Nuclear Nonproliferation: Status of U.S. Efforts to Improve Nuclear Material Controls in Newly Independent States

(Chapter Report, 03/08/96, GAO/NSIAD/RCED-96-89)

Pursuant to a congressional request, GAO reviewed U.S. efforts to

strengthen controls over nuclear materials in the newly independent

states (NIS) of the former Soviet Union, focusing on the: (1) nature and

extent of problems with controlling direct-use nuclear materials in NIS;

(2) status and future prospects of U.S. efforts in Russia, Ukraine,

Kazakhstan, and Belarus; and (3) executive branch's consolidation of

U.S. efforts in the Department of Energy (DOE).

GAO found that: (1) of the 1,400 metric tons of nuclear material that

the former Soviet Union produced, much is not related to the nuclear

weapons industry; (2) this material is extremely vulnerable to theft and

diversion because it has not been have accurately and completely

inventoried, NIS do not have adequate resources to track its movement,

it is relatively safe and easy to handle, and economic and social

upheavals have increased its value; (3) the amount of nuclear material

available is expected to increase as Russia dismantles its nuclear

weapons; (4) seizures of small quantities of these stolen materials have

happened only by chance; (5) the Department of Defense's threat

reduction program has gained momentum at NIS facilities and Russia has

agreed to upgrade controls at high-priority sites and develop a national

material protection control and accounting (MPC&A) regulatory

infrastructure; (6) DOE lab-to-lab programs have improved controls at

two Russian labs and begun providing monitors to several Russian weapons

facilities; (7) the United States plans to expand its MPC&A assistance

program in 1996 to all known NIS direct-use nuclear facilities and has

consolidated management and funding for most programs in DOE; (8)

inherent uncertainties regarding costs and verification abilities could

affect the expanded program's success; and (9) DOE is developing a

long-range plan to improve the MPC&A systems in all facilities handling

direct-use material by the year 2002, consolidate program plans, and

develop a centralized cost-reporting system and a flexible audit

approach.

--------------------------- Indexing Terms -----------------------------

REPORTNUM: NSIAD/RCED-96-89

TITLE: Nuclear Nonproliferation: Status of U.S. Efforts to Improve

Nuclear Material Controls in Newly Independent

States

DATE: 03/08/96

SUBJECT: Nuclear waste disposal

Nuclear facility security

Dual-use technologies

International agreements

Foreign governments

Nuclear proliferation

International cooperation

Larceny

Federal aid to foreign countries

Inventory control

IDENTIFIER: Soviet Union

Russia

Ukraine

Kazakhstan

Belarus

DOD Cooperative Threat Reduction Program

DOD CTR Government-to-Government Program

DOE Lab-to-Lab Nuclear Material Control Program

Commonwealth of Independent States

Project Sapphire

******************************************************************

** This file contains an ASCII representation of the text of a **

** GAO report. Delineations within the text indicating chapter **

** titles, headings, and bullets are preserved. Major **

** divisions and subdivisions of the text, such as Chapters, **

** Sections, and Appendixes, are identified by double and **

** single lines. The numbers on the right end of these lines **

** indicate the position of each of the subsections in the **

** document outline. These numbers do NOT correspond with the **

** page numbers of the printed product. **

** **

** No attempt has been made to display graphic images, although **

** figure captions are reproduced. Tables are included, but **

** may not resemble those in the printed version. **

** **

** Please see the PDF (Portable Document Format) file, when **

** available, for a complete electronic file of the printed **

** document's contents. **

** **

** A printed copy of this report may be obtained from the GAO **

** Document Distribution Center. For further details, please **

** send an e-mail message to: **

** **

** <info@www.gao.gov> **

** **

** with the message 'info' in the body. **

******************************************************************

Cover

================================================================ COVER

Report to Congressional Requesters

March 1996

NUCLEAR NONPROLIFERATION - STATUS

OF U.S. EFFORTS TO IMPROVE

NUCLEAR MATERIAL CONTROLS IN NEWLY

INDEPENDENT STATES

GAO/NSIAD/RCED-96-89

Nuclear Nonproliferation

(711098)(170262)

Abbreviations

=============================================================== ABBREV

CTR - Cooperative Threat Reduction

DOD - Department of Defense

DOE - Department of Energy

GAN - Gosatomnadzor

HEU - highly enriched uranium

KGB - Komityet Gosudarstvyennoj Byezopasnosti

MPC&A - material protection control and accounting

MINATOM - Russian Ministry of Atomic Energy

NIS - newly independent states

Letter

=============================================================== LETTER

B-270052

March 8, 1996

The Honorable Sam Nunn

Ranking Minority Member

Permanent Subcommittee

on Investigations

Committee on Governmental Affairs

United States Senate

The Honorable Floyd D. Spence

Chairman

The Honorable Ronald V. Dellums

Ranking Minority Member

Committee on National Security

House of Representatives

This report responds to your request that we review U.S. efforts to

strengthen controls over nuclear material in the newly independent

states of the former Soviet Union. As requested, unless you publicly

announce its contents earlier, we plan no further distribution of

this report until 30 days after its issue date. At that time, we

will send copies to the Secretaries of State, Defense, and Energy;

and the Chairman of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. We will also

make copies available to other interested parties on request.

If you have any questions concerning this report, we can be reached

at (202) 512-4128 and (202) 512-3841, respectively. Major

contributors to this report are listed in appendix III.

Harold J. Johnson

Associate Director, International

Relations and Trade Issues

National Security and International

Affairs Division

Victor S. Rezendes

Director, Energy, Resources, and

Science Issues

Resources, Community and

Economic Development Division

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

============================================================ Chapter 0

PURPOSE

---------------------------------------------------------- Chapter 0:1

Safeguarding nuclear material that can be used directly in nuclear

explosives has become a primary national security concern for the

United States and the newly independent states of the former Soviet

Union. Terrorists and countries seeking nuclear weapons could use as

little as

25 kilograms of highly enriched uranium (HEU) or 8 kilograms of

plutonium to build a nuclear explosive. The seizure of HEU and

plutonium in Europe and Russia has prompted concerns about how the

newly independent states control their direct-use materials. The

Ranking Minority Member of the Permanent Subcommittee on

Investigations, Senate Governmental Affairs Committee, and the

Chairman and Ranking Minority Member of the House Committee on

National Security requested that GAO review U.S. efforts to help the

newly independent states strengthen their nuclear material controls.

GAO's report addresses (1) the nature and extent of problems with

controlling direct-use nuclear materials in the newly independent

states; (2) the status and future prospects of U.S. efforts to help

strengthen controls in Russia, Ukraine, Kazakstan, and Belarus; and

(3) the executive branch's consolidation of U.S. efforts in the

Department of Energy (DOE). The scope of GAO's review included

direct-use nuclear material controlled by civilian authorities in the

newly independent states and direct-use material used for naval

nuclear propulsion purposes. GAO did not review the protection,

control, and accounting systems used for nuclear weapons in the

possession of the Ministry of Defense in Russia. U.S. officials

believe there to be relatively better controls over weapons in the

custody of the Ministry of Defense than over material outside of

weapons.\1 GAO recently issued a report that addressed the safety of

nuclear facilities in the newly independent states.\2

--------------------

\1 The Department of Defense (DOD) has an ongoing program with the

Russian Ministry of Defense to enhance the security of nuclear

weapons in Ministry of Defense custody during transportation and

storage.

\2 See Nuclear Safety: Concerns With Nuclear Facilities and Other

Sources of Radiation in the Former Soviet Union (GAO/RCED-96-4 Nov.

7, 1995).

BACKGROUND

---------------------------------------------------------- Chapter 0:2

"Direct-use nuclear material" consists of HEU and plutonium that is

relatively easy to handle because it has not been exposed to

radiation or has been separated from highly radioactive materials.\3

Direct-use material presents a high proliferation risk because it can

be used to manufacture a nuclear weapon without further enrichment or

irradiation in a reactor. Many types of nuclear facilities routinely

handle, process, or store such direct-use materials. Direct-use

material can be found at research reactors, reactor fuel fabrication

facilities, uranium enrichment plants, spent fuel reprocessing

facilities, and nuclear material storage sites, as well as nuclear

weapons production facilities. Material protection, control, and

accounting (MPC&A) systems are used at such facilities to deter,

detect, and respond to attempted thefts.

The United States is pursuing two different, but complementary

strategies to achieve its goals of rapidly improving nuclear material

controls over direct-use material in the newly independent states: a

government- to-government program, and an initiative known as the

lab-to-lab program.\4 Under the government-to-government program,

initially sponsored and funded by the Department of Defense

Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR) program,\5 the United States

agreed in 1993 to work directly with the governments of Russia,

Ukraine, and Kazakstan to develop national MPC&A systems and improve

controls over civilian nuclear material. The United States extended

such assistance to Belarus in 1995. Although CTR funds were used,

DOE was responsible for implementing the program. In April 1994, DOE

initiated the lab-to-lab program to work directly with Russian

nuclear facilities in improving their MPC&A systems. The program is

limited to Russia and intended to rapidly improve controls at

civilian research, naval nuclear propulsion, and civilian-controlled,

nuclear weapons-related facilities. This program is funded jointly

by DOE and the CTR program.\6

--------------------

\3 HEU is uranium enriched above 20 percent in the isotope uranium

235. An isotope is a variation of a chemical element.

\4 The government-to-government program is implemented through formal

agreements that establish, among other things, rights to audit and

examination by U.S. officials. The lab-to-lab program works

directly with Russian nuclear facilities and is not bound by the

formal agreements. To the maximum extent feasible, the

government-to-government programs are required to use U.S. goods and

services, while the lab-to-lab program can purchase goods and

services from other suppliers as needed.

\5 Congress established the CTR program in 1991 to help Russia,

Ukraine, Kazakstan, and Belarus safely store, transport, and destroy

weapons of mass destruction and prevent their proliferation. See

Weapons of Mass Destruction: Helping the Former Soviet Union Reduce

the Threat: An Update (GAO/NSIAD-95-165, June 9, 1995).

\6 DOE is also providing assistance to upgrade four facilities that

are not included in the lab-to-lab program. These facilities are

located in Georgia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Uzbekistan.

RESULTS IN BRIEF

---------------------------------------------------------- Chapter 0:3

The Soviet Union produced approximately 1,200 metric tons of HEU and

200 metric tons of plutonium. Much of this material is outside of

nuclear weapons, is highly attractive to theft, and the newly

independent states may not have accurate and complete inventories of

the material they inherited. Social and economic changes in the

newly independent states have increased the threat of theft and

diversion of nuclear material, and with the breakdown of Soviet-era

MPC&A systems, the newly independent states may not be as able to

counter the increased threat. Nuclear facilities rely on antiquated

accounting systems that cannot quickly detect and localize nuclear

material losses. Many facilities lack modern equipment that can

detect unauthorized attempts to remove nuclear material from

facilities. While as yet there is no direct evidence that a black

market for stolen or diverted nuclear material exists in the newly

independent states, the seizures of direct-use material in Russia and

Europe have increased concerns about theft and diversion.

U.S. efforts to help the newly independent states improve their

MPC&A systems for direct-use material had a slow start, but are now

gaining momentum. DOD's government-to-government CTR program

obligated $59 million and spent about $4 million from fiscal years

1991 to 1995 for MPC&A improvements in Russia, Ukraine, Kazakstan,

and Belarus. The program has provided working group meetings, site

surveys, physical protection equipment, computers, and training for

projects in Russia, Ukraine, Kazakstan, and Belarus. Initially, the

program was slow because (1) until January 1995, the Russian Ministry

of Atomic Energy (MINATOM) had refused access to Russian direct-use

facilities and (2) CTR-sponsored projects at facilities with

direct-use materials in Ukraine, Kazakstan, and Belarus were just

getting underway. According to DOD officials, program requirements

for using U.S. goods and services and for audits and examinations

also delayed implementation. The program began to gain momentum in

January 1995 when CTR program and MINATOM officials agreed to upgrade

nuclear material controls at five high-priority facilities handling

direct-use material.\6 DOE and Russia's nuclear regulatory agency

have also agreed to cooperate on the development of a national MPC&A

regulatory infrastructure.

DOE's lab-to-lab program obligated $17 million and spent $14 million

in fiscal years 1994 and 1995. This program has improved controls at

two "zero-power" research reactors, and begun providing nuclear

material monitors to several MINATOM defense facilities to help them

detect unauthorized attempts to remove direct-use material.\7 In

fiscal year 1996, the program is implementing additional projects in

MINATOM's nuclear defense complex.

In fiscal year 1996, the United States expanded the MPC&A assistance

program to include all known facilities with direct-use material

outside of weapons in the newly independent states. Management and

funding for the expanded program were consolidated within DOE. DOE

plans to request from Congress $400 million over 7 years for the

program. However, the expanded program faces several inherent

uncertainties involving its overall costs and U.S. ability to verify

that assistance is being used as intended. DOE is responding to

these uncertainties by developing a long-term plan and a centralized

cost reporting system and by implementing a flexible audit and

examination program.

--------------------

\6 Subsequent to the conclusion of GAO's review, DOE and MINATOM

agreed to add four additional sites to the government-to-government

program and two additional sites to the lab-to-lab program.

\7 A zero-power research reactor is a type of research reactor using

fuel that is not very radioactive.

PRINCIPAL FINDINGS

---------------------------------------------------------- Chapter 0:4

NATURE AND EXTENT OF THE

PROBLEM

-------------------------------------------------------- Chapter 0:4.1

Much of the 1,200 metric tons of highly enriched uranium and 200

metric tons of plutonium produced by the Soviet Union is outside of

nuclear weapons; this stockpile of material is expected to grow

rapidly as Russia proceeds to dismantle its nuclear weapons.

According to DOE, this material is located at 80 to 100 civilian

research, naval nuclear propulsion, and civilian controlled nuclear

weapons-related facilities. It is considered to be highly attractive

to theft because it is (1) not very radioactive and is therefore

relatively safe to handle and (2) in forms that make it readily

accessible to theft, such as items stored in containers that can

easily be carried by one or two persons, or in components from

dismantled weapons.

Nuclear materials in the newly independent states are more vulnerable

to theft and diversion than in the past. Soviet-era control systems

relied heavily on (1) keeping nuclear material in secret cities and

facilities, (2) closely monitoring nuclear industry personnel, and

(3) severely punishing control violations. Closed borders and the

absence of a black market for nuclear material also lessened the

threat of diversion. Without the secrecy and heavy security of the

Soviet system, facilities in the newly independent states must now

rely to a greater degree on other control systems such as manual,

paper-based tracking systems--which cannot quickly locate and assess

material losses--and on labor-intensive physical protection systems

that lack monitors for detecting attempts to steal nuclear material

from a facility. In addition, the newly independent states may not

have complete and accurate inventories of their nuclear materials

because the Soviet Union did not conduct complete and comprehensive

physical inventories at their nuclear facilities. Some of the

facilities GAO visited in March 1995 did not have a comprehensive

inventory of their nuclear materials on hand.

INITIAL EFFORTS TO IMPROVE

CONTROL SYSTEMS IN THE NEWLY

INDEPENDENT STATES HAD A

SLOW START

-------------------------------------------------------- Chapter 0:4.2

Until January 1995, MINATOM refused to grant CTR technical experts

access to direct-use facilities, limiting the program's efforts to a

low-enriched uranium fuel fabrication line. This obstacle was

removed in January 1995 when MINATOM agreed to allow access to five

facilities with direct-use material. In July 1995, the CTR-sponsored

program made progress in controlling direct-use material by

installing physical protection equipment and providing training at a

MINATOM facility that includes an HEU fuel fabrication line. The

Kazakstani, Ukrainian, and Belarussian governments have been more

willing to allow the United States to help upgrade MPC&A systems at

their direct-use material facilities. However, CTR-sponsored

projects in these countries are just beginning, and improvements to

controls over their direct-use materials will not be completed until

the middle of 1996 at the earliest.

Working directly with institutes and operating facilities, DOE's

lab-to-lab program has completed the first phase of an MPC&A project

at a MINATOM zero-power research reactor that will eventually

computerize its inventory system for thousands of kilograms of

direct-use material and upgrade its MPC&A systems. DOE's program has

also upgraded controls at a zero-power research reactor in Moscow

containing about 80 kilograms of direct-use material by (1)

increasing physical protection for the reactor building, (2)

implementing a computerized material accounting system, and (3)

installing access control equipment. The lab-to-lab program has also

deployed nuclear material monitors at three MINATOM nuclear weapons

facilities and two civilian research facilities. Additional monitors

were being shipped as GAO concluded its review.

UNITED STATES EXPANDS MPC&A

ASSISTANCE

-------------------------------------------------------- Chapter 0:4.3

The executive branch has decided to consolidate MPC&A assistance in

DOE. In September 1995, the President directed DOE to develop a

long-range plan to improve MPC&A systems at all facilities in the

newly independent states handling direct-use material by the year

2002. The President also transferred funding and management

responsibilities for the CTR MPC&A program from DOD to DOE in fiscal

year 1996. However, DOE faces several inherent uncertainties in

managing an expanded assistance program over the next 7 years. For

example, while DOE estimates that the program will require $400

million to upgrade 80 facilities with direct-use material, it faces

uncertainties in both the number of facilities to be covered (which

could range to more than 100) and the cost per facility (ranging from

$5 million to $10 million per facility). Because of these

uncertainties, program costs could range from $400 million to over $1

billion. In addition, DOE's ability to directly assess program

progress and confirm that U.S. assistance is used for its intended

purposes may be limited because the Russians may limit the measures

that can be used for these purposes at highly sensitive facilities.

DOE IS RESPONDING TO PROGRAM

UNCERTAINTIES

-------------------------------------------------------- Chapter 0:4.4

DOE is taking steps to ensure that the program is successful and that

U.S. funds are well spent.

DOE is developing a long-term plan for the expanded program that

consolidates the program plans for the government-to-government

and lab-to-lab programs. According to DOE, the plan establishes

objectives, priorities, and timetables for implementing projects

at the 80 to

100 facilities in the newly independent states. DOE has drafted

the plan; however, the plan had not been issued at the time GAO

concluded its review in January 1996.

DOE is developing a consolidated centralized program cost-reporting

system intended to provide DOE with current financial status for

government-to-government and lab-to-lab projects. The

information should be useful in responding to changing budgetary

requirements for the program.

DOE is implementing a flexible audit and program evaluation

approach to provide some assurances that assistance is used only

for its intended purposes. Under the approach, the United

States will pay Russian laboratories for services and equipment

upon completion of clearly defined delivered products and will

use a series of direct and indirect measures to evaluate program

progress and effectiveness. DOE expects to issue a report on

assurances obtained by the lab-to-lab program in March 1996.

RECOMMENDATIONS

---------------------------------------------------------- Chapter 0:5

GAO is making no recommendations in this report.

AGENCY COMMENTS

---------------------------------------------------------- Chapter 0:6

In commenting on this report, the Departments of Energy and State

generally agreed with GAO's assessment of the U.S. effort to improve

nuclear material controls in the newly independent states. The

Department of State offered additional editorial comments that have

been incorporated into the report where appropriate. DOD officials

also agreed with the facts as presented in this report, but expressed

concern about how the report portrays the relative success of the

government-to-government and lab-to-lab programs. These officials

stated that the programs are complementary approaches to achieving

the goal of improving controls and accountability over direct-use

nuclear material in the newly independent states. GAO agrees and has

modified the report accordingly.

INTRODUCTION

============================================================ Chapter 1

Direct-use nuclear material is essential for building nuclear

weapons. The diversion or theft of such material can enable

terrorists or countries to build nuclear weapons without investing in

expensive nuclear technologies and facilities. One way of deterring

and detecting theft is by instituting nuclear material control

systems on a national level and at facilities handling direct-use

material.

WHAT IS DIRECT-USE MATERIAL?

---------------------------------------------------------- Chapter 1:1

"Direct-use nuclear material" consists of highly enriched uranium

(HEU) and plutonium that is relatively easy to handle because it has

not been exposed to radiation or has been separated from highly

radioactive materials.\1 Direct-use material presents a high

proliferation risk because it can be used to manufacture a nuclear

weapon without further enrichment or irradiation in a reactor.

According to the International Atomic Energy Agency, approximately 25

kilograms of HEU or 8 kilograms of plutonium is needed to manufacture

a nuclear explosive, although the Department of Energy (DOE) suggests

the amounts needed to build a weapon may be smaller.

Many types of nuclear facilities routinely handle, process, or store

direct-use material. Besides nuclear weapon production facilities,

direct-use material can also be found at research reactors, reactor

fuel fabrication facilities, uranium enrichment plants, spent fuel

reprocessing facilities, and nuclear material storage sites. Most

civilian nuclear power facilities are of less concern because they

use low-enriched or natural uranium as fuel, which would require

additional enrichment before the fuel would be suitable for nuclear

weapons. While these reactors produce plutonium in spent reactor

fuel, such fuel is dangerous to handle because it is highly

radioactive. Spent reactor fuel also requires reprocessing before it

is suitable for nuclear weapons.

--------------------

\1 HEU is uranium enriched above 20 percent in the isotope uranium

235. An isotope is a variation of a chemical element.

HOW IS NUCLEAR MATERIAL

CONTROLLED?

---------------------------------------------------------- Chapter 1:2

Nuclear materials are controlled to prevent and detect their theft.

Nuclear material can be stolen or diverted by (1) outside individuals

or groups, such as terrorists attempting to break in and steal

nuclear material; (2) inside individuals or groups, such as one or

more employees that have access to nuclear material; and (3)

combinations of insiders and outsiders.

A nuclear material control system consists of three overlapping

components--material protection, material control, and material

accounting. Together they compose a set of procedures, personnel,

and equipment that address both insider and outsider threats.

Material protection systems are designed to limit access to nuclear

material by outside individuals and prevent the unauthorized removal

of material from a facility by inside individuals. Nuclear

facilities protect their material by (1) installing fences with

sensors and television cameras to delay, detect, and assess

unauthorized intrusions; (2) posting armed guards at entry and exit

points; (3) establishing a protective response force that can react

to unauthorized intrusions; and (4) installing nuclear material

monitors to detect attempts to remove material from a facility.

Nuclear facilities also assess the reliability of personnel with

access to nuclear material by conducting background checks and

continuously monitoring their behavior.

Material control systems contain, monitor, and establish custody over

nuclear material. Nuclear facilities control material by (1) storing

material in containers and vaults equipped with seals that can

indicate when tampering may have occurred, (2) controlling access to

and exit from nuclear material areas using badge and personnel

identification equipment, and (3) establishing procedures to closely

monitor nuclear materials.\2 Nuclear facilities also designate

custodians to be responsible for nuclear material in their

possession.

Material accounting systems maintain information on the quantity of

nuclear materials within specified areas and on transfers in and out

of those areas. They employ periodic inventories to count and

measure nuclear material by element and isotopic content. Nuclear

facilities use the inventory and transfer data to establish nuclear

material balances, which track materials on hand and the flow of

material within a specified area. The material balances are closed

periodically by reconciling physical inventory with recorded

inventories, correcting errors, calculating inventory differences and

evaluating their statistical differences, and performing trend

analysis to detect protracted theft of nuclear material. Nuclear

facilities in the United States are capable of updating material

accounting data within 24-hour periods. Some U.S. facilities with

more modern nuclear accounting systems are capable of updating

material accounting data within 4 hours.

In addition to facility systems, the United States and most other

countries have established national material protection, control, and

accounting (MPC&A) systems. These systems include regulations

governing procedures for nuclear material protection control and

accounting, inspection requirements to ensure that the systems are

implemented properly, and tracking systems to provide information on

the location and disposition of nuclear material nationally. In the

United States, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission and DOE have

promulgated regulations on controlling nuclear material.

--------------------

\2 One such procedure is to require two or more authorized persons to

be present when nuclear material is accessed. Another procedure is

to use closely monitored television cameras to maintain surveillance

over nuclear material.

HOW IS THE UNITED STATES

ASSISTING THE NEWLY INDEPENDENT

STATES TO IMPROVE THEIR NUCLEAR

MATERIAL CONTROLS?

---------------------------------------------------------- Chapter 1:3

The United States is pursuing two different, but complementary

strategies to achieve its goals of rapidly improving nuclear material

controls over direct-use material in the newly independent states

(NIS).\3 Under the Cooperative Threat Reduction (CTR) program,the

U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) entered into agreements with the

governments of Russia, Ukraine, and Kazakstan in 1993 to rapidly

improve nuclear material controls over civilian nuclear material and

develop national MPC&A systems in these countries. On June 23, 1995,

DOD entered into an agreement with the Ministry of Defense in Belarus

to improve controls over its civilian nuclear material. DOE

implements the programs under these agreements.\4

As a complementing strategy, DOE initiated a program in April 1994 of

MPC&A cooperation with Russia's nuclear institutes, operating

facilities, and enterprises. This initiative, known as the

lab-to-lab program, brings U.S. and Russian laboratory personnel

directly together to work cooperatively on implementing MPC&A

upgrades at Russian nuclear facilities. The purpose of the

lab-to-lab program is to rapidly improve MPC&A at civilian, naval

nuclear, and nuclear weapons-related facilities handling direct-use

material in Russia. The program is jointly funded by DOE and the CTR

program.

--------------------

\3 Other related U.S. efforts include the International Science and

Technology Center's Project 40, the Cooperative Threat Reduction

program sponsored Russian storage facility and Project Sapphire.

Project 40 will develop an upgraded approach for safeguarding complex

sensitive nuclear fuel cycle facilities. The storage facility will

incorporate MPC&A elements into its design. Under Project Sapphire,

the United States transferred approximately 600 kilograms of weapons

grade HEU from Kazakstan to the United States.

\4 The CTR program was established by Congress in 1991 to help the

newly independent states safely secure, transport, store, and destroy

weapons and weapons material and prevent weapons proliferation. The

program is conducted with the four states that inherited nuclear

weapons when the Soviet Union dissolved: Belarus, Kazakstan, Russia,

and Ukraine. See Weapons of Mass Destruction: Helping the Former

Soviet Union Reduce the Threat: An Update (GAO/NSIAD-95-165, June 9,

1995).

OBJECTIVES, SCOPE, AND

METHODOLOGY

---------------------------------------------------------- Chapter 1:4

Our objectives were to (1) review the nature and extent of problems

with controlling nuclear materials in the NIS; (2) determine the

status and future prospects of U.S. efforts to help strengthen

controls over direct-use nuclear material in Russia, Ukraine,

Kazakstan, and Belarus; and (3) assess plans for consolidating these

efforts in DOE. While seven NIS inherited direct-use nuclear

material, we focused on the four countries that have been the primary

recipients of U.S. assistance--Russia, Ukraine, Kazakstan, and

Belarus.

The scope of our review included direct-use nuclear material

controlled by civilian authorities in the NIS and direct-use material

used for naval nuclear propulsion purposes. We did not review the

protection, control, and accounting systems used for nuclear weapons

in the possession of the Ministry of Defense in Russia. U.S.

officials believe there to be relatively better controls over weapons

in the custody of the Ministry of Defense than over material outside

of weapons.\5 We also did not include in our review the upgrades at

four sites funded by DOE that were not part of the lab-to-lab

program. We recently issued a report that addressed the safety of

facilities in the NIS.\6

To meet our objectives, we reviewed U.S. assessments of the nature

and extent of nuclear material control problems in the NIS; pertinent

program documents, including agreements between DOD and the Russian

Ministry of Atomic Energy (MINATOM), the Ukrainian State Committee on

Nuclear and Radiation Safety, the Ministry of Defense of Kazakstan,

the Ministry of Defense of Belarus, and between DOE and Gosatomnadzor

(GAN); program plans; trip reports; quarterly progress reviews and

State Department cables; and program budget, obligation, and

expenditure data for the CTR-sponsored government-to-government

program and for DOE's lab-to-lab program. We also discussed with DOE

plans to consolidate U.S. MPC&A assistance in DOE.

We interviewed officials from DOD, DOE, the Department of State, the

Nuclear Regulatory Commission, the National Laboratories (including

Los Alamos, Sandia, and Lawrence Livermore), the Pacific Northwest

Laboratory, the National Security Council, and the National Academy

of Sciences. We also interviewed nonproliferation specialists from

the Monterey Institute of International Studies. In Russia, we

interviewed officials from MINATOM, Gosatomnadzor (the Russian

nuclear regulatory agency), the Kurchatov Institute, the Institute of

Physics and Power Engineering, the Elektrostal Machine Building

Plant, the MINATOM nuclear weapons laboratories Arzamas-16 and

Chelyabinsk-70, and the Kazakstan Atomic Energy Agency.

In addition, we toured facilities at the Kurchatov Institute and the

Institute of Physics and Power Engineering, located in the Russian

Federation, to obtain information on current MPC&A systems

implemented at these facilities. We visited sites in Russia that

have been the recipients of U.S. assistance efforts, including the

Elektrostal Machine Building Plant, the Kurchatov Institute, and the

Institute of Physics and Power Engineering. We also witnessed the

demonstration of a model MPC&A system at Arzamas-16.

Our review was conducted between November 1994 and January 1996 in

accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.

--------------------

\5 As part of the CTR program, DOD has an ongoing program with the

Russian Ministry of Defense to enhance the security of nuclear

weapons in Ministry of Defense custody during transportation and

storage.

\6 See Nuclear Safety: Concerns With Nuclear Facilities and Other

Sources of Radiation in the Former Soviet Union (GAO/RCED-96-4 Nov.

7, 1995).

NATURE AND EXTENT OF NUCLEAR

MATERIAL CONTROL PROBLEMS IN THE

NIS

============================================================ Chapter 2

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Russia and six other NIS

inherited hundreds of tons of direct-use nuclear material. Much of

this material is thought to be located at 80 to 100 civilian, naval

nuclear, and nuclear weapons-related facilities, mostly in Russia.

However, U.S. and NIS officials do not know the exact amounts and

locations of this material. Much of it is highly attractive to theft

because it is relatively safe to handle and is not in weapons. U.S.

officials are concerned that social and economic changes in the NIS

have increased the threat of theft and diversion of nuclear material,

and with the breakdown of Soviet-era MPC&A systems, the NIS may not

be as able to counter the increased threat. While as yet there is no

direct evidence that a nuclear black market for stolen or diverted

nuclear material exists in the NIS, the seizures of gram and kilogram

quantities of direct-use material have increased these concerns.

NATURE AND EXTENT OF THE

PROBLEM

---------------------------------------------------------- Chapter 2:1

The Soviet Union produced up to 1,200 metric tons of HEU and 200

metric tons of plutonium. Much of this material is outside of

nuclear weapons, and the stockpile of material outside of weapons is

expected to grow rapidly as Russia proceeds to dismantle its weapons.

The material is considered to be highly attractive to theft because

it is (1) not very radioactive and therefore relatively safe to

handle and (2) in forms that make it readily accessible to theft, for

example, in containers that can easily be carried by one or two

persons or as components from dismantled weapons. This material can

be directly used to make a nuclear weapon without further enrichment

or reprocessing.

Most of the material is located in Russia. Los Alamos National

Laboratory has identified five sectors in the Russian nuclear complex

that handle direct-use material.

Nuclear materials in weapons. (This material is largely in the

custody of the Ministry of Defense.\1 )

The MINATOM defense complex, which contains large amounts of

nuclear material removed from dismantled nuclear weapons and

stockpiles of HEU and plutonium produced for the nuclear weapons

program.

The MINATOM civilian sector, which includes a number of reactor

development institutes such as the Institute of Physics and

Power Engineering at Obninsk, as well as organizations, such as

the Elektrostal Machine Building Factory, that produce nuclear

fuels and materials for civilian applications. (Some of these

institutes and enterprises do both civilian and defense work.)

Civilian research institutes outside of MINATOM, which include the

Kurchatov Institute and facilities run by the Academy of

Sciences, the Ministry of Science, and the Commission on Defense

Industry. (Most of these institutes possess only small

quantities of materials, although some, such as the Kurchatov

Institute, possesses several tons of direct-use material.)

The naval propulsion sector, which includes the Navy and the

Ministry of Shipbuilding. (This sector comprises stockpiles of

HEU used in submarines and icebreakers.)

Other NIS with facilities that handle direct-use material include

Belarus, Georgia, Kazakstan, Latvia, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan.

Generally, the nuclear facilities in these countries are operated by

their respective atomic energy ministries or academies of science and

involve nuclear research centers, research reactors, and, in the case

of Kazakstan, a plutonium breeder reactor.

--------------------

\1 A U.S.-Russian government-to-government agreement concerning

technical exchanges on warhead safety and security was signed in

December 1994. Also, in 1995 a CTR-sponsored DOD and Ministry of

Defense Nuclear Weapons Security Group was formed to coordinate

assistance and cooperation to enhance the security of nuclear weapons

in the custody of the Ministry of Defense during transportation and

storage and to facilitate discussion and information sharing on this

and related issues under the Cooperative Nuclear Weapons Security

Program. Nuclear material in the custody of the Ministry of Defense

was outside the scope of our review.

SOVIET-ERA NUCLEAR MATERIAL

CONTROLS

---------------------------------------------------------- Chapter 2:2

The Soviet Union controlled nuclear materials since the beginning of

its nuclear program in the 1940s. The Soviet approach to controlling

nuclear materials placed a heavy emphasis on internal security, which

corresponded to the political and economic conditions within the

Soviet Union. It placed less emphasis on accounting procedures,

which were used to monitor production, rather than to detect

diversion or ensure the absence of diversion.

The Soviet Union located its nuclear weapons complex in closed secret

cities. The cities were separated from other urban areas,

self-contained, and protected by fences and guard forces. Personnel

working in the Soviet nuclear complex were under heavy surveillance

by the KGB. Personnel went through an intensive screening process,

and their activities were closely monitored. In general, facilities

would control access to nuclear material using a three-person rule,

requiring two facility staff members and at least one person from the

security services to be present when material was handled. The

Soviet-era control system enforced severe penalties for violations of

control procedures.

According to U.S. national laboratory officials, the Soviet system

accounted for nuclear material, although it was not complete, timely,

or accurate. Facilities paid close attention to end-products to meet

production quotas and paid less attention to the use of completely

measured material balances to track net gains and losses of materials

as they were processed or handled. The Soviet system relied on

manual, paper-based systems that made tracking material

time-consuming. They also used standard estimates of rates of loss

for materials that could be held up in processing equipment, such as

pipes, rather then measuring actual losses. According to DOE, in

these respects, the Soviet system of accounting was similar to that

used in the early days of the U.S. nuclear program.

According to Russian officials, traditional Soviet approaches to

nuclear material controls were generally effective because (1) the

Soviet Union was a closed society (separated by a robust iron

curtain) with strict controls over foreign travel by its citizens,

(2) internal security within the Soviet Union was quite rigid and

strict discipline was carried out when controls were violated, and

(3) there was no black market in nuclear materials within the

country.

SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC CHANGES

MAY INCREASE THE THREAT OF

THEFT AND DIVERSION OF

NUCLEAR MATERIAL

-------------------------------------------------------- Chapter 2:2.1

Social and economic changes in the NIS have increased the threat of

theft and diversion of nuclear material, and Soviet-era MPC&A systems

may not be able to adequately counter the increased threat. The

major nuclear facilities in the MINATOM weapons complex are no longer

secret, and access to these facilities, along with the other nuclear

facilities in the NIS, has increased. According to a U.S.

government assessment, (1) the difficult economic situation has led

to a loss of prestige for nuclear workers, (2) inflation and late

payment of wages have eroded the value of salaries, and (3) pervasive

corruption in society and the increasing potency of a strong criminal

element have weakened the insider protection program based on

personnel surveillance.

With these changes, Russian and U.S. officials have become

increasingly concerned about growing insider and outsider threats of

nuclear theft. According to an official from one of MINATOM's major

facilities in its nuclear weapons complex, the insider threat at the

facility has increased due to the frustrations of the institute's

workers who had not been paid in months. According to this official,

this causes changes in their attitudes toward their work and places

pressures on their families. The outsider threat has also increased

at this facility because the closed city is now open to

businesspeople and outside workers who visit for short periods of

time. According to this official, the institutes do not have

background information on the visitors. Consequently, they have a

lower level of trust in the visitors than in the employees who have

been working at the facility. According to this official, while no

nuclear material has been stolen from this facility, other precious

metals such as platinum and gold have been.

CURRENT STATUS OF NUCLEAR

MATERIAL CONTROLS AT NIS

FACILITIES

---------------------------------------------------------- Chapter 2:3

With the erosion of traditional nuclear controls, current nuclear

control systems in the NIS have weaknesses that could result in the

theft of direct-use materials. The NIS may not have complete and

accurate inventories of their nuclear materials, and some material

may have been withheld from facility accounting systems. Nuclear

facilities rely on antiquated accounting systems and practices that

cannot quickly detect and localize nuclear material losses. Many NIS

facilities also lack certain types of modern equipment that can

detect unauthorized attempts to remove nuclear material from

facilities.

THE NIS MAY NOT HAVE

ACCURATE AND COMPLETE

INVENTORIES

-------------------------------------------------------- Chapter 2:3.1

The NIS may not have accurate and complete inventories of the

direct-use material they inherited from the former Soviet Union.

According to a GAN official, the nuclear safeguard system inherited

from the former Soviet Union was not a comprehensive system. The

Soviet Union did not have a national material control and accounting

system and according to a Russian laboratory official, the Soviet

Union did not conduct comprehensive physical inventories of nuclear

material at its nuclear facilities. Some of the facilities we

visited, such as the Kurchatov Institute, were in the process of

conducting such a comprehensive inventory, but it was not completed

at the time of our visit. At the Institute of Physics and Power

Engineering, officials were conducting an inventory of 70,000 to

80,000 small disk-shaped fuel elements containing direct-use uranium

and plutonium at one reactor. When we visited the facility, they did

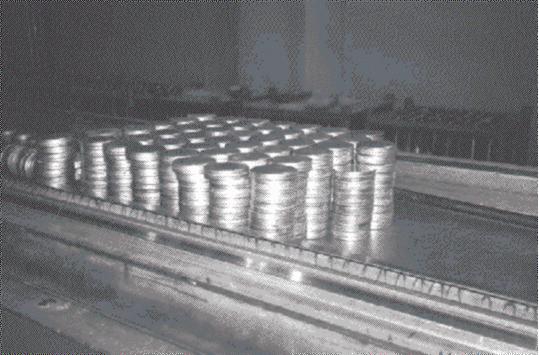

not have an exact count of the elements. Figure 2.1 shows examples

of the small disk-shaped fuel elements we observed at this facility

that could be attractive to theft.

Figure 2.1: Examples of Small,

Disk-Shaped Fuel Elements to Be

Inventoried

U.S. and Russian officials are also concerned that some direct-use

nuclear material has not yet been discovered at NIS nuclear

facilities. According to U.S. national laboratory officials, some

nuclear material may have been withheld from facility accounting

systems so that plant managers could make up shortfalls in meeting

their production quotas. According to another national laboratory

official, organizations do not always share information with one

another on the location and availability of specific nuclear

products. Russian officials are concerned that they have no real

information on the amounts or presence of some nuclear material and

that this material has yet to be discovered. According to a DOD

official, HEU for a Soviet navy reactor program that was terminated

years earlier was discovered by Kazakstani officials after the Soviet

Union dissolved. This HEU, enough for over two dozen nuclear

weapons, was transferred from Kazakstan to the United States under

Project Sapphire.

U.S. officials are uncertain as to whether they have identified all

facilities within the NIS where direct-use material is located. The

United States has identified 80 to 100 facilities that handle

direct-use material in the NIS. However, according to a DOE

official, there may be as many as

35 additional facilities where such material is handled.

MATERIAL ACCOUNTING AND

CONTROL SYSTEMS WOULD HAVE

DIFFICULTY QUICKLY DETECTING

DIVERSION OR THEFT

-------------------------------------------------------- Chapter 2:3.2

Many nuclear facilities in the NIS rely on manual, paper-based

material accounting systems that cannot quickly locate and assess

material losses, rather than computer-based systems. Nuclear

facility operators have to manually check hundreds of paper records

to determine if material is missing. In contrast, U.S. nuclear

facilities use computers extensively to maintain current information

on the presence and quantity of all material. U.S. facilities are

capable of updating nuclear material accounting information within 24

hours, and some can update material accounting information within 4

hours.

Russian accounting systems do not provide systematic coverage of

materials through all phases of the nuclear fuel cycle.\2 According

to U.S. national laboratory officials, these systems do not

adequately measure or inventory material held up in processing

equipment and pipes or material disposed of as waste.

In addition, NIS facilities do not make full use of measured nuclear

material balances, which makes it difficult to detect thefts

occurring over a long period of time. According to a Los Alamos

National Laboratory official, these facilities typically weigh

material at certain points in production and generally measure

radiation emitted from the material. These procedures, while useful

in identifying the types of material present, are less rigorous than

required in the United States because they do not measure the

quantity of material. Diversions of small amounts of nuclear

material could go undetected over time without more accurate

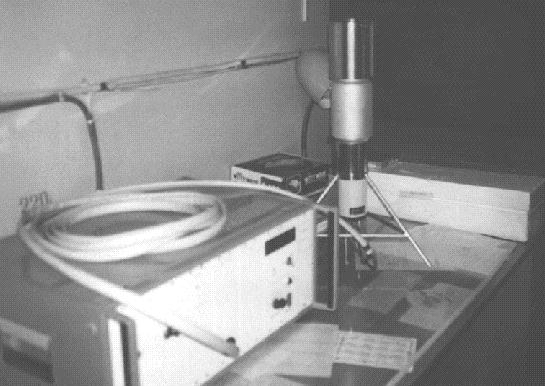

measurements. Figure 2.2 shows a Russian radiation measuring

instrument we observed being used at a facility to identify the types

of material present in reactor fuel elements.

Figure 2.2: A Russian

Radiation Measuring Instrument

Used to Identify the Uranium

and Plutonium Content of Fuel

Elements

Nuclear facilities in the NIS also use material control equipment

that could be made more resistant to tampering by insiders. For

example, nuclear material containers and vaults are sealed with a

wire and wax seal system that could be removed and replaced without

detection. In contrast, in the United States, material is sealed

using numbered copper seals that are controlled and crimped, making

them much more resistant to tampering.

--------------------

\2 The nuclear fuel cycle refers to a sequence of operations

involving supplying nuclear fuel for reactors, irradiating fuel in

reactors, and handling or storing nuclear fuel.

MATERIAL PROTECTION SYSTEMS

LACK MODERN EQUIPMENT

-------------------------------------------------------- Chapter 2:3.3

Material protection systems at NIS nuclear facilities have weaknesses

that could result in the inability to detect insiders or outsiders

trying to steal nuclear material. In the United States, sites

handling direct-use material are protected by two fences; various

sensors designed to delay and detect intruders as they approach a

facility; and television cameras, which allow facility personnel to

assess the nature of the threat. The nuclear facilities we visited

in Russia for the most part did not have such equipment. For

example, during our visit to the Kurchatov Institute, we noticed that

a concrete fence protecting the main facility was crumbling. The

fence appeared to lack television monitors or other sensors. A fence

used to protect another site at the institute with large quantities

of direct-use material did not appear to have any sensors or

television cameras to detect intrusion and had vegetation that could

obscure intruders or those leaving the facility.

We toured another site at the Kurchatov Institute where several

hundred kilograms of direct-use material were present. Although the

site was within the walled portion of the institute, there was no

fencing or other intrusion delay and assessment system around the

site. Although we were accompanied by an institute official who had

cleared our visit with security personnel, we were able to gain

access without showing identification. One unarmed security guard

was posted within the building. In contrast, during a visit to a

Sandia National Laboratory facility in New Mexico, we were required

to show identification and display security badges while we visited a

facility with large amounts of direct-use material. This facility

had numerous armed guards inside and outside the site.

REPORTS OF DIVERSION OF

DIRECT-USE MATERIAL

---------------------------------------------------------- Chapter 2:4

According to U.S. officials, there is no direct evidence that a

nuclear black market linking buyers, sellers, and end-users exists

for stolen or diverted nuclear material in the NIS. However, the

seizure of gram and kilogram quantities of direct-use material in

Russia, Germany, and the Czech Republic have increased concerns about

the effectiveness of MPC&A systems in the NIS.

The first case involving the theft or diversion of direct-use

material appeared in Russia in 1992. According to U.S. officials,

the more significant cases included the following:

From May to September 1992, 1.5 kilograms of weapons grade HEU were

diverted from the Luch Scientific Production Association in

Russia by a Luch employee. According to a nonproliferation

analyst, the material was diverted in small quantities about 20

to 25 times during the period. The employee was apprehended en

route to Moscow.

In March 1994, three men were arrested in St. Petersburg trying to

sell

3.05 kilograms of weapons-usable HEU. According to U.S.

officials, Russian media articles claim that the material was

smuggled out of a MINATOM facility located near Moscow in an

oversized glove.

On May 10, 1994, 5.6 grams of nearly pure plutonium-239 were seized

by German officials.

On August 10, 1994, 560 grams of a mixed-oxide uranium plutonium

mixture were seized at Munich Airport from a flight originating

from Moscow.

On December 14, 1994, 2.72 kilograms of weapons-grade uranium were

seized by police in Prague.

U.S. officials stated that they have not uncovered any direct links

between buyers of direct-use materials and end-users that would use

the material for weapons purposes. However, the cases are troubling

for several reasons.

The cases are the first to involve gram and kilogram quantities of

direct-use material.

They show that individuals are willing to take high risks to

traffic in smuggled direct-use material.

While scientific analysis cannot pinpoint which facilities the

material seized in Europe originated from, the criminal

investigations suggest that the material may have come from the

NIS.

The detection of nuclear smuggling so far has been by chance,

rather than by reliance on physical protection control and

accounting systems, or customs checks at the borders of the NIS.

CURRENT STATUS AND FUTURE

PROSPECTS FOR U.S. ASSISTANCE TO

THE NIS

============================================================ Chapter 3

The United States is pursuing two different, but complementary

strategies to achieve its goals of rapidly improving nuclear material

controls over direct-use material in the NIS. The CTR-sponsored

government-to- government program, which works directly with the NIS,

is only now beginning to improve controls over direct-use material

because (1) until January 1995, Russia's MINATOM was reluctant to

cooperate with the U.S. program because of security concerns and (2)

work at non-Russian facilities with direct-use material is in the

early stages of implementation. The DOE lab-to-lab program, which

works directly with Russian nuclear facilities, has improved controls

over direct-use material at five facilities during its first full

year of implementation.\1

Despite the slow start, the prospects for U.S. efforts to enhance

MPC&A in the NIS are improving. Russia and the United States agreed

in June 1995 to add five high-priority sites that have large amounts

of direct-use material to the CTR-sponsored government-to-government

program. In Kazakstan and Ukraine, the CTR-sponsored MPC&A program

is progressing steadily with improvements at several sites with

direct-use nuclear material. DOE also signed an agreement with GAN,

the Russian nuclear regulatory agency, in June 1995 to cooperate on

the establishment of a national nuclear materials control and

accounting system in Russia. DOE's lab-to-lab program is also

expanding to cover MINATOM nuclear weapons facilities.

--------------------

\1 The five facilities where controls over direct-use material have

been improved are the Kurchatov Institute, the Institute of Physics

and Power Engineering, Chelyabinsk-70, Arzamas -16, and Tomsk-7. All

are located in Russia.

U.S. MPC&A ASSISTANCE PROGRAMS

IN THE NIS

---------------------------------------------------------- Chapter 3:1

Both DOD's CTR-sponsored government-to-government program and DOE's

lab-to-lab program were designed to demonstrate MPC&A technology at

model facilities and facilitate the transfer of MPC&A improvements to

other nuclear facilities in the NIS. The CTR-sponsored program works

with the governments of Russia, Ukraine, Kazakstan, and Belarus to

upgrade civilian MPC&A at selected facilities and develop

regulations, enforcement procedures, and national material tracking

systems. DOE's lab-to-lab program works directly with Russian

nuclear facilities to upgrade their MPC&A controls.

The two programs differ in their strategies to improve MPC&A in the

NIS. The CTR- sponsored program is implemented by DOE through direct

government-to-government agreements between DOD and the respective

Ministries responsible for atomic energy in Russia, Ukraine,

Kazakstan, and Belarus. The agreements and their amendments specify

the total amount of funds available to the programs in each country,

identify the types of facilities that will participate, establish the

roles and responsibilities of the participating organizations, and

establish rights to audit and examination by U.S. officials. To the

maximum extent feasible, the CTR-sponsored MPC&A programs use U.S.

goods and services.

DOE's lab-to-lab program, in contrast, is implemented directly with

Russian nuclear facilities. DOE's national laboratories

participating in the program sign contracts directly with their

Russian laboratory counterparts, and DOE's national laboratories can

purchase goods and services from U.S., Russian, or other suppliers as

needed. The program includes complete MPC&A upgrades at specific

facilities, or the rapid deployment of a particular MPC&A element,

such as portal monitors, as needed.

CTR GOVERNMENT-TO-GOVERNMENT

PROGRAM STATUS

-------------------------------------------------------- Chapter 3:1.1

The CTR-sponsored government-to-government program is funding

projects in Russia, Ukraine, Kazakstan, and Belarus for improving

civilian nuclear material controls at selected model facilities and

developing regulations, enforcement procedures, and national material

tracking systems. Figure 3.1 shows the location of current

CTR-sponsored government-to- government projects.

Figure 3.1: Current CTR

Government-to-Government

Projects in Russia, Ukraine,

Kazakstan, and Belarus

In Russia, CTR funds have supported MPC&A upgrades for a low-enriched

uranium fuel fabrication facility and a training center. In Ukraine

and Kazakstan, the program has funded site surveys at facilities that

use direct-use material and lower priority material and assisted

national authorities in establishing MPC&A regulations and reporting

systems. In Belarus, the program has funded a site survey at a

facility using direct-use material and is assisting the Belarussian

government in establishing MPC&A regulations and a reporting system.

Since the beginning of the CTR-sponsored program in 1991, DOD has

budgeted $63.5 million for government-to-government MPC&A assistance,

obligated $59.2 million, and spent $3.8 million. The government-to-

government program has provided working group meetings, site surveys,

physical protection equipment, computers, and training for projects

in Russia, Ukraine, Kazakstan, and Belarus. As of January 1996, none

of the projects have been completed. Table 3.1 shows the

distribution of CTR government-to-government program funds among

Russia, Ukraine, Kazakstan, and Belarus.

Table 3.1

U.S. Assistance for CTR-Sponsored

Government-to-Government Programs

(fiscal years 1991-95)

(Dollars in millions)

Country Budget Obligations Expenditures\a

-------------------------- ------------ ------------ --------------

Russia\b $30.0 $27.5 $2.0

Ukraine 22.5 21.5 0.7

Kazakstan 8.0 7.6 1.1

Belarus 3.0 2.6 0

======================================================================

Total $63.5 $59.2 $3.8

----------------------------------------------------------------------

\a Our prior work found that DOD's expenditure data can significantly

understate the value of work performed to date. Although we were

unable to obtain data on the value of work performed for the

government-to-government program, our prior report found that the

value of work performed for CTR projects was almost double the

expenditures reported by the program. See Weapons of Mass

Destruction: Reducing the Threat From the Former Soviet Union: An

Update (GAO/NSIAD-95-165, June 9, 1995) p.10.

\b The $30 million budgeted and $27.5 million obligated for Russia

does not include $15 million in fiscal year 1995 CTR funds for MPC&A

upgrades implemented under DOE's lab-to-lab program.

By July 1995, the CTR-sponsored government-to-government program had

started to improve physical protection at a facility with direct-use

material. The slow pace of the government-to-government program in

Russia can be attributed to two major obstacles. The first obstacle

involved difficulties in negotiating agreements with MINATOM to

obtain access to sites handling direct-use material. The United

States proposed to MINATOM in March 1994 that demonstration projects

be initiated at two HEU fuel fabrication facilities. The U.S.

position was that including these facilities would support

nonproliferation objectives. MINATOM rejected the U.S. proposal

saying that the inclusion of direct-use material was a sensitive and

delicate issue and that experience in cooperating on low enriched

uranium facilities would be needed before expanding to direct-use

materials. As a result, the United States agreed to fund only one

project in Russia, the low enriched uranium facility at Elektrostal.

Recently, physical protection equipment was installed in the building

housing the low enriched uranium fuel line. The same building also

houses an HEU fuel fabrication line, which will be protected by this

equipment. In the summer of 1994, the United States proposed a

quick-fix approach to upgrade MPC&A at Russian facilities with

direct-use material. Under this approach, the United States would

provide expedited assistance to upgrade nuclear material security at

key Russian nuclear facilities. Russian officials were not

supportive of the approach citing concerns about providing the United

States access to sensitive nuclear facilities.

The second obstacle was MINATOM's resistance in recognizing the role

of GAN as a nuclear regulatory entity and GAN's own lack of statutory

authority for oversight and enforcement of nuclear regulations.

According to State Department officials, GAN was often at odds with

MINATOM about the ongoing transition of regulatory authority to GAN.

Also, GAN was unable to assert its regulatory role because it lacked

legislative authority to regulate facilities with nuclear materials.

In addition, despite a decree issued in September 1994 by the Russian

President, that named GAN as the lead agency in overseeing the

security of nuclear materials in Russia and ordered MINATOM to work

with GAN on this issue, there are still disputes over authority

between ministries that have not been resolved.

In Ukraine, Kazakstan, and Belarus, the CTR-sponsored government-to-

government program is working to improve MPC&A systems at nuclear

facilities, develop national MPC&A systems, and help them prepare for

International Atomic Energy Agency safeguards pursuant to the Nuclear

Nonproliferation Treaty. However, CTR-sponsored projects are just

beginning, and improvements to controls at the first facility

handling direct-use materials will not be completed until mid-1996 at

the earliest.

In Ukraine, the program has completed a site survey for the Kiev

Institute of Nuclear Research, which uses direct-use material for

fuel in a research reactor and has started delivering access control

equipment. The program is also in the process of conducting a site

survey at the Kharkiv Institute of Physics and Technology, which also

contains direct-use material. The program is also implementing an

MPC&A project at the South Ukraine Power Plant, which is a lower

priority site because it uses low enriched uranium for fuel. Work at

the Kiev Institute is expected to be completed by mid-1996, and work

at the other sites is expected to be completed by the end of fiscal

year 1997. The program has also established a computer network for

the State Committee for Nuclear and Radiation Safety to facilitate

the creation of Ukraine's national nuclear database.

In Kazakstan, the focus of CTR-funded work has been on the Ulba Fuel

Fabrication Plant, a low-priority site that produces low enriched

uranium fuel elements for power reactors. The program also conducted

site surveys for research reactor sites at Semipalatinsk and Almaty

and for a breeder reactor at Aktau. DOE expects the program in

Kazakstan to be completed by the end of 1997.

In Belarus, the program is upgrading MPC&A systems for direct-use

material at the Sosny Research Center in cooperation with Sweden and

Japan, helping Belarus develop national regulations, and preparing

the government for International Atomic Energy Agency safeguards.

The program has completed a site survey and delivered access control

equipment and interior sensors to Sosny. DOE expects the program in

Belarus to be completed by the end of 1996.

LAB-TO-LAB PROGRAM STATUS

-------------------------------------------------------- Chapter 3:1.2

The lab-to-lab program is funding projects in Russia to improve MPC&A

at sites within nuclear facilities, demonstrate MPC&A technologies,

and deploy MPC&A equipment on an as-needed basis. Figure 3.2 shows

the location of current lab-to-lab projects.

Figure 3.2: Current Lab-to-Lab

Projects

The lab-to-lab program has completed pilot projects at the Kurchatov

Institute in Moscow and the Institute of Physics and Power

Engineering and has demonstrated a model material control and

accounting system at Arzamas-16, a MINATOM nuclear weapons facility.

In addition, the program has deployed nuclear portal monitors around

a nuclear site at Chelyabinsk-70, a second MINATOM nuclear weapons

facility, the Kurchatov Institute, the Institute of Automatics, the

Institute of Physics and Power Engineering, and Arzamas-16. Table

3.2 shows obligations and expenditures for the lab-to-lab program.

Table 3.2

U.S. Assistance for Lab-to-Lab Programs

(fiscal years 1994-95)

(Dollars in millions)

Fiscal year Budget Obligations Expenditures

---------------------------- ------------ ------------ ------------

1994 $2.1 $2.1 $1.6

1995 15.0 15.0 12.7\a

======================================================================

Total $17.1 $17.1 $14.3

----------------------------------------------------------------------

\a According to a national laboratory official, in fiscal year 1995,

DOE advanced and spent $8.2 million of its own funds for the

lab-to-lab program, while waiting for a transfer of $15 million from

the CTR program. Of the $15 million transferred from DOD to DOE, DOE

spent $4.5 million on the lab-to-lab program in fiscal year 1995 and

carried over $10.5 million into fiscal year 1996.

The pilot project at the Kurchatov Institute improved MPC&A for a

reactor site containing about 80 kilograms of direct-use material.

The improvements included a new fence, sensors, a television

surveillance system to detect intruders, a nuclear material portal

monitor, a metal detector at the facility entrance, improved

lighting, alarm communication and display systems, an intrusion

detection and access control system in areas where nuclear material

is stored, and a computerized material accounting system.

Figure 3.3 shows the types of improvements we observed during our

visit to the Kurchatov Institute reactor site in March 1995.

Figure 3.3: Lab-to-Lab

Cooperative Efforts at the

Kurchatov Institute in Moscow

At Obninsk, the program has upgraded MPC&A systems for a research

reactor facility that houses several thousand kilograms of direct-use

material.\2 The program is providing a computerized material control

and accounting system; entry control; portal monitoring systems; a

vehicle monitor; and bar codes to be attached to the discs, seals,

and video surveillance systems. In addition, the program will assist

the facility with taking a physical inventory and performing

radiation measurements to quantify the amount of material present.

The first phase of this project was completed in September 1995.

A pilot demonstration project was also completed with Arzamas-16 in

March 1995. This project demonstrated MPC&A technologies that could

be applied to MINATOM nuclear weapons facilities and the

CTR-sponsored fissile material storage facility. Using U.S.- and

Russian-supplied equipment, the demonstration consisted of

computerized accounting systems; a system to measure nuclear

materials in containers; access control systems; a monitored storage

facility using cameras, seals, and motion detector equipment; and a

system to search for and identify lost or stolen material. Although

this project did not have a direct or immediate impact on protecting

direct-use material, it has led to greater interest in participation

in the lab-to-lab program by MINATOM defense facilities. Figure 3.4

shows U.S.- and Russian-supplied equipment that we observed in use

during the March 1995 Arzamas-16 demonstration project.

Figure 3.4: Lab-to-Lab

Cooperative Efforts at

Arzamas-16

The lab-to-lab program is also rapidly deploying nuclear material

portal monitors to Russian institutes, enterprises, and operating

facilities. Starting in June 1995, the lab-to-lab program assisted

Chelyabinsk-70 in deploying two nuclear material portal monitors and

a vehicular portal monitor at the entrances to a key nuclear site.

This effort was in response to increased concerns of Chelyabinsk

officials about controlling access to the site. Nuclear material

portal monitors have also been installed at an engineering test

facility at Arzamas-16 and at one of the main entrances to the

Institute of Automatics, where the monitors are undergoing testing

and evaluation. The lab-to-lab program has also started delivering

portal monitors to Tomsk-7. The program officials have signed a

contract to install monitors at all portals at Tomsk-7.

--------------------

\2 This material is especially attractive to theft because it is in

the form of 70,000 to 80,000 small disks containing HEU and

plutonium, along with other material.

PROSPECTS FOR MPC&A UPGRADES

ARE IMPROVING

---------------------------------------------------------- Chapter 3:2

While the CTR-sponsored government-to-government program has gotten

off to a slow start controlling direct-use material, the U.S.

government is making progress in expanding participation in the

program to more facilities with direct-use material in the NIS. The

lab-to-lab program is also expanding its outreach to additional

facilities in Russia that require MPC&A upgrades, and DOE officials

have been approached by the Russians to expand their efforts to other

facilities.

CTR GOVERNMENT-TO-GOVERNMENT

PROGRAM EXPANDS ITS PROJECTS

TO DIRECT-USE SITES IN

RUSSIA

-------------------------------------------------------- Chapter 3:2.1

In January 1995, the United States and Russia agreed to expand the

CTR-sponsored government-to-government program to facilities using

direct-use material. An agreement was signed in June 1995 at the

Gore-Chernomyrdin Commission meeting to add five direct-use

facilities.\3 These are high-priority facilities because they handle

large amounts of direct-use material. They include the HEU fuel