|

|||

|

|||

|

|

Space became part of the military environment with the use of V-2 rockets during World War II. With a range of about 220 miles (350 km), they reached altitudes of 60 miles (100 km). When the Soviet Union put its first Sputnik into earth orbit in October 1957, followed in January 1958 by the U.S.'s first Explorer, the occupancy of space — whether for civil or for military purposes — became a reality. Unmanned systems were soon followed by manned spacecraft; both types played roles during 30 more years of Cold War, as well as for more benign purposes. Military satellites were used for national intelligence purposes and for operational support missions; both types of activity were usually highly classified.

|

||

|

"Military space operations 'came of age' during the Persian Gulf War ..." |

Military Operations. Military space operations "came of age" during the Persian Gulf War of 1990-91, when used to support tactical operations vice solely strategic C3I. Historically, space systems had supported primarily strategic missions within a bi-polar Cold War context and at a national command level. Space products were highly classified, and their dissemination limited. One of the Gulf War's key outcomes was a broad recognition of the importance of space systems' contributions in a theater context, and from conditions of peace through crisis to hostilities and back again. The Gulf War itself was an outstanding success, and so were the space systems that supported it. From the unmatched precision of GPS-supported munitions to the tactical warning afforded by space-based missile sensors, our space systems worked just the way they were supposed to, and in many cases better — especially when one considers that many systems were not designed for regional conflict. However, what they did not do was work together. Surveillance satellites told us when an Iraqi Scud tactical ballistic missile was launched, but lacked the ability to give us precise coordinates. These were symptoms of a bigger problem: no one was charged with the responsibility to make sure everything worked together in a theater campaign. While the dedication and hard work of the people managing the systems got the job done, we identified areas for improvement. Moreover, as the Cold War ended and budgets began to shrink, we needed to find ways to do more with less. We also learned that the process for making intelligence available to combat commanders was also inadequate. Again, the channels for transmitting sensitive data from the "black" world to field commanders operating primarily in the "white" world were constricted, with the result that timely intelligence distribution to operational units was often a problem. Other Activities. In addition to a different operational environment for government space systems, commercial and foreign space technologies were improving, with the following results:

When combined with shrinking budgets, these forces also added pressures to reassess national security technology investments and operations with non-defense marketplace products.

|

||

|

"effective operations in this emerging world require the coordinated involvement of all space participants ..." |

Space Systems Acquisition. When the

government had a virtual monopoly on space system acquisition, the

tendency was to procure small numbers of systems designed to meet

critical Cold War requirements of specific users, with but secondary

regard for cost or competition. However, the 1990s defense-wide trend

toward a tactical/operational focus, more flexible and open architectures

to avoid "stovepiped" systems, consolidated acquisitions to meet joint

requirements and controlled costs all indicated that the DoD would have

to change the way it was "doing business" if the U.S. were to retain its

space leadership and continue to support evolving post-Cold War national

policies.

The space world is changing so fast that new, unconventional, "out-of-the-box" approaches are required. Essentially, national security space capabilities are needed for a changing world in which:

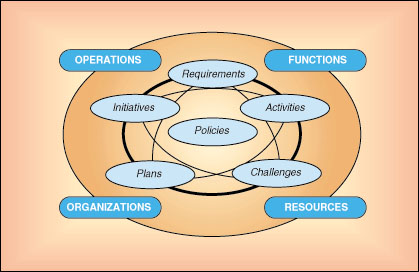

It became increasingly apparent to both the Congress and the Defense and Intelligence Communities that effective operations in this emerging world require the coordinated involvement of all space participants, both military and civil. The steady change on all fronts requires a centralized approach that will manage multiple variables in the face of uncertainty, as suggested in the graphic below. DUSD(S)'s role is to "reengineer space" — in the sense of how we will "do space business" in the national security arena and how we will implement the National Space Policy approved by the President in 1996. In pursuing this course, we seek the continued cooperation of the space community as we move forward.

The Management Challenge: Interactions of Space |

||

|

|||

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|

The U.S. government no longer "drove" the space technology market in many

areas; and

The U.S. government no longer "drove" the space technology market in many

areas; and