On May 10, 2022, France’s Greens, Communist Party and Socialist Party all agreed to form a historic alliance with the far-left France Unbowed (La France Insoumise or LFI), ahead of the June legislative elections in hopes of securing a lower-house majority. Despite its small number of members currently, LFI had been very active in the National Assembly over the past five years. It had passed 100 or so bills and more than 60 motions for resolutions, tabled more than 60,000 amendments, established four commissions of enquiry and intervened thousands of times in parliament.

"Our goal was simple: to be the first opponent and the first proposer", says Mathilde Panot, MP for Val-de-Marne and president of the LFI parliamentary group in the National Assembly. "We wanted to fight the government both by bringing the country's various social struggles into the National Assembly while making sure, each time, to propose another vision by converting our programme into legislative proposals," she continued. "For example, we are the only group that presented a counter-budget every year and a counter-management plan for Covid."

The presidential majority was worried about what would happen if a very large number of LFI MPs were to get elected during the legislative elections on 12 and 19 June. "LFI has adopted a chaos strategy. (...) There is a risk of permanent political guerrilla warfare regarding substance and form," says François de Rugy, the former ‘Macronist’ president of the National Assembly, in an article published on 16 May by L'Opinion.

French President Emmanuel Macron’s centrist alliance was expected to keep its parliamentary majority after the first round of voting, according to projections on 12 June 2922. Projections based on elections’ partial results showed at the national level, Macron’s party and its allies got about 25-26 percent of the vote. They were neck-in-neck with a new leftist coalition composed of hard-left, Socialists and Green party supporters. Yet Macron’s candidates are projected to win in a greater number of districts than their leftist rivals, giving the president a majority. Macron would need to secure at least 289 of the 577 seats to have a majority for pushing through legislation during his second five-year term. Government insiders expected a relatively poor showing in the first round for Macron’s coalition “Ensemble”, with record numbers of voters seen abstaining. Though Mélenchon’s coalition could win more than 200 seats, current projections gave the left little chance of winning a majority. Macron and his allies are expected to win between 260 and 320 seats, according to the latest polls.

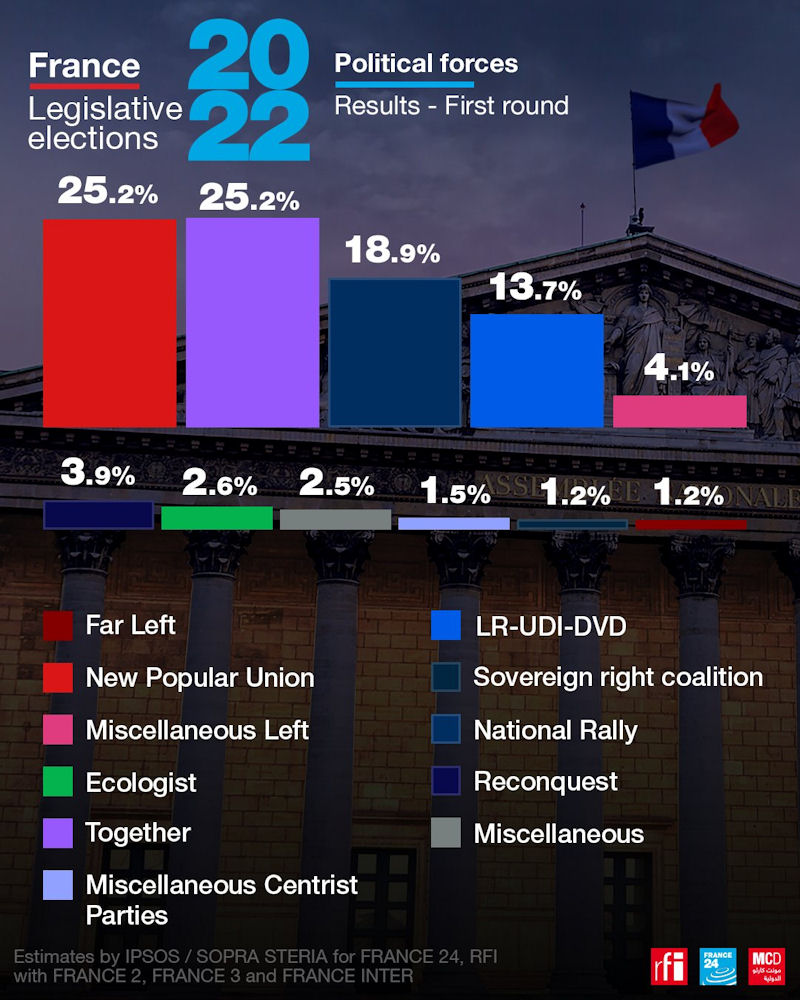

The right-wing bloc, with the Les Républicains party, the Union of Democrats and Independents (UDI) and various right-wing candidates, was left behind in the first round of the legislative elections, after obtaining 13.7% of the vote, according to an estimate. Ipsos-Sopra Steria for France Télévisions, Radio France, France Média, and parliamentary channels. The right came in fourth position, June 12, behind Nupes (25.2%), LREM (25.2%) and the National Rally (18.9%). In 2017, the right-wing bloc managed to gather 21.5% of the votes.

But French voters cast their votes to fill the 577-seat National Assembly, the French parliament’s lower-house chamber, and deprived President Emmanuel Macron of his parliamentary majority. Macron's centre-right alliance fell far short of an absolute majority of 289 seats according to estimates. The latest estimations showed Macron’s centre-right alliance Together won 234 seats, while the leftwing bloc NUPES had taken 141, more than double what the sum of its member parties had previously, but still far short of the majority it had campaigned to win and that it's leader Jean-Luc Melenchon had claimed throughout the campaign was a realistic goal.

Meanwhile, the far-right National Rally won 89 seats; its best showing ever, and nearly ten times its previous grouping in the National Assembly. Ironically, the RN's leader, Marine Le Pen, had been criticized by party members for taking time off after the presidential elections, and leaving the political stage to be taken over by LFI's Melenchon to campaign on. This absence had partly been justified on the RN's historical poor past performance in legislative elections, due as it routinely claimed to an unfavorable electoral mode of voting. With Melenchon, monopolizing the airwaves and public attention, and thus the claim to being the main opposition party, Marine Le Pen re-entered the campaign in a more active manner.

The Les Republicains party, which had been feared to become completely wiped out during these elections, nevertheless managed to salvage still around 60 seats, making them potentially a major governing partner with Macron's Ensemble/Together alliance, with possible ministerial posts to be gained as a result. One unintented consequence of the legislative elections and NUPES's rise is how the political spectrum of the National Assembly is likely to have shifted moreso to the right as a result, given the size of the RN legislative grouping and the likely need of Macron's alliance to rely on the Les Republicains to push through legislation. Reacting to the night's first estimates, Macron's Budget Minister Gabriel Attal said, "It's less than what we hoped for. The French have not given us an absolute majority. It's an unprecedented situation that will require us to overcome our divisions."

All these results nonetheless are to be put in the perspective of a very low participation rate, with 53.77% of voters not taking part in these polls.

By convention, a sitting minister who loses an election race steps down from the post in cabinet. Of the 15 ministers running, 12 won their races and three lost. The three now likely to relinquish their government jobs were: Ecological Transition Minister Amélie de Montchalin, who lost her race to a Socialist member of the NUPES (New Popular Union) coalition in the Essonne, Health Minister Brigitte Bourguignon, who narrowly lost her bid for re-election in the Pas-de Calais to a far-right National Rally candidate, and Overseas Minister Justine Benin, who lost her bid for re-election in Guadeloupe to a candidate backed by the left-wing alliance. Two ministers who had first-round deficits to make up in their Paris races – Minister for Public Services Stanislas Guerini and Junior Minister for Europe Clément Beaune – defeated their left-wing challengers to win the seats in the French capital.

NUPES (New Popular Union) candidates François Ruffin, a vocal Emmanuel Macron opponent and member of the far-left La France Insoumise, was re-elected in the Somme’s 1st District, which takes in Macron’s hometown of Amiens. Before his election to the National Assembly, the far-leftist Ruffin won a 2017 César, the French equivalent of an Academy Award, for his satirical documentary “Merci Patron!” (“Thanks Boss!”). “The country is blocked,” Ruffin told LCI television Sunday night, commenting on the night’s estimated results nationwide. “Emmanuel Macron today does not have the legitimacy to impose his platform, Marine Le Pen doesn’t have the legitimacy to impose her platform,” he said. “But it must be said that we don’t have the majority either or the legitimacy to impose out platform.”

Prime Minister Elisabeth Borne, who won her race for a legislative seat in the Calvados, pledged to get to work to reach out to potential partners to seek a "working majority" and ensure stability in France. She warned that the "unprecedented" situation of a fractured lower-house chamber represented "a risk for the country". "I have trust in all of us and our sense of responsibility," she said. "We want to continue to protect you and to ensure your security," she added, addressing voters after Macron's centre-right alliance lost the absolute majority the president had enjoyed throughout his first term in office.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|