Zimbabwe - Currency

In 2009, Zimbabwe abandoned its own worthless currency and began using all major foreign currencies, but mostly the US dollar. The manufacturing sector suffered the deleterious effects of President Robert Mugabe’s policies since 2000. The result has been an increase in the importation of goods, so all foreign currency reserves go towards importing fuel, drugs, raw materials and other commodities that the once-vibrant manufacturing industry can no longer produce.

In 2016 Zimbabwe issued a new currency, known as bond notes, that officially were equal to the US dollar. The government went ahead with the plan on 28 November 2016 despite warnings the new currency will fuel hyperinflation and worsen the already ailing economy. The bond note exacerbated the macroeconomic sustainability. It eroded confidence within the financial system. It created a lot of uncertainties in the market. The central bank announced that the notes would be introduced through formal banking channels in small denominations of 2 and 5 dollars. Individual withdrawal of the notes will be limited to a maximum of 50 dollars per day and 150 dollars per week to curb abuse. The notes are backed by a 200-million-dollar facility from Africa Export-Import Bank.

By early 2017 US dollars and other hard currencies were disappearing. "Bond notes" – the substitute currency that’s accepted nowhere else in the world outside Zimbabwe – are the only thing filling the void.

In 2008 and 2009 the state's central bank printed so much of its currency, the Zimbabwe dollar, that the country experienced mind-boggling hyperinflation that reached 500 billion percent. Immediately before the US dollar was formally adopted in February 2009, $1 could fetch you $35 quadrillion Zimbabwean dollars. That Zimbabwe resorted to the US dollar – the currency of a country with which they have maintained frosty relations for the better part of the past two decades – shows how untenable Zimbabwe’s situation had become, as well as the country’s schizophrenic relationship with money.

Although a multi-currency regime exists in Zimbabwe, the US dollar was still the main currency in Zimbabwe. Notes in small denominations (1, 5 and 10 dollar bills) are handy, as small change is often not available. The following currencies are also included in the multi-currency regime: South African Rand, Botswanan Pula, British Pounds, Euro, Chinese Yuan, Australian Dollar, Indian Rupee and the Japanese Yen. In practice vendors in Zimbabwe rarely accept these currencies.

Government issued 'bond coins' are legitimate tender. Due to fluctuations in the exchange rate, bond coins have replaced rand coins as the commonly used small change. The coins, referred to as “Bond coins” are produced in denominations of 1, 5, 10 and 25 cent values with a fifty cent coin expected to be released into circulation in mid-2015. The coins are supposedly backed by a “Bond” from which they derive their name from – with a US$50 million bond coin facility that the Reserve Bank claim they have arranged for the purpose of providing the coins with intrinsic value.

The country’s commitment to the use of the multicurrency monetary regime, under which the US dollar dominates most transactions, continues to stabilize and restore business confidence in the economy as it removes the exchange-rate risk associated with the use of domestic currencies. By early 2016 Mugabe had agreed to major reforms, such as compensation for evicted white farmers and a big reduction in public sector wages in a bid to woo back international lenders and to have part of its $8 billion in foreign debt cancelled. The authorities have met all quantitative targets and structural benchmarks under the third and final review of the 15-month Staff-Monitored Program (SMP). Moreover, they started to develop a medium term economic transformation program, in line with the broader reform agenda presented at the Lima meetings on arrears clearance in October 2015.

The successful resolution of Zimbabwe’s external payment arrears will be an important step toward normalizing relations with the international financial community and will allow the country to eventually seek a Fund financial arrangement. It will also send strong signals to the international community, reduce the perceived country risk premium, and unlock affordable financing for government and the private sector. This, together with policy reform, will help to achieve sustained economic development through economic transformation, to improve living conditions for the people of Zimbabwe, and to reduce poverty.

Zimbabwe’s level of inflation at its height reached a staggering 231 million percent in 2008, before the government and Reserve Bank stopped tabulating the statistics. When asked by the media if these coins were the first step to re-introducing a new Zimbabwean currency, the Governor reiterated, “We can never be so careless to bring back the local currency,” further stipulating “We have no appetite to do so, and we can’t be careless to do so and we won’t do that.”

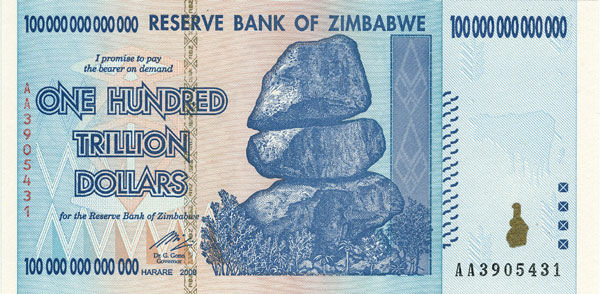

As the Zimbabwean Dollar seemed closer to collapse in 2007, the Reserve Bank resorted to the issuance of “Bearer Cheques” with expiration dates after which the note no longer had value. The Reserve Bank went so far as introducing the world’s largest ever banknote denomination of One Hundred Trillion Dollars in 2008. The Reserve Bank later re-valued the Zimbabwean Dollar the next year by removing 14 zero’s from a new series of banknotes before they finally withdrew the national currency in favor of the US Dollar in an effort to stabilize their faltering and internationally debt-ridden economy.

As of mid-2016 Zimbabwe was experiencing a cash crisis. It was increasingly difficult to withdraw cash at banks and ATMs. There were limits on cash which can be withdrawn from local accounts, with some banks also suspending withdrawals from international accounts and putting restrictions on international Visa and Master Card transactions. Visitors may have difficulty withdrawing cash from ATMs and banks. Travellers cheques and credit/debit cards are not widely accepted.

By mid-November 2016 Zimbabwe’s radio and television stations were flooded with Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe’s jingles promoting the bond notes saying they would be introduced any time this month. The central bank says the bond notes will trade on par with the U.S. dollar and that they will ease the severe cash shortages Zimbabwe has been facing for close to a year now. They are taking US dollars that are valuable and replacing them with bond notes that are just paper, printed paper. And residents are not going to find goods in stores. The money cannot buy because it is not foreign currency. They need foreign currency to purchase things from outside the country.

Zimbabwe Vice President Emmerson Mnangagwa said the government would go ahead with introducing bond notes despite threats of protests. He said bond notes are meant to slow down the smuggling of foreign currency out of Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe’s own local people don’t trust that the government won’t wantonly print more notes than the $200 million Afreximbank loan facility guarantees. They are another currency but very low quality. The bond notes are trading at a discount to the US dollar even before they start circulating.

Most people in the diaspora migrated because they lacked faith in the ability of government to create opportunity and to manage the economy well, after they experienced its failure to do so over decades. Who to blame for the failure, sanctions or corruption, is ofcourse a different issue. There’s no doubt therefore that the Bond Notes announcement spooked those in the diaspora, and they are concerned about the security of the money they send home. The government created the liquidity crisis. By even talking about the bond notes, the government created a bank run.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|