Nuclear Nonproliferation: Implications of the U.S./North Korean Agreement on Nuclear Issues

(Letter Report, 10/01/96, GAO/RCED/NSIAD-97-8)

Pursuant to a congressional request, GAO reviewed the agreement between

the United States and North Korea that addresses the threat of North

Korean nuclear proliferation, focusing on whether: (1) the agreement is

a non-binding political agreement; (2) the United States could be held

financially liable for a nuclear accident at a North Korean reactor

site; (3) North Korea is obligated to pay to upgrade its existing

electric power distribution system; and (4) the agreement is being

implemented consistent with the applicable laws governing the transfer

of U.S. nuclear components, materials, and technology.

GAO found that: (1) the United States executed a non-binding political

agreement, since it would not have been in the United States' interest

to legally obligate itself to provide nuclear reactors and interim

energy to North Korea; (2) the Korean Peninsula Development Organization

has taken steps to protect its members from nuclear liability claims by

North Korea and third-party countries by establishing a risk management

program; (3) North Korea is not legally obligated to pay for upgrades to

its electric power distribution system; (4) the Departments of State and

Energy have complied with the statutory requirements governing

technology transfers to North Korea; and (5) State has secured a

commitment from North Korea to execute an agreement for peaceful nuclear

cooperation if needed.

--------------------------- Indexing Terms -----------------------------

REPORTNUM: RCED/NSIAD-97-8

TITLE: Nuclear Nonproliferation: Implications of the U.S./North

Korean Agreement on Nuclear Issues

DATE: 10/01/96

SUBJECT: Nuclear proliferation

Arms control agreements

Nuclear weapons

Electric power transmission

International cooperation

Technology transfer

Nuclear reactors

Government liability (legal)

Nuclear facility safety

Atomic energy defense activities

IDENTIFIER: South Korea

Japan

Australia

Canada

Chile

Finland

Indonesia

New Zealand

North Korea

Malaysia

******************************************************************

** This file contains an ASCII representation of the text of a **

** GAO report. Delineations within the text indicating chapter **

** titles, headings, and bullets are preserved. Major **

** divisions and subdivisions of the text, such as Chapters, **

** Sections, and Appendixes, are identified by double and **

** single lines. The numbers on the right end of these lines **

** indicate the position of each of the subsections in the **

** document outline. These numbers do NOT correspond with the **

** page numbers of the printed product. **

** **

** No attempt has been made to display graphic images, although **

** figure captions are reproduced. Tables are included, but **

** may not resemble those in the printed version. **

** **

** Please see the PDF (Portable Document Format) file, when **

** available, for a complete electronic file of the printed **

** document's contents. **

** **

** A printed copy of this report may be obtained from the GAO **

** Document Distribution Center. For further details, please **

** send an e-mail message to: **

** **

** <info@www.gao.gov> **

** **

** with the message 'info' in the body. **

******************************************************************

Cover

================================================================ COVER

Report to the Chairman, Committee on Energy and Natural Resources,

U.S. Senate

October 1996

NUCLEAR NONPROLIFERATION -

IMPLICATIONS OF THE U.S./NORTH

KOREAN AGREEMENT ON NUCLEAR ISSUES

GAO/RCED/NSIAD-97-8

The U.S./North Korean Agreement

(170269)

Abbreviations

=============================================================== ABBREV

DOE - Department of Energy

DPRK - Democratic People's Republic of Korea

GAO - General Accounting Office

IAEA - International Atomic Energy Agency

KEDO - Korean Peninsula Energy Development Organization

LWR - light-water reactor

MW(e) - megawatt electric

NPT - Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty

NRC - Nuclear Regulatory Commission

Letter

=============================================================== LETTER

B-272530

October 1, 1996

The Honorable Frank H. Murkowski

Chairman, Committee on Energy

and Natural Resources

United States Senate

Dear Mr. Chairman:

North Korea is suspected of having produced material usable for

manufacturing nuclear bombs. On October 21, 1994, the United States

and North Korea concluded an agreement known as the "Agreed

Framework" to address the threat posed by North Korea's nuclear

program and to otherwise diffuse the tensions that have existed on

the Korean Peninsula since the period of the Korean War.\1 Under the

agreement, the United States made a commitment to, among other

things, create an international consortium of member countries--the

Korean Peninsula Energy Development Organization (KEDO)--to replace

North Korea's graphite-moderated reactors with light-water reactors.

In exchange, North Korea agreed to, among other things, stop

operating and constructing its reactors and related facilities and

eventually dismantle them. The light-water reactors are preferred

over graphite-moderated reactors because, in part, they do not

produce materials as easily used to make nuclear weapons.\2

This report responds to your request that we determine whether (1)

the Agreed Framework is a nonbinding political agreement, (2) the

United States could be held financially liable for a nuclear accident

at the North Korean reactor site, (3) North Korea has obligated

itself to pay the cost of upgrading its existing electricity power

distribution system, and (4) the agreement is being implemented

consistent with the applicable laws governing the transfer of U.S.

nuclear components, materials, and technology.

--------------------

\1 "Agreed Framework Between the United States of America and the

Democratic People's Republic of Korea [DPRK]," commonly known as

North Korea.

\2 Reactors require a substance called a "moderator" to achieve a

nuclear chain reaction. The type of moderator used varies, depending

on the plant's design. North Korea uses graphite as the moderator

for its reactors, whereas water is used in light-water reactors.

Graphite-moderated reactors are more useful for producing

plutonium-239--the most desirable isotope for making nuclear weapons.

The fuel rods in light-water power reactors stay in the reactors

longer, creating spent fuel with higher concentrations of other

isotopes that, according to the Department of State, make the

material (1) more dangerous to handle because of high levels of

radiation and (2) more difficult to produce bombs with predictable

yields.

RESULTS IN BRIEF

------------------------------------------------------------ Letter :1

The Agreed Framework can be properly described as a nonbinding

political agreement. Therefore, its pledges--including those

involving financial outlays--are not legally enforceable. Agreements

of this type do not require the Congress's prior involvement or

approval and, as we have suggested in the past, can have the effect

of pressuring the Congress to appropriate money to implement an

agreement with which it had little involvement. According to the

Department of State, the United States executed a nonbinding

agreement because it would not have been in the country's interest to

legally obligate itself to provide the reactors and interim energy to

North Korea.

Our analysis of the existing nuclear liability protections confirms

that the foundation of KEDO's risk protection program is in place.

KEDO is aware that further steps need to be taken and, as a result,

plans to obtain additional protections to ensure that KEDO and its

members are fully shielded from possible liability claims. Without

knowing the contents of these future protections, it is not possible

to fully assess the adequacy of the liability protection that will be

provided to KEDO and its members. Nevertheless, our assessment of

the liability provisions in the KEDO and supply agreements and KEDO's

intention to secure additional protections, suggests that KEDO and

its members--including the United States--will be adequately

protected against nuclear damage claims from North Korea and

third-party countries. Finally, according to KEDO, it will not ship

any fuel assemblies to North Korea or allow the reactors to be

commissioned unless and until KEDO and its members consider that all

aspects of the risk protection program are in place.

North Korea's existing electricity transmission and distribution

system (power grid) will need to be modernized to distribute the

electricity generated by the two light-water reactors being provided.

Upgrading the power grid could cost as much as $750 million. Thus

far, no party has obligated itself to pay for the upgrade. The

United States and KEDO maintain that North Korea is responsible;

however, North Korea has not yet legally obligated itself to pay.

This circumstance leaves open the possibility that, in the future,

North Korea could exert pressure on others to pay for upgrading the

grid.

The Departments of State and Energy have taken steps to carry out the

requirements of the Atomic Energy Act of 1954, as amended. It is too

early to say whether the United States and North Korea will need to

conclude an agreement for cooperation--as set forth in the

act--because decisions have not yet been made about what, if

anything, the United States will supply for the reactors.

Nevertheless, an agreement appears likely because a U.S. firm

currently supplies a major component for the reactors that are to be

delivered. State is prepared for the possibility that an agreement

will be needed and has already secured North Korea's commitment to

execute one if it becomes necessary. The Department of Energy is

also complying with the act's requirement to authorize the transfers

of U.S. reactor technology abroad. In fact, the five authorizations

it has granted so far contain additional safeguards to address the

concerns about technology transfers to North Korea.

BACKGROUND

------------------------------------------------------------ Letter :2

North Korea has several nuclear facilities that, collectively, have

the potential to produce nuclear fuel for weapons. Most are located

at Yongbyon, 60 miles north of Pyongyang. The major installations

include (1) a 5-megawatt electric (MW(e)) research reactor, (2) two

larger reactors that were under construction--a 50-MW(e) reactor in

Yongbyon and a 200-MW(e) reactor at Taechon, and (3) a plutonium

reprocessing facility.\3

The 5-MW(e) research reactor was constructed in the 1980s and is

thought to be capable of producing about 7 kilograms of plutonium

annually. The two reactors under construction were expected to yield

another 200 kilograms of plutonium annually--enough plutonium for

about 50 atomic bombs per year.\4

The reprocessing facility separates weapons-grade plutonium-239 from

the reactor's spent fuel. The reactor facilities reportedly were not

attached to a power grid, increasing concern that the facilities were

intended to produce material for making nuclear weapons rather than

for producing electricity.

Under the Agreed Framework, North Korea made a commitment to, among

other things, (1) remain a party to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation

Treaty--a treaty aimed at preventing the spread of nuclear weapons;

(2) freeze the operation and construction of its graphite-moderated

reactors and related facilities, including the reprocessing plant,

and eventually dismantle them; and (3) cooperate with the United

States to safely store and dispose of the spent fuel in its

possession. In return for these concessions, the United States

agreed to, among other things, create an international consortium of

member countries to (1) replace North Korea's graphite-moderated

reactors with a light-water reactor project by a target date of 2003

and (2) supply North Korea with energy--heavy oil for heating and

electricity production--pending the completion of the first

light-water reactor. (App. I provides additional information about

the contents of the agreement.)

According to State and other administration sources, the agreement to

replace North Korea's 5-MW(e) reactor and the two larger reactors

under construction was needed because, unlike light-water reactors,

the North Korean reactors and related nuclear facilities were

particularly well suited to produce nuclear materials. In addition,

if the two nuclear reactors had been completed, North Korea would

have vastly increased the amount of nuclear material in its

possession. Finally, North Korea was believed to be doubling its

plutonium separation capacity. (App. II provides a chronology of

events preceding the Agreed Framework, including information on North

Korea's suspected reprocessing activities.)

On March 9, 1995, the United States, Japan, and the Republic of Korea

(South Korea) founded KEDO to finance and supply the reactors (the

"light-water reactor project") and interim energy.\5 On December 15,

1995, KEDO and North Korea concluded negotiations on an agreement for

supplying the project (supply agreement).\6

The supply agreement obligates KEDO to provide two light-water

reactors--each with a generating capacity of about 1,000 MW(e)--to

North Korea. The reactors will be an advanced version of a design of

U.S. origin and technology currently under construction in South

Korea. The agreement specifies that KEDO will finance the cost of

the project--expected to exceed $4 billion--and that North Korea will

repay the interest-free loan over an extended period.\7

The supply agreement authorizes KEDO to select a prime contractor to

carry out the project. KEDO selected the Korea Electric Power

Corporation--the South Korean, partially state-owned utility with

experience in the construction, operation, and maintenance of nuclear

power plants. Preliminary construction at the reactor site is

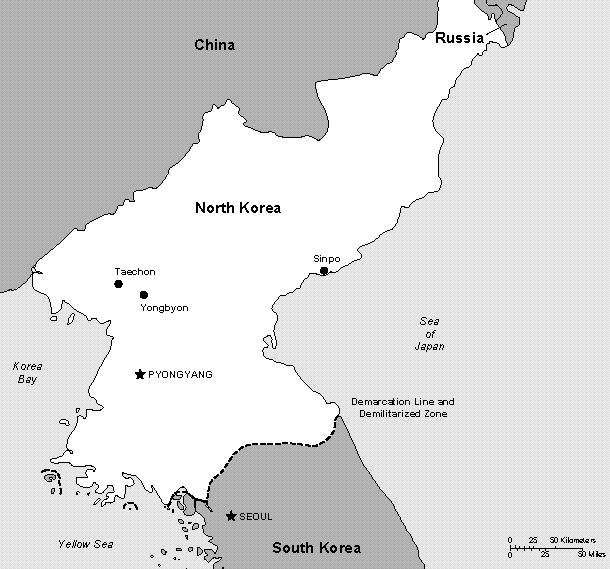

expected to begin in the fall of 1996 at Sinpo, North Korea. See

figure 1 for a map identifying Sinpo and other relevant North Korean

sites.

Figure 1: Sinpo and Other

Relevant North Korean Sites

--------------------

\3 When the Agreed Framework was concluded, the two larger reactors

were expected to be completed in the mid-1990s.

\4 In January 1994, the Department of Energy reported that, depending

on the technology used, as little as four kilograms of plutonium is

sufficient to manufacture a nuclear bomb.

\5 "Agreement on the Establishment of the Korean Peninsula Energy

Development Organization." This agreement is hereafter described as

the "KEDO agreement." Through the end of August 1996, six other

countries--Australia, Canada, Chile, Finland, Indonesia, and New

Zealand--had joined KEDO. Efforts continue to recruit additional

KEDO members and, according to the State Department, Argentina,

Brazil, and France are expected to become members soon.

\6 "Agreement on Supply of a Light-Water Reactor Project to the

Democratic People's Republic of Korea Between the Korean Peninsula

Energy Development Organization and the Government of the Democratic

People's Republic of Korea."

\7 KEDO receives funds through contributions from members and

nonmembers. South Korea and Japan are expected to provide the

majority of the funds needed for the light-water reactor project.

THE AGREED FRAMEWORK CAN BE

PROPERLY CHARACTERIZED AS A

NONBINDING POLITICAL AGREEMENT

------------------------------------------------------------ Letter :3

The Agreed Framework can be properly described as a nonbinding

political agreement. The Agreed Framework's broad pledges--as later

implemented in more defined, binding agreements--and the subsequent

actions of the parties suggest that both the United States and North

Korea regarded the Agreed Framework as a nonbinding, preliminary

arrangement.

Officials at State said that the United States executed a nonbinding

political document because it would not have been in the United

States' interest to accept an internationally binding legal

obligation to provide the reactors and interim energy to North Korea.

Instead, they said that the United States wanted the flexibility to

respond to North Korea's policies and actions in implementing the

Agreed Framework--flexibility that binding international agreements,

such as a treaty, would not have provided.

According to State, its position that the agreement is nonbinding is

supported by (1) the agreement's language and form, which are not

typical of binding international agreements, and (2) the fact that

neither side has since acted in a manner that is inconsistent with

such an understanding. In connection with the language used in the

Agreed Framework, State maintains that the most important indicator

of the parties' intent is the absence of the word "agreed" and the

use, instead, of the word "decided" in the agreement's preamble.\8

In our view, the language of the Agreed Framework is not entirely

clear about the intent of the United States and North Korea to

establish a nonbinding political agreement. Nevertheless, the

agreement's tone and form and, particularly, the subsequent actions

of the United States and North Korea suggest that the Agreed

Framework was intended to be a nonbinding international agreement.

The agreement consists of four general pledges, all of which are

consistent with the kind of broad declaration of goals and principles

that characterize nonbinding international agreements.\9 Furthermore,

the agreement omits provisions--such as provisions on the process for

amending the agreement and for resolving disputes--that would

normally be included in a binding agreement.

The subsequent actions by the United States and North Korea also

suggest that the Agreed Framework was intended to be a nonbinding,

preliminary arrangement. In a joint press statement on June 13,

1995, at Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, the two countries reaffirmed their

"political commitments to implement the . . . Agreed Framework."

Of greater significance was the conclusion of both the KEDO and

supply agreements--two binding international agreements that

implement the Agreed Framework's provisions for supplying the

reactors and interim energy to North Korea.

Executing nonbinding international agreements like the Agreed

Framework does not require prior congressional involvement or

approval and, as we have suggested in the past, can have the effect

of pressuring the Congress to appropriate moneys to implement an

agreement with which it had little involvement.\10 For the North

Korean project, this issue is complicated by the political importance

of the agreement and the existence of the KEDO and supply

agreements--neither of which received formal congressional approval.

Taken together, these binding international agreements--described in

very concrete and specific terms--effectively incorporate the Agreed

Framework's provisions for supplying the reactors and energy to North

Korea.

If the Agreed Framework had been structured as a treaty or some other

form of binding international agreement, its pledges would have

established legally binding commitments, under both international law

and the domestic law of the United States. It would also have been

subjected to greater formal congressional oversight. (App. III

provides our full analysis on the structure of the Agreed Framework,

including our analysis of the structure's impact on (1) the legal

enforceability of the agreement and (2) congressional oversight.)

--------------------

\8 The preamble of the agreement states that "[t]he United States and

the DPRK [North Korea] decided to take the following actions for the

resolution of the nuclear issue."

\9 App. I provides information about the agreement, including its

four general pledges.

\10 See 59 Comp. Gen. 369, 372 (1980).

EXISTING AND PLANNED NUCLEAR

LIABILITY PROTECTIONS APPEAR

ADEQUATE

------------------------------------------------------------ Letter :4

According to KEDO, it places a high priority on protecting the

present and future members of KEDO against the risk of nuclear

liability that may arise from North Korea's light-water reactor

project. As a result, KEDO developed a "comprehensive risk

management program" to protect itself and its member countries. The

foundation of the risk management program is contained in the KEDO

and supply agreements. Over time, KEDO plans to negotiate additional

protections to fully shield itself and its members from the risk of

nuclear liability. Without knowing the contents of these future

protections, it is not possible to fully assess the adequacy of the

liability protection that will be provided to KEDO and its members.

Nevertheless, the provisions already negotiated and KEDO's plan to

secure additional protections, suggest that KEDO and its members will

be adequately protected. Moreover, according to KEDO, it will not

ship any fuel assemblies to North Korea or allow the reactors to be

commissioned unless and until KEDO and its members consider that all

aspects of the risk management program are in place.

PROTECTIONS AGAINST NORTH

KOREAN NUCLEAR CLAIMS

---------------------------------------------------------- Letter :4.1

The supply and KEDO agreements contain a number of protections that

are intended to preclude North Korea from making claims against KEDO

or KEDO members for damages from a nuclear incident. The principal

protection requires North Korea to set up a legal mechanism for

satisfying all claims brought within North Korea. The supply

agreement also contains a provision precluding North Korea from

bringing claims against KEDO for any nuclear damage or loss, and both

the supply and KEDO agreements contain a general

limitation-of-liability provision that appears to cover nuclear

damage.

The principal protection in the supply agreement requires North Korea

to "ensure that a legal and financial mechanism is available for

satisfying claims brought within North Korea for damages from a

nuclear incident."\11 Consistent with international practice, the

agreement specifies that "[t]he legal mechanism shall include the

channeling of liability in the event of a nuclear incident to the

operator on the basis of absolute liability."\12 North Korea must

also ensure that the operator--a North Korean entity--is able to

satisfy potential claims for nuclear damage. North Korea has not yet

enacted legislation--referred to as channeling

legislation--satisfying its responsibilities under the Agreed

Framework. In the next few years, KEDO intends to help North Korea

draft the required legislation and to monitor North Korea's efforts

to establish the financial mechanism for paying possible nuclear

damage claims.

The supply agreement also contains a second provision that precludes

North Korea from bringing any nuclear damage or loss claims against

KEDO and its contractors and subcontractors. The scope of this

provision is broad and, according to KEDO, covers claims for nuclear

damage caused both before and after the reactors have been turned

over to North Korea. A third provision explicitly states that North

Korea shall seek recovery solely from the property and assets of KEDO

for any claims arising (1) under the supply agreement or (2) from any

actions of KEDO and its contractors and subcontractors.

Correspondingly, the KEDO agreement contains a general

limitation-of-liability provision which specifies that the members of

KEDO are not liable for the actions or obligations of KEDO.

Taken together, the described provisions appear to bar North Korea

from making any nuclear claims against KEDO's member

countries--including the United States--in North Korean courts.

However, none of the existing provisions explicitly precludes claims

by North Korean nationals or North Korean nongovernmental entities.

According to KEDO, it intends to ensure that the channelling

legislation, to be enacted by North Korea, protects KEDO and its

members from possible claims from these sources.

--------------------

\11 As used in the supply agreement, a "nuclear incident" is "any

occurrence or series of occurrences having the same origin, which

causes nuclear damage."

\12 The practice of "channeling liability" to the operator of a

nuclear plant is commonly used in the field of nuclear liability.

The practice requires a nuclear plant operator to assume full

liability for all damage resulting from a nuclear incident.

PROTECTIONS AGAINST NUCLEAR

CLAIMS MADE BY THIRD PARTIES

---------------------------------------------------------- Letter :4.2

The largest concern of KEDO and its members may be the nuclear damage

claims brought by third parties in courts and tribunals outside of

North Korea. Unlike the Paris and Vienna Conventions--the principal

international conventions on third party nuclear liability--which

include provisions limiting the jurisdiction for hearing claims to

the courts in the country where the nuclear incident occurs, the

supply agreement does not preclude claims from being brought in

jurisdictions outside of North Korea.

It is generally recognized that a country is liable for damage caused

to the environment of another country. Thus, once North Korea

assumes control over the reactors, North Korea and the operator of

the reactors would likely become the primary targets of claims for

nuclear damage incurred outside of the country. Nevertheless,

lawsuits could also be brought against KEDO and its members. To

address this possibility, the supply agreement requires North Korea

to (1) enter into an agreement for indemnifying KEDO and (2) secure

nuclear liability insurance or other financial security to protect

KEDO and its contractors and subcontractors from any claims by third

parties resulting from a nuclear incident at the North Korean

reactors. Also, as discussed earlier, the KEDO agreement contains a

general limitation-of-liability provision that appears to cover

nuclear damage liability for lawsuits brought outside of North

Korea.\13

The provision requiring indemnification and insurance protections is

intended to provide KEDO with adequate protection against suits

brought in courts outside of North Korea. Even so, as the provision

is written, the indemnity and insurance protections extend only to

KEDO and its contractors and subcontractors and not, specifically, to

KEDO's members. Thus, it is not clear that these protections would

cover possible awards by foreign courts against individual KEDO

members, including the United States. Furthermore, the supply

agreement does not address the extent of the indemnity and insurance

protections that North Korea must provide, leaving questions about

whether North Korea will be required to indemnify KEDO (1) for the

entire amount of any damage awards obtained in foreign courts or for

some fixed, lesser amount and (2) if North Korea's insurance and

other financial security do not cover all claims.

KEDO is aware of these issues and, as a result, plans to build upon

the foundation of the existing coverage to fully shield KEDO and its

members from possible nuclear liability claims by third parties. For

example, in a future agreement--termed a "protocol"--KEDO intends to

ensure that the specific indemnity and insurance protections that it

negotiates also extend to KEDO's members.\14 In addition, according

to KEDO, the protocol will establish the level of indemnity

protection to be provided--an amount which, at a minimum, will be

consistent with international norms. KEDO also plans to negotiate

additional liability, indemnification, and insurance protections in

its future contracts with contractors and subcontractors. According

to KEDO, it will neither ship any fuel assemblies to the North Korea

nor allow the reactors to be commissioned "[u]nless and until KEDO

and its members consider that all aspects of the risk management

program are in place."

--------------------

\13 Furthermore, as discussed in appendix IV, if a foreign court

entertains a nuclear damage claim against the United States, the

United States could assert the defense of "sovereign immunity" as a

bar to the court's hearing the claim.

\14 KEDO expects to begin negotiations on the agreement with North

Korea in early 1997.

POTENTIAL LIABILITY DURING

TESTING OF THE REACTORS

---------------------------------------------------------- Letter :4.3

KEDO also plans to address potential liabilities that could arise

from the operation of the reactors during the test period--before

North Korea assumes control of them.\15 KEDO contends that the

radiological effects of any discharges or omissions would be minimal,

unlikely to give rise to substantial claims, and, in all likelihood,

limited to North Korea. While KEDO views its potential liability as

minimal, it still wants to ensure that it is never the "operator" of

the reactors because it lacks the technological capability to perform

the tests and because it wants to avoid the potential liabilities

that could flow to the "operator" under the channeling legislation.

Thus, KEDO plans to structure the arrangements for testing the

reactors so that another party--such as North Korea or a KEDO

contractor--will operate the reactors during the test period. While

the respective views of these entities is not known, it seems

unlikely that another party would assume the responsibility for

testing the reactors without being compensated by KEDO. (App. IV

provides our full analysis of the nuclear liability issue.)

--------------------

\15 Under the supply agreement, KEDO is responsible for testing the

reactors.

QUESTIONS REMAIN ABOUT NORTH

KOREA'S OBLIGATION TO PAY FOR

UPGRADING ITS ELECTRICITY POWER

GRID

------------------------------------------------------------ Letter :5

North Korea's existing electricity transmission and distribution

system is inadequate to handle the electricity that would be

generated by two new 1,000- MW(e) light-water reactors. As a result,

much of North Korea's existing equipment will need to be replaced or

modernized before the reactors can be used. According to State, the

upgrade could include the replacement or modernization of substations

and transformers, transmission towers, and high- voltage cables.

State estimates that the cost of the upgrade could reach $750

million.

None of the agreements concluded to date creates a legal obligation

to pay for the grid upgrade.\16 The State Department and KEDO

maintain that North Korea is responsible;\17 however, North Korea has

not yet legally obligated itself to pay. State and KEDO point to a

December 15, 1995, letter from KEDO to North Korea as evidence of

their view that North Korea is responsible. The letter--attached to

the supply agreement--pledges KEDO's nonfinancial assistance to North

Korea "in its own [North Korea's] efforts to obtain through

commercial contracts . . . such power transmission lines and

substation equipment as may be needed to upgrade the DPRK [North

Korean] electric power grid." According to State, the letter was (1)

requested by North Korea, (2) drafted in consultation with North

Korea, and (3) accepted in conjunction with the signing ceremony for

the supply agreement--factors that, in State's view, constitute North

Korea's acknowledgement of its responsibility for paying for the grid

upgrade. Nevertheless, State agrees that North Korea did not sign

the letter and that North Korea has not legally obligated itself to

pay for the upgrade. This leaves open the possibility that, in the

future, North Korea could exert pressure on others to pay for the

grid upgrade.

--------------------

\16 The supply agreement specifies that North Korea is legally

obligated to provide a stable supply of electricity for the

commissioning of the two light-water reactors. This obligation is

unrelated to the issue of upgrading the power grid for its later use

in distributing electricity generated by the reactors. According to

State, KEDO did not formally seek North Korea's legal commitment to

upgrade the power grid because it would have been illogical for North

Korea to owe KEDO a legal duty to upgrade its own grid.

\17 According to a State Department official who participated in the

negotiations, North Korea persistently sought KEDO's agreement to

provide the grid upgrade, but KEDO consistently refused.

IMPLEMENTATION OF THE AGREED

FRAMEWORK IS CONSISTENT THUS

FAR WITH APPLICABLE U.S. LAWS

------------------------------------------------------------ Letter :6

The Atomic Energy Act of 1954, as amended (the act), specifies the

requirements for the peaceful transfer of U.S. nuclear equipment,

materials, and technology abroad.\18 Thus far, both State and the

Department of Energy (DOE) have complied with their statutory

obligations under the act. In fact, the five authorizations granted

by DOE so far contain additional safeguards to address the concerns

about the technology transfers to North Korea.

--------------------

\18 Act of Aug. 30, 1954, 68 Stat. 921. The act was amended by the

Nuclear Non-Proliferation Act of 1978, Pub. L. 95-242, 92 Stat.

120.

AN AGREEMENT FOR COOPERATION

WILL BE NEGOTIATED IF NEEDED

---------------------------------------------------------- Letter :6.1

The act requires the United States to execute an agreement for

peaceful nuclear cooperation with a recipient nation or group of

nations before exporting major reactor components or nuclear

materials. It is too early to say whether an agreement for

cooperation between the United States and North Korea will be

required because decisions about what, if anything, the United States

will supply for the reactors have not yet been made. These

uncertainties are likely to exist until at least the spring of 1997,

when arrangements for supplying some of the equipment may be

negotiated. Nevertheless, an agreement appears likely because a U.S.

firm, Combustion Engineering, Inc., supplies the coolant pumps--a

major reactor component--for the light-water reactors. State is

prepared for the possibility that an agreement will be needed and, as

part of the Agreed Framework, has already secured a commitment from

North Korea to execute one if it becomes necessary.\19 (App. V

provides information about the (1) reactors expected to be supplied

to North Korea, including information about possible U.S. transfers

of major reactor components, and (2) statutory requirements governing

such transfers.)

--------------------

\19 Similarly, the supply agreement between KEDO and North Korea

states, "[i]n the event that U.S. firms will be providing any key

nuclear components, the U.S. and the DPRK [North Korea] will

conclude a bilateral agreement for peaceful nuclear cooperation prior

to the delivery of such components."

DOE'S AUTHORIZATIONS FOR

TECHNOLOGY TRANSFERS ARE

PROCEEDING ACCORDING TO

APPLICABLE REQUIREMENTS

---------------------------------------------------------- Letter :6.2

The act precludes any U.S. person from directly or indirectly

producing special nuclear material outside of the United States

unless authorized by either an agreement for cooperation or the

Secretary of Energy. According to DOE officials, DOE considers all

transfers of nuclear technology, including training, as having the

potential to result in the production of special nuclear materials,

thus triggering the act's requirements. Because the United States

does not have an agreement for cooperation with North Korea,

transfers of technology must be authorized by the Secretary of

Energy.\20

DOE's regulations provide for two types of authorizations--general

and specific.\21 DOE permits U.S. nuclear power reactor technology

to be transferred to most countries under a general authorization.\22

Similar technology transfers to North Korea and 47 other countries,

however, must be specifically authorized.

Under DOE's regulations for a specific authorization, the Secretary

of Energy will approve an application if the Secretary

determines--with the concurrence of State and after consulting the

Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, the Nuclear Regulatory

Commission (NRC), the Department of Commerce, and the Department of

Defense--that the proposed activity would not be "inimical" to the

interests of the United States. In making the determination, the

Secretary must evaluate whether (1) the United States has an

agreement for nuclear cooperation with the recipient country; (2) the

country is a party to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty; (3) the

country has a full-scope safeguards agreement with the International

Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)\23 and, if not, whether the country has

accepted IAEA's safeguards on the proposed activity; (4) other

nonproliferation controls or conditions may be applicable to the

proposed activity; (5) the proposed U.S. activity is relatively

significant; (6) comparable assistance is available from other

sources; and (7) other factors exist that may bear upon the

political, economic, or security interests of the United States,

including U.S. obligations under international agreements or

treaties.

Through August 1996, five U.S. companies, including Combustion

Engineering, Inc., had requested DOE's authorization to work on the

North Korean project. Combustion Engineering, Inc.'s August 9, 1995,

request to DOE indicated that because the North Korean reactors would

be based on the company's technology, the company expected to be

involved in most phases of the project's management, design,

manufacture, supply, training, and plant construction. The four

other U.S. companies requested DOE's authorization to perform a wide

range of architectural and engineering services and overall

management support on behalf of KEDO, its contractors, and

subcontractors.\24

DOE evaluated each of the requests, as required by its regulations,

and subsequently forwarded the analyses, together with its

recommendations on the proposed conditions for the transfers, to the

applicable U.S. agencies. State concurred with DOE's

recommendations--the only concurrence required.\25

The Secretary approved each of the authorizations, subject to

numerous conditions. Specifically, before any transfer, the United

States must receive North Korea's assurances that (1) any technology

transferred by the U.S. company would be used only for peaceful

nuclear power generation purposes and not for any military or

explosive purpose; (2) neither the transferred technology nor the

equipment based on it will be retransferred to another country

without the prior consent of the U.S. government; and (3) North

Korea will place the light-water reactors under IAEA's safeguards.

DOE also specified a number of conditions applicable to the U.S.

companies. Specifically, they must (1) ensure that the technology

transferred by the companies is limited to that necessary for the

licensing and safe operation of the reactors (and not technology that

would enable North Korea to design or manufacture either reactor

components or fuel) and (2) provide written quarterly reports to DOE

on their activities in support of the project and, whenever requested

by DOE, brief DOE and other U.S. government agencies on their

activities. DOE limited each of the authorizations to a period of 5

years, renewable by DOE in the light of experience and the

circumstances at that time.

Thus far, DOE has complied with its statutory and regulatory

requirements for granting the authorizations. In addition, the

conditions imposed on the authorizations indicate that DOE has sought

additional safeguards to address the concerns about possible

transfers of U.S. nuclear technology to North Korea. For example,

the five authorizations granted so far specify that DOE will suspend

the authorizations if either the United States or North Korea

"abrogates" the Agreed Framework or related agreements. The

authorizations also specify additional reporting requirements for the

transfers.\26 Finally, DOE's caution about the scope of any

technology that may be transferred by the companies is intended to

provide an additional safeguard for the proposed transfers.

--------------------

\20 State and DOE officials use the term "technology transfer" to

refer to activities that could result in the production of special

nuclear material.

\21 The procedures for granting the authorizations are detailed in

part 810 of DOE's regulations (10 C.F.R.). As a result, the

authorizations are generally called "part 810 authorizations."

\22 South Korea received Combustion Engineering, Inc.'s reactor

technology under a general authorization.

\23 IAEA is an international organization affiliated with the United

Nations that, among other things, is responsible for safeguarding

nuclear facilities to ensure that nuclear material is not diverted

for military or other nonpeaceful purposes.

\24 The other U.S. companies are Raytheon Engineers and

Constructors, Sargent & Lundy, Stone & Webster Engineering

Corporation, and Duke Engineering & Services, Inc. KEDO selected

Duke Engineering & Services, Inc., as its technical support

contractor in July 1996.

\25 The other agencies also responded favorably. NRC also commented

on a number of related matters. For example, NRC stressed the

importance of timely and continuing actions by the United States and

others to assist North Korea in developing a sound safety culture for

the project. NRC also stressed its strong support for the resolution

of outstanding questions about the amount of nuclear material in

North Korea's possession and the need for full safeguards inspections

by IAEA. Finally, NRC expressed concern about possible U.S. exports

of reactor fuel and major reactor components and noted that the

process of negotiating and obtaining legislative approval for an

agreement for cooperation between the United States and North Korea

"could raise significant [unspecified] difficulties. . . ."

According to the official who manages DOE's authorization process,

NRC's comments are typical of those it generally offers in its

replies to DOE. The Department of Defense did not comment on any of

the proposed authorizations.

\26 DOE's regulations require a U.S. company to submit a detailed

report of its activities within 30 days of beginning activities

covered by the authorization. Quarterly reports and periodic

briefings are not required. However, the regulations permit DOE to

request additional information.

OBSERVATIONS

------------------------------------------------------------ Letter :7

It is essential that KEDO not commission the reactors until full and

adequate liability protections are in place for KEDO and its members.

If these protections are not in place and an accident occurs at the

North Korean reactor site, the United States--as the leading

proponent of the project--and, perhaps, to a lesser extent, Japan and

South Korea, could be subjected to strong political and humanitarian

pressure to pay nuclear damage claims. KEDO recognizes the

importance of securing full and adequate protection and has committed

not to deliver the fuel and commission the reactors until KEDO and

its members are fully protected. We believe that it is vital for the

Congress to monitor KEDO's future efforts in this area, including

KEDO's (1) assistance to North Korea in developing the channeling

legislation and (2) efforts to secure full and adequate indemnity and

insurance to protect against claims in countries other than North

Korea.

AGENCY COMMENTS

------------------------------------------------------------ Letter :8

We provided copies of this report to State, DOE, and KEDO for their

review and comment. We met with State Department officials,

including an attorney from the Office of the Legal Advisor and the

Chief of the Agreed Framework Division, Office of Korean Affairs.

While State generally agreed with the report's conclusions, the

officials provided detailed comments on the presentation and content

of the report. DOE agreed with our findings and conclusions related

to its authorizations of technology transfers to North Korea. We

incorporated the agencies' comments, as well as suggestions for

improving clarity, as appropriate. We sought KEDO's views. However,

a spokesperson for KEDO indicated that KEDO could not provide

comments in the time available.

SCOPE AND METHODOLOGY

------------------------------------------------------------ Letter :9

To obtain information for this report, we reviewed and analyzed the

Agreed Framework; the KEDO and supply agreements; applicable U.S.

laws, regulations, and federal cases; and relevant international

agreements and cases. We also interviewed cognizant officials from

State, DOE, NRC, KEDO, and Combustion Engineering, Inc. (A detailed

description of our work is provided in app. VI.) We conducted our

work from April through September 1996 in accordance with generally

accepted government auditing standards.

---------------------------------------------------------- Letter :9.1

As agreed with your office, we plan no further distribution of this

report until 30 days from the date of this letter. At that time, we

will send copies to the appropriate congressional committees, the

Secretaries of State and Energy, the Executive Director of KEDO, and

other interested parties. We will also make copies available to

others upon request.

If you have any questions, please call me at (202) 512-6543. Major

contributors to this report are listed in appendix VII.

Sincerely yours,

Bernice Steinhardt

Associate Director, Energy,

Resources, and Science Issues

THE CONTENT OF THE AGREED

FRAMEWORK

=========================================================== Appendix I

The Agreed Framework between the United States and the Democratic

People's Republic of Korea (North Korea), dated October 21, 1994,

sets forth a number of actions intended to address the nuclear issue

on the Korean Peninsula. The actions are expressed in the form of

four broad pledges. Specifically, the countries agreed to

-- "cooperate to replace the DPRK's [North Korea's]

graphite-moderated reactors and related facilities with

light-water reactor (LWR) power plants,"

-- "move toward full normalization of political and economic

relations,"

-- "work together for peace and security on a nuclear-free Korean

peninsula," and

-- "work together to strengthen the international nuclear

non-proliferation regime."

The agreement describes each of the broad pledges in further detail.

The first broad pledge describes (1) the United States' agreement to

organize, under its leadership, an international consortium to

finance and supply the reactors and alternative energy to North Korea

and (2) North Korea's reciprocal pledges to, among other things,

freeze its nuclear program.\1 As specified in the agreement, the

arrangements for the reactors and energy will be in accordance with

President Clinton's October 20, 1994, letter to the Supreme Leader of

North Korea. The letter states that the President will use the "full

powers" of his office to facilitate the arrangements for (1)

financing and constructing the reactors and (2) funding and

implementing the supply of interim energy. If the reactors are not

completed or the energy is not provided--for reasons beyond the

control of North Korea--the President agreed to use the "full powers"

of his office, to the extent necessary, to provide both, subject to

the approval of the U.S. Congress. The President conditioned all of

the assurances on North Korea's continued implementation of the

policies described in the Agreed Framework.

In connection with the countries' second broad pledge, the United

States and North Korea agreed to (l) reduce barriers on trade and

investment by January 21, 1995; (2) open liaison offices in each

other's capital following the resolution of consular and other

technical issues; and (3) upgrade bilateral relations to the

ambassadorial level once progress was made on (unspecified) issues of

concern to each side.

For the third pledge, the United States agreed to provide formal

assurances to North Korea against the threat or use of nuclear

weapons by the United States. In return, North Korea agreed to

consistently take steps to implement the North-South Joint

Declaration on the Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula and to

engage in a dialogue with South Korea.\2

Finally, under the last pledge, North Korea agreed to remain a party

to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) and

to allow the implementation of its agreement with the International

Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) for safeguarding its nuclear materials

(nuclear safeguards agreement), as required by the treaty.

Specifically, North Korea agreed--pending the conclusion of the

contract for supplying the reactors and energy--to allow IAEA to

continue the inspections needed for IAEA's continuity of safeguards

at the facilities not subject to the freeze. Once the contract is

concluded, North Korea agreed to allow IAEA to make additional

inspections at these facilities. North Korea also agreed to comply

fully with its IAEA safeguards agreement when a significant portion

of the reactor project is completed but before it receives delivery

of key nuclear reactor components.

--------------------

\1 This section of the agreement also provides details about the

scope of the project. For example, the agreement specifies that the

reactors will have a total generating capacity of approximately

2,000-megawatt electric (MW(e)) and that they will be provided by a

target date of 2003.

\2 North Korea and South Korea signed a "Joint Declaration on the

Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula" on Dec. 31, 1991. Under

the agreement, the parties pledged, among other things, not to (1)

"test, produce, receive, possess, deploy or use nuclear weapons" or

(2) possess nuclear reprocessing and uranium enrichment facilities.

The parties also agreed to allow mutual inspections of their nuclear

facilities subject to procedures to be negotiated between the

parties.

CHRONOLOGY OF KEY EVENTS RELATED

TO THE NORTH KOREAN NUCLEAR ISSUE

========================================================== Appendix II

Mid-1950s\1

North Korea began developing its nuclear program. The rationale for

the program was scientific research and the production of radioactive

isotopes for medical and industrial uses.

1974

North Korea joined IAEA.

1980s

North Korea began operating a 5-MW(e) research reactor and a

"radiochemical laboratory"--North Korea's term for its plutonium

reprocessing plant--in Yongbyon. North Korea also began constructing

two larger reactors--a 50-MW(e) reactor in Yongbyon and a 200-MW(e)

reactor at Taechon.\2

December 1985

North Korea signed the NPT, which, among other things, obligated

North Korea to negotiate an agreement with the IAEA for safeguarding

the nuclear materials in its possession.

1989

North Korea shut down its 5-MW(e) reactor for between 70 to 100 days.

Sources believe that North Korea removed and later reprocessed the

fuel, separating up to 13 kilograms of weapons-grade plutonium usable

for producing nuclear bombs. (The suspected diversion was, among

other things, inferred from a subsequent laboratory analysis of

materials collected during IAEA's inspections that began in 1992.)

1990 and 1991

North Korea ran the 5-MW(e) reactor at low levels for about 30 days

in 1990 and about 50 days in 1991. Such low levels of operation

create the technical possibility that fuel could have been removed

and subsequently reprocessed. However, U.S. experts consider this

unlikely.

April 12, 1991

The Defense Minister for the Republic of Korea (South Korea) stated

that South Korea might launch a commando attack on Yongbyon if North

Korea continued with the construction of the 50-MW(e) reactor there.

Late 1991

The United States withdrew all nuclear weapons from South Korea,

thereby removing one rationale that North Korea had used to delay

signing its safeguards agreement with IAEA.

December 31, 1991

North Korea and South Korea signed a "Joint Declaration on the

Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula." They pledged, among other

things, not to (1) test, produce, receive, possess, deploy or use

nuclear weapons or (2) possess nuclear reprocessing and uranium

enrichment facilities. The parties also agreed to allow mutual

inspections subject to procedures to be negotiated between them.

Early January 1992

High-level officials from the United States and North Korea met to

discuss the range of issues affecting the countries' relations,

including the nuclear issue.

January 30, 1992

North Korea signed a safeguards agreement with IAEA. The agreement

called for IAEA to inspect the nation's nuclear facilities after

ratification by North Korea's legislative body.

April 10, 1992

The IAEA/North Korea safeguards agreement became effective.

May 4, 1992

North Korea submitted its declaration of nuclear materials to IAEA,

as required by IAEA's safeguards agreements. According to the

declaration, North Korea had seven sites and about 90 grams of

plutonium in its possession that were subject to IAEA's inspections.

According to North Korea, the nuclear material resulted from its

reprocessing of 89 defective fuel rods in 1989.

May 1992

IAEA began inspections to verify the correctness and completeness of

North Korea's declaration.\3

July 1992

An IAEA inspection team collected information that subsequently

resulted in the disclosure of discrepancies in North Korea's

declaration of nuclear materials. Instead of reprocessing spent fuel

from 89 damaged fuel rods on just one occasion, IAEA concluded that

North Korea has probably reprocessed spent fuel on three to four

occasions since 1989. Additional inspections revealed further

inconsistencies in North Korea's declaration.

Late 1992

IAEA informally requested that it be given access to two additional

sites--located in the Yongbyon nuclear complex--that it suspected of

housing nuclear waste. North Korea allowed IAEA to visually inspect

one of the sites but denied any access to the other.

February 9, 1993

IAEA invoked the "special inspections clause" of its safeguards

agreement with North Korea, indicating that it wanted to inspect two

sites that North

Korea had not declared and that IAEA suspected had a bearing on the

history of North Korea's nuclear program.

February 1993

North Korea denied IAEA access to the two undeclared sites. North

Korea said that the sites were military installations with no

connection to its nuclear program.

February 22, 1993

At a meeting of the IAEA board, the members were shown U.S. aerial

surveillance photographs and a chemical analysis of data collected by

IAEA inspectors. The evidence reportedly (1) confirmed the existence

of a nuclear waste dump--long denied by North Korea--and (2)

disclosed discrepancies in North Korea's declaration of the nuclear

materials in its possession.

March 12, 1993

North Korea announced its intention to withdraw from the NPT,

effective June 12, 1993. The announcement elevated what was viewed

as a serious proliferation threat into a major diplomatic

confrontation between the United States and North Korea.

April 1, 1993

IAEA declared that North Korea was not adhering to its safeguards

agreement with IAEA and, consequently, that IAEA could no longer

guarantee that North Korea's nuclear material was not being diverted

for nonpeaceful purposes.

April 8, 1993

In a statement to the media, the President of the United Nations

Security Council welcomed all efforts to resolve the impasse that had

arisen between North Korea and IAEA. The President encouraged IAEA

to continue, among other things, its consultations with North Korea

for a proper settlement of the nuclear verification issue.

April 22, 1993

The United States indicated its readiness to participate in

high-level negotiations with North Korea to help resolve the crisis

caused by North Korea's refusal to abide by the NPT. The U.S.

objectives for the talks were to get North Korea to (1) remain in the

NPT and come into compliance with its NPT obligations, which require

full inspections at its nuclear facilities, and (2) carry out its

December 1991 denuclearization accord with South Korea.\4

May 1993

The United Nations Security Council passed a resolution requesting

North Korea (1) to allow IAEA inspections and (2) not to withdraw

from the NPT.

IAEA sent inspectors to (1) verify that there had been no further

diversion of nuclear material and (2) maintain monitoring equipment

that IAEA had previously installed at North Korea's declared nuclear

facilities.

June 2-11, 1993

The United States and North Korea held their first round of

high-level talks in New York. On June 11, 1993, hours before North

Korea's withdrawal from the NPT would have become effective, the

United States and North Korea issued a joint statement in which North

Korea agreed to "suspend" its withdrawal from the NPT for as long as

it "considers necessary." North Korea also agreed to the full and

impartial application of IAEA's safeguards. The United States

granted assurances against the threat and use of force, including

nuclear weapons, and a promise of "non-interference" in North Korea's

internal affairs. The United States subsequently stated that (1)

North Korea must accept IAEA inspections to ensure the continuity of

the safeguards, (2) forgo reprocessing, and (3) allow IAEA to be

present when it refueled its 5-MW(e) reactor.

July 1993

Speaking before U.S. military forces deployed in South Korea,

President Clinton reportedly said that if North Korea developed and

used nuclear,

weapons, "we would quickly and overwhelmingly retaliate. It would

mean the end of their country as they know it."

July 14-19, 1993

The U.S. and North Korean delegations held a second round of

high-level negotiations in Geneva, Switzerland. Both sides

reaffirmed the principles of the June 11, 1993, joint statement. As

part of the final resolution of the nuclear issue, the United States

said that it was willing to explore options for replacing North

Korea's graphite-moderated reactors and related facilities with

light-water reactors.

August 1993

North Korea limited the operations of an IAEA inspection team that

had been sent to (1) replace film and batteries in cameras and (2)

check seals installed by IAEA in 1992. North Korea reportedly

required that the team work at night with flashlights.

Fall 1993

IAEA requested North Korea to allow greater access to its facilities.

North Korea denied the request. In reaction to North Korea's rebuffs

of the IAEA, the United States refused to schedule a third

negotiating session with North Korea. Instead, North Korean and U.S.

officials held low-level meetings at the United Nations in October

and November 1993.

Early November 1993

IAEA's Director General delivered a report to the United Nations

which stated that if IAEA inspectors were not permitted to revisit

North Korea's nuclear facilities, IAEA could no longer verify the

IAEA/North Korea safeguards agreement.

November 1993

On November 11, 1993, North Korea proposed that the United States and

North Korea negotiate a "package solution" to the nuclear weapons

issue. The United States subsequently accepted North Korea's

proposal in principle. However, the United States required that

North Korea, among other things, allow IAEA full access to North

Korea's seven declared facilities so that IAEA could maintain its

"continuity of safeguards."

December 3, 1993

In mid-level talks at the United Nations, North Korea offered to

restore IAEA's access to five of its declared sites so that IAEA

could change the film and batteries in the cameras monitoring North

Korea's activities at the sites.

Late 1993

The U.S. Central Intelligence Agency and the Defense Intelligence

Agency estimated that North Korea had separated about 12 kilograms of

plutonium--enough for one to two nuclear bombs.\5

December 1993

IAEA's Director General warned that safeguards on North Korea's

declared installations and materials could no longer provide a

meaningful assurance of peaceful use. However, he said that the

integrity of IAEA's safeguards could be restored if inspections were

reinstated.

December 29, 1993

North Korea and the United States reached a tentative understanding

about IAEA's inspections of North Korea's declared facilities.

Sources indicate that the understanding shifted negotiations toward

talks between North Korea and the IAEA.

Early January 1994

North Korea announced that IAEA inspectors would be allowed to visit

all seven of its declared nuclear facilities. (The two suspected--

undeclared--sites were still off-limits.) North Korea justified the

limited inspections on the basis that its action to withdraw from the

NPT in June 1993 had exempted it from the inspection requirements

applicable to other NPT members.

January 1994

The Director of the Central Intelligence Agency estimated that North

Korea may have produced one or two nuclear weapons.\6

Early 1994

North Korea and IAEA conducted negotiations on the details of IAEA's

inspections pursuant to the December 29, 1993, "tentative" U.S./North

Korean understanding.

Late January 1994

The United States announced that it would deploy additional Patriot

missile batteries, Apache helicopters, and advanced counter-artillery

radar in South Korea.

February 15, 1994

North Korea agreed in writing to a limited inspection of all of its

declared nuclear sites in accordance with a checklist of procedures

prepared by IAEA.\7 The checklist specified that IAEA would, among

other things, take samples from a "glove box" connected to the

reprocessing facility and perform gamma ray scans of the facility.

According to IAEA, the procedures were needed to restore IAEA's

continuity of knowledge at the declared sites.

February 25, 1994

The United States and North Korea issued a statement, entitled

"Agreed Conclusions," which specified, among other things, that the

inspections would proceed consistent with the timing and manner

agreed to between North Korea and IAEA on February 15, 1994. The

statement also announced U.S./North Korean intentions to begin a

third round of negotiations in March 1994.\8

March 3-14, 1994

IAEA resumed inspections. The inspectors proceeded without incident

at several locations but encountered problems at the reprocessing

plant, where they were precluded from (1) entering certain portions

of the plant and (2) performing activities--such as taking samples

from reprocessing equipment and conducting a gamma ray scan of the

reprocessing facility--that North Korea had agreed to on February 15,

1994.\9

March 15, 1994

IAEA terminated inspections after North Korea barred the inspectors

from taking samples at key locations in its plutonium reprocessing

plant. The March 1994 inspection reportedly indicated that North

Korea had (1) resumed construction on the second reprocessing line in

the facility, (2) constructed new connections between the old and new

reprocessing lines, and (3) broken seals on previously tagged

reprocessing equipment.

March 20, 1994

The United States announced that it would not participate in the

third round of U.S./North Korean high-level negotiations scheduled

for March 1994. Instead, the United States said it would refer the

results of the aborted IAEA inspection to the United Nations Security

Council for action.

March 21, 1994

IAEA indicated, once again, that it could no longer ensure that North

Korea's nuclear materials were not being diverted for nonpeaceful

purposes.

March 30, 1994

The U.S. Secretary of Defense warned publicly that the United States

intended to stop North Korea from developing a substantial arsenal of

nuclear weapons, even at the cost of another war on the Korean

Peninsula.

Early April 1994

The United Nations Security Council decided to request that North

Korea allow IAEA to complete its inspections.

April 4, 1994

President Clinton ordered the establishment of a Senior Policy

Steering Group on Korea to coordinate all aspects of the U.S. policy

on the nuclear issue on the Korean Peninsula.

May 3, 1994

President Clinton publicly offered a "hand of friendship" to North

Korea if it pledged not to develop nuclear weapons. In a speech to

the National Press Club, the U.S. Secretary of Defense outlined the

two choices available to North Korea: continue its nuclear program

and face the consequences--including the possibility of war--or drop

the program and accept economic aid and normal relations with the

United States and its allies.

Mid-May 1994

Workers began removing the spent fuel from the 5-MW(e) reactor in

violation of North Korea's safeguards agreement with IAEA and IAEA's

previous instructions informing North Korea that IAEA inspectors

would need to sample, segregate, and monitor the fuel rods to

preserve evidence of past plutonium production. North Korea refused

to comply but allowed two inspectors to watch the fuel-removal

process. IAEA informed North Korea that the removal of fuel without

proper safeguards constituted "a serious violation" of the safeguards

agreement.

The United States offered to hold the long-deferred third series of

high-level talks to consider the entire range of issues related to

the Korean peninsula, including the economic, diplomatic, and other

benefits that North Korea could receive in return for reversing its

decision to withdraw from the NPT. The talks were conditioned on

North Korea's willingness to allow IAEA to monitor the refueling

operation and to safeguard the fuel rods already removed.

May 21, 1994

North Korea agreed to meet with IAEA inspectors to discuss ways to

preserve the fuel rods that North Korea was removing from its 5-MW(e)

reactor in order to permit a future assessment of the reactor's

operating history.

End of May 1994

North Korea rejected IAEA's proposal for preserving the fuel rods.

South Korea responded by putting its military on a higher state of

alert.

May 28, 1994

Following a failure of negotiations aimed at subjecting the refueling

operation to international safeguards, IAEA's Director General

reported to the United Nations Secretary General that the agency was

quickly losing its ability to verify the amount of North Korea's past

production of plutonium.

May 30, 1994

The President of the United Nations Security Council, on behalf of

the Council members, urged North Korea "to proceed with the discharge

operations at the five megawatt [5-MW(e)] reactor in a manner which

preserves the technical possibility of fuel measurements, in

accordance with IAEA's requirements." In deference to China, the

statement did not include a direct threat of economic sanctions.

June 3, 1994

IAEA's Director General told the United Nations Security Council that

North Korea had removed all but 1,800 of the 8,000 fuel rods in the

5-MW(e) reactor and that by mixing them up, North Korea had made it

impossible to reconstruct the operating history of the reactor.

Early June 1994

IAEA members voted to exempt North Korea from receiving IAEA

technical assistance--a benefit accorded IAEA members. North Korea

responded by quitting IAEA and threatening to expel the IAEA

inspectors.\10

The United States announced that it intended to pursue global

economic sanctions against North Korea if it did not allow IAEA

inspectors to examine the spent fuel rods removed from the 5-MW(e)

reactor in Yongbyon. North Korea responded that it would treat such

sanctions as an act of war.

June 5, 1994

The Secretary of Defense confirmed that the United States had built

up its troops in South Korea.

June 15, 1994

The U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations announced that the United

States would begin consultations with other countries to implement

sanctions against North Korea.

June 15-18, 1994

Former President Carter visited Pyongyang, North Korea. While there,

Kim Il Sung--the North Korean leader at that time--offered to freeze

North Korea's nuclear program in return for the resumption of

high-level talks between the United States and North Korea. Under

the proposal, IAEA would be allowed to (1) monitor the fuel rods in

the spent fuel pond and (2) engage in some routine monitoring of

North Korea's other nuclear facilities to maintain IAEA's continuity

of safeguards at the sites. However, the issue of North Korea's past

production of plutonium would be deferred.

June 21, 1994

The United States offered to (1) resume high-level talks with North

Korea and (2) suspend its efforts to have the United Nations impose

sanctions on North Korea once the talks were under way. At about the

same time, North Korea took steps to follow up on pledges it had made

to former President Carter. Specifically, North Korea extended the

visas for IAEA inspectors and proposed a date for a summit with South

Korea.

June 27, 1994

The United States and North Korea announced that their negotiations

would resume on July 8, 1994.

July 8-10, 1994

The United States and North Korea began a third round of negotiations

to discuss, among other things, a proposal by the North Korean leader

to freeze North Korea's nuclear program. The negotiations--held in

Geneva--terminated prematurely because of the death of North Korea's

leader on July 8, 1994.

August 5-14, 1994

The United States and North Korea resumed the Geneva negotiations

interrupted by the death of Kim Il Sung. The negotiations reportedly

explored North Korea's willingness to abandon its graphite-moderated

reactors in return for a U.S. commitment to, among other things,

make arrangements for supplying North Korea with light-water

reactors.

August 12, 1994

The United States and North Korea issued an "Agreed Statement"

describing "elements [that] should be part of a final resolution of

the nuclear issue" in North Korea, including (1) a freeze on North

Korea's nuclear program in exchange for light-water reactors and

interim energy supplies and (2) movement toward the full

normalization of political and economic relations.

September 10, 1994

The United States and North Korea held simultaneous working-level

meetings in Berlin and Pyongyang to discuss plans for replacing North

Korea's reactors with light-water reactors and establishing liaison

offices in each other's capitals.

September 23, 1994

The third round of high-level negotiations between the United States

and North Korea resumed in Geneva.

October 21, 1994

The United States and North Korea concluded the "Agreed Framework,"

an agreement intended to produce an overall settlement of the nuclear

issue on the Korean Peninsula. In conjunction, the United States

provided an October 20, 1994, letter from President Clinton to Kim

Jong Il--the Supreme Leader of North Korea. The letter stated, among

other things, that the President would use "the full powers" of his

office to facilitate the arrangements for the financing and

construction of the light-water reactor project and for the funding

and implementation of interim energy supplies. (See app. I for

information about the (1) agreement's content and (2) President's

letter to the Supreme Leader of North Korea.)

--------------------

\1 The following chronology was compiled primarily from Congressional

Research Service reports and briefs and journal articles. The

chronology is included to describe the key events preceding the

Agreed Framework. We attempted to reconcile inconsistencies between

the sources; however, we did not independently verify the information

in this appendix. Further, while the State Department provided

comments on a draft of this report, State did not take a position

about the accuracy of the text.

\2 The existing 5-MW(e) reactor is thought to be capable of producing

about 7 kilograms of plutonium annually. When completed, the two

reactors under construction were expected to produce about 200

kilograms of plutonium annually.

\3 IAEA conducted numerous inspections to verify the completeness of

North Korea's declaration between about mid-1992 and early 1993.

IAEA inspectors also placed seals and other safeguards on equipment

and buildings at North Korea's declared nuclear sites.

\4 The move followed South Korea's Apr. 15, 1993, decision to allow

U.S./North Korean negotiations. (Prior to that time, the United

States and South Korea had insisted upon negotiations between North