HOME | CHAPTER 10 CONTENTS | CHAPTER 10 SUMMARY

CHAPTER 10 TEXT | CHAPTER 10 NOTES

Chapter 10 Contents

CHAPTER SUMMARY

MANUFACTURING PROCESSES: PRC EFFORTS TO ACQUIRE MACHINE TOOL AND JET ENGINE TECHNOLOGIES

PRC TARGETING OF ADVANCED MACHINE TOOLS

Export Controls on Machine Tools

Export Administration Regulations

The PRC's Machine Tool Capabilities and Foreign Acquisitions

CASE STUDY: McDONNELL DOUGLAS MACHINE TOOLS

Findings of the U.S. General Accounting Office

The U.S. Government's Actions in Approving the Export Licenses

Intelligence Community Assessments

Changes to the Trunkliner Program

Commerce Department Delays Investigating Machine Tool Diversion for Six Months

The Commerce Department's Actions in April 1995

The Commerce Department's Actions in October 1995

Allegation that the Commerce Department Discouraged the Los Angeles Field Office's Investigation

PRC Diversion of Machine Tools

CATIC Letter Suggests Trunkliner Program at Risk

CATIC's Efforts to Create the Beijing Machining Centerwith Monitor Aerospace

CHRONOLOGY OF KEY EVENTS

PRC TARGETING OF U.S. JET ENGINES

AND PRODUCTION TECHNOLOGYCASE STUDY: GARRETT ENGINES

PRC Targeting of Garrett Engines

U.S. Government Approval of

the Initial Garrett Engine ExportsCommerce Department Decontrol of the Garrett Jet Engines

The Interagency Review of the Proposed Export

of Garrett Jet EnginesConsideration of Enhanced

Proliferation Control Initiative RegulationsConsideration of COCOM

and Export Administration RegulationsTHE PRC CONTINUES TO ACQUIRE

JET ENGINE PRODUCTION PROCESSESTECHNICAL AFTERWORD: The PRC's Acquisition of Machine Tools, Composite Materials, and Computers for Aircraft and Missile Manufacturing

CHAPTER 10 NOTES

Chapter 10 Summary

achine tool and jet engine technologies are priority acquisition targets for the PRC. This chapter presents two case studies relating to the PRC's priority efforts to obtain such technology - its 1994 purchase of machine tools from McDonnell Douglas, and its efforts in the late 1980s and early 1990s to obtain jet engine technology from Allied Signal's Garrett Engine Division.McDonnell Douglas Machine Tools

In 1993, China National Aero-Technology Import and Export Corporation (CATIC) agreed to purchase a number of excess machine tools and other equipment from McDonnell Douglas, including 19 machine tools that required individual validated licenses to be exported. CATIC told McDonnell Douglas it was purchasing the machine tools to produce parts for the Trunkliner Program, a 1992 agreement between McDonnell Douglas and CATIC to build 40 MD-82 and MD-90 series commercial aircraft in the PRC.

During the interagency licensing process for the machine tools, the Defense Technology Security Administration sought assessments from the Central Intelligence Agency and from the Defense Intelligence Agency, because of concerns that the PRC could use the McDonnell Douglas five-axis machine tools for unauthorized purposes, particularly to develop quieter submarines. Since the PRC wishes to enhance its power projection capabilities and is making efforts to strengthen its naval forces, the five-axis machine tools could easily be diverted for projects that would achieve that goal.

Initially, CATIC told McDonnell Douglas it planned to sell the machine tools to four factories in the PRC that were involved in the Trunkliner commercial aircraft program. When those efforts reportedly failed, CATIC told McDonnell Douglas it planned to use the machine tools at a machining center to be built in Beijing to produce Trunkliner parts for the four factories.

In May 1994, McDonnell Douglas applied to the Commerce Department for licenses to export the 19 machine tools to the PRC. Even after it became apparent that only 20 of the 40 Trunkliner aircraft would be built in the PRC, the U.S. Government continued to accept McDonnell Douglas's assertion that the machine tools were still required to support the Trunkliner production requirements. Accordingly, Commerce approved the license applications in September 1994 with a number of conditions designed to limit the risk of diversion or misuse.

In April 1995, the U.S. Government learned from McDonnell Douglas that six of the licensed machine tools had been diverted to a factory in Nanchang known to manufacture military aircraft and cruise missile components, as well as commercial products. However, Commerce's Office of Export Enforcement (OEE) did not initiate an investigation of the diversion for six months.

The Commerce Department declined an Office of Export Enforcement Los Angeles Field Office request for a Temporary Denial Order against CATIC. The case remains under investigation by OEE and the U.S. Customs Service. With the approval of the U.S. Government, the machine tools have since been consolidated at a factory in Shanghai.

Garrett Engines

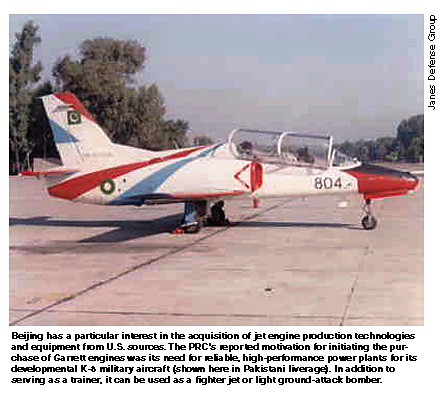

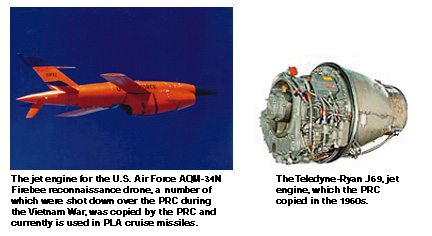

The PRC has obtained U.S. jet engine technology through diversions of engines from commercial end uses, by direct purchase, and through joint ventures. Although the United States has generally sought to restrict the most militarily sensitive jet engine technologies and equipment, the PRC has reportedly acquired such technologies and equipment through surreptitious means.

Prior to 1991, Garrett jet engines had been exported to the PRC under individual validated licenses that included certain conditions to protect U.S. national security. These conditions were intended to impede any attempt by the PRC to advance its capability to develop jet engines for military aircraft and cruise missiles.

The 1991 decision by the Commerce Department to decontrol Garrett jet engines ensured that they could be exported to the PRC without an individual validated license or U.S. Government review. In 1992, the Defense Department learned of negotiations between Allied Signal's Garrett Engine Division and PRC officials for a co-production deal that prompted an interagency review of Commerce's earlier decision. The interagency review raised a number of questions regarding the methodology Commerce had followed in its decision to decontrol the Garrett jet engines.

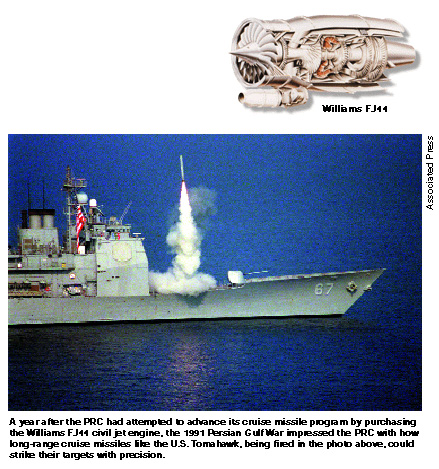

The PRC continues its efforts to acquire U.S. jet engine production technology. The PRC may have also benefited from the direct exploitation of specially designed U.S. cruise missile engines. According to published reports, the PRC examined a U.S. Tomahawk cruise missile that had been fired at a target in Afghanistan in 1998, but crashed en route in Pakistan.

Chapter 10 Text

MANUFACTURING PROCESSES

PRC EFFORTS TO ACQUIRE

MACHINE TOOL AND

JET ENGINE

TECHNOLOGIES

he People's Republic of China's long-term goal is to become a leading power in East Asia and, eventually, one of the world's great powers. To achieve these aims, the PRC will probably enhance its military capabilities to ensure that it will prevail in regional wars and deter any global strategic threat to its security.1From the PRC's perspective, the 1991 Gulf War was a watershed event in which U.S. weapons and tactics proved decisive. The war provided a window on future warfare as well as a benchmark for the PRC's armed forces.2

After the Gulf War, senior PRC military leaders began speaking of the need to fight future, limited wars "under high-tech conditions." 3 Senior PRC political leaders support the military's new agenda.4

In a 1996 speech, Li Peng, second-ranking member of the Politburo, then-Prime Minister, and currently Chairman of the National People's Congress, said:

We should attach great importance to strengthening the army through technology, enhance research in defense-related science, . . . give priority to developing arms needed for defense under high-tech conditions, and lay stress on developing new types of weapons.5

Senior PRC leaders recognize that enormous efforts must be made to "catch up" militarily with the West.6 According to the Defense Intelligence Agency, the PRC's ability to achieve this goal depends in part on its "industrial capacity to produce advanced weapons without foreign technical assistance." 7

Two technologies that have been identified as priority acquisition targets for the PRC are machine tools for civil and military requirements, and jet engine technology.8 This chapter presents two case studies relating to the PRC's efforts to obtain such technologies - its 1994 purchase of machine tools from McDonnell Douglas, and its efforts in the late 1980s and early 1990s to obtain jet engine technology from Allied Signal's Garrett Engine Division.

These case studies illustrate the methods the PRC has used to acquire militarily-sensitive technologies through its skillful interaction with U.S. Government and commercial entities.

However, the case studies do not assess the degree to which the PRC has enhanced its aerospace and military industrial capabilities through the acquisition of U.S. technologies and equipment.

A third technology priority for the PRC - composite materials - is discussed in the Technical Afterword to this chapter.

PRC Targeting of Advanced Machine Tools

The PRC is committed to the acquisition of Western machine tool technology, and the advanced computer controls that provide the foundation for an advanced aerospace industry.

Although the PRC acquires machine tools from foreign sources in connection with commercial ventures, it also seeks foreign-made machine tools on a case-by-case basis to support its military armament programs.

Moreover, the proliferation of joint ventures and other commercial endeavors that involve the transfer or sale of machine tools to the PRC makes it more difficult for foreign governments and private industry to distinguish between civilian and military end-uses of the equipment.

The China National Aero-Technology Import-Export Corporation's (CATIC) purchase of used machine tools from McDonnell Douglas, now part of Boeing, is one illustration of the complexities and uncertainties faced by private industry and the U.S. Government in these endeavors.

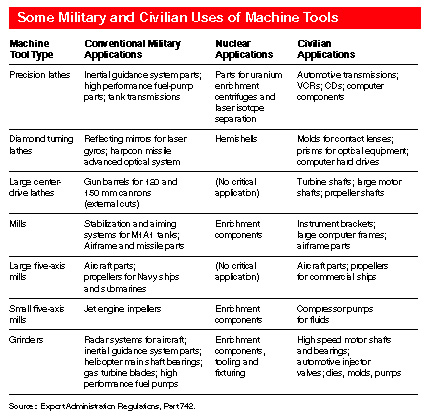

Traditional machine tools cut, bend, and shape metals and non-metal materials to manufacture the components and structures of other machines. Machine tools form the foundation of modern industrial economies, and are widely used in the aerospace and defense industries.

The capability of machine tools is typically indicated by the number of linear or rotational motions - of either the tool or the workpiece - that can be continuously controlled during the machining process, and by the machining accuracy that can be achieved. The latter is measured in microns, that is, millionths of a meter.

Advanced machine tools can provide five axes of motion - typically horizontal, lateral, and vertical movement, and rotation on two perpendicular axes. Less widely used or required are six- and seven-axis machines, which are sometimes used for special applications.

Machine tools used in aircraft and defense manufacturing today are generally numerically controlled (NC). More advanced equipment is computer numerically controlled (CNC). CNC machine tools are essential to batch production of components for modern weapon systems, and can reduce machining times for complex parts by up to 90 percent compared to conventional machine tools.

In addition, these modern machines require operators with less skill and experience and, when combined with computer-aided design software, can reduce the manufacturing cycle of a product, from concept to production, from months to days.

Machine tools are essential to commercial industry, and high precision, multiple-axis machine tools broaden the range of design solutions for weapon components and structural assemblies. Parts and structures can be designed with advantages in weight and cost relative to what could be achieved with less advanced machine tools. For military and aerospace applications, the level of manufacturing technology possessed by a country directly affects the level of military hardware that can be produced, and the cost and reliability of the hardware.9

The military/civilian dual-use production capability of various types of machine tools is indicated in the following table.

Export Controls on Machine Tools

The PRC's access to foreign multi-axis machine tools and controllers has increased rapidly with liberalized international export controls.10

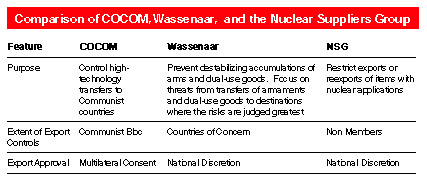

During the Cold War, the Coordinating Committee for Multilateral Export Controls (COCOM) established multilateral controls on exports to the Warsaw Pact allies and the PRC of machine tools that restricted linear positioning accuracy below 10 microns.11 However, the consensus for relatively strict export controls dissolved after the Soviet Union's collapse.

The post-Cold War control regime is embodied in the 1996 Wassenaar Arrangement, and the 1978 Nuclear Suppliers Group Agreement (NSG) governing the export of machine tools that can be used for nuclear weapons development. This current regime has a different focus, as indicated in the following table.

The Wassenaar and Nuclear Suppliers Group Agreement regimes have adopted similar control parameters for machine tools. Generally speaking, lathes and milling machines must be licensed for export if their accuracy exceeds six microns. Grinding machines are controlled at four microns. The Wassenaar Arrangement controls all machine tools capable of simultaneous, five-axis motion, regardless of machining accuracy. The Nuclear Suppliers Group Agreement exempts certain machines from this restriction.12

The PRC is not a proscribed destination for machine tools and other commodities under the Wassenaar Arrangement. This means that Wassenaar regime members treat exports to the PRC according to their individual national discretion. On the other hand, exports to the PRC of Nuclear Suppliers Group Agreement-covered items require individual validated licenses.13

Export Administration Regulations

The Wassenaar and Nuclear Suppliers Group Agreement parameters for machine tool controls have been incorporated in the U.S. Commerce Department's Commodity Control List of dual-use items (the list appears in the Export Administration Regulations).14 Machine tools are listed under Category 2 (Material Processing), Group B (Inspection and Production Equipment).15

The Commodity Control List further classifies machine tools - as it does other dual-use items - by an Export Control Classification Number that reflects the item's category, group, types of associated controls, whether the item is controlled for unilateral or multilateral concerns, and a sequencing number to differentiate among items on the Commodity Control List.16

The PRC's Machine Tool Capabilities and Foreign Acquisitions

Observers of the PRC's machine tool capabilities do not believe that the PRC can indigenously produce high precision, five-axis machines that approach the quality of Western products.

The U.S. General Accounting Office estimates that the PRC has the capability "to manufacture less sophisticated machine tools, but cannot currently mass produce four- and five-axis machine tools that meet Western standards." 17

According to a 1996 Defense Department assessment, however, the PRC's indigenous machine tool production capability is increasing markedly.18

The PRC has long sought to compensate for its deficiencies in machine tool technology by importing foreign systems. This approach has been facilitated by COCOM's dissolution and the resulting international relaxation of controls on machine tool exports.

Since the end of COCOM in March 1994, PRC military industries have acquired advanced machine tools that would be useful for the production of rocket and missile guidance components, and several five-axis machines for fighter aircraft and parts production. Five-axis machines were controlled under COCOM and are purportedly controlled by Wassenaar.19 U.S. industry sources note that:

China has proved able to buy [machine tools] from a variety of foreign makers in Japan and Europe. Between 1993 and 1996, fifteen large, 5-axis machine tools were purchased by Chinese end users - all fifteen were made by Western European manufacturers.

Furthermore, Shenyang Aircraft purchased twelve 5-axis machine tools [in 1997]. These machine tools came from Italian, German and French factories.20

In addition, the PRC may be enhancing its ability to produce advanced machine tools through license production arrangements with Western manufacturers.

Other countries developing nuclear weapons and missiles have also apparently benefited from the PRC's ability to acquire advanced machine tools on the world market. As one recent Defense Department assessment noted, the PRC's "recent aerospace industry buildup and its history of weapons trade with nations under Western embargoes makes this increase in key defense capacity of great concern." 21

The Clinton administration has determined that specific examples of this activity cannot be publicly disclosed without affecting national security.

CASE STUDY: McDonnell Douglas Machine Tools

Findings of the U.S. General Accounting Office

The Select Committee has determined that the U.S. Government is generally unaware of the extent to which the PRC has acquired machine tools for commercial applications and then diverted them to military end uses.

he McDonnell Douglas case illustrates that the PRC will attempt diversions when it suits its interests.

At the request of Congress, the U.S. General Accounting Office in March 1996 initiated a review of the facts and circumstances pertaining to the 1994 sale of McDonnell Douglas machine tools to CATIC. The GAO issued its report on November 19, 1996.

The report can be summarized as follows:

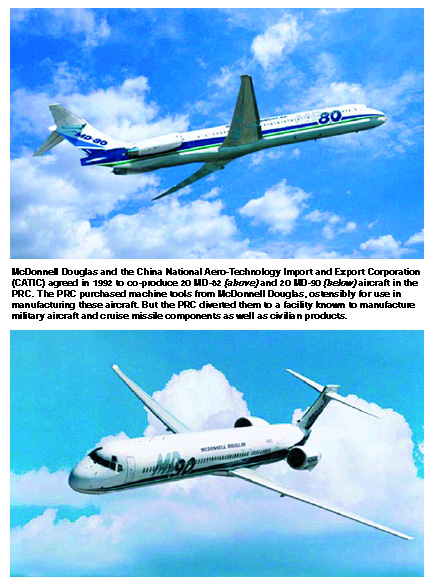

· In 1992, McDonnell Douglas and China National Aero-Technology Import and Export Corporation (CATIC) agreed to co-produce 20 MD-82 and 20 MD-90 commercial aircraft in the PRC. Known as the Trunkliner Program, the aircraft were to serve the PRC's domestic "trunk" routes. In late 1994, a contract revision reduced the number of aircraft to be built in the PRC to 20, and added the purchase of 20 U.S.-built aircraft.

· CATIC is the principal purchasing arm of the PRC's military as well as many commercial aviation entities. Four PRC factories, under the direction of Aviation Industries Corporation of China (AVIC) and CATIC, were to be involved in the Trunkliner Program.

· In late 1993, CATIC agreed to purchase machine tools and other equipment from a McDonnell Douglas plant in Columbus, Ohio that was closing. The plant had produced parts for the C-17 transport, the B-1 bomber, and the Peacekeeper missile. CATIC also purchased four additional machine tools from McDonnell Douglas that were located at Monitor Aerospace Corporation in Amityville, New York, a McDonnell Douglas subcontractor.

· The machine tools were purchased by CATIC for use at the CATIC Machining Center in Beijing - a PRC-owned facility that had yet to be built - and were to be wholly dedicated to the production of Trunkliner aircraft and related work. McDonnell Douglas informed the U.S. Government that CATIC would begin construction of the machining center in October 1994, with production to commence in December 1995.

· In May 1994, McDonnell Douglas submitted license applications for exporting the machine tools to the PRC and asked that the Commerce Department approve the applications quickly so that it could export the machine tools to the PRC, where they could be stored at CATIC's expense until the machining facility was completed. Following a lengthy interagency review, the Commerce Department approved the license applications on September 14, 1994, with numerous conditions designed to mitigate the risk of diversion.

· During the review period, concerns were raised about the possible diversion of the equipment to support PRC military production, the reliability of the end user, and the capabilities of the equipment being exported. The Departments of Commerce, State, Energy, and Defense, and the Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, agreed on the final decision to approve these applications.

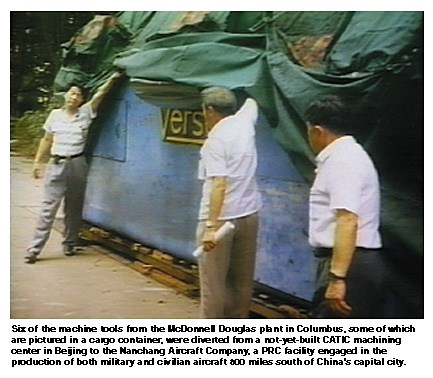

· Six of the machine tools were subsequently diverted to Nanchang Aircraft Company, a PRC facility engaged in military and civilian production over 800 miles south of Beijing. This diversion was contrary to key conditions in the licenses, which required the equipment to be used for the Trunkliner program and to be stored in one location until the CATIC Machining Center was built.

· Six weeks after the reported diversion, the Commerce Department suspended licenses for the four machine tools at Monitor Aerospace in New York that had not yet been shipped to the PRC. Commerce subsequently denied McDonnell Douglas's request to allow the diverted machine tools to remain in the unauthorized location for use in civilian production. The Commerce Department approved the transfer of the machine tools to Shanghai Aviation Industrial Corporation, a facility responsible for final assembly of Trunkliner aircraft. The diverted equipment was relocated to that facility before it could be misused.

· The Commerce Department did not formally investigate the export control violations until six months after they were first reported. The U.S. Customs Service and the Commerce Department's Office of Export Enforcement are now conducting a criminal investigation under the direction of the Department of Justice.22

The U.S. Government's Actions

in Approving the Export LicensesOn December 23, 1993, the China National Aero-Technology Import and Export Corporation (CATIC) reached an agreement to purchase machine tools from McDonnell Douglas. CATIC officials signed the purchase agreement with McDonnell Douglas on February 15, 1994.

A May 27, 1994 e-mail message to Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Export Administration Sue Eckert from Deputy Assistant Secretary for Export Administration Iain Baird noted:

We received 23 applications covering all of the material involved in this project two days ago. [McDonnell Douglas] plans on shipping to CATIC.

We have a long history with CATIC, which has been the consignee on numerous occasions - approved and denied based on licensing policies in effect at the time. CATIC was also the entity that attempted to buy the Machine Tool plant in the Northwest that was "denied" under the CFIUS process.

. . . .

Because of the sensitivity of this case, I think we should get it

to the ACEP [Advisory Committee for Export Policy] ASAP. We are going to suggest to the other agencies that we forgo the 60-90 [day] review process and, instead, bring together all the relevant experts in a special [Operating Committee] meeting in 2-3 weeks to make a recommendation.If it is not agreed to approve the transaction at that point (and it won't be),

we'll get the issue before the next ACEP.Stay tuned. 23

Subsequently, according to a June 8, 1994 memorandum to Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Counterproliferation Policy Dr. Mitchel Wallerstein from Acting Director of the Defense Technology Security Administration Peter Sullivan:

An interagency meeting was held 7 June 1994. Defense, State and Commerce were in attendance; Energy and CIA were invited but did not attend.

McDonnell Douglas representatives outlined their proposal. They would like closure on their license applications by 5 July 1994.

The possibility of meeting that request seems remote. First, initial staffing within DoD was accomplished 7 June 1994, when we received the required documentation from Commerce. Second, all parties agree that the prospects for escalation within the [U.S. Government] seem high, due to the scope of the proposed program, and the precedence [sic] it may establish. We will keep you informed of additional developments.24

Within the Defense Department, the McDonnell Douglas license applications were a cause of concern and internal debate. Specifically, the uniformed military services (Joint Staff) initially recommended denial.

The Joint Staff based its recommendation of denial upon an analysis indicating a high probability that this technology would be diverted for PLA end use.25 Moreover, the Joint Staff noted that, "Even with DoD recommending approval with conditions, this would be a less-than-prudent export to the PRC. This is particularly true in light of Chinese involvement in the world arms market."

The Staff of the U.S. Commander in Chief, U.S. Pacific Command, agreed, noting in an August 1, 1994 memorandum to the Joint Staff that it "concurs with the Joint Staff position to deny"

The Licensing Officer at the Defense Technology Security Administration who was initially assigned responsibility for the McDonnell Douglas license applications also recommended denial. The Licensing Officer reiterated concerns as to CATIC's role in both civilian and military production, and stated that "[n]o quantitative data has been supplied by the exporter, which establishes a clear need for this equipment in China [the PRC]."

Intelligence Community Assessments

Because of concerns that the McDonnell Douglas machine tools would give the PRC manufacturing production capabilities in excess of what was required for the Trunkliner Program, the Department of Defense asked for information that would assist it in determining whether these machine tools could be diverted to production of PLA military aircraft.A July 27, 1994 Defense Intelligence Agency response to a request from the Defense Technology Security Administration provided an assessment.26 It warned that, while similar machine tools were available from foreign sources, there was a significant risk of diversion. There was also the additional risk that the PRC could reverse-engineer the machine tools, and then use them in other commercial or military production. This would be consistent with the PRC's practice of reverse-engineering other Western technology for military purposes.

On August 9, 1994, the Defense Intelligence Agency provided a supplemental report explaining the results of its thorough assessment of the applicability of the McDonnell Douglas machine tools to three known PLA fighter aircraft programs, each of which incorporated stealth technologies. The report concluded:The establishment of an advanced machine tool facility presents a unique opportunity for Chinese military aerospace facilities to access advanced equipment which otherwise might be denied.

Similarly, placing these machine tools in one facility would reduce the financial outlay needed to acquire duplicate advanced machine tools for multiple military aircraft programs.

DIA . . . maintain[s] that the production capacity resulting from the McDonnell Douglas sale is above and beyond the requirement necessary for exclusive production of 20 MD-82 and 20 MD-90 McDonnell Douglas [aircraft], which is the stated end use in the export license application.

In fact, recent press reporting indicates China [the PRC] has dropped plans to build 20 MD-82s and will limit future production to just 20 MD-90 aircraft.27

The Defense Technology Security Administration had received information from informants in September 1993 - prior to CATIC's agreement to purchase the machine tools, and a full year before the license was granted - that CATIC personnel had visited McDonnell Douglas's Columbus, Ohio plant and videotaped the machine tools in use, a potentially illegal technology transfer.

The Defense Technology Security Administration reported the information to the U.S. Customs Service, and its agents later paid a visit to the Columbus, Ohio plant. However, following the visit, the U.S. Customs Service determined that no further investigative action was warranted.

During the interagency licensing process for the machine tools, the Defense Technology Security Administration also sought assessments from the Central Intelligence Agency and from the Defense Intelligence Agency, because of concerns that the PRC could use the McDonnell Douglas five-axis machine tools for unauthorized purposes, particularly to develop quieter submarines. Since the PRC wishes to enhance its power projection capabilities and is making efforts to strengthen its naval forces, the five-axis machine tools could easily be diverted for projects that would achieve that goal.

The Defense Technology Security Administration received additional information from informants indicating that CATIC had provided the Shenyang Aircraft Factory, an unauthorized location, with a list of the Columbus, Ohio equipment that had been purchased from McDonnell Douglas.28 Circles around some of the items on the list, according to the translation of a note from Shenyang that accompanied the list, indicated that the Shenyang Aircraft Factory was interested in obtaining those items from CATIC.

The Shenyang list was reportedly obtained from the discarded trash at a CATIC subsidiary in California.

This list was viewed as proof that CATIC intended to divert the machine tools to unauthorized locations. These concerns were reported to the U.S. Customs Service in the summer of 1994.

Changes to the Trunkliner Program

When McDonnell Douglas applied for export licenses on May 26, 1994, the applications noted that the machine tools would be used by the Beijing CATIC Machining Center primarily for the Trunkliner program. According to those license applications, McDonnell Douglas had a contract with CATIC to co-produce 20 MD-82 and 20 MD-90 aircraft.29In June 1994, McDonnell Douglas representatives provided a series of briefings to officials from the Commerce, State, and Defense Departments regarding the nature of the Trunkliner program and McDonnell Douglas's other activities in the PRC.30 In July 1994, however, Flight International magazine announced that the Trunkliner Program had been significantly changed.31

Instead of co-producing 20 MD-82 and 20 MD-90 aircraft in the PRC, only 20 MD-90 aircraft would be built there. Although the PRC would still acquire 20 additional aircraft, those would now be built at McDonnell Douglas's Long Beach, California plant - albeit with many parts that were to be fabricated in the PRC.

Prompted by the press reports, the Defense Department sought additional information from McDonnell Douglas in late July and early August 1994 regarding how the machine tools would be employed if the number of aircraft to be co-produced in the PRC was to be reduced.32

In letters to the Defense Technology Security Administration dated August 8 and August 12, 1994, McDonnell Douglas provided further clarification regarding the number and complexity of the parts that were to be manufactured in the PRC.

Commerce Department Licensing Officer Christiansen recalls that Commerce was not concerned that the number of aircraft to be co-produced in the PRC might be reduced, since parts for the aircraft would continue to be fabricated in the PRC.33

The Defense Technology Security Administration and the Defense Department, on the other hand, were concerned since they thought the machine tools might represent significant excess manufacturing capacity that the PRC might be tempted to divert to other, unauthorized uses.

The actual agreement that reduced the number of aircraft to be assembled in the PRC was signed on November 4, 1994.34

Discussions in the Advisory Committee for Export Policy

The McDonnell Douglas export license applications were discussed at the June 24, 1994 meeting of the Advisory Committee for Export Policy (ACEP).According to the minutes of that meeting, no decision was reached. The Defense Department representative at the meeting advised against approving the licenses that day, because internal Defense Department review was continuing. The Defense Department believed the applications could be approved if reasonable safeguards were put into place to prevent the machine tools from being used for unauthorized purposes.35

Among the other agencies in attendance, the State Department agreed with the Defense Department that further review was required. The Department of Energy deferred to the Defense Department on whether licenses should be approved.36

The license applications for the McDonnell Douglas machine tools were again discussed at a meeting of the Advisory Committee for Export Policy on July 28, 1994. Again, the matter was deferred until the next Advisory Committee meeting. The minutes reflect that "a final decision on this transaction would have to be remanded until the next meeting of the ACEP, or as soon as possible before that date, if all the agencies complete their reviews earlier."

According to the ACEP minutes, the respective positions of each agency on the applications were as follows:37

· [The Department of Defense] said that, if it had to vote at that time, it would recommend denial of the licenses because of concerns that the machine tools would be diverted. Moreover, there were concerns that the McDonnell Douglas machine tools would give the PRC excess production capacity, thus allowing other machine tools in its inventory to be diverted from civilian to military production.

· [The Department of] Energy indicated that, without further review, "it would have to defer to Defense in denying this transaction and the underlying applications."

· [The Department of] State recommended approval, provided that appropriate safeguards and conditions could be formulated to minimize the risk of diversion.

· [The] Arms Control and Disarmament Agency agreed with DOD [the Defense Department]'s position, noting that it would recommend denial of the license applications should it have to vote at that time.

· [The Department of] Commerce recommended approval with conditions to minimize the risk of diversion to unauthorized uses.

The License Is Issued

The Advisory Committee member agencies later agreed to issue the export licenses with 14 conditions.38Those conditions required, among other things, that:

· The machine tools were to be stored in one location pending completion of the Beijing CATIC Machining Center

· McDonnell Douglas was to provide quarterly reports to the Department of Commerce and the Defense Technology Security Administration should the Beijing CATIC Machining Center not be completed when the machine tools arrived39

As a final part of the licensing process, a Department of State cable was sent to the U.S. Embassy/Beijing on August 29, 1994 requesting that a senior CATIC official provide a written end use assurance that the machine tools would only be used for specified purposes.40

In a September 13, 1994 response, the U.S. Embassy/Beijing reported that it had obtained the assurance from CATIC Deputy Director Sun Deqing. However, the cable also noted that Deqing had indicated to the embassy officials that:

CATIC plans to establish several specialized factories under their new CATIC Machinery Company, and that [the CATIC Machining Center] would be one of those plants. [The CATIC Machining Center] will be established either near Beijing . . . or in Shijianzhuang at the Hongxing Aircraft Company . . .41

McDonnell Douglas's Limited Role at the Machining Center

Although McDonnell Douglas was planning to place up to four of its employees at the Beijing CATIC Machining Center, this was not to occur until late 1995 at the earliest.

Moreover, the Machining Center was not to be a joint venture between CATIC and McDonnell Douglas. Rather, it was to be a CATIC facility that supported CATIC's responsibilities to the Trunkliner Program.Trunkliner Program

Media reports indicated in July 1994 that McDonnell Douglas and the PRC were engaged in negotiations over the number of Trunkliner aircraft to be assembled in

the PRC.42Notes from a June 7, 1994 briefing that McDonnell Douglas provided to U.S. Government officials regarding its license applications indicate that McDonnell Douglas's representatives made references to the fact that the company was negotiating with the PRC over changing the mix of aircraft to be built in the PRC.43 CATIC was to remain responsible for the fabrication of large numbers of parts both for the aircraft that would be assembled in the PRC, and for the aircraft that were to be built in the United States under an "offset" agreement.

When queried by DOD officials regarding the continued PRC need for the machine tools in light of possible changes to the Trunkliner program, McDonnell Douglas responded in an August 8, 1994 letter to Defense Technology Security Administration Acting Director Sullivan. The letter provided further explanation regarding CATIC's proposed use of the machine tools. A subsequent August 12, 1994 McDonnell Douglas letter to the Defense Technology Security Administration's Colonel Henry Wurster noted:. . . The PRC factories that are participating in the Trunk Aircraft Program . . .do not have the capability individually, nor collectively, to accomplish the work share the PRC has agreed to (75 percent of the airframe) . . . If the licenses are denied, the PRC would purchase these types of machines somewhere else . . .

Commerce Department Delays Investigating

Machine Tool Diversion for Six MonthsThe Commerce Department's Actions in April 1995

As part of the licensing conditions for the machine tools, the machines tools were to be stored in one location pending completion of the Beijing machining center, and McDonnell Douglas was required to ". . . notify the [U.S. Government] of the location of the machine tools and update the [U.S. Government] with any changes of location prior to plant completion."In April 4, 1995 letters to the Commerce Department's Office of Export Enforcement, Washington Field Office, and to the Technical Information Support Division/Office of Exporter Services, McDonnell Douglas reported that the machine tools were located at four different places:

· Nine of the machine tools were located at two sites in the port city of Tianjin, a two hour drive from Beijing

· Four other machine tools had yet to be exported and were located at Monitor Aerospace Corporation in Amityville, New York

· Six machine tools were reported to be at the Nanchang Aircraft Company 44

According to the letters, a McDonnell Douglas employee had physically observed the machine tools in Tianjin, and confirmed that they remained in their original crates. He had not personally viewed the machine tools at the Nanchang Aircraft Company. However, the McDonnell Douglas letters reported that:

. . . CATIC did provide the attached letter to substantiate the list of equipment stored there. CATIC stated that the equipment has not been unpacked and remains in the original crates. [Emphasis in original]

The April 4 McDonnell Douglas letters did not trigger any kind of investigative response.

On April 20, 1995, an interagency meeting was held in which two McDonnell Douglas officials discussed the status and locations of the machine tools. The McDonnell Douglas officials reported that there had been changes in the number of aircraft that would be built jointly with the PRC, and changes in the location of the machine tools.

Since the machine tools were not stored in one authorized location, this violated the licensing conditions. McDonnell Douglas representatives responded by stating that the machine tools had inadvertently been moved to more than one location contrary to what had been specified in the export licenses, but that the building for the machine tools had not been completed and the tools had to be stored somewhere in the interim.

Six months later the Office of Export Enforcement received additional information from Commerce Department Licensing Officer Christiansen that, in conjunction with a formal request from the Defense Technology Security Administration, finally triggered the opening of a formal investigation into the diversion.

The Commerce Department's Actions in October 1995

An October 5, 1995 e-mail from Christiansen to a number of Commerce Department officials, including Office of Export Enforcement Acting Director Mark Menefee, reported that one of the six machine tools in storage at the Nanchang Aircraft Company had been uncrated, and was in the final stages of assembly.In clear violation of the export license, the machine tool - a hydraulic stretch press - had been installed in a building that apparently had been built specifically to accommodate that piece of equipment.

In his e-mail message, Christiansen stated:

For OEE [the Office of Export Enforcement], please investigate to determine who was responsible for both the diversion of the equipment originally and second who is responsible for the decision to install the equipment at Nanchang.

The formal request from the Defense Technology Security Administration for an investigation consisted of an October 4, 1995 letter from its Director of Technology Security Operations.45 The Defense Technology Security Administration informed the Acting Director of the Office of Export Enforcement, Mark Menefee, that:

During last week's ACEP [Advisory Committee for Export Policy] meeting a package of materials were handed out concerning the violation of McDonnell Douglas's export license to the Chinese.

The facts of the case are that CATIC has intentionally misused the export licenses to put controlled technology at a facility not authorized to receive [it].

This facility as confirmed by the Chinese is involved in the manufacture of both missiles and attack aircraft. I will be forwarding a copy of those materials to you separately.

We believe that this is a very serious matter and that the Office of Export Enforcement should conduct a serious investigation into this matter . . .

The Office of Export Enforcement determined that an active investigation was warranted, and opened a case file in early November 1995. The case was forwarded to the Office of Export Enforcement's Los Angeles Field Office for investigation because McDonnell Douglas Aircraft in Long Beach, California - the exporter of record for the machine tools - was located in the Los Angeles Field Office's area of responsibility.

Allegation that the Commerce Department

Discouraged the Los Angeles Field Office's Investigation

On June 7, 1998, the CBS program "60 Minutes" suggested that the Commerce Department or other U.S. Government entities were not necessarily interested in a complete and thorough investigation of the machine tool diversion. Among other things, the program included a brief appearance by Marc Reardon, a former Los Angeles Field Office special agent, who had initially been assigned to investigate the case. According to the official CBS transcript of the program:[CBS journalist Steve] KROFT: (Voiceover) And there's still some debate over just how hard the Commerce Department tried to find out who the bad guys really were. It took them six months to open an investigation. And Marc Reardon, the Commerce Department case agent assigned to investigate,

says higher ups in Washington didn't seem anxious to

get to the bottom of things.Did you feel like you were getting support from the department?

Mr. Marc REARDON: No. Not at all.

. . . .

KROFT: (voiceover) Reardon, who is now an investigator with the Food and Drug Administration, says he was told who to interview and what questions he could and couldn't ask.

Has that ever happened before?

Mr. REARDON: Not in my career.

KROFT: What did you make of it?

Mr. REARDON: That somebody didn't really want the

truth coming out.46The Select Committee conducted an investigation of these allegations. However, the Justice Department has requested that the Select Committee not disclose the details of its investigation to protect the Justice Department's prosecution of CATIC and McDonnell Douglas.

On February 5, 1996 U.S. News and World Report reported that the machine tools had been diverted, and that an investigation was underway. The Commerce Department received inquiries from then-Chairman Alfonse M. D'Amato of the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs, and from Chairman Benjamin A. Gilman of the House Committee on International Relations, concerning these reported allegations.47 Subsequently, Chairman Floyd D. Spence of the House Committee on National Security and Representative Frank Wolf asked the General Accounting Office to review the facts and circumstances relating to the licensing and export of the machine tools. The results of the General Accounting Office review are summarized earlier in this chapter.48

The February 5, 1996 U.S. News and World Report also claimed that "a confidential U.S. Commerce Department investigative report" had been obtained and used in the article. Concerned that the disclosure of such a report to U.S. News and World Report may have violated the confidentiality provisions of Section 12 (c) of the Export Administration Act, the Office of Export Enforcement initiated an internal inquiry. Responsibility for the disclosure was never determined.

The Office of Export Enforcement's Los Angeles Field Office's

Request for a Temporary Denial Order Against CATIC

Under the provisions of Part 766.24 of the Export Administration Regulations (EAR), the Assistant Secretary for Export Enforcement is authorized to issue a Temporary Denial Order (TDO):. . . upon a showing by [the Bureau of Export Enforcement] that the order is necessary in the public interest to prevent an imminent violation of the [Export Administration Act], the [Export Administration Regulations], or any order, license

or authorization issued thereunder.49In late November 1995, the Los Angeles Field Office requested that the Commerce Department issue a TDO against CATIC.50 The TDO request was prepared as a means to compel CATIC to comply with the terms of the machine tool export licenses by preventing the approval of future export licenses.

The Commerce Department declined to issue the TDO. In a December 7, 1995 memorandum, the Office of Export Enforcement Headquarters returned the TDO case report because it contained a number of technical deficiencies, including:

· Did not include licensing determination for each commodity that was exported. Licensing determinations were necessary elements of proof that the commodities required a license to be exported.

· Did not include any documentary evidence such as shipping and export control documents to confirm that the exports had occurred.

· Did not include a schedule of violations that described the specific violations that allegedly had occurred.

· Did not use the proper form and format that Office of Export Enforcement regulations specified in the Office's Special Agent Manual.

Headquarters, noted, however, that "the violations do appear to be deliberate and substantial." It instructed the Los Angeles Field Office to give the investigation a high priority. Moreover, it instructed them to conduct additional interviews and to obtain relevant documentation.

The Los Angeles Field Office was concerned that Headquarters was using those technical deficiencies as a bureaucratic rationale for not seeking Commerce Department approval of the TDO request.

At the date of the Select Committee's Final Report (January 3, 1999), the Office of Export Enforcement and the U.S. Customs Service reportedly are continuing to investigate the machine tool diversion under the direction of the U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia.

The PRC's Diversion of the Machine Tools

CATIC Letter Suggests Trunkliner Program at Risk

In a September 30, 1993 letter to McDonnell Douglas Aircraft Company President Robert Hood, CATIC Vice President Tang Xiaoping expressed concerns that negotiations were at an impasse for CATIC's purchase of the machine tools and other equipment.51 The letter seemed to suggest that the Trunkliner Program would be at risk if a deal could not be worked out. According to the letter:. . . I think for sure, whether or not this procurement project will be successful shall have a big influence on the trunk liner programme [sic] and long term cooperation between [Aviation Industries Corporation of China] and [McDonnell Douglas]. . .

McDonnell Douglas characterized Tang Xiaoping's letter as nothing more than a negotiating ploy to try to get McDonnell Douglas to lower the price that it was asking for the machine tools. McDonnell Douglas officials said they did not consider the letter to be a veiled threat by CATIC to cancel or alter the Trunkliner Program if a deal for the machine tool equipment could not be worked out.

According to the Defense Department, however, CATIC had a longstanding, productive relationship with McDonnell Douglas, had made major investments in the Trunkliner Program, and was not going to jeopardize those investments and the Trunkliner Program in a dispute over the price of used machine tools.

Indeed, the purchase price that was eventually agreed to between McDonnell Douglas and CATIC was acceptable to both parties. The value of the machine tools was based upon an appraisal provided by a commercial auctioneer. McDonnell Douglas added a 20-30 percent markup. CATIC acquired all of the machine tools it had originally sought, as well as various other tools, equipment, furniture and other items as part of the $5.4 million purchase agreement.

The machine tools and other equipment purchased by CATIC were excess to McDonnell Douglas's needs. According to McDonnell Douglas, the more modern machine tools and equipment from the Columbus, Ohio plant were not sold to CATIC but were redistributed to other McDonnell Douglas facilities.

According to the March 1, 1994 appraisal, the value of 31 machine tools sold to CATIC - including the 19 machine tools that required export licenses - was $3.5 million.52 This appraisal did not assess the value of other tools, equipment, and furnishings that were included as part of the purchase agreement.

CATIC's Efforts to Create the Beijing

Machining Center with Monitor Aerospace

Doug Monitto was the President of Monitor Aerospace Corporation, an Amityville, New York-based company that manufactured aircraft components. In the fall of 1993, Monitto met with CATIC representatives in the PRC to discuss joint venture opportunities.During those discussions, CATIC expressed an interest in subcontracting with Monitor Aerospace for the production of aircraft parts. Specifically, Monitor would assist the PRC in the production of certain aircraft parts that CATIC was to manufacture for Boeing as part of an offset contract.

Monitto says he proposed that CATIC convince Boeing to transfer $10 million of the offset work directly to Monitor for one year. During that year, Monitor Aerospace would assist CATIC in designing and laying out a new machining center.53

Thereafter, CATIC itself, with Monitor's assistance, could provide all subsequent manufacturing for the Boeing parts.Representatives of CATIC, Aviation Industries of China, and Monitto signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) regarding the machining center joint venture on January 24, 1994.54 CATIC officials took Monitto to an industrial park in Beijing where the machining center was to be built.

In a letter dated January 27, 1994, CATIC informed Boeing that it had signed the joint venture MOU, and asked if Boeing would consider providing Monitor Aerospace with the offset work.55 However, Boeing, in an April 1994 letter, declined CATIC's offer.56

In the spring of 1994, Monitto says CATIC officials again approached him about a machining center joint venture.

Although negotiations were intermittent, Monitto says CATIC informed him in the summer of 1994 that it had purchased machine tools from McDonnell Douglas. As Monitto recalls, CATIC officials asked for his assistance in reassembling the machine tools, and placing them in a machining center. However, he says the precise location of the machining center had not been determined at that time.57

A July 29, 1994 letter from Monitto to Sun Deqing, CATIC's Deputy Director, states:

As a result of your visit we have prepared an alternative approach that will help us achieve our mutually desired goal of building a "State of the Art" profile milling machine shop in China.

Monitor Aerospace would like to offer its assistance to CATIC in entering this new marketplace as both a partner and as a technical expert in the field.

The most significant feature of this new approach would be the fact that Monitor would also be the launch customer of the new joint venture.58

Additional discussions between CATIC and Monitor Aerospace regarding establishing the machining center appear to have continued into the fall of 1994, after the export licenses for the McDonnell Douglas machine tools had been approved.

According to a September 23, 1994 letter to CATIC's Sun Deqing, Monitto proposed that, as part of a joint venture to manufacture aircraft parts in the PRC, CATIC would:

. . . supply an appropriate building located in the Beijing-Tianjin metropolitan area which permits growth. CATIC will provide other necessary infrastructure and planning support, including arranging for appropriate utility hook-ups, tax concessions, customs clearance, etc.59Sometime in the fall of 1994, Monitto recalls that CATIC informed him that it intended to place the McDonnell Douglas machine tools at a facility located in the city of Shijiazhuang. Monitto drove to the facility to check out the offer but decided the location was too far from his base of operations in Beijing to be viable. It was "not something I wanted to do," Monitto comments.60

According to Monitto, he has had no further substantive discussions with CATIC regarding the establishment of a machining facility, although he does remain in contact with CATIC on other business-related matters. According to Monitto, McDonnell Douglas was never a party to any of his negotiations with CATIC regarding the establishment of the machining center.61

According to McDonnell Douglas, the first indication it had that CATIC would not establish the machining center took place during a phone call with a CATIC official in May 1995. Subsequently, in a letter dated July 5, 1995, CATIC Supply Vice President Zhang Jianli formally advised McDonnell Douglas that an agreement could not be reached with Monitor Aerospace for a machining center, and that Nanchang Aircraft Factory was interested in purchasing the six machine tools that were stored at that factory.

According to the letter:

You were aware that we planned to set up a joint venture with Monitor Aerospace, which would be the enduser [sic] in applying [for] the license. Unfortunately both sides couldn't reach agreement. Without this agreement we muse [sic] find other uses or purchasers in China. 62

According to McDonnell Douglas, it believed that CATIC was serious in its plans to build a machining center in Beijing to produce airplane parts for the Trunkliner Program.

McDonnell Douglas acknowledges, however, that it never asked for, nor was it shown, architectural drawings, floor plans, or other information to indicate that plans for the facility were progressing.

Diversion of the Machine Tools to Nanchang Aircraft Company

When the machine tools arrived in the PRC, McDonnell Douglas personnel discovered that nine of the machines were stored at two different locations in the port city of Tianjin.63

Moreover, a March 27, 1995 letter from Zhang Jianli, the Vice President of CATIC Supply Company, to McDonnell Douglas's Beijing office explained that six more of the machine tools had been shipped to Nanchang for storage. These machine tools, CATIC represented, remained in their crates.64

Two McDonnell Douglas representatives visited Nanchang to inspect the tools on August 23, 1995 and learned that one of the machine tools - a hydraulic stretch press - had been uncrated and was situated inside a building. Moreover, the building had been built specifically to accommodate that piece of equipment.

Although electrical power had not yet been connected,65 the size of the building and the manner of its construction suggested to them that this facility had been custom built to house McDonnell Douglas equipment, and had been planned for several years:

· Possibly as early as December 23, 1993, when CATIC and McDonnell Douglas signed an agreement for the purchase of machine tools and other equipment from McDonnell Douglas's Columbus, Ohio plant

· Perhaps even as early as late 1992, when CATIC first expressed interest in the purchase

CATIC (USA) documents66 indicate that an official of "TAL Industries" was primarily responsible for supervising the PRC team that coordinated and supervised the packing and crating of the machine tools and other equipment at the Columbus, Ohio plant.67 According to its responses to a series of Select Committee interrogatories, TAL Industries is a subsidiary of CATIC Supply in the PRC. CATIC Supply, in turn, is a wholly-owned subsidiary of CATIC.68 According to TAL Industries, CATIC Supply owns 90 percent of its stock, and CATIC (USA) owns the remaining 10 percent.69 TAL Industries is located at the same El Monte, California address and has the same telephone number as CATIC (USA).70

Some of the McDonnell Douglas equipment had been sold or given by CATIC to the Nanchang Aircraft Company. At least some of these transfers of ownership must have occurred before any of the equipment was exported from the United States. In addition, the PRC team that coordinated the disassembly and packing of the equipment at the Columbus, Ohio plant included representatives from the Nanchang Aircraft Company, who apparently were responsible for overseeing the packing of the equipment it was obtaining from CATIC.

Internally, CATIC specifically referenced the cargo as Nanchang's equipment.

Separately, the Nanchang Aircraft Company's Technology Improvement Office submitted inquiries to CATIC concerning the location of various pieces of its-Nanchang's-equipment.

Since most of the Columbus, Ohio equipment that was purchased by CATIC did not require an export license,71 CATIC's subsequent sale of that equipment to Nanchang Aircraft Company would not violate U.S. export controls.72 But the CATIC (USA) documents pertaining to Nanchang Aircraft Company's equipment do not explicitly identify the equipment, including the six machine tools that were later found at the Nanchang Aircraft Factory in violation of the export licenses.73

Nanchang Accepts Responsibility

In a September 13, 1995 letter to McDonnell Douglas China Program Manager Hitt, the Vice President of the Nanchang Aircraft Company accepted full responsibility for uncrating and installing the hydraulic stretch press in a newly constructed building. According to the letter:

Now I would like to review the detail and apologize for the result caused by the action we made. The following is the reason why we put the [hydraulic stretch] press into the pit.

When we heard that the agreement had not been made between CATIC and Monitor [Aerospace] concerning the cooperation. [sic] We expressed our intention to CATIC that we would like to buy some of the machines and at that time CATIC also intended to sell to us.

But they mentioned to us for several times that the cases can not be unpacked until the amendment of enduser [sic] is gained from the Department of U.S. Commerce. We do not think that there is any problem to get the permission for the second hand press, which has not got new technology because we have the experience that when we import the press from [a foreign manufacturer of machine tools].

Under this guidance of the thought, we started to prepare the fundation [sic] in order to save time.74

The letter went on to argue that, because of its size, the hydraulic stretch press had to be uncrated in order to move it to Nanchang from its port of entry in Shanghai. Moreover, the stretch press had then been moved into the "pit" that it would occupy so the new building could be built around it. To do otherwise, the PRC letter said, would have disrupted the construction of the new building.75

The Nanchang Aircraft Company official also apologized for the events that had occurred, and provided assurances that no further installation of the hydraulic stretch press would take place at the Nanchang Aircraft Factory until permission to do so was given by the U.S. Government.76

A July 5, 1995 letter to McDonnell Douglas China Program Manager Hitt from CATIC Supply Vice President Zhang Jianli reflects CATIC's knowledge that prior U.S. Government approval for the transaction was required. According to the CATIC Supply letter:

Nanchang Aircraft Factory is very much interested in 6 sets of the equipment. We would like to sell to them if we are allowed to do so because we understand that the licenses are only good for the Beijing machining center as it was approved originally.

Is it possible to request the United States Commerce department [sic] to approve selling the machines to Nanchang Aircraft Company? The machines are being stored there now, and they are required not to be unpacked until we receive approval from the Department of Commerce of the U.S.A.77 [Emphasis added]

When Hitt and a colleague visited the Nanchang Aircraft Company on August 23, 1995, the Nanchang Aircraft Company officials informed them that one of the machine tools delivered to Nanchang had been placed inside a building "to protect it from the elements."

At the insistence of McDonnell Douglas's Hitt, the PRC officials took him to the building, where he found a hydraulic stretch press installed in a building that appeared to have been specifically built for it. The building had actually been built around the hydraulic stretch press, since Hitt observed no openings or doorways that were large enough to have allowed the machine tool to be moved into the building from elsewhere. Parts for the machine were strewn about the building in such a manner as to indicate that efforts were underway to reassemble the machine and restore it to operational condition. Although electrical power had not been connected to operate the stretch press, trenches for the power cables had been dug and other electrical work had been completed.

Hitt says the storage explanation he originally was given by Nanchang officials was, without question, disingenuous.

Concerned over Hitt's expressions of anger at seeing the partially installed stretch press, Hitt says Nanchang officials tried to reassure him that they only intended to use the stretch press for civilian production at the factory.

Since early 1996, the McDonnell Douglas machine tools have been stored at Shanghai Aviation Industrial Corporation (SAIC).

Chronology of Key Events

1992 March 28 McDonnell Douglas and CATIC sign contract to co-produce 20 MD-82 and 20 MD-90 series commercial aircraft in the PRC. 1993 September Informants tell Defense Technology Security Administration that PRC nationals are regularly visiting McDonnell Douglas's Columbus, Ohio plant. Concerned that the visits may constitute illegal technology transfer, DTSA contacts U.S. Customs Service. September 30 Letter from CATIC Executive Vice President Tang Xiaoping to McDonnell Douglas Aircraft Company President Robert Hood suggesting that McDonnell Douglas's failure to sell machine tools to CATIC could have a "big influence" on Trunkliner Program. October 13 U.S. Customs Service agent visits Columbus, Ohio plant. Following interviews with McDonnell Douglas officials, U.S. Customs Service agent reports that no further investigative action is contemplated. December 23 CATIC and McDonnell Douglas reach agreement on sale of machine tools and other equipment from McDonnell Douglas's Columbus, Ohio plant, and four machine tools located at Monitor Aerospace, in Amityville, New York. Included are 15 machine tools that require individual validated licenses. 1994 January 24 Memorandum of Understanding for CATIC Machining Center joint venture signed by Monitor Aerospace, CATIC, and Aviation Industries of China. February 15 CATIC officials sign purchase agreement for machine tools and other equipment at McDonnell Douglas's Columbus, Ohio plant. March Disassembly, packing and crating of McDonnell Douglas machine tools and other equipment begins at Columbus, Ohio plant. Spring Defense Technology Security Administration learns that manufacturing equipment at McDonnell Douglas's Columbus, Ohio plant has been exported to the PRC. U.S. Customs Service

is informed.May 26 McDonnell Douglas applies for machine tool export licenses. June 7 McDonnell Douglas briefs Commerce, State, and Defense Department representatives on Trunkliner Program and CATIC Machining Center. June 23 McDonnell Douglas again briefs interagency meeting on Trunkliner program and CATIC Machining Center. June 24 Machine tool license applications discussed at Advisory Committee for Export Policy (ACEP) meeting. Defense Department cautions against rushing to approve licenses pending further review. No decision reached. July 26 Flight International article reports only 20 McDonnell Douglas aircraft to be built in the PRC, with the remaining 20 to be built in the United States. July 28 ACEP meeting again discusses machine tool licenses. Decision deferred until next ACEP meeting. August 25 ACEP meeting minutes indicate export licenses for the machine tools were approved prior to this ACEP meeting. August 29 State Department asks U.S. Embassy/Beijing to obtain end use assurance for machine tools from senior CATIC official. Late August Commerce Secretary Ronald Brown leads trade mission to the PRC. September 13 U.S. Embassy/Beijing reports that it obtained CATIC end use assurance and advises that final location of the machining center has not been determined. September 14 Department of Commerce formally issues export licenses to McDonnell Douglas for 19 machine tools. October Construction of machining center was reportedly to begin. November 4 CATIC and McDonnell Douglas sign amended contract reducing the number of aircraft to be built in the PRC from 40 to 20, with the remaining 20 to be built in the United States. November/

DecemberMost of Columbus, Ohio machine tools are shipped to the PRC. 1995 February Remaining Columbus, Ohio machine tools are shipped to the PRC. Four machine tools still remain at Monitor Aerospace in Amityville, New York. March 24 McDonnell Douglas representative inspects nine machine tools in original shipping crates at two locations in Tianjin, a port city two hours drive from Beijing. McDonnell Douglas's Beijing office letter to CATIC requests information on machine tools not found in Tianjin. March 27 CATIC letter to McDonnell Douglas's Beijing office assures that six machine tools remain packed and in storage in Nanchang. April 4 McDonnell Douglas letter to the Department of Commerce reports location of machine tools and notes that six of the machine tools are reportedly located at Nanchang Aircraft Company, four remain at Monitor Aerospace in Amityville, New York, and the remainder are stored at two locations in Tianjin. April 20 McDonnell Douglas briefs interagency meeting on locations of machine tools. Commerce Department Office of Export Enforcement representative is present at meeting, and determines that no active investigation is warranted. Late April/

Early MayIn telephone call with McDonnell Douglas China program manager, CATIC official says no agreement could be reached with Monitor Aerospace for creation of the machining center. The Department of Commerce is informed. May 15 The Department of Commerce instructs McDonnell Douglas to arrange for the six machine tools at Nanchang to be shipped to and consolidated with the nine machine tools at Tianjin. The Department of Commerce informs McDonnell Douglas that it has revoked the export licenses for the four machine tools at Monitor Aerospace in Amityville, New York. June 1 In a letter to CATIC, McDonnell Douglas requests CATIC take immediate action to consolidate all machine tools at one location in Tianjin, and informs CATIC that the Commerce Department has cancelled the export licenses for the four machine tools in Amityville, New York. July 15 Letter from CATIC to McDonnell Douglas confirms that no agreement could be reached with Monitor Aerospace to build the machining center, and that Nanchang Aircraft Factory was interested in purchasing six machine tools. The letter asks McDonnell Douglas to obtain U.S. Government approval for that transaction. August 1 McDonnell Douglas applies for Commerce Department licenses to allow six machine tools to remain at the Nanchang Aircraft Factory. August 23 During a visit to the Nanchang Aircraft Factory, McDonnell Douglas representatives discover the hydraulic stretch press uncrated and situated in a partially completed custom building designed and built around it. September 28 Commerce Department informs McDonnell Douglas to remain at Nanchang Aircraft Factory. October McDonnell Douglas requests amended export licenses to allow the machine tools at Tianjin and Nanchang to be moved to Shanghai Aviation Industrial Corporation for use in the Trunkliner program. November 7 Commerce Department's Office of Export Enforcement opens investigation of the machine tool diversion. November 28 The Office of Export Enforcement Los Angeles Field Office asks the Commerce Department to issue a Temporary Denial Order against CATIC. December 7 Office of Export Enforcement denies the request for a Temporary Denial Order against CATIC. December CATIC Machining Center in Beijing was reportedly to start producing Trunkliner parts. 1996 January 31 Commerce Department is informed that five of the six Nanchang machine tools have arrived at the Shanghai Aviation Industrial Corporation. The hydraulic stretch press remains at Nanchang. February 6 Amended licenses are approved by Commerce Department to permit the machine tools to be used by the Shanghai Aviation Industrial Corporation. Late Winter/

Early SpringU.S. Customs Service joins machine tool investigation. April 23 U.S. Embassy official visits Shanghai Aviation Industrial Corporation and examines the machine tools from Tianjin. June 21 Portions of the hydraulic stretch press from Nanchang are reported to be at Shanghai. July Marc Reardon, the Commerce Department Los Angeles Field Office case agent for the machine tool investigation, resigns. August 5 The remaining parts of the hydraulic stretch press from Nanchang are reported to be at Shanghai.

Chapter 10 Notes

1 "Report to Congress Pursuant to Section 1305 of the FY97 National Defense Authorization Act," Defense Intelligence Agency, April 1997.

2 "Current and Future Challenges Facing Chinese Defense Industries," John Frankenstein and Bates Gill, China Quarterly, June 1996; and Gearing up for High-Tech Warfare, Richard Bitzinger and Bates Gill, Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 1996.

3 "Current and Future Challenges Facing Chinese Defense Industries," John Frankenstein and Bates Gill, China Quarterly, June 1996.

4 Gearing up for High-Tech Warfare, Richard Bitzinger and Bates Gill, Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, 1996.

5 "Report on the Outline of the Ninth Five-year Plan for National Economic and Social Development and Long-Range Objectives to the Year 2010," Li Peng, Speech delivered to the Fourth Session of the Eighth National People's Congress on March 5, 1996.

6 "China: Domestic Change and Foreign Policy," Michael Swaine, The RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, California, 1995.

7 "Report to Congress Pursuant to Section 1305 of the FY97 National Defense Authorization Act," Defense Intelligence Agency, April 1997.

8 "Some Examples of Chinese Technology Targeting," from the Defense Intelligence Agency program brief ing on "Project Worldtech," no date; and China's Aerospace Industry, Jane's Information Group, 1997.

9 Department of Defense, The Militarily Critical Technologies List. Part I: Weapons Systems Technologies (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Defense, June 1996).

10 Defense Department report, February 1996.

11 Export Administration Regulations, Section 399.1, Supplement No. 1, Group 0, ECCN 1091A, January 1, 1986.

12 Export Administration Regulations, Part 774, Supplement No. 1, ECCN 2B001.

13 Export Administration Regulations, Part 738.4.

14 Export Administration Regulations, Part 774, Supplement No. 1, Category 2, Group B.

15 Export Administration Regulations, Part 774, Supplement No. 1, Category 2.

16 For example, the ECCN for numerically controlled machine tools is 2B001. The first "0" denotes that the reason for the control of machine tools with ECCN 2B001 is for national security reasons as opposed to a "1" (missile technology), a "2" (nuclear nonproliferation), a "3" (chemical & biological weapons), or a "9" (anti-terrorism, crime control and other factors). The second "0" indicates that the reason for control is for multilateral vice a unilateral ("9") concern. Export Administration Regulations Part 738.2.

17 General Accounting Office, Export Controls: Sensitive Machine Tool Exports to China GAO/NSIAD-97-4, November 1996.

18 Department of Defense, The Militarily Critical Technologies List (Part I: Weapons Systems Technologies (Washington, D.C., Department of Defense, June 1996).

19 It was noted that this information is mostly anecdotal and far from comprehensive.

20 The Association for Manufacturing Technology, "American Machine Tool Producers Unfairly Burdened by U.S. Export Controls," 1998.

21 Defense Department report, 1996.

22 The machine tool diversion reportedly remains under investigation by the Department of Justice.

23 E-mail from Iain Baird to Sue Eckert, May 27, 1994.

24 Memorandum for Deputy Assistant Secretary for Counterproliferation Policy from Acting Director/DTSA, June 8, 1994.

25 Defense Department document, 1994.

26 Memorandum for the Director, Strategic Trade Policy, Defense, DTSA from Chief, Technology Transfer Branch, Nonproliferation and Arms Control Division, DIA, July 27, 1994.

27 Memorandum for Director, Strategic Trade Policy, Defense, DTSA from Chief, Technology Transfer Branch, Nonproliferation and Arms Control Division, DIA, Subject: Chinese Acquisition of U.S. Machine Tools, August 9, 1994.

28 CATIC Inventory Lists.

29 Attachment B to Export License Application #C771659.

30 McDonnell Douglas briefing charts, June 7, 1994.

31 Flight International Magazine, edition of 20-26 July, 1994.

32 Memorandum for the Record authored by Dr. Peter Leitner, Senior Strategic Trade Advisor, DTSA, Subject: Telecon w/Joyce Poetzl and Bob Hitt, July 26, 1994. Memorandum for Executive Secretary, ACEP from Colonel Raymond Willson, Acting Director, Licensing Directorate, DTSA, August 5, 1994.

33 Interview of Elroy Christiansen, October 19, 1998.

34 GAO Report, Export Controls, Sensitive Machine Tool Exports to China, November 1996.

35 ACEP Minutes from June 24, 1994.

36 Ibid.

37 ACEP Minutes from July 28, 1994.

38 Memorandum for Commerce Deputy Assistant Secretary for Export Administration Sue Eckert from Director DTSA Dave Tarbell, August 26, 1994.

39 Copies of McDonnell Douglas machine tool export licenses, September 14, 1994.

40 State Department cable 235206 to U.S. Embassy/Beijing, August 29, 1994.

41 U.S. Embassy Beijing cable 43102, September 13, 1994.

42 Flight International Magazine, edition of 20-26 July, 1994.

43 McDonnell Douglas Briefing Notes, June 7, 1994.

44 McDonnell Douglas letter to Office of Exporter Services/Technical Information Support Division, April 4, 1995. McDonnell Douglas Letter to Office of Export Enforcement, Springfield, VA, April 4, 1995.

45 Memorandum to Acting Director/OEE Menefee from DTSA/TSO, October 4, 1995.

46 CBS transcript, 60 Minutes program of June 7, 1998.

47 U.S. News & World Report, Vol. 120, No. 5, February 5, 1996. Letter to Undersecretary Reinsch from Senator D'Amato, February 23, 1996. Draft Commerce letter to Senator D'Amato, March 25, 1996. Representative Gilman letter to Reinsch, March 5, 1996.

48 General Accounting Office, Export Controls: Sensitive Machine Tool Exports to China GAO/NSIAD-97-4, November 1996.

49 Export Administration Regulations, Part 766.24(a).

50 Select Committee staff were afforded an opportunity to examine the TDO request, but Commerce officials declined to provide a copy of the document to the Select Committee based on a claim that the document contained law enforcement sensitive information regarding an active criminal investigation.

51 Letter to Douglas Aircraft Company President Robert Hood from CATIC Vice President Tang Xiaoping, September 30, 1993.

52 Appraisal, Williams & Lipton Company, March 1, 1994.

53 Telephone Interview of Douglas Monitto, October 20, 1998.

54 Telephone Interview of Douglas Monitto, October 20,1998. Memorandum of Understanding between CATIC, Monitor Aerospace and AVIC, January 24, 1994.

55 Letter to Lawrence W. Clarkson, Corporate Vice President, Planning and International Development, Boeing Company from Tang Xiaoping, Executive Vice President, CATIC, January 27, 1994.

56 Letter to Tang Xiaoping, from J.D. Masterson, Boeing Commercial Airplane Group, April 6, 1994.

57 Telephone Interview of Douglas Monitto, October 20, 1998.

58 Letter to CATIC Deputy Managing Director Sun Deqing from Douglas Monitto from Monitto, July 29, 1994.

59 Letter to CATIC Deputy Managing Director Sun Deqing from Douglas Monitto, September 23, 1994.

60 Telephone Interview of Douglas Monitto, October 20, 1998.

61 Ibid.

62 Letter to McDonnell Douglas China Program Manager Bob Hitt from CATIC Supply Vice President Zhang Jianli, July 5, 1995.

63 Letter to Office of Export Enforcement from McDonnell Douglas reporting location of machine tools, April 4, 1994.

64 Letter to John Bruns, Senior Manager, McDonnell Douglas Corporation Beijing Office, March 27, 1994.

65 Memorandum to Joyce Poetzl from John Bruns and R. J. Hitt, Subject: Inspection of Machine Tools at Nanchang Aircraft Manufacturing Company, August 26, 1995.