Tajikistan - Corruption

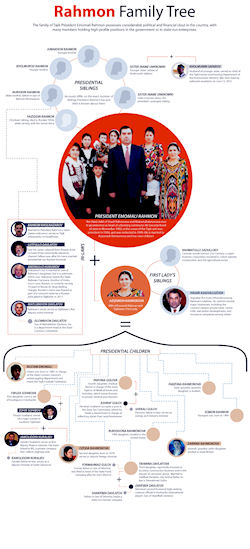

The greatest obstacle to improving the economy is resistance to reform. From President Rahmon down to the policeman on the street, government is characterized by cronyism and corruption. Rahmon and his family control the country's major businesses, including the largest bank, and they play hardball to protect their business interests, no matter the cost to the economy writ large. President Rahmon prefers to control 90% of a ten-dollar pie rather than 30% of a hundred-dollar pie. Rahmon has headed Tajikistan since 1992. His family is widely believed to control virtually the entire economy of the country [which is not saying much, given the poverty of the country].

Tajikistan's business advocates and civil leaders cite corruption and the lack of coherent laws and policies as the greatest impediments to business or reforming social institutions. in Tajikistan success or progress depended on personal relationships with influential officials, rather than institutions and a reliable regulatory framework. Without rule of law, corrupt or ignorant mid-level officials had too much latitude to interfere. The most successful international investors were the Chinese, Russians or Kazakhstanis, who knew how to "move through the gaps," that is, had the cash to pay off the right people. The culture of corruption works both ways - government officials, who clearly don't understand that a rule-based world exists outside their experience, tried to bribe representatives of rating organizations Moody's and Standard and Poor's to get a higher rating.

In 2007 Tajikistan's National Bank admitted it had hidden a billion dollars in loans and guarantees to politically-connected cotton investors (of which $600 million was never repaid), violating its IMF program. The IMF demanded early repayment of some debt, an audit of the National Bank, and other reforms before renewing assistance. In May 2009 the IMF voted to lend a further $116 million to Tajikistan to help it through the next three years; the U.S. was the only IMF member to vote against this, which infuriated the Tajik government. A team from Washington went to Dushanbe to assess government progress, establish new benchmarks for the next tranche of funds, and assess the impact of Roghun fundraising.

Tajikistan ranked very low on the 2012 Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index. It scored 22 out of 100 on the index, placing it 157 on a list of 176 countries. Anemic anti-corruption efforts from the Tajik government have proven ineffective Ė indeed, some anti-corruption units are ironically known to be particularly corrupt. Extremely low official salaries do not help since they force many officials to look for alternative means to make ends meet. Buying a government position is common, and people frequently bribe superiors for promotions. Cultural expectations play a role as well: people are expected to share their good fortune with superiors and extended family, and nepotism or other favors for clan members, extended family, or superiors are commonplace.

Police corruption and brutality are widespread; police have been implicated in many instances of human rights violations and involvement with criminal groups. Many traffic police retained fines they collected for violations. Traffic police posted at regular intervals along roads arbitrarily stopped drivers to ask for bribes. The problem was systemic in part due to the low official wages paid to traffic police. According to reports many traffic police must pay for their jobs, an expense they try to recoup by extracting bribes from motorists.

Police corruption and brutality are widespread; police have been implicated in many instances of human rights violations and involvement with criminal groups. Many traffic police retained fines they collected for violations. Traffic police posted at regular intervals along roads arbitrarily stopped drivers to ask for bribes. The problem was systemic in part due to the low official wages paid to traffic police. According to reports many traffic police must pay for their jobs, an expense they try to recoup by extracting bribes from motorists.

Endemic corruption stifles business by local and international investors. Officials at any number of agencies expect payoffs for opening and running a business. Although a signatory to the OECD Convention on Combating Bribery and the United Nations Convention against Corruption, corrupt practices are deeply embedded in every aspect of commerce, and calculating the actual cost is difficult. The Agency to Fight Corruption and Economic Crimes, which reports directly to the Presidential Administration, has yet to achieve anything significant. Indeed it appears unwilling to take on major corruption cases, which are often linked to high-ranking government officials.

Bribery is endemic. Many businesses view paying off predatory regulators and other officials as a necessary cost of doing business. Legitimate prosecutions for corruption, including bribery, are rare to nonexistent. Ironically, since bribery is so widespread, it proves to be a reliable charge officials can use to silence a potential critic or business rival. Officials tend to face consequences for corruption only when their activity competes with that of more powerful officials.

Due to its crumbling and corrupt education system, Tajikistanís labor force is becoming less skilled and is ill-equipped to provide Western standards of customer service and management. International businesses and NGOs lament the small pool of qualified staff for their organizations. Corruption in secondary schools and universities means degrees do not accurately reflect the level of professional training or competency. Although education is compulsory, many students must work to support their families. Since there few well-paid jobs available, many Tajiks with advanced skills emigrate to find better opportunities.

Nepotism and corruption play a large role in the labor market. Many of the higher prestige or more lucrative jobs require a "buy-in" and continuing payments to supervisors, leading the job holder to look for ways to pay back that sum by seeking bribes or other corrupt activity.

Nepotism and corruption play a large role in the labor market. Many of the higher prestige or more lucrative jobs require a "buy-in" and continuing payments to supervisors, leading the job holder to look for ways to pay back that sum by seeking bribes or other corrupt activity.

Tajikistan is a major transit route for Afghan heroin going to Russia and Europe. According to UN Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC) estimates, 40 tons of Afghan opiates enter Russia each year via Tajikistan. Less than 5% is seized before reaching Russia. Capabilities of Tajik law enforcement agencies are severely limited. Corruption is a major problem. Law enforcement agencies are reluctant to target well-connected traffickers, but are effective against low- and mid-level traffickers. The Drug Control Agency (DCA) is a ten-year-old, 400-officer agency developed through a UNODC project. Many countries are donors, but an INL-funded salary supplement program provides the primary funding. DCA's liaison officers in Taloquan in northern Afghanistan were key to seizures totaling over 100 kilos of heroin in the last four months. U.S Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) agents work with DCA to deepen operations.

The government wants to encourage business development, but faces major obstacles, including its own poor management, cronyism, and corrupt practices. In principle, private entities may establish and own businesses and engage in almost all forms of remunerative activity. Foreign entities may establish, acquire, and dispose of interests in business enterprises. In practice, the old Soviet mentality still prevails. Government inspectors often operate on the principle that activities are not permitted unless they are expressly allowed (or unless the inspector is remunerated for adopting a more flexible interpretation), and since laws are often not readily accessible to public nor uniformly applied and interpreted, businesspeople often find Tajikistan frustrating. In some cases, the existence of informal networks of clan-based, interrelated suppliers force would-be investors to "buy in" to the system, hindering competition and sometimes constraining new investors from fully participating.

Cronyism, nepotism, and corruption create a business environment that favors those with connections to government officials. Tajikistan's regulatory system lacks transparency and poses a serious impediment to business operations. Regulators and officials often apply laws arbitrarily and are unable or unwilling to make decisions without a supervisorís permission, leading to lengthy delays. Executive documents -- i.e., presidential decrees, laws, government orders, instructions, ministerial memos, and regulations -- are often inaccessible, leaving businesses and investors in the dark about rules. Each ministry has its own set of normative acts that are not published and may contradict law or the normative acts of other ministries.

Even well-meaning companies inevitably violate some tax legislation, since internal contradictions and draconian rules often make it impossible to abide by all existing requirements. This plays into the hands of corrupt regulators, who can very easily find evidence of violations for which they then demand bribes to ignore. A new national tax code also became law on January 1, 2013, but it remains more confusing and administratively burdensome than experts had hoped. Until Tajikistan successfully tackles such basic problems as corruption, weak rule of law, and unreliable electricity supplies, it will not attract significant growth in foreign direct investment (FDI).

The Anti-Money Laundering and Combating the Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT) assessment of Tajikistan was carried out by the World Bank in 2007. In addition, the mutual evaluation report was adopted by the Eurasian Group (EAG) on combating money laundering and financing of terrorism.28 Tajikistan was rated partially compliant or noncompliant on 44 out of the 40+9 Financial Action Task Force (FATF) Recommendations, noting the absence of an AML/CFT regime and of a strategy to prevent, detect, disrupt, dismantle ML/TF, or to investigate, prosecute and confiscate the proceeds of these crimes. Due to the identified strategic deficiencies, the EAG placed Tajikistan under the enhanced follow-up procedure and, in June 2011, the International Co-operation Review Group (ICRG) included Tajikistan under its targeted review.

In recent years, Tajikistan managed to establish a comprehensive legal and regulatory AML/CFT system and adopted several measures necessary to effectively prevent and repress ML/TF. These included the adoption of the AML/CFT Law, amending the Criminal Code, the Law on Banking and other sectoral laws, bylaws, and guidance. In February 2010, the Financial Monitoring Department of the NBT (the financial intelligence unit) was established. In July 2012, the Tajik Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) became a member of the Egmont Group, meeting the legal and operational requirements related to its status, core functions, data protection, and ability to exchange information with foreign competent authorities. In October 2014, the FATF acknowledged Tajikistanís significant progress in improving its AML/CFT regime and removed Tajikistan from its global AML/CFT compliance process. In November 2014, the EAG also removed Tajikistan from its enhanced follow-up procedure.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|