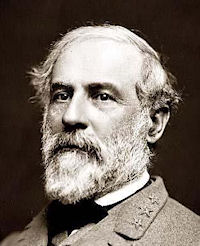

Robert E. Lee

Robert E. Lee was the most audacious commander who has lived since Napoleon. However, Alan Nolan argues that Lee was a brilliant field commander who did not understand grand strategy. According to Nolan, Lee should have pursued a defensive strategy similar to George Washington in the Revolution. Nolan argues that Lee contributed to the Confederates’ defeat through his offensive oriented strategy. Of all the army leaders and commanders including both sides, General Lee had the highest casualty rate.

Robert E. Lee was the most audacious commander who has lived since Napoleon. However, Alan Nolan argues that Lee was a brilliant field commander who did not understand grand strategy. According to Nolan, Lee should have pursued a defensive strategy similar to George Washington in the Revolution. Nolan argues that Lee contributed to the Confederates’ defeat through his offensive oriented strategy. Of all the army leaders and commanders including both sides, General Lee had the highest casualty rate.

Robert Edward Lee (1807-1870), American soldier, general in the Confederate States army, was the youngest son of major-general Henry Lee, called "Light Horse Harry." He was born at Stratford, Westmoreland county, Virginia, on the 19th of January 1807. The boyhood home of Robert E. Lee is located at 607 Oronoco Street in Old Town Alexandria. The home was a museum until it was lavishly restored as a private residence. Lee entered West Point in 1825.

Graduating four years later second in his class, he was given a commission in the U.S. Engineer Corps. In 1831 he married Mary, daughter of G.W.P. Custis, the adopted son of Washington and the grandson of Mrs Washington. In 1836 he became first lieutenant and in 1838 captain. In this rank he took part in the Mexican War, repeatedly winning distinction for conduct and bravery. He received the brevets of major for Cerro Gordo, lieut.colonel for Contre Churubusco and colonel for Chapultepcc.

After the war he was employed in engineer work at Washington and Baltimore, during which time, as before the war, he resided on the great Arlington estate, near Washington, which had come to him through his wife. In 1852 he was appointed superintendent of West Point, and during his three years here he carried out many important changes in the academy. Under him as cadets were his son G. W. Lee, his nephew, Fitzhugh Lee and J.E.B. Stuart, all of whom became general officers in the Civil War. In 1855 he was appointed as lieut.-colonel to the 2nd Cavalry, commanded by Colonel Sidney Johnston, with whom he served against the Indians of the Texas border.

Lee didn't have much wealth, but he inherited a few slaves from his mother. Lee married into one of the wealthiest slave-holding families in Virginia — the Custis family of Arlington and descendants of Martha Washington. Great-grand-daughter of Martha Washington, Mary Custis and Lt. Robert E. Lee, her distant cousin and childhood sweetheart, exchanged wedding vows in the parlor at Arlington in 1831. The marriage united two of Virginia’s “first families.” Lee was descended from a long line of famous soldiers and statesmen. His father was “Light Horse Harry”, American Revolutionary War hero, governor of Virginia, and member of Congress. Two of Lee’s father’s cousins signed the Declaration of Independence.

Custis had provided for the emancipation of his slaves in his will. Slaves were to be freed after financial obligations had been met. Custis set a deadline of five years from the time of his death for the slaves' emancipation. The slaves believed they had been promised their freedom immediately upon Custis' death. When Lee's father-in-law died, Lee took leave from the U.S. Army to run the struggling estate. Robert E. Lee, who managed the estate after Custis' death, hired out some of the slaves to raise money to settle his father-in-law's debts. This caused resentment among the slaves.

Lee was a cruel figure with his slaves and encouraged his overseers to severely beat slaves captured after trying to escape. One slave said Lee was one of the meanest men she had ever met. In 1862, freedom came to the enslaved people of Arlington when Lee executed a deed of manumission.

In 1856 Lee wrote his wife ""In this enlightened age, there are few, I believe, but will acknowledge that slavery as an institution is a moral and political evil in any country. I think it, however, a greater evil to the white than to the black race; and while my feelings are strongly interested in behalf of the latter, my sympathies are stronger for the former. The blacks are immeasurably better off here than in Africa — morally, socially and physically. The painful discipline they are undergoing is necessary for their instruction as a race and I hope it will prepare and lead them to better things. How long this subjection may be necessary is known and ordered by a wise and merciful Providence. Their emancipation will sooner result from a mild and melting influence than from the storms and contests of fiery controversy. This influence though slow is sure.""

In 1859, while at Arlington on leave, he was summoned to command the United States troops sent to deal with the John Brown raid on Harper's Ferry. In March 1861 he was made colonel of the U.S. Cavalry; but his career in the old army ended with the secession of Virginia in the following month.

Lee was strongly averse to secession, but felt obliged to conform to the action of his own state. The Federal authorities offered Lee the command of the field army about to invade the South, which he refused. Resigning his commission, he made his way to Richmond and was at once made a major-general in the Virginian forces. A few weeks later he became a brigadier general (then the highest rank) in the Confederate service.

The military operations with which the great Civil War opened in 1861 were directed by President Davis and General Lee. Lee was personally in charge of the unsuccessful West Virginian operations in the autumn, and, having been made a full general on the 3ist of August, during the winter he devoted his experience as an engineer to the fortification and general defense of the Atlantic coast. Thence, when the well-drilled Army of the Potomac was about to descend upon Richmond, he was hurriedly recalled to Richmond. General Johnston was wounded at the battle of Fair Oaks (Seven Pines) on the 31st of May 1862, and General Robert E. Lee was assigned to the command of the famous Army of Northern Virginia which for the next three years "carried the rebellion on its bayonets."

Early in June 1862, Lee was placed in command of all the Southern forces and from that time on possessed the full confidence of the Confederacy. His cooperation with Davis was hearty and sincere, and instead of charges and counter-charges there was a refreshing harmony between the President and his leading general which was never marred by dictation on the one side or complaint on the other.

General Lee was over fifty-five years of age when he was called to the head of a great army, and when he took the field against McClellan. He had passed his life, with the exception of the brief interlude afforded by the Mexican war, in the narrow and narrowing life which the United States army presents in time of peace. The relief which frontier service and fighting Indians offered to this most dull existence had been his in scant measure; for most of his days had glided away in the routine of an engineer’s duties, in which intellectual activity was restricted to subjects within the range of military need.

It may be owing to this that his first plan of campaign (or the one adopted by him at the suggestion of General Longstreet) had not the breadth of conception which should characterize the plans of a man in a position so exalted and responsible as that of the commander of a great army. For this scheme did not contemplate the permanent relief of his capital or the destruction of his adversary, and it did not comprise a field wider than that upon which the two armies were encamped. To draw the enemy out of his entrenchments by threatening his communications, and thus compel him to raise the siege of Richmond, was the utmost object of his design.

Nor did the features of the plan of campaign commend themselves to those versed in the art of war. Imperfectly manned earthworks were to constitute the sole protection of the Confederate capital during the absence of the defending army; this army would be cut off from its base by the swamps and jungles of the Chickahominy, through which, in case of disaster, there were no avenues of retreat except the narrow roads of advance, and these were overhung by high banks that were sure to afford vantage ground to the pursuer; this army, too, was to regulate its movements by those of another army which was out of sight and beyond ready communication, and the junction of these two forces was to take place in the presence of the enemy and under his fire.

Every moment after he had passed the Chickahominy, Lee would be liable to one of two things: the interposition between him and Jackson of the whole of McClellan’s army, or the advance of the Federals on Richmond through the ill-defended lines left in charge of Magruder. Moreover, in the event of the enemy’s right wing falling back, or of its being driven from the north bank of the Chickahominy, without the main body coming out of its entrenchments, the farther would Lee's own lines of communication be extended; the greater his success, the greater the concentration of his foes, until at last these foes would be congregated between Richmond and its defenders.

Jefferson Davis pointed out that the success of this movement depended upon holding good the earthworks left behind, and that the plan did not take into account the contingency of their capture. Lee was somewhat nettled at the hint that the engineer was predominating over the tactician, but made no change. This criticism of Davis's was a sound one. In fact, a glaring defect of Lee’s plan of operations was its narrowness ; it did not include remote conditions, and, worse than all, it did not provide for contingencies. For instance, it took for granted that McClellan would come out of his intrenchments in order to maintain his existing line of communications; yet McClellan was on a peninsula where the waterways were under his control and afiorded him a choice of lines on either side, and it was well known that he preferred the line of the James to any other line.

It should have suggested itself, also, that the Federal commander would be glad of an excuse to withdraw his right wing from its perilous position, particularly as, in doing so, he would he removing likewise a bone of contention between him and the politicians at Washington. Yet it does not seem to have occurred to Lee to ask himself, What if McClellan does not come out of his intrenchments ? or, What if McClellan does come out, but takes position upon a field not of my choosing?

To underrate one's adversary is as great a fault as to overrate him. At Malvern Hill Lee underrated his enemy; at Gaines’ Mill he overrated him, for at the moment when he said that “the principal part of the Federal army is now on the north side of the Chickahominy ” Porter was opposing him with barely one fourth of this army.

If General Lee, during this campaign, did not fully satisfy the high-wrought expectations of the hour in breadth of conception, adherence to plan, capacity to see things as they are, fertility of resources, and the prudence which forbids a general ever to underrate his enemy, neither did he give promise of the excellence he attained afterwards in handling troops in the immediate presence of the enemy. He did not make his mark as a tactician.

The battle of Malvern Hill affords a striking illustration of General Lee's shortcomings as a tactician; it does not present a single redeeming feature to the failure of the Confederates. The operations of General Lee in this battle will always be classed with those of the great Frederick at Torgau; the student of tactics will be rewarded for his pains in studying them by the complete knowledge he will possess of what to avoid doing. The outcome of this battle was a complete defeat for them, and not a creditable one at that. Everything upon their side was chaotic: there was no concert, no unity, no leadership. Their conduct was that of blind and senseless giants striking out they knew not whither, and hitting at random. A mass of men would rush up a deadly slope, yelling as if there were a Jericho before them to fall by mere sound.

Little can be said of Lee's career as a commander-in-chief that is not an integral part of the history of the Civil War. His first success was the "Seven Days' Battle" in which he stopped McClellan's advance; this was quickly followed up by the crushing defeat of the Federal army under Pope, the invasion of Maryland and the sanguinary and indecisive battle of the Antietam. The year ended with another great victory at Fredericksburg. Chancellorsville (Wilderness), won against odds of two to one, and the great three days' battle of Gettysburg, where for the first time fortune turned decisively against the Confederates, were the chief events of 1863. In the autumn Lee fought a war of maneuver against General Meade.

Lee's attitude toward war, as one of the human disasters of the world, was one of tolerance and strategy. He did not share the opinion of some Generals, that war is an indiscriminate assault to the death of one people against another. He prescribed and observed certain fixed modifications of conduct in war. In orders issued January 27, 1863, from his headquarters at Chambersburg, Pa., Lee defined the restrictions, or rather the ethics, of war.

"... No greater disgrace could befall the Army, and through it our whole people, than the perpetration of the barbarous outrages upon the innocent and defenseless and the wanton destruction of private property that have marked the course of the enemy in our own country. ... It must be remembered that we make war only on armed men and that we cannot take vengeance for the wrong our people have suffered without lowering ourselves in the eyes of all whose abhorrence has been excited by the atrocities of our enemy, and offending against Him to whom vengeance belongeth, without whose favor and support our efforts must prove all in vain."

The tremendous struggle of 1864 between Lee and Grant included the battles of the Wilderness, Spottsylvania, North Anna, Cold Harbor and the long siege of Petersburg, in which, almost invariably, Lee was locally successful. But the steady pressure of his unrelenting opponent slowly wore down his strength. Grant took advantage of railroad lines and new, improved steamships to move his soldiers and had a seemingly endless supply of troops, supplies, weapons, and materials to dedicate to crushing Lee's often ill-fed, ill-clad, and undermanned army.

It was for Lee to choose whether he should stand on the defensive and await events or should undertake a campaign of aggression in an effort to remove the seat of active warfare to a region farther from Richmond. He decided upon the latter course. Lee's menace to Washington was so serious that Hooker withdrew from the Rappahannock and fell back upon the capital, precisely as Lee had expected and intended. Lee immediately sent his remaining corps, under A. P. Hill, to join Ewell and ordered Longstreet also to cross into the valley. Thence the whole Confederate force was pushed across the Potomac, arriving at Chambersburg and Carlisle in Pennsylvania, on the 27th of June 1864.

Stuart, with the cavalry, made a spectacular raid around Washington. While lee's army was stretched out in a long and partially disjointed column, the unsupported head of it stumbled upon the advance of the Army of the Potomac, now under Meade, at Gettysburg, where Lee, in the absence of his cavalry, had not expected to find any force more formidable than a division or so of mounted men. An attempted reconnoissance quickly brought on a general engagement. Thus, reversing the usual practice of war, the assailing, instead of the defending, army was taken by surprise. For three days, July 1st, 2d, and 3d, there raged on of the most hotly contested and bloodiest battle of the 19th Century. At the end of that time both armies were badly crippled. Lee had not been defeated in action, but he had been balked of his purpose. His army was not broken or overthrown, but it had completely failed to accomplish the objects for which it had crossed the Potomac.

In the spring of 1864 General Grant had been made commander of all the national armies. He conceived a new plan for prosecuting the war to a successful end. He saw clearly that the vitality of Southern resistance lay in the fighting strength of the Southern armies rather than in the possession of cities or strategic positions. Lee remained with the Army of Northern Virginia at his back, and Grant clearly understood that there could be no successful issue of the war until this force should be crushed. As he himself expressed it, he determined to make Lee's army, rather than Richmond, the sole "objective" of the campaign.

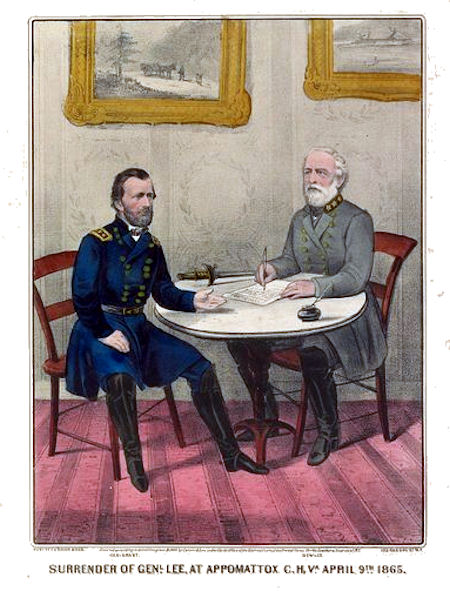

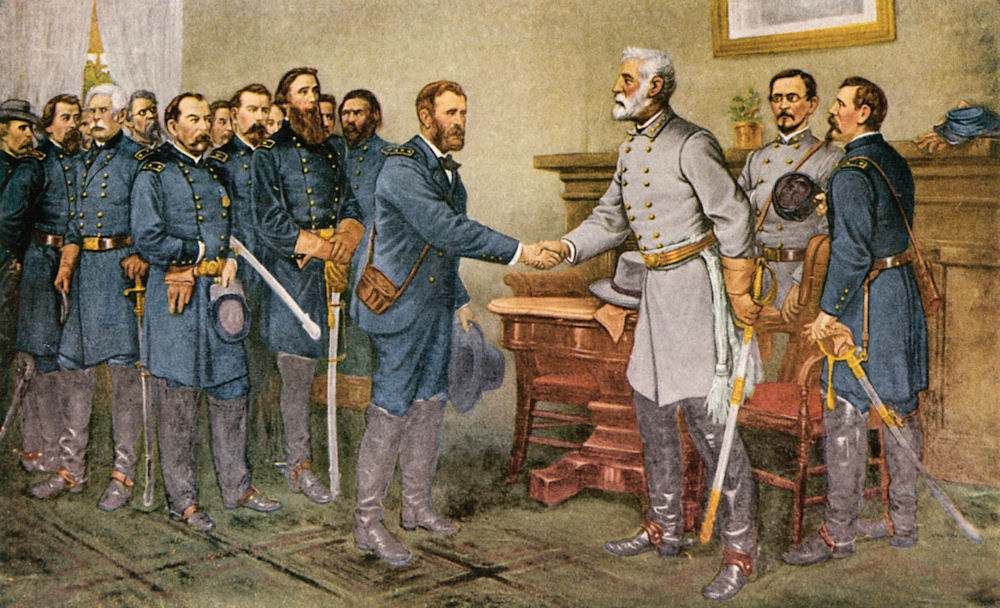

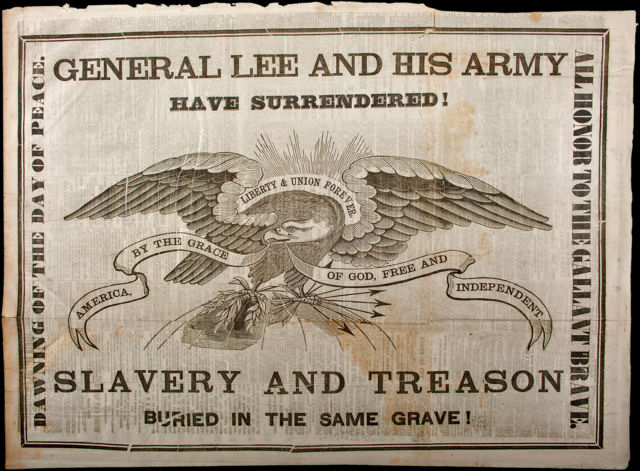

At last with not more than one man to oppose to Grant's three, Lee was compelled to break out of his Petersburg lines (April 1865). A series of heavy combats revealed his purpose, and Grant pursued the dwindling remnants of Lee's army to the westward. Headed off by the Federal cavalry, and pressed closely in rear by Grant's main body, General Lee had no alternative but to surrender. At Appomattox Court House the career of the Army of Northern Virginia came to an end. Lee's farewell order was issued on the following day, and within a few weeks the Confederacy was at an end.

For a few months Lee lived quietly in Powhatan county, making his formal submission to the Federal authorities and urging on his own people acceptance of the new conditions. In August he was offered, and accepted, the presidency of Washington College, Lexington (now Washington and Lee University), a post which he occupied until his death on the 12th of October 1870. He was buried in the college grounds.

If Lee drew his sword with a reluctance which others did not share, he wielded it with a skill which no other American has displayed. With inferior forces at his command, with his inferiority increasing as the years rolled by, he proved again and again his superiority in the field, for he brought to the campaign not merely the wasting armies which the South could alone recruit, but the genius which triumphed over difficulty and plucked success out of danger.

In all that constitutes generalship Grant was inferior to Lee. His greatest achievements—the capture of Fort Donnelson and Vicksburg—were won against inferior commanders; and, though he wore down Lee in the end by the process of attrition, he never showed himself his equal in a single portion of the campaign. He was a man of blood and iron, whose will could not be shaken by the temptations arising from previous indulgence, or by the bloodshed which would have staggered other men. He set himself his task, knowing the cost that it would entail, perhaps conscious—for it is his best excuse—that concentrated slaughter is, on the whole, less wasteful of life than protracted warfare.

Lee's critics of the years immediately following the Civil War claimed that as a soldier he was not always vigorous enough. He was never known to put a spy to death, and his clemency towards deserters, usually men who were distraught by letters from home full of distressing stories of hunger, was marked. He was a man who declined to mistrust his fellow-man for unfair or unjust conduct.

Unquestionably tender-hearted, the General commanding the Confederate Forces was a soldier of the old school. He always slept in a tent, for fear of disturbing the occupants of houses he might have used for headquarters. His mind was never wholly in the rage of war; he refused to smother his human instincts toward his "enemies"; he was keenly susceptible to the duty he owed others.

Lee had no sympathy with the Northern abolitionists, and believed that they were working in utter ignorance of actual conditions as well as with a disposition to meddle where they had no legal or moral right to interfere. He even went so far as to write, toward the very close of the struggle, that he considered "the relation of master and slave, controlled by humane laws and influenced by Christianity and an enlightened public sentiment, as the best that can exist between the white and black races while intermingled as at present in this country.”

This passage does not appear in the Southern biographies of Lee, and it can be justly interpreted only as a partial utterance in view of a most complicated and difficult problem. For that Lee himself disliked slavery there can be no possible doubt. The few slaves that ever belonged to him personally he set free long before the war, and he took time in the very thick of his military duties to arrange at the appointed date for the manumission of those who had been left to his wife by her father.

The letter as to the benefits of the relation between master and slave was written to urge gradual abolition as a reward for faithful military service, and some remarks attributed to Lee after the war form the best possible comment on his pro-slavery utterance, especially in view of all that has come and gone in the last forty years.

"The best men of the South have long desired to do away with the institution and were quite willing to see it abolished. But with them in relation to this subject the question has ever been: what will you do with the freed people? That is the serious question today. Unless some humane course, based upon wisdom and Christian principles, is adopted, you do them a great injustice in setting them free.”

Yet, after all, in fighting for the Confederacy, Lee was fighting for slavery, and he must have known perfectly well that if the South triumphed and got free, slavery would grow and flourish for another century at least. It is precisely this network of moral conditions that makes his heroic struggle so pathetic, so appealing, so irresistibly human.

Before the war, also, he expressed himself on the general subject in the most explicit way. “In this enlightened age there are few, I believe, but will acknowledge that slavery, as an institution, is a moral and political evil in any country.”

An Englishman, Herbert C. Saunders, reporting a conversation with Lee in 1866, says: “On the subject of slavery he assured me that he had always been in favor of the emancipation of the negroes, and that in Virginia the feeling had Men strongly inclining in the same direction, till the ill-judged enthusiasm (amounting to rancour) of the abolitionists of the North had turned the Southern tide of feeling in the other direction. He went on to say that there was scarcely a Virginian now who was not glad that the subject had been definitely settled, though nearly all regretted that they had not been wise enough to do it themselves the first year of the war."

In giving his son advice, in 1868, with regard to the employment of laborers, General Lee writes: “You will never prosper with the blacks, and it is abhorrent to a reflecting mind to be supporting and cherishing those who are plotting and working for your injury, and all of whose sympathies and associations are antagonistic to yours. I wish them no evil in the world—on the contrary will do them every good in my power, and know that they are misled by those to whom they have given their confidence; but our material, social, and political interests are naturally with the whites."

In a conversation with Colonel Thomas H. Carter immediately after the close of the war, General Lee said: “I have always observed that wherever you find the negro, everything is going down around him, and wherever you find the White man, you see everything around him improving."

He was devoted to animals, and children disarmed his formality. Standing one day with officers of his staff in the yard of a house on a hill, the enemy located them and directed a hot fire on them. Suggesting that the others take refuge elsewhere, he remained where he was. Watching him, they saw him pick up a young bird, carry it across the yard and put it safely on the limb of a tree.

One of Lee's outstanding traits was his piety. His principle as a soldier, in this respect, is revealed in a letter he wrote in 1856: "We are all in the hands of a Kind God who will do for us what is best, and more than we deserve, and we have only to endeavor to deserve more, and to do our duty to Him, and to ourselves. May we all deserve His mercy, His care, His protection."

By his achievements he won a high place amongst the great generals of history. Though hampered by lack of materials and by political necessities, his strategy was daring always, and he never hesitated to take the gravest risks. On the field of battle he was as energetic in attack as he was constant in defense, and his personal influence over the men whom he led was extraordinary. No student of the American Civil War can fail to notice how the influence of Lee dominated the course of the struggle, and his surpassing ability was never more conspicuously shown than in the last hopeless stages of the contest.

The personal history of Lee is lost in the history of the great crisis of America's national life; friends and foes alike acknowledged the purity of his motives, the virtues of his private life, his earnest Christianity and the loyalty with which he accepted the ruin of his party.

Lee monuments went up in the 1920s just as the Ku Klux Klan was experiencing a resurgence and new Jim Crow segregation laws were adopted. Frederick Douglass complained bitterly that he could scarcely find a northern newspaper “that is not filled with nauseating flatteries of the late Robert E. Lee,” whose military accomplishments in the name of a “bad cause” seemed somehow to entitle him “to the highest place in heaven.”

Theodore Roosevelt, with characteristic restraint, pronounced Lee “the very greatest of all the great captains that the English-speaking peoples have brought forth” and declared that his dignified acceptance of defeat helped “build the wonderful and mighty triumph of our national life, in which all his countrymen, north and south, share.” A generation later, as readers devoured Douglas Southall Freeman’s adoring four-volume biography of Lee, another President Roosevelt would simply laud him “as one of our greatest American Christians and one of our greatest American gentlemen.”

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|