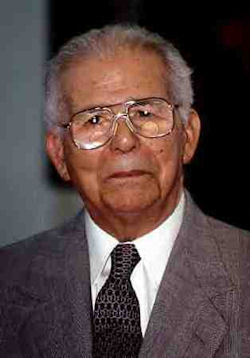

Dominican Republic - Balaguer, Again

Unlike Balaguer, the leaders of the Dominican Revolutionary Party (PRD) promoted a democratic agenda. During the electoral campaign of 1978, the PRD conveyed the image of being the party of change (el partido del cambio); the party pledged to improve the living standards of the less privileged, to include those who felt politically underrepresented, and to modernize state institutions and the rule of law. As a result, the PRD's rise to power generated expectations among the Dominican people for socioeconomic and political reforms that were largely not achieved.

Unlike Balaguer, the leaders of the Dominican Revolutionary Party (PRD) promoted a democratic agenda. During the electoral campaign of 1978, the PRD conveyed the image of being the party of change (el partido del cambio); the party pledged to improve the living standards of the less privileged, to include those who felt politically underrepresented, and to modernize state institutions and the rule of law. As a result, the PRD's rise to power generated expectations among the Dominican people for socioeconomic and political reforms that were largely not achieved.

One threat to democracy that began to recede in 1978 was that of military incursion into politics, given that President Guzman dismissed many of the key generals associated with repression. The armed forces have remained under civilian control. However, this control resulted primarily from the personal relations top military officers had with the president and the divided political loyalties within the officer corps. Even when Balaguer returned to power in 1986, however, the military did not regain the level of importance and influence it had had during his first twelve years in office.

The Guzman administration (1978-82) was viewed as transitional because it faced a Senate controlled by Balaguer's party and growing intraparty rivalry in the PRD, which was led by Salvador Jorge Blanco. Yet, the PRD was able to unify around Jorge Blanco's presidential candidacy (Guzman had pledged not to seek reelection) and defeat Balaguer and Bosch in the May 1982 elections. Tragically, Guzman committed suicide in July 1982, apparently because of depression, isolation, and concerns that Jorge Blanco might pursue corruption charges against family members; vice president Jacobo Majluta Azar completed Guzman's term until the turnover of power in August.

Initial hopes that the Jorge Blanco administration (1982-86) would be a less personalist, more institutional, reformist presidency were not realized. A major problem was the economic crisis that not only limited the resources the government had available and demanded inordinate attention, but also forced the government to institute unpopular policies, sometimes by executive decree. Problems had begun under Guzman: prices sharply increased following the second Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) oil shock, interest rates skyrocketed, and exports declined. In addition, sugar prices fell in 1977-79, rebounded in 1980, and then fell sharply again even as the United States sugar quota was being reduced and as prices of other Dominican exports also declined.

Significant steps toward economic stabilization were taken under the Jorge Blanco administration, although not without difficulty. In April 1984, the government imposed price increases on fuel, food, and other items as part of a package of measures negotiated with the International Monetary Fund (IMF—see Glossary) to renew international credit flows. Protests against these measures escalated into full-scale riots that were tragically mismanaged by the armed forces, leading to scores of deaths and the suspension of the measures.

In the face of growing international constraints, the administration successfully complied with an IMF stand-by program over 1985 and 1986. However, the economic measures induced a sharp recession in the country. Another problem was executive-congressional deadlock, now driven by intraparty factionalism. The PRD was increasingly divided between followers of Salvador Jorge Blanco and Jose Francisco Pena Gomez on the one hand, and Jacobo Majluta Azar, on the other. Other difficulties resulted from the reassertion of patronage and executive largesse.

The situation in the country was perhaps responsible for the outcome of the May 1986 elections: Balaguer emerged victorious with a slim plurality, defeating Majluta of the PRD and Bosch of the PLD; Bosch had nevertheless received 18 percent of the vote, double the percentage from four years earlier. Balaguer had merged his party with several smaller Christian Democratic parties to form the Reformist Social Christian Party (Partido Reformista Social Cristiano—PRSC). However, the promise of a more coherent ideological base for his party was never realized.

Balaguer began his 1986 term by denouncing the mistakes and irregularities carried out by his predecessors. His denunciation led ultimately to the arrest of former president Jorge Blanco on corruption charges. The administration did nothing to remove the factors that fostered corruption, however, seemingly satisfied with discrediting the PRD and particularly Jorge Blanco.

Balaguer also sought to revive the economy quickly, principally by carrying out a number of large-scale public investment projects. He pursued a policy of vigorous monetary expansion, fueling inflationary pressures and eventually forcing the government to move toward a system of exchange controls. Inflation, which had been brought down to around 10 percent in 1986, steadily climbed through Balaguer's first term. Balaguer also faced increasing social unrest in the late 1980s. Numerous strikes, such as a one-day national strike in July 1987, another in March 1988, and another in June 1989, took place between 1987-89; in 1990 Balaguer faced two general strikes in the summer and two others in the fall. Through a patchwork quilt of policies, the administration was able to limp through the May 1990 elections without a formal stabilization plan.

In spite of the country's problems, Balaguer achieved a narrow plurality victory in 1990. In elections marred by irregularities and charges of fraud, the eighty-three-year-old incumbent edged out his eighty-year-old opponent, Bosch, by a mere 24,470 votes. Pena Gomez, the PRD candidate, emerged as a surprisingly strong third candidate.

By 1990 the PRD was irreparably split along lines that had formed during the bitter struggle for the 1986 presidential nomination. Pena Gomez had stepped aside for Jacobo Majluta in 1986 but had vowed not to do so again. The failure of numerous efforts since 1986 to settle internal disputes, as well as extensive legal and political wrangling, eventually left Pena Gomez in control of the PRD apparatus. Majluta ran at the head of a new party and came in a distant fourth.

Once Balaguer was reelected, he focused on resolving growing tensions between his government and business and the international financial community. In August 1990, Balaguer commenced a dialogue with business leaders and signed a Solidarity Pact. In this pact, Balaguer agreed to curtail (but not abandon) his state-led developmentalism in favor of more austerity and market liberalization. He reduced public spending, renegotiated foreign debt, and liberalized the exchange rate, but he did not privatize state enterprises. An agreement with the IMF was reached in 1991, and ultimately what had been historically high rates of inflation in the country (59 percent in 1990 and 54 percent in 1991) receded. Levels of social protest also decreased, as the country looked toward the 1994 elections.

In the 1994 campaign, the main election contenders were Balaguer of the PRSC and Pena Gomez of the PRD, with Bosch of the PLD running a distant third. In spite of suspicion and controversies, hopes ran high that with international help to the Electoral Board, a consensus document signed by the leading parties in place, and international monitoring, the 1994 elections would be fair, ending a long sequence of disputed elections in the Dominican Republic. Much to the surprise of many Dominicans and international observers, irregularities in voter registry lists were detected early on election day, which prevented large numbers of individuals from voting.

In what turned out to be extremely close elections, the disenfranchised appeared disproportionately to be PRD voters, a situation that potentially affected the outcome. The prolonged post-election crisis resulted from the apparent fraud in the 1994 elections. Balaguer had ostensibly defeated Pena Gomez by an even narrower margin than that over Bosch in the 1990 elections. This situation caused strong reactions by numerous groups inside and outside the country: the United States government, the OAS, international observer missions, business groups, some elements of the Roman Catholic Church, and the PRD, among others.

The severe criticism led to the signing of an agreement, known as the Pact for Democracy, reached among the three major parties on August 10, 1994. The agreement reduced Balaguer's presidential term to two years, after which new presidential elections would be held. The agreement also called for the appointment of a new Electoral Board as well as numerous constitutional reforms. The reforms included banning consecutive presidential reelection, separating presidential and congressional-municipal elections by two years, holding a run-off election if no presidential candidate won a majority of the votes, reforming the judicial system, and allowing dual citizenship.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|