Ship Building 1897-01 - McKinley, William

At the 1896 Republican Convention, in time of depression, the wealthy Cleveland businessman Marcus Alonzo Hanna ensured the nomination of his friend William McKinley as "the advance agent of prosperity." The Democrats, advocating the "free and unlimited coinage of both silver and gold" -- which would have inflated the currency -- nominated William Jennings Bryan. Hanna used large contributions from eastern Republicans frightened by Bryan's views on silver. In the friendly atmosphere of the McKinley Administration, industrial combinations developed at an unprecedented pace. However, McKinley condemned the trusts as "dangerous conspiracies against the public good."

At the 1896 Republican Convention, in time of depression, the wealthy Cleveland businessman Marcus Alonzo Hanna ensured the nomination of his friend William McKinley as "the advance agent of prosperity." The Democrats, advocating the "free and unlimited coinage of both silver and gold" -- which would have inflated the currency -- nominated William Jennings Bryan. Hanna used large contributions from eastern Republicans frightened by Bryan's views on silver. In the friendly atmosphere of the McKinley Administration, industrial combinations developed at an unprecedented pace. However, McKinley condemned the trusts as "dangerous conspiracies against the public good."

Not prosperity, but foreign policy, dominated McKinley's Administration. Upon taking office in 1897, President William McKinley hoped to avoid entanglement in the problems in Cuba so that he could pursue his domestic agenda of continuing the U.S. economy's recovery from the depression. Although some individuals pushed for overseas economic and territorial expansion, they were in the minority and did not reflect the general mood of the country at the beginning of McKinley's term. During the first year of his presidency, most of the American public was content to passively support the cause of Cuban independence. Public opinion in the United States dramatically changed by his second year, influencing the president to reorder his priorities.

Reporting the stalemate between Spanish forces and revolutionaries in Cuba, newspapers screamed that a quarter of the population was dead and the rest suffering acutely. Public indignation brought pressure upon the President for war. Relations between the United States and Spain were rapidly becoming strained in the winter of 1897-8 over the Cuban insurrection. The sympathies of the entire American people were with the Cubans in their struggle for freedom from Spanish domination. Their sympathy was accomplished by material aid, for filibustering expeditions were constantly being fitted out in the United States. Spain accused the United States of conniving at the aid secretly given, and the feeling against Americans in Havana became exceedingly bitter.

Finally in January, 1898, riotous demonstrations against Americans in Havana demanded the presence of a United States warship for their protection. President McKinley sent the battleship Maine from Key West. The Maine was received by the Spanish authorities with all the official courtesies due and the riotous demonstrations in Havana ceased. On the night of Feb. 15, 1898, the Maine was destroyed by an explosion in Havana harbor. The American people in a sudden flame of anger attributed the destruction of the vessel and the death of 386 men of her crew, to Spanish conspirators. Spain herself assumed arrogantly that the Maine was destroyed by the carelessness of her own men. The destruction of the battleship was not the cause of the war between the United States and Spain; but beyond question it hastened it.

Finally in January, 1898, riotous demonstrations against Americans in Havana demanded the presence of a United States warship for their protection. President McKinley sent the battleship Maine from Key West. The Maine was received by the Spanish authorities with all the official courtesies due and the riotous demonstrations in Havana ceased. On the night of Feb. 15, 1898, the Maine was destroyed by an explosion in Havana harbor. The American people in a sudden flame of anger attributed the destruction of the vessel and the death of 386 men of her crew, to Spanish conspirators. Spain herself assumed arrogantly that the Maine was destroyed by the carelessness of her own men. The destruction of the battleship was not the cause of the war between the United States and Spain; but beyond question it hastened it.

Unable to restrain Congress or the American people, McKinley delivered his message of neutral intervention in April 1898. Congress thereupon voted three resolutions tantamount to a declaration of war for the liberation and independence of Cuba. The outbreak of the Spanish War found the navy equipped with 77 vessels, including several coast line battleships such as the Iowa, Indiana and Oregon and the powerful armored cruisers New York and Brooklyn. The war developed the remarkable preparedness of the navy, which practically annihilated that of Spain in a campaign of 110 days. The United States destroyed the Spanish fleet outside Santiago harbor in Cuba, seized Manila in the Philippines, and occupied Puerto Rico.

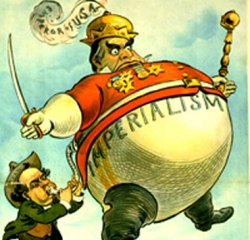

When McKinley was undecided what to do about Spanish possessions other than Cuba, he toured the country and detected an imperialist sentiment. Thus the United States annexed the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico. In 1900, McKinley again campaigned against Bryan. While Bryan inveighed against imperialism, McKinley quietly stood for "the full dinner pail." His second term, which had begun auspiciously, came to a tragic end in September 1901. He was standing in a receiving line at the Buffalo Pan-American Exposition when a deranged anarchist shot him twice. He died eight days later.

To challenge Spain effectively on the issue of Cuba, McKinley needed a strong Navy. The service that the new administration inherited in 1897 was in the midst of sustained growth and reform following twenty years of purposeful neglect. Congress in 1897 added but three torpedo boats and a training ship to the navy.

But in 1898, the naval program was the largest ever authorized at a single session of congress. The list included three firstclass battleships larger than any before designed for the American navy, sixteen torpedo boat destroyers-the first ever built by the United States, twelve torpedo boats, four coast defense monitors and one gunboat. The Spanish-American war undoubtedly was the direct moving cause of this generous expansion of the navy. The war had demonstrated the fact that the United States could not claim immunity from war with a foreign power and that the naval combats of the future were to be fought with firstclass battleships.

The American navy was notoriously weak in battleship strength. Then, too, the early part of the war was filled with constant apprehension of an attack on the Atlantic coast by some of Spain's swift cruisers. The fears were ungrounded, but on paper at least, Spain had at least five armored cruisers, any one of which, effectively handled, might have worked untold disaster to any one of a dozen Atlantic coast cities. It was the remembrance of this fear that impelled congress to authorize the construction of the four coast defense monitors, Arkansas, Florida, Nevada and Wyoming. The necessities of the service during the war had also resulted in a demand for torpedo boat destroyers, and congress provided them.

The additions to the navy authorized by congress in 1898 were made in response to the same sentiment which impelled the notable additions the year after. Three first-class battleships, the West Virginia, Nebraska and Georgia, three great armored cruisers, the California, Pennsylvania and Virginia, and six protected cruisers were provided for.

The country's approval was so marked that congress in 1900 provided for two more firstclass battleships, the New Jersey and Rhode Island, three armored cruisers, the South Dakota, Maryland and Colorado, three protected cruisers of a new and advanced type, the Charleston, Milwaukee and St. Louis, each of 9,700 tons displacement.

Congress in 1900 also made a new departure in naval construction by providing for seven submarine torpedo boats. For several years the Holland submarine boat company had been conducting experiments in submarine navigation and finally had produced a submersible craft which won the approval of the navy department, which had watched the experiments with the closest detail. The experiments proved that a submarine boat could be navigated successfully under water, that the officers and crew could perform their duties with perfect comfort and safety and that torpedoes could be discharged from the submerged craft with reasonable accuracy. The navy department also had kept close watch of similar experiments made by the British and French navies, and waa satisfied that the American type of submarine warship was superior to any which had been developed abroad.

The inventors had perfected many new devices and made so many improvements upon the first plans that in April, 1900, the contract for the original Plunger was cancelled and another contract signed for a new and improved Plunger. By this time the naval authorities were fully convinced of the practicability of the submarine warship and in 1900 congress authorized the construction of seven additional boats - the Adder, Grampus, Holland, Moccasin, Pike, Porpoise and Shark, the sum of $170,000 each being appropriated for the hull and machinery. The navy has adopted the submarine torpedo boat with enthusiasm. Officers and men proved eager for service in them and all boats now in commission are in the hands of men trained in the submarine service. The moral effect of the knowledge that a harbor contains one or more submarine torpedo boats, it was believed, will give more effectual protection against the fleet of an enemy than any number of submarine mines, either contact or floating. An enemy's fleet seemed likely to keep at a safe distance from the coast when it knows that that coast is patrolled by submarine boats, able to cruise for many miles under water and able to detect a hostile fleet long before the officers of the hostile fleet can locate the submarine.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|