1884-1919 German Togoland

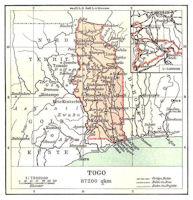

Togoland was a German colony on the Gulf of Guinea, West Africa. It formed part of the territory formerly distinguished as the Slave Coast and was annexed by Germany in 1884. As in the case of South-west Africa, Togoland was handed over to Germany by the British Imperial Government in opposition alike to the opinion of the Gold Coast Colony administration and to the protests of the natives. The area of the colony was some 33,700 sq. m.

Togoland was a German colony on the Gulf of Guinea, West Africa. It formed part of the territory formerly distinguished as the Slave Coast and was annexed by Germany in 1884. As in the case of South-west Africa, Togoland was handed over to Germany by the British Imperial Government in opposition alike to the opinion of the Gold Coast Colony administration and to the protests of the natives. The area of the colony was some 33,700 sq. m.

The population was about 1,000,000. The white inhabitants numbered (1909) 330, of whom 300 were German. In the north the people were mostly Hausa, in the west they belong to the Tshi-speaking clans, while on the coast they were members of the Ewe (Dahomey) tribes. In the coast lands the inhabitants were traders and agriculturists, in the interior they were largely pastoralists. The Hausa were often traders, traversing the country in large caravans. The inhabitants were partly Mahommedans, partly believers in fetish; comparatively few professed Christianity. As a rule the tribes were peaceful. Slave raiding had ceased, but domestic slavery in a mild form continued.

On the coast at Togo German traders established a factory [ie, a trading post]. In 1884 Gustav Nachtigal went to West Africa on behalf of Reichskanzler Bismarck on the gunboat "Möwe". He concluded a protection contract with the representative of King Mlapa of Togo City.

Later, by agreement with local chiefs there were added some 500 square miles of adjacent territory. The hinterland was, or was presumed to be, within the sphere of the Gold Coast administration. At all events the natives, though little interfered with, understood themselves to be under British protection, and that protection was of value, since after the subjugation of the warlike Ashantis who had long terrorised this region of Africa, British authority had brought about a settled peace.

The claims made by Germany to large areas of the hinterland gave rise to considerable negotiation with France and Great Britain, and it was not until 1899 that the frontiers were fixed on all sides. Meantime the development of the coast region had been taken in hand. On the whole the history of the colony has been one of peaceful progress, interrupted now and again by severe droughts.

By 1890 the Togo hinterland, about 80,000 square miles in area, was acknowledged to be a possession of the German Government. To the representations of the Gold Coast Colony Council on behalf of the natives, the reply of the British Imperial Government was that if Germany wished to acquire colonics, her co-operation in the work of civilisation would be welcomed.

Owning their respective lands in common, the native tribal communities had under settled conditions made some progress in agriculture. They grew in rotation each year a crop of yams, and a crop of corn, and on suitable soil, when trade in that commodity had been opened through Lome and the Gold Coast territory, cultivated cotton. By the Germans this new possession was exploited purely for profit. From the lands best adapted for cotton growing the natives were expropriated on a "compensation" fixed by the Germans themselves, and, it was hardly necessary to say, derisive.

In the early 20th century, the German colony of Togo was divided into five "administrative circles" (Lomé-ville, Lomé-circle, Anécho, Misahöhe and Atakpamé with its subdivision of Nuatja) and three "post circles" (Kete Krachi, Sokode with Bassari for subdivision, Sansanné-Mango with its subdivision of Yendi).

Early in the year 1900 the "Kolonial-Wirtschaftliche Komitee" began to devote special attention to extending the cultivation of cotton in the German colonies. The Committee has obtained financial aid from the German Government, and the assistance of scientific men, and instituted experiments on the best methods of cultivation, and also organised a system of encouraging the industry among the natives by purchasing cotton from them and by establishing ginning and baling machinery at suitable centers.

Togo, adjoining the British Gold Coast Colony, was the first locality selected for their operations; here the export of cotton was raised from nothing up to 100 tons in 1904, and the harvest of 1904-1905 was estimated at 250 tons of ginned cotton. A training farm for natives was in operation at Nuatscha.

Under German rule; the Togo became the "model colony" of Germany in Africa and was based on the establishment of plantations and export of food and palm oil. To facilitate this trade, the Germans built three railway lines : the coconut line to Aného, the coffee and cocoa line to Kpalimé , and the cotton line to Blitta (center of the country). All terminals ended in the Lomé wharf, which was built in 1904.

To ensure native labor for these estates the natives were subjected to a poll tax of 6s. per head annually. In order to pay it, and with rare exceptions they had no other means, they were obliged to sell themselves for a part of the year. This made the cultivation of their own farms difficult. To add to the difficulty they were subjected to annual corvees. In large gangs they were transported from one part of the country to another, and, under conditions which caused a high rate of mortality, forced to labor on the making of roads and other works. Almost always these demands coincided with their own seed-time.

Through the resultant losses of their crops they were brought down to a state of abject penury. Since, too, their cotton could now onlv be sold to Germans, it became no uncommon practice for a German official, when the crop was ripe, to come along, inspect it, and "purchase" it for one shilling, or two shillings. But the grievances of the natives were not economic merely. There were the same punishments without inquiry and the same abuse of the lash for infringements of a Code of which the natives remained totally ignorant. And in regard to native women, there was the same disregard of honour and decency. In a word, Togoland became in West Africa an area of misery from which all who could escaped across its boundaries.

With a breadth from west to east of 150 miles on the average, and a length of 500 miles from north to south, Togoland lay like a long wedge between the British Gold Coast territory on the one side and the French possession of Dahomey on the other. On the north it was limitrophic with the French colony of Upper Senegal. The possession was thus readily open to invasion from all sides, and as the Germans dared not trust the natives with arms, and had only a force of some 500 native police, and those not wholly to be relied upon, the resistance they could offer was but feeble. Their power had in fact been undermined by their own methods of government.

The real obstacle to attack lay both in the distances to be covered, and the character of the country, for despite its development by forced labour, roads in the ordinary sense of the word were still few. The only practicable means of traversing it was with a multitude of native porters from three to four times as numerous as the combatant element. Much therefore depended upon the goodwill of the population, and of that the invaders were assured.

Efforts had been made to reconcile the natives to German rule. This process began in the schools, where the children were taught to sing the German national anthem and to wave German flags; the teaching of English formerly common in the mission schools was abandoned. But the emigration of natives to the Gold Coast, which had resulted from the harsh methods of Herr W. Horn (governor 1902-5) and other officials was still marked in 1913, while on the east there was a similar attraction to Dahomey.

Herr Horn had been dismissed for misconduct; his successor, Count J. von Zech, was more conciliatory to the natives and gave much attention to the development of railways and trade. In 1912 Germany made a departure in its colonial appointments by sending out as governor a member of one of the reigning families. The last German Governor of Togo in 1914 was Adolf Friedrich, Herzog von Mecklenburg-Schwerin, a relative of the Russian Czars through Catherine the Great. Mecklenburg, who was known as leader of an expedition which had crossed Africa. The duke had overseen the linking up of Togoland to Germany by submarine cable (Jan. 1913), the extension of agriculture and an expansion of exports.

The Germans were very anxious to keep their footing in this part of Africa. Togoland was looked upon as the nucleus of a much larger possession. Assuming German success in the war, the probabilities were judged to be that the African dependencies of the German Empire would stretch across the Continent from the Atlantic to the Indian Ocean, and from the Mediterranean to the northern boundary of the South African Union. In brief, the Union would become the only non-German part of Africa, and even that an appanage. In 1914 these ambitions were no secret. That Germany aspired to found in Africa a vast consolidated dominion was a project which had reached the stage of public discussion.

The German Tropical Empire was to comprise not only both German and British East Africa, but the Congo Free State and French Equatorial Africa, thus linking East Africa up with the Cameroons. And on the north it was to comprise Uganda and the Soudan, with Egypt and Tripoli, again become nominally Turkish but really German dependencies. There was even in view a German express route from Berlin via the Mediterranean to Timbuctu. On the south the possession was to be linked up with German South-west Africa by the annexation of Portuguese Angola, and Rhodesia as well as Nyassaland, and Portuguese East Africa. The capability of these African territories of supplying raw materials for German industry at a cheap rate had been carefully gone into, and the easiest means of economical control by an apparent alliance for the time being with Mohammedanism in the north schemed out.

A native army of from 60,000 to 80,000 men, trained on European methods, and scientifically equipped, could, it was computed, be maintained without costing the German Imperial Treasury a cent.

Maj. von Döring, the acting governor, had the advantage in the critical days of July 1914 of direct communication with Berlin by a wireless station at Kamina, which had just been erected. He made preparations to invade Dahomey, on the assumption that Great Britain would not enter the war. When this supposition was proved to be wrong Maj. von Döring received instructions from Berlin to propose that Togoland and the adjacent French and British colonies should remain neutral. The offer was made to the local authorities concerned but was rejected, in the case of the British by order of the Colonial secretary in London. The chief concern of Berlin in regard to Togoland was to preserve the use of the Kamina wireless station, through which they could communicate with all the other German colonies in Africa.

A French column, setting out from Abome, crossed the frontier, and meeting with no opposition, had made a swift march across country towards Kamina. Senegalese Tirailleurs from Dahomey under Capt. A. Castaing occupied Little Popo (Anecho) on Aug. 6 and Togo on Aug. 8. And on 26 August 1914 the German troops laid down their arms. The campaign, the shortest in the war, had lasted just three weeks, and German dominion in West Africa was dead.

The conquest of Togoland — a region the size of Ireland — was notable not only for its rapidity and neatness of execution, but for the fact that the operations were conducted entirely by the local authorities and by the troops on the spot when the war began — in this respect the little campaign was unique.

The eastern part of Togo was placed under French mandate by the Treaty of Versailles of 28 June 1919. The western part of German Togoland was placed under a British mandate by the Treaty of Versailles of June 28, 1919. It then became a trust territory of the United Nations, administered with the neighboring colony of the Gold Coast, under the name of Trans-Volta Togo. The two colonies constituted the Republic of Ghana on 6 March 1957.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|