Enver Hoxha

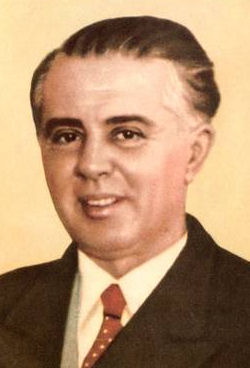

Enver Hoxha, First Secretary of the Albanian Workers' Party (AMP), was the leading Albanian Communist since the formation of the Party in 1941. Handsome in his youth, about six feet tall, Haxha had a robust build with a tendency to stoutness. Intelligent, with a great deal of personal charm and a gift for oration, he was considered egotistical, unreliable, cunning, temperamental, ruthless and possessed of driving ambition. It was said that he would subscribe to any sacrifice, immorality, crime, subservience and even personal humiliation in order to stay in power. Hoxha spoke French, Italian, Russian, English and Serbo-Croatian. Since 1945 he had been married to Neximnije (Xhuglini) Hoxha; they had at least three children.

Enver Hoxha, First Secretary of the Albanian Workers' Party (AMP), was the leading Albanian Communist since the formation of the Party in 1941. Handsome in his youth, about six feet tall, Haxha had a robust build with a tendency to stoutness. Intelligent, with a great deal of personal charm and a gift for oration, he was considered egotistical, unreliable, cunning, temperamental, ruthless and possessed of driving ambition. It was said that he would subscribe to any sacrifice, immorality, crime, subservience and even personal humiliation in order to stay in power. Hoxha spoke French, Italian, Russian, English and Serbo-Croatian. Since 1945 he had been married to Neximnije (Xhuglini) Hoxha; they had at least three children.

Prominent during World War II as a Party and resistance organizer, he emerged in the postwar period as the undisputed leader of the Albanian government and Party. Since his accession to power Borba has eliminated all threats to his position, most notably the pro-Yugoslav faction under Koci Xoxe, who was executed in 1949.

Hoxha led his country into a uniquely important position in the Sino-Soviet controversy, largely in reaction to Tito's "revisionism" and Khrushchev's de-Stalinization. In the mid-1940's both the Albanian Party and government were under strong Yugoslav influence, and the country functioned as a sub-satellite of the USSR. In 1948, when Yugoslavia was expelled from the Cominform Albania gained the status of a full-fledged satellite of the Soviet Union after Hoxha vehemently denounced the Yagoslava and embarked on a series of purges of so-called "Titoists."

A new phase in Albanian foreign relations began with Kbrushebev's reconciliation visit to Yugoslavia in May 1955. If he followed the new Soviet line, Hoxha faced the prospect of personal humiliation in retracting seven years of extreme anti-Yugoslav statements as well as the possibility of renewed Yugoslav influence over his country. Khrushchev's de-Stalinization campaign added a further dimension to the situation, since the Albanian leadership utilizes Stalinist methods to maintain control of the country.

A new phase in Albanian foreign relations began with Kbrushebev's reconciliation visit to Yugoslavia in May 1955. If he followed the new Soviet line, Hoxha faced the prospect of personal humiliation in retracting seven years of extreme anti-Yugoslav statements as well as the possibility of renewed Yugoslav influence over his country. Khrushchev's de-Stalinization campaign added a further dimension to the situation, since the Albanian leadership utilizes Stalinist methods to maintain control of the country.

Höxha then turned to China, which seemed both willing and powerful enough to protect him from Soviet pressure. However, it soon became apparent that, in return for Chinese protection, Albania would have to support China in her controversy with the Soviet Union, and Hoxha subsequently committed his country to this policy. At the first great debate on the Gino-Soviet ideological controversy, held in Bucharest in June 1960, which was attended by Kbrushchev and all other European blob Communist leaders except Hoxha.

Enver Hoxha's story began in the early years of the twentieth century. Son of a modest family, it is generally held he was born on 16 October 1908, in southern Albania, the son of a carpet merchant who was a Moslem of the Bektashi sect. Young Hoxha received his secondary education at the French Lymee in force. In 1930 he was sent on a state scholarship to study natural sciences at Montpellier University in France but a year later his scholarship was withdrawn. Leaving the University, Hoxha went to Paris where he met Paul Courtourier, chief editor of L'Humanite, the organ of the French Communist Party, and wrote anti-Zogist newspaper articles under the pen name "Lab o Malesori." Unable to find permanent employment in France, Hotha went to Brussels where he worked as a secretary at the Albanian Consulate from 1933 to 1936. He still maintained clandestine contact with Coartourier, and in the latter year he was dismissed from the Consulate for his political views.

Returning to Albania, Hoxha obtained teaching positions at the gymnasium in Tirana and later at the French Iycee at force. After the Italian invasion of Albania in 1939 he was discharged from the Lycee for his refusal to join the Fascist Party. He then moved to Tirana where he operated a tobacco kiosk which became a front for Communist cell meetings and resistance activities.

Tried in absentia and Sentenced to death by the Italian occupation authorities in October 1941, he went underground for the duration of the War. At the clandestine founding conference of the Albanian Communist Party, held in Tirana during November 1941 under the guidance of two emissaries of the Yugoslav Communist Party, Dusan Mugosa and Masan Popovic, Hoxha was named to membership on the Central Committee of the provisional Party leadership. In 1943, at the Party's First National Conference, held in Labinot, he was elected Secretary General of the first formally constituted Central Committee.

Hoxha was one of the principal organizers of the Conference of Peze, held in September 1942, in which resistance leaders of all shades of political opinion participated. This conference created the National Liberation Movement (LNC), with a Communist-controlled General Council of National Liberation, to which Hoxha was elected. At its conference of Labinot, held in July 1943, the ISC General Council created the General Staff of the Army of National Liberation of Albania (ANLA), and Hoxha became the Staff's political commissar.

Thus the Communists, under Maxha's leadership, dominated And controlled the partisan resistance movement, and as the war drew to an end, they consolidated their grip on the country and liquidated members of other resistance and opposition groups. At the Congress of Fermat in May 1944, which created the Anti-Fascist Council of National Liberation, Hoxha was named President of this Council and Commander-in-Chief of the AMA, with the rank of Colonel General. The Congress of Herat (October 1944) transformed the Anti-Fascist Council into the Albanian Provisional Government, with Hoxha assigned the dual roles of Premier and Minister of National Defense. After the withdrawal of the German forces from Albania, the new government installed itself at Tirana on 28 November 1944, and the Communist take-over of the country was virtually completed.

Upon the adoption of the new Albanian Constitution in March 1946, Hoxha gained the additional posts of Minister of Foreign Affairs and Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces. In November 1946, when the Albanian Communist Party changed its name to the Albanian Workers Party (AMP), Hoxha was re-elected Secretary General. He was elected as AWP First Secretary in July 1954, when a Central Committee plenum abolished the function of Secretary General, following the Soviet post-Stalin pattern. In July 1953, after having held the country's key military and governmental assignments for nearly a decade, he relinquished the post of Minister of Foreign Affairs and Minister of National Defense, as well as Comminder-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, to his trusted' lieutenants. A year later, in accordance with the Soviet-dictated principle of collective leadership, he gave up the Premiership to Shehu.

During the first two decades of his virtual dictatorship, Hoxha led Albania through a series of dramatic foreign policy changes. Although he was pro-Yugoslav during and immediately after the war, Hoxha became violently anti-Yugoslav and pro-Soviet following Tito's break with the Cominform in 1946. Since 1960, however, Hoxha assumed an anti-Soviet, pro-Chinese attitude, defying Moscow's ideological and political authority, and aligning his country firmly with the Communist Chinese in the Sino-Soviet dispute. It is interesting to note that Botha's break with the Soviet Union has resulted in some measure of real popular support from the xenophobic Albanian people.

Hoxha ran the only European bloc Communist leader who did not accompany Khrushchev to the meeting of the UN General Assembly in September 1960. Hoxha did, however, attend the conference of the 81 Communist Parties held in Moscow in November 1960, where he strongly supported China's policy on war and co-existence.

During 1961 Albanian-Soviet relations continued to deteriorate; Soviet economic and technical assistance to Albania was suspended, replaced largely by Chinese aid, and in December diplomatic relations between Albania and the USSR ware severed. Since then Hoxha's foreign policy was directed tovard cementing the protective ties with Peking, for Albania urgently needed continued aid as well as political protection. However, Hoxha, realistically aware of both China's geographic distance from Albania and her precarious internal economic situation attempted to improve relations with Albania's neighbors, especially Italy, to reactivate trade relations with Western Europe, and to develop trade with Near Eastern and African countries.

Envar Hoxha was inspired and hugely influenced by Stalin. Ideas that streamed from the Bolshevik revolution and were implemented by Lenin and later Stalin - including the creation of a one-party state and purging by any means one's political enemies - appealed to Hoxha. He was also drawn to the creation of a "dictatorship of the proletariat" - where the working class holds political power and nationalises the means of production.

Following in their footsteps, Hoxha embraced a centralised economy where industry and other economic activities were owned by the state. Marxism-Leninism was taught in Albanian schools, while busts of Stalin were erected in many cities. Within a short period of time, Hoxha became the absolute leader of the Communist Party (later renamed the Party of Labour of Albania) and of Albania. During his four decades in power, he prosecuted and ruthlessly eliminated every real or imagined political opponent.

Albanian communism was built on the cult of a dictator. The regime Hoxha created, isolated Albanians from the rest of the world and brought to an end not only their political freedoms but also their personal ones. People would be jailed and their families deported to internment centres. Nobody was immune.

In 46 years of its existence, the regime displaced more than 30,000 Albanians to labour camps and internment areas. About 18,000 others were imprisoned for political reasons and 6,000 were executed, many without trial. Today there are more than 4,000 people still missing - many of whom are thought to have been buried in mass graves.

In order to consolidate the violent regime, the Party created a sophisticated machine of propaganda dissemination, driven by the glorification of its leader, Hoxha. Radio, newspapers and television would describe him as the "legendary commander" who was building a new and better Albania inspired by Marxist-Leninist ideology.

Ideas such as the need to eliminate the classes in society, the need to give everyone the same chances and a secure job, and the need to protect the country from foreign enemies, especially the "evil" West, were used to justify the violence.

Hoxha was at the forefront of efforts to build his cult of personality. He wrote a total of 71 books - 13 of which are memoirs - forging and twisting many elements of his life and the country's history. Alternative sources of information were simply not available. His obsession with power without rivals led to unprecedented hostility toward religion. Imams, priests and other spiritual leaders were imprisoned and killed.

In 1967, Hoxha called on Albanians to take a stand against religion and tens of thousands obeyed, demolishing more than 2,000 religious places of worship throughout Albania. Mosques and tekkes, Orthodox and Catholic churches were vandalised and turned into communist propaganda offices, cultural centres or warehouses. In 1976 the practising of religion was banned by the Constitution and communists took pride in establishing what they called "the first atheist country in the world".

In April 1985, Hoxha died at the age of 77, from complications caused by diabetes, but the Party was prepared to save the power he had accumulated. They felt the cult of Hoxha should not end with his life and in order to keep it alive, new tools were introduced. After Hoxha's death, artists were asked to create numerous busts, statues and memorials portraiting the dictator. These creations aimed to further glorify his cult and were characterised by falsity, giant mania and lack of artistic sense.

Soon the statues of Hoxha were erected in squares and at the institutional doors of Albania's main cities. Busts were used to decorate every state office and their replicas also appeared in the living rooms of ordinary Albanians.

More ambitious projects were undertaken in Hoxha's birth town of Gjirokaster and the capital Tirana. A monument, with a statue of Hoxha seated in its centre, was built in a panoramic terrace at the entrance to Gjirokaster. Around 80 tonnes of Italian marble was used to build it. After the fall of communism in Albania in 1991, this same memorial was smashed to pieces.

In Tirana in 1988, a 12-metre-tall (39-foot-tall) statue of Hoxha was erected in the main Skerderbej square. That same year, the doors of the Pyramid opened - a massive building alongside Tirana's main boulevard destined to house a museum to memorialise the dictator's life. To this day, it remains one of the most iconic buildings in the Albanian capital.

The trials at the beginning of 1990s against high officials of the regime were a farce and nobody was convicted [for] more than five years. The Lustration was never fully implemented and none of the architects of that inhumane regime showed ever any repentance. Between 1993 and 1994 more than 20 former high officials of the Party of Labour, including the dictator's widow, Nexhmije Hoxha, were charged with corruption and misusing public funds. Although they were convicted and sentenced from three to 11 years in prison, appeal courts reduced their sentences and none remained in jail for more than five years. Nexhmije Hoxha left the prison in January 1997.

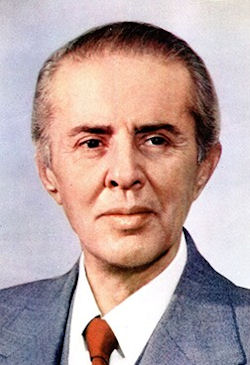

In 1996, another group, which included Hoxha's successor as head of the Party, Ramiz Alia, faced trial for crimes against humanity, including genocide charges. Although some were found guilty, a year later an appeal court nullified those sentences and set them free.

The communist-era secret service, "Sigurimi", was an infamous and much-feared structure that had in its disposal 15,000 collaborators fully committed to spying on anyone deemed suspicious, helped also by a large network of volunteers. People who had contributed to some of the most criminal aspects of the past regime were returned to public offices, including Albania's parliament.