Chapter Six The PLA Army's Struggle for Identity

James C. Mulvenon

Before the atrocities of September 11, 2001, ground forces appeared to be the big loser in the current evolutionary phase of modern warfare. The clean, precise style of airpower, combined with the decline of conflicts calling for large land battles, had increased the institutional momentum for air and naval forces at the expense of their ground force counterparts. Similar trends had upended the historic dominance of ground forces in the Chinese military, which had moved over the last 20 years from a focus on massive land battles with the former Soviet Union to littoral defense and power projection from its eastern coast against the dominant planning scenario, Taiwan. While the necessity for homeland defense has possibly generated an additional, powerful institutional rationale for the U.S. Army, Chinese ground forces continue to struggle with issues of identity and mission. Once the unchallenged heart and soul of the People's Liberation Army (PLA), Chinese ground forces remain the dominant service in the military in terms of manpower, resources, doctrine, and prestige. The other services, however, are clearly in the ascendance, while the ground forces have been in a long, slow decline.1 This chapter examines the evolution of Chinese ground forces from their guerrilla origins through their period of preeminence to the difficult challenges of the current era. Current trends are examined, including changes in the roles and missions of the force, as well as its strategy and doctrine, organizational structure, equipment, and training. The essay concludes with some speculation about future trajectories for the ground forces.2

Evolution of China's Ground ForcesLong before the People's Republic of China (PRC) fielded significant numbers of naval, air, or strategic rocket forces, there was the Red Army, a ragtag collection of foot soldiers schooled in the tenets of Maoist guerrilla struggle. Only after this revolutionary vanguard defeated the modern militaries of the Empire of Japan and the Kuomintang did the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership seriously consider forming the other elements of a modern military. Even so, the wars of the first 30 years of the PRC were predominantly land wars, fought by foot soldiers in Korea, India, and Vietnam. Among the many continuities of the era stretching from the 1920s to the late 1970s was the doctrine of People's War, which was centered on the ground forces and their continental orientation. The strategy implicitly assumed that China's nascent power projection forces, including littoral naval and frontline air assets, would act as little more than a speed bump for an invading high-tech enemy, which was defined as the United States from 1949 to the mid-1960s and the Soviet Union from the mid-1960s to the mid-1980s. The real battle would be fought from an inner defense line, staffed with a mixture of main-line ground forces and local militia. The ground forces themselves were organized by infantry corps, called field armies, which generally had three infantry divisions and smaller support units. These units were attributed with a light infantry operations capability, along with some combined arms assistance, with militia units providing combat and logistical support for "luring deep."3 The late 1970s and early 1980s were a transitional period for the ground forces, defined by the seemingly contradictory slogan of "People's War Under Modern Conditions."4 This strategy called for the armed forces to defend China closer to its borders, fighting the Soviets "in a more mobile style of war with combined arms and joint force."5 As Dennis Blasko has outlined, the emphasis in the ground forces shifted to "more tanks, self-propelled artillery, and armored personnel carriers, which added mobility and also offered the possibility of protection from Soviet NBC (nuclear, biological, chemical) attacks."6 The majority of group armies were deployed in garrison locations along expected avenues of attack from the former Soviet Union and Mongolia. Nearly one-half of the group armies were located to protect Beijing and Manchuria from a Soviet attack, while two group armies in the Lanzhou military region were tasked with fighting the Soviet Red Army as it crossed the desert. The necessary modernization to achieve these goals was never completed during this short-lived period because the costs were judged to be prohibitive. In the mid-1980s, Deng Xiaoping began to redefine PLA orientation radically, beginning with a reassessment in 1985 of the overall international security environment that lowered the probability of a major or nuclear war. Instead, Deng asserted that China would be confronted with limited, local wars on its periphery. The natural consequence of this sweeping reassessment was an equally comprehensive reorientation of the Chinese military. The number of military regions was reduced from 11 to 7, and the 37 field armies were restructured to bring "tank, artillery, anti-aircraft artillery, engineer, and NBC defense units under a combined arms, corps-level headquarters called the Group Army."7 Between 1985 and 1988, the 37 field armies were reduced to 24 group armies, and thousands of units at the regimental level and above were disbanded.8 Overall, the PLA was reported to have cut more than one million personnel from the ranks, though Yitzhak Shichor has thoroughly dissected the many empirical problems associated with these announcements.9 The period between 1985 and the present has been marked by restructuring, reform, doctrinal experimentation, and implementation. The ground forces have witnessed few real tests since these changes took effect, with the exception of operations in 1987 on the Vietnam border. Ironically, the largest mobilization of ground forces took place during the 1989 Tiananmen crisis, when the combat skills of the troops were practiced on lightly armed or unarmed civilians in the streets of the capital. Since then, however, the focus of the entire military has shifted to a single, dominant planning scenario: Taiwan. While many elements of the PLA welcomed the emergence of the Taiwan scenario as a tangible justification for increased budgets and procurement, the ground forces likely view this situation with mixed emotions, since the 100 miles of water separating Taiwan from the mainland offer little direct role for the Army. Instead, the scenario is dominated by the newly ascendant naval and air forces, with the ground forces pushed to the rear in support. The next section explores the contours of this new reality for the army.

Current Trends in the Ground Forces

Roles and MissionsIn outlining the roles and missions of the Chinese ground forces, official sources provide general, aggregated, and thus ultimately unsatisfying definitions. According to the 1997 National Defense Law: The active units of the Chinese People's Liberation Army are a standing army, which is mainly charged with the defensive fighting mission. The standing army, when necessary, may assist in maintaining public order in accordance with the law. Reserve units shall take training according to regulations in peacetime, may assist in maintaining public order according to the law when necessary, and shall change to active units in wartime according to mobilization orders issued by the state. Under the leadership and command of the State Council and the Central Military Commission, the Chinese People's Armed Police force is charged by the state with the mission of safeguarding security and maintaining public order. Under the command of military organs, militia units shall perform combat-readiness duty, carry out defensive fighting tasks, and assist in maintaining the public order.10 To understand the true role of the ground forces at a higher level of detail, it is necessary to step back from discussions of particular scenarios and instead derive the missions from China's national military objectives. David Finkelstein has done the work for us, identifying China's three national military objectives:

The ground forces have a role to play in each of these objectives. More than any other service, the ground forces and related paramilitary units (such as the People's Armed Police [PAP]) are the front line in defending the party from both internal and external enemies, and thus safeguarding stability. As for the second objective, sovereignty and aggression are complicated concepts for the Chinese, as they can be both offensive and defensive in nature. For example, the ground forces clearly have a central role in defending the sovereignty of the continental landmass from external aggression, though active defense demands that naval and air forces initiate contact with the aggressor away from China's shores. At the same time, however, the Chinese definition of defending sovereignty also includes assertion of sovereignty over Taiwan, which falls disproportionately on the backs of China's power projection forces in the People's Liberation Army-Navy (PLAN) and the People's Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF). Given that Taiwan is the core-planning scenario for a military operating with growing but still finite resources, the bulk of funds for modernization is therefore allocated to non-ground force units in the navy, air force, and strategic rocket forces. Within these guidelines, the main roles and missions of the ground forces primarily involve continental defense and internal security. As for continental defense, Blasko et al., capture the current dynamic succinctly: The PLA faces no immediate land threat to the integrity of the Chinese landmass. Even if such a threat existed, the PLA's current size, structure, deployment, level of training, equipment and doctrine of a "people's war" is probably sufficient to deter an attacker from an invasion because of the casualties the existing force could inflict on the invader.12 Moreover, as the PLA shifts its doctrine to deal with local wars on the periphery of China, the navy and air force have risen in importance, receiving priority in PLA modernization efforts and naturally growing larger in proportion to the total force. In terms of internal security, Blasko writes, "the primary mission of the active duty force is external defense, while the PAP is tasked with internal or domestic security. As a secondary mission, the active duty and reserve PLA forces and militia may assist the PAP in maintaining domestic security."13

DoctrineChina's primary military doctrine is defined by the phrase active defense (jijifangyu).14 While this forward-leaning doctrine relies heavily on littoral naval and air assets, the ground forces still have important roles to play. Specifically, they are expected to "conduct joint and combined arms operations of a limited duration along the periphery of China using existing weapons."15 These forces are expected to suffer attrition from enemy air forces and other long-range strike assets and then wage mobile, positional warfare against invading forces. In this scenario, rapid reaction forces would serve as the core of the ground forces response, with mobile units likely flowing into the theater of operations from adjacent military regions. Given the low probability that an enemy would make the same mistake as the Japanese in the 1930s and deploy ground troops to the Chinese landmass, however, the ground force role in active defense has been limited to exercises with existing equipment and has not enjoyed the same high procurement priority as advanced fighter aircraft or submarines. Moreover, ground forces do not play a large role in the active revolution in military affairs debate within the PLA, further sidelining the army's influence over the future trajectory of PLA concept development and doctrinal evolution.

Organizational StructureThe traditional structure was divided into three rough categories: main force units, local or regional forces, and militia units. Prior to 1985, the main force units were corps, also known as field armies. After 1985, the main force unit was the group army, composed of approximately 60,000 troops divided into 3 infantry divisions, a tank division or brigade, an artillery division or brigade, an antiaircraft artillery division or brigade, a communications regiment, an engineer regiment, and a reconnaissance battalion. Beneath the group army, the ground forces are further divided into several levels of deployment:

The specific configuration of individual group armies is often dictated by geographic location. Different military regions (MRs) face strikingly different scenarios, and thus group armies display combinations of units and equipment appropriate to their unique area of responsibility. Among the ground force-heavy regions, the Lanzhou, Beijing, and Shenyang MRs are configured for land threats from the north, while the Lanzhou MR is also equipped for suppression of separatist activity in Tibet and Xinjiang. Similarly, the Shenyang MR is prepared for Korea contingencies. The Chengdu and Lanzhou MRs are also for Indian scenarios, and the Chengdu and Guangzhou MRs are arrayed for Southeast Asian threats. Among the least ground force-oriented are the Jinan MR, which is directed toward blunting maritime threats from the Sea of Japan and the Nanjing MR, which is focused on Taiwan. Other important organizational trends include significant downsizing, the emergence of brigades and rapid reaction units, modernization of the command, control, communications, computers, and intelligence (C4I) infrastructure, the rise of a noncommissioned officer corps, and the divestiture of ground force unit business enterprises.

DownsizingIn 1978, Deng Xiaoping and the reformers inherited a military ill suited to the needs of modern warfare. In a 1975 speech, Deng summed up his feelings about the state of the PLA, describing the army as suffering from "bloating, listlessness, arrogance, extravagance, and laziness [zhong, san, jiao, she, duo]."16 One of the first items on the agenda was a reduction in personnel. From 1985 to 1988, more than one million personnel were reportedly trimmed from the ranks, though Shichor's analysis brings into question many of the numerical assertions by official Chinese sources. In particular, he points out that "it is unclear whether the cut of one million military personnel announced in 1985 includes or excludes the more than half a million troops collectively demobilized since 1982."17 At the 15th Party Congress meeting in September 1997, Jiang Zemin announced an additional cut of 500,000 personnel over 3 years. Among the service branches, the ground forces suffered disproportionately, reflecting the ascendancy of the air and naval branches. Blasko writes: According to the July 1998 Defense White Paper, ground forces will be reduced by 19%, naval forces by 11.6%, and air force personnel by 11%.18 These percentages amount to a reduction of about 418,000 ground forces, 31,000 naval personnel, and 52,000 air force personnel.19 Of the 500,000 personnel to be reduced, the ground forces will account for nearly 84% of the total. An important implication of the 500,000 man reduction under way is that the percentage of PLA ground forces within the total force structure will decrease as the percentages of naval and air forces increase.20 At the same time, however, the ground forces after the cuts still comprised 73 percent of the total force structure, with the navy and air force only about 10 percent and 17 percent, respectively. Thus, it is important to contextualize the downsizing trends by noting that the PLA is likely to remain dominated by ground forces for several more decades.21 The downsizing in the ground forces had direct consequences for the organization of units. Three group armies (the 28th in Beijing MR, 67th in Jinan MR, and 64th in Shenyang MR) were reportedly disbanded, and many if not all of the remaining group armies were slated to lose a full division through "deactivation, resubordination, or downsizing."22 Several divisions were demobilized, 14 were reassigned to the People's Armed Police, a few were transferred from one group army to another, one was transformed into the second PLAN marine unit, and several were downsized to brigade level.23 Subordinate elements of demobilized headquarters and units were transferred to other ground forces headquarters. Some of the PLA units in the 1997-2000 downsizing were transferred to the People's Armed Police.24 Currently, PAP strength is approximately 800,00025 but is probably on its way to about one million as the PLA continues its reduction through the year 2000.26 In addition, the PLA created a system of reserves.27 An April 1998 expanded meeting of the Central Military Commission emphasized the need to expand the reserve forces. After the meeting, the military districts were ordered to step up the implementation of plans to build reserve units.28 Equipment not needed in the PAP could be retired, put in storage, or transferred to the reserves or militia.

Rapid Reaction UnitsFrom the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s, the most important organizational reform for the ground forces was the creation of rapid reaction units (RRUs). Their mission is to be "the first PLA forces to respond in time of crisis," ready to mobilize in 24 to 48 hours.29 In addition to the 15th airborne group army, which is an air force unit, the PLA has designated four group armies (the 38th, 39th, 54th, and 23rd) as RRUs.30 Within each military region, one or more divisions has been designated as an RRU and equipped partially with new equipment. These units were expected to deploy either within their military regions or nationwide.31 They received priority in training and participated in doctrinal experiments.32 Eventually, RRUs were projected to include 10 to 25 percent of the entire force. In June 2000, the Department of Defense (DOD) reported that "approximately 14 of [PLA ground force] divisions are designated 'rapid reaction' units: combined arms units capable of deploying by road or rail within China without significant train-up or reserve augmentation."33 At the same time, RRUs have reportedly created new sets of problems related to force coordination, logistics support, and command, control, communications, and intelligence (C3I).34

BrigadesWith the relative decline of interest in rapid reaction units, attention has shifted to the development of brigades (lu). Commanded by a senior colonel, these units are composed of several battalions, but with significantly smaller combat service support units than divisions.35 Overall, brigades are manned with approximately one-third to one-half the strength of a division of the same arm. Regiments will serve as intermediate headquarters between brigade and battalion level for independent brigades. Brigades are intended to make PLA combat units "more rapidly deployable and flexible."36 According to a 2000 DOD report, "China's ground forces are comprised of 40 maneuver divisions and approximately 40 maneuver brigades."37

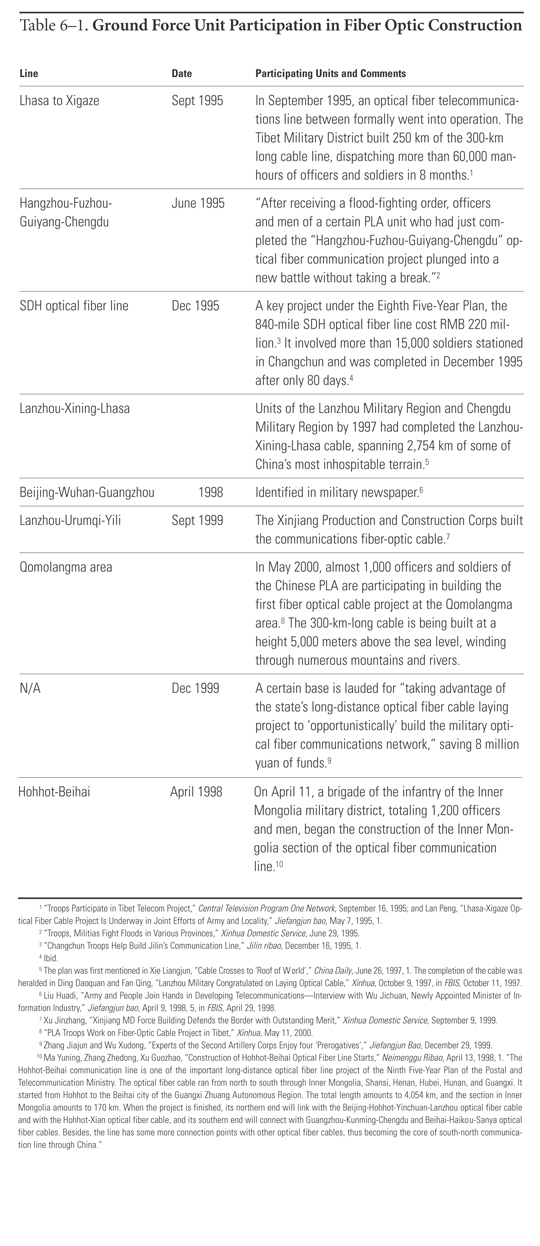

C4I ModernizationPLA ground forces have long suffered from an inadequate communications infrastructure, characterized by outdated technology, limited capacity, and lack of secure communications. In the past, these weaknesses have severely limited the army's ability to transmit and process large amounts of information or coordinate activities between regions or units, thereby reducing military effectiveness. To overcome these deficits, the PLA has embarked on a well-financed effort to modernize its C4I infrastructure, resulting in a dramatic improvement of transmission capacity, as well as communications and operational security. For their part, the ground forces have contributed significant labor to the construction of this infrastructure, and many ground forces units serve as key nodes of the networks. Open sources also reveal information about specific pieces of C4I infrastructure, most if not all of which would directly benefit the ground forces. A vague article from Xinhua describes the PLA communications system as comprising underground networks of fiber optic cables, communications satellites, microwave links, shortwave radio stations, and automated command and control networks.38 A series of articles in Liberation Army Daily between 1995 and 1997 is more specific, describing the C4I system as being composed of at least four major networks: a military telephone network, a confidential telephone network (alternatively described as "encrypted"39), an all-army data communications network (also known as the all-army data exchange network or all-army public exchange network40), and a "comprehensive communication system for field operations."41 A third account merges the two accounts, arguing that the PLA underground networks of optical fiber cables, communications satellites in the sky, and microwave and shortwave communications facilities in between form the infrastructure for a military telephone network, a secure telephone network, an all-army data communications network, and the integrated field communications network. Specific details about three of the four networks are scarce. A 1995 article in Liberation Army Daily asserts that the army data network, which was begun in 1987, "is responsible for the all-army automatic transmission and exchange of military information in data, pictures, charts, and writing."42 The PLA signal corps has trained over 1,000 technicians so far, it is claimed, to operate and maintain this system, which covers "all units stationed in medium and large cities across China and along the coast."43 One important development for the PLA communications infrastructure has been the laying of fiber optic lines. From an information security perspective, the advantages of fiber optic cables are that they can carry considerably more communications traffic than older technologies, transmit it faster (rates of 565 megabytes per second and higher), are less prone to corrosion and electromagnetic interference, and are lightweight and small enough for mobile battlefield command as well as fixed military headquarters, while at the same time offering much higher levels of operational security. A recent article in the Wall Street Journal highlights many of the difficulties that fiber cables pose for the National Security Agency global signals intelligence effort. Indeed, in the 1980s, some U.S. Government agencies were opposed to the sale of fiber optic technologies to the Soviet Union and other countries, including China, for this very reason. PLA interest in fiber optic cables began in 1993, when the former Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications and the General Staff Department Communications Department agreed to cooperate in constructing 100,000 kilometers of fiber optic cable to form the core of China's long-distance, fiber optic transmission networks and trunk lines.44 By 1995, the two organizations had jointly constructed 15,000 kilometers of fiber, spanning 19 provinces and municipalities. From 1993 to 1998, more than 1 million officers and men, mainly from the ground forces, worked on these key national optical fiber telecommunications lines. In 1999, an official source asserted that the PLA and PAP participated in the construction of more than 10 large optical fiber communication projects.45 The military reportedly receives a percentage of the fibers in any given trunk for its own use, making disaggregation of military and civilian communications much more difficult, and the army units stationed along the lines have connected themselves to the backbone. In terms of specific civilian backbone networks, table 6-1 is a partial list of PLA participation in military-civilian fiber optic cable construction. In addition, the PLA is building its own set of dedicated fiber optic lines, under a program known as the 975 Communications Trunk Line Project.46 These networks reportedly connect the central military leadership in Beijing with ground force units down to the garrison level.47 As a result of the efforts outlined above, PLA C4I capabilities have reportedly increased substantially. According to a 1997 article, more than 85 percent of key armed force units and more than 65 percent of coastal and border units had upgraded their communications equipment. The same article also offered an early assessment of the operational consequences of these changes: The use of advanced optical fiber communications facilities, satellites, long-distance automated switches, and computer-controlled telephone systems has significantly accelerated the Chinese armed forces' digitization process and the rapid transmission and processing of military information. The speedy development of strategic communications networks has shortened the distance between command headquarters and grass-roots units, and between inland areas and border and coastal areas. Currently the armed forces' networks for data exchange have already linked up units garrisoned in all medium-sized and large cities in the country as well as in border and coastal areas. As a result of the automated exchange and transmission of data, graphics and pictures within the armed forces, military information can now be shared by all military units.48 The available open sources consistently forecast continuity in PLA C4I modernization. In other words, the PLA will continue to build an infrastructure that is increasingly digitized, automated, encrypted, faster, more secure, and broadband.

Personnel Changes: Noncommissioned Officer CorpsHistorically, the ground forces lacked a dedicated noncommissioned officer (NCO) corps. In the 1990s, the PLA began experimenting with the creation of NCOs. According to Blasko, the stated purpose of this move was "to attract higher quality soldiers and to increase the proportion of NCOs to conscripts by making voluntary extensions moreattractive."49 Specifically, the PLA sought to cut the number of conscripts from 82 percent of its total force to less than 65 percent by 2000.50 Since then, a system of ranks has been developed for these volunteers who remain in service beyond their period of obligatory service. Training courses for NCOs at military academies have been established. However, most NCOs in the system by 1995 were still not in leadership positions, but instead were specialists and technicians.51 In early 1999, however, the terms of service for conscripts was cut from 3 years (army) and 4 years (PLAN and PLAAF) to 2 years for all services. This placed additional burdens on the NCO corps, which must now shoulder a greater leadership burden in teaching basic soldiering skills and leading recruits through the training cycle.

EquipmentIn 1982, Harlan Jencks asserted, "it seems clear that Beijing does not intend to refit the entire PLA with modern weapons and equipment. The majority of the PLA's 100-plus ground force divisions will remain low- to medium-tech forces."52 Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Beijing selectively equipped only a portion of the ground forces with new weapons, while leaving the remainder to make do with existing equipment. By contrast, the air force, navy, and strategic rocket forces during this period were clearly singled out for priority in equipment modernization. Given the failures of the defense-industrial base to produce indigenously the necessary advanced systems, these services were even permitted to procure small quantities of platforms from foreign suppliers, in particular the Russians. For the ground forces, however, only limited amounts of foreign weapons and equipment (for example, BMP-3s and helicopters) have been introduced into the forces, and the indigenous Chinese defense industry, despite its many failings, continues to be designated as the source of the majority of modern ground force weapons.53 The lack of new equipment has forced the ground forces to modify operations and tactics, especially against a high-tech opponent. In the absence of new systems, the ground forces were instead instructed to "look for ways in which existing equipment can defeat high-technology weapons, while providing advanced weapons to select units."54 Also, ground force units were told to hide existing inventory with better camouflage, concealment, and deception. Despite these efforts, however, Blasko is correct when he argues that the vast majority of existing weapons in the PLA inventory, even when their capabilities are maximized by equipment modification or employment techniques, simply do not have the range to be used in an offensive manner against many modern high technology weapons systems with long-range target acquisition, stand-off, and precision strike capabilities.55 In spite of these problems, however, the strategy of gradually equipping the ground forces continues to make sense. There will never be enough budgetary largesse to equip such a large army fully, nor does the leadership desire to elevate even the majority of the ground forces to advanced status. The current military environment, which is focused on littoral warfare, does not justify such a huge expense. Moreover, the bulk of ground forces personnel are not prepared for the introduction of modern equipment, either in terms of education level or comfort with advanced technology. Jiang Zemin directly addressed this point when he said, "we should let qualified personnel wait for the arrival of equipment rather than let equipment wait for qualified personnel to operate it."56 For the foreseeable future, therefore, the ground forces will modernize at a slow pace, equipping select units with new systems while allowing the bulk of the force to fade into obsolescence.

TrainingThe ground forces currently train at three levels: individual skills, basic units, and combined arms regiments and divisions. RRUs receive priority in training.57 The PLA has increased the number of joint and combined arms exercises (by definition large-scale exercises conducted at division or higher levels) since 1990,58 as well as night operations, opposing forces training, and live fire exercises.59 Many of these exercises could be described as deliberately "experimental."60 After a specific unit conducts an exercise, the lessons learned are analyzed, codified, and eventually promulgated.61 Changes in conscription have affected training. Until the late 1990s, the ground forces were hampered by the limitations of the conscription. Blasko et al., outline the problem: Because of its annual conscription and demobilization cycle (both of which take place in the late autumn) and method of providing basic training at the unit level (division or below during December and the first months of the calendar year), the PLA is confronted with a situation in which one-quarter to one-third of the troops in its units are always first-year soldiers. As such, small unit leaders must spend large blocks of a training year on basic, individual soldier tasks. Until they master these tasks, soldiers can only partially contribute to and learn from larger collective or unit training. Although officers remain in their basic units for many years, the turbulence resulting from enlisted rotations implies that every time a unit completes it training cycle it does so with a significantly different mix of enlisted personnel. This puts a heavier weight on the officer corps and probably limits the level at which tactical and operation proficiency can be achieved.62 When ground forces conscription was reduced to a 2-year commitment in early 1999, this situation became even more serious, as up to one-half of all recruits would be first-year soldiers.

Future TrajectoriesThe Chinese ground forces have undergone a tumultuous two decades, marked by significant personnel cuts and organizational restructuring. The army also has suffered an important diminution in institutional reputation, thanks to its disastrous performance in Vietnam in 1979 and its brutality in Tiananmen Square in 1989, as well as shrinking institutional equity at the hands of ascendant air, naval, and missile service branches. Despite these upheavals, however, the army appears to have established the parameters for the type of force it would like to become: a smaller, more rapidly deployable, combined arms force equipped with weapons that increase the range from which it can strike the enemy. To achieve this goal, many of the organizational changes outlined above will need to be continued and even expanded. In particular, the downsizing of the ground forces remains the necessary precondition for modernization since a smaller force frees up budget monies for the essential equipment and training goals of the army. Following the conclusion of a reportedly successful effort from 1996 to reduce the PLA by 500,000 personnel, Jiang Zemin in 1998 asserted that "further troop reduction may be required to ensure that the troops are well-equipped and highly-mobile."63 Outside observers believe that the PLA, through a mix of genuine cuts, transfers, and needed recategorization of personnel, could cut a surprisingly large number of troops with little tangible impact on PLA capabilities. Blasko opines that "a reduction of one million from the 2.2 million-strong ground forces [note: this project was made in 1996, prior to the current round of reductions] conducted over the next 12 years would have no adverse impact on the PLA's ability to project force beyond their borders."64 Much of this cut could be achieved simply by disaggregating civilian defense employees (wenzhi ganbu) from active-duty military personnel. Additional transfers will likely increase the size of the reserves and the People's Armed Police. Augmentation of the PAP would potentially free the PLA from the specter of the internal security mission. As Blasko writes: Strengthening the PAP will make intervention by the active duty PLA less necessary, and therefore less likely, in a future domestic crisis (though always an alternative). Both the PAP and PLA will also be able to focus on and train more to perform their respective primary missions, rather than spending undue amounts of time on secondary missions. As the PLA becomes more technically advanced and complex, it will become less suitable for domestic security missions and will require more specific, intensive training to maintain its proficiency in its mission to defend China from external foes.65 Similarly, Blasko believes the downsizing of the PLA will have a direct impact upon the reserves: Much of the equipment and many of the personnel affected by reductions in the ground forces (who do not go to the PAP) in the next decade can be expected to find their way into the reserves. Eventually, the reserves could outnumber the total of PLA active duty forces, perhaps up to a total of 2 million if the PLA undergoes another 500,000-man reduction. A larger number of reserves than active duty forces would not be unique to the PLA. A larger reserve force also would be able to assist many of the disaster relief and community service missions that the PLA, PAP, and militia are often called to perform.66 The future therefore could witness the emergence of a much more variegated force, with sharper definitions of division of labor among mainline, paramilitary, reserve, militia, and civilian defense personnel. For the mainline units, downsizing also makes possible many other necessary element of future progress. At a fundamental level, the reductions in force will save money that can be spent on other priorities. As the force becomes smaller, for example, it becomes easier to outfit the remaining troops with advanced weapons and equipment. Moreover, the remaining troops will be able to undergo more training using these new weapons. This will undoubtedly be a slow process. If pursued with deliberate commitment, however, the result could be dramatically reformed Chinese ground forces, focused on the missions of the 21st century.

Notes1David Shambaugh, unpublished manuscript. [BACK] 2Acknowledgments for this essay must first begin with a heavy dose of modesty, humility, and proper attribution. The topic of Chinese ground forces is not my area of expertise, and this essay has drawn from the excellent opus of work on the subject. In particular, I must mention the contributions of Dennis J. Blasko, a former ground-pounder who has spent a career tracking the activities of the men in green. The proliferation of footnotes from his works are a testament to his contribution, which has frankly left few if any stones unturned. [BACK] 3Dennis J. Blasko, "PLA Force Structure: A 20-Year Retrospective," in Seeking Truth from Facts, ed. James C. Mulvenon and Andrew N.D. Yang (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2001). [BACK] 4For the best explication of PMOC, see Harlan W. Jencks, "People's War Under Modern Conditions: Wishful Thinking, National Suicide, or Effective Deterrent?" China Quarterly 98 (June 1984), 305-319. [BACK] 5Blasko, "PLA Force Structure: A 20-Year Retrospective." [BACK] 8The precise structure of the group army is discussed in the later organization section of this essay. [BACK] 9Yitzhak Shichor, "Demobilization: The Dialectics of PLA Troop Reductions," China Quarterly 146 (June 1996), 336-359. [BACK] 10"'Law of the People's Republic of China on National Defense,' Adopted at the Fifth Session of the Eight National People's Congress on March 14, 1997," Xinhua Domestic Service, in Foreign Broadcast Information Service--China (henceforth FBIS--China), March 14, 1997. [BACK] 11David Finkelstein, "China's National Military Strategy," The PLA in the Information Age, ed. James C. Mulvenon and Andrew N.D. Yang (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 1999). [BACK] 12Dennis J. Blasko, Philip T. Klapakis, and John F. Corbett, Jr., "Training Tomorrow's PLA: A Mixed Bag of Tricks," China Quarterly 146 (June 1996), 522. [BACK] 13Dennis J. Blasko, "A New PLA Force Structure," The PLA in the Information Age, ed. James C. Mulvenon and Andrew N.D. Yang (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 1999). [BACK] 14Contrary to popular opinion, the phrase limited, local war under high-tech conditions is not a doctrine but a description of the universe of conflict scenarios deemed most likely in the short to medium term by the leadership. [BACK] 15Blasko, Klapakis, and Corbett, 489. [BACK] 18Information Office of the State Council of the People's Republic of China, China's National Defense, July 1998. [BACK] 19These specific numbers are derived by multiplying white paper percentages by figures of 2.2 million, 265,000, and 470,000, found in International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance, 1996/97 (London: Oxford University Press, 1996), 179-181. [BACK] 20Blasko, "A New PLA Force Structure." [BACK] 22Dennis J. Blasko, "PLA Ground Forces: Moving towards a Smaller, More Rapidly Deployable, Modern Combined Arms Force," The PLA as Organization, ed. James C. Mulvenon and Andrew N.D. Yang (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 2002). [BACK] 23Blasko, "PLA Ground Forces." [BACK] 24The best study of the PAP is Murray Scot Tanner, "The Institutional Lessons of Disaster: Reorganizing the People's Armed Police after Tiananmen," in The PLA as Organization. [BACK] 25International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance, 1997/98, 179; and Liu Hsiao-hua, "Armed Police Force: China's 1 Million Special Armed Troops." [BACK] 26Blasko, "A New PLA Force Structure." [BACK] 27Blasko, "PLA Ground Forces." [BACK] 28Liu Hsiao-hua, "Jiang Zemin Convenes Enlarged Meeting of Central Military Commission." [BACK] 29International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance, 1996/97, 186. [BACK] 30Tai Ming Cheung, "Reforming the Dragon's Tail: Chinese Military Logistics in the Era of High-Technology Warfare and Market Economics," in China's Military Faces the Future, ed. James R. Lilley and David Shambaugh (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 1999), 236. [BACK] 31Blasko, Klapakis, and Corbett, 517. [BACK] 32Blasko, "PLA Force Structure: A 20-Year Retrospective." [BACK] 33U.S. DOD Report to Congress Pursuant to FY00 National Defense Authorization Act, June 2000. [BACK] 34Andrew N.D. Yang and Milton Wen-Chung Liao, "PLA Rapid Reaction Force: Concept, Training and Preliminary Assessment," in The PLA in the Information Age. [BACK] 35Blasko, "PLA Ground Forces." [BACK] 37U.S. DOD Report to Congress. [BACK] 38Li Xuanqing (Jiefangjun Bao) and Ma Xiaochun (Xinhua), "Armed Forces Communications Become Multidimensional," Xinhua, FBIS-China, July 16, 1997. [BACK] 39Liu Dongsheng, "Telecommunications: Greater Sensitivity Achieved--Second of Series of Reports on Accomplishments of Economic Construction and Defense Modernization," Jiefangjun Bao, September 8, 1997, 5, in FBIS-China, October 14, 1997. [BACK] 40See Tang Shuhai, "All-Army Public Data Exchange Network Takes Initial Shape," Jiefangjun Bao, September 18, 1995, in FBIS-China. [BACK] 41Cheng Gang and Li Xuanqing, "Military Telecommunications Building Advances Toward Modernization With Giant Strides," Jiefangjun Bao, July 17, 1997, in FBIS-China. [BACK] 42Tang Shuhai, "All-Army Public Data Exchange Network Takes Initial Shape." [BACK] 44"PLA Helps With Fiber-Optic Cable Production," Xinhua, November 13, 1995, in FBIS-China, November 13, 1995. [BACK] 45Luo Yuwen, "PLA Stresses Military-Civilian Unity," Xinhua Domestic Service, March 5, 1999. [BACK] 46"Domestic Fiber-Optic Cable Maker Unveils New Civilian, Military Products," October 6, 1997, in FBIS-China, October 6, 1997. [BACK] 47Cheng Gang and Li Xuanqing, "Giant Strides." [BACK] 48Li Xuanqing and Ma Xiaochun, "Armed Forces" Communications Become 'Multidimensional,'" Xinhua Domestic Service, July 16, 1997. [BACK] 49Blasko, "PLA Force Structure: 20-Year Retrospective." [BACK] 50"Army Seeks Mobility in Force Cuts," Jane's Defense Weekly, December 16, 1998, 24. [BACK] 51Blasko, Klapakis, and Corbett, 494. [BACK] 52Harlan W. Jencks, From Muskets to Missiles: Politics and Professionalism in the Chinese Army 1945-1981 (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1982), 47-48. [BACK] 53Blasko, "A New PLA Force Structure." [BACK] 54Blasko, Klapakis, and Corbett, 491. [BACK] 55Blasko, "A New PLA Force Structure." [BACK] 56Kuan Cha-chia, "Military Authorities Define Reform Plan; Military Academies to Be Reduced by 30 Percent," Kuang chiao ching, no. 306, March 16, 1998, 8-9, in FBIS-China, March 25, 1998. [BACK] 57Blasko, Klapakis, and Corbett, 517. [BACK] 63Liu Hsiao-hua, "Jiang Zemin Convenes Enlarged Meeting of Central Military Commission, Policy of Fewer but Better Troops Aims at Strengthening Reserve Service Units," Kuang chiao ching, no. 308, May 16, 1998, 50-53, in FBIS-China, June 10, 1998. [BACK] |

| Table of Contents I Chapter Seven

|

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|