|

|||

|

|||

|

|

Space has often been referred to as "the high ground," in the sense of giving its occupier a dominating view (and prospective control) of a potential battlefield. Today it is a key operating régime within the Joint Staff's Intelligence, Reconnaissance and Surveillance (ISR) functional assessment area. Traditionally, it has provided a global capability for three basic military functions:

|

||

|

"Space... is a key operating regime within the Joint Staff's...ISR... functional assessment area." |

Sensing - Determining what is "out there" in

the arena or battlespace of interest. This is key to the operational

space missions of environmental monitoring, warning and attack assessment,

reconnaissance and MC&G. Sensing - Determining what is "out there" in

the arena or battlespace of interest. This is key to the operational

space missions of environmental monitoring, warning and attack assessment,

reconnaissance and MC&G.

To support these three functions in space, we need to get them there in the first place and then manage, support, control and exploit them once there. We do this via the following generic functions:

|

||

|

"Half our space program's budget — and all its people — go to space systems' surface compo- nents for...O&S ...activities and facilities." |

USSPACECOM, as operator, focuses on the operational

aspects of these functions while the Services (principally the Air Force,

as executing agent for most of the DoD's space programs) provide, equip

and train the forces that perform and support them. Half our space

program's budget — and all its people — go to space systems'

surface components for operations and support (O&S) activities and

facilities. These operations are essential, and they are expensive. Our perspective is both supportive and future-oriented: how to perform end-to-end space activities better and cheaper — to include determining whether they should be performed by different means or even not at all. Therefore, DUSD(S) views space systems differently from the user, or "customer," to whom they represent capabilities in an operating environment. These differing perspectives are depicted below.

DUSD(S) and User Perspectives on Space Systems

The DUSD(S)'s Space Community

|

||

|

"... DUSD(S) is the DoD's space representative in a highly complex and dynamic interagency environment." |

In addition, DUSD(S) is the DoD's space representative

in a highly complex and dynamic interagency environment.

Interdepartmental and international initiatives require significant

attention. In turn, each activity offers new challenges to our space

programs and how we do business. This interagency working environment is

illustrated above. The leverage and popularity of our defense space capabilities are indicated by the range of "players" represented in the graphic. For several years, government space capabilities have also been used to foster civil and commercial initiatives, particularly in communications, sensing, and use of DoD launch facilities. Commercial markets have in turn been shaping advanced technology arenas where defense needs had previously ruled. Today, the growing number of space-faring nations offers us both opportunities and challenges. The following examples illustrate the trends.

Use of Launch Facilities For over a decade, the Commercial Space Launch Act and national policy have mandated DoD support for U.S. commercial space activities. As executing agent, the Air Force has done a first-class job of maintaining America's access to space — not just for national security missions, but for civil and commercial activities as well. The Air Force finalized a policy that addresses critical competition issues associated with increasing commercial use of government launch property and defines processes for use of launch ranges. Thus, like other space capabilities developed initially for national security purposes, our launch capability has become a broader national asset. Furthermore, the law requires the DoD to provide this launch support at marginal cost only; i.e., we charge commercial users only what it costs us directly to provide the launch and range support. In June of last year, we testified to this effect before the House Committee on Science's Subcommittee on Space and Aeronautics, and also noted how we were taking steps to meet the challenge presented by our (and the commercial sector's) success. The challenge arises from the annually increasing ratio of commercial to government launches and their budgetary impacts. Specifically, commercial launches from Cape Canaveral, FL, outnumbered DoD and NASA launches starting in 1995, and they will outnumber DoD and NASA launches from Vandenberg AFB, CA, during 1997. We further project that commercial launch requirements (to deploy and sustain new commercial satellite constellations providing worldwide messaging, voice and data communications and remote sensing) over the next five to ten years will continue to outnumber government launches. Our dilemma is that reimbursements for our direct operating costs do not allow for sustainment and modernization of our launch infrastructure, which will continue to benefit commercial interests as much or more than its government owners. The following table projects these overhead and investment costs.

|

||

|

"... reimbursements for our direct operating costs do not allow for sustainment and modernization of our launch infrastructure ..." |

DUSD(S) Approach. The DoD's efforts to both fulfill its federal role and meet the launch challenges are threefold:

The EELV program is aimed at reducing the cost and preparation time for launch — for both government and commercial missions. Payload, standards and launch range working groups, with participation by the commercial satellite industry as well as federal agencies, are assuring that all user needs are considered in the development of the launch vehicle, its facilities, and existing ranges. This $2 billion program will provide a family of modernized launchers with reduced operating costs. The National Spacelift Requirements Process (NSRP) is seeking consensus among civil, commercial, defense and intelligence space sectors on common spacelift needs. Its resulting document will contain top-level requirements usable in the development or modification of any national launch system capability. Annual review of this document by the National Spacelift Requirements Council (representing DoD, DOC, NASA, and the Federal Aviation Administration's (FAA's) Office of Commercial Space Transportation) will keep it current. The DoD (especially the Air Force) has already played a pivotal role in bringing spaceports to life as a new element of the U.S. commercial space sector. The Air Force Dual Use Space Launch Infrastructure Grant Program jump-started infrastructure development projects by providing $20 million in matching funds (on a 3:1 federal-to-industry basis) for spaceport construction projects, other commercial infrastructure projects, and related studies in FY 1993 and 1994. Several diverse spaceport projects are underway today, including projects for a variety of new small launch vehicle processing and launch facilities in California, Florida, Alaska, and New Mexico. On the DoD side, we are examining the potential of commercially operated launch sites to help support government launch programs, especially for small payloads. In 1996, the SecDef approved the demonstration flight of a converted Minuteman II missile to evaluate the concept and costs of using them as launchers. If this initiative succeeds, commercial spaceports could provide a lower-cost alternative for small payloads. In March 1996, we formed an Interagency Working Group to develop federal guidelines for government interaction with commercial spaceports. Participation included my office (co-chair), the Army, Navy, Air Force, Joint Staff and USSPACECOM from DoD, and the FAA (co-chair), NASA, DOC and DOS. Once in place, these guidelines will enable each federal agency to develop implementation guidelines for interacting with launch site operators and also offer a basis for joint responses to proposed changes to national policy or law. Meanwhile, we continue to address the increasing stress of commercial activity on our own launch capabilities — especially as we are funded only for our national security activities. We are looking into the potential of fee-for-service and increased contractor participation at launch sites, so that we can recover more of our investment, and thereby achieve a more equitable sharing of launch infrastructure costs. The loss of a GPS satellite aboard a Delta II booster this past January — the first launch failure in over a year — showed once again how dependent the space community is on ready, reliable launch for timely space access. The bottom line is that we have a long and successful role in supporting the commercial space sector and helping it compete in the world market. For 1997 and on, we also need to restructure our government launch capability to sustain our assured access to space for defense.

of Commercial Practices For several years now, the DoD has been "changing its culture" with respect to systems acquisition. Based on both market forces and the need for acquisition reform, the Department has been expanding its use of commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) products, commercial in lieu of military specifications (MILSPECs) and standards, and adoption of commercial "best practices" in contracting and project management. We are looking more and more for commercial space solutions and partnership with industry, partly because DoD is a decreasing factor in the overall space market and partly to save defense R&D money for key military capabilities. In short, the space acquisition and support environment has evolved radically. Industry is more of an equal partner in many areas, and a leader in even some critical areas, like electronics, where the commercial market dominates. The scope of partnership exchange continues its needs to broaden:

The Services and the NRO, as program executing agents, are doing well in transitioning their business processes to incorporate more commercial products and practices. The use of joint government-industry IPTs, for example, also helps to assure that commercial and industrial factors are considered in a timely way throughout defense acquisition programs.

|

||

|

"We are looking more and more for commercial space solutions and partnership with industry ..." |

At the same time, specific attention must continue to

be paid to those items and practices that need to retain "defense"

features. Among them are specific components or capabilities relating to

system survivability, security, environmentally stressed performance, and

simplicity of operation and support. Rather than duplicate what industry

is already doing, we should adapt commercial products where practical

and focus our investment on critical national security capabilities,

features, and functions.

with Other Sectors Both before and after the 1996 National Space Policy's provisions, DoD assets have supported civil agency objectives or operations. Cooperative activities have involved DOC/NOAA, NASA, DOE and DOT on a continuing basis. Both national security and civil sensors and communications links have been used for space-based observations of the earth's land, atmospheric and oceanic conditions for both government and commercial purposes.

|

||

|

"NPOESS will be the nation's single source of global weather data for operational DoD and DOC use." |

National Polar-orbiting

Operational Environmental Satellite System (NPOESS). This

environmental sensing program combines the follow-on to the DoD's Defense

Meteorological Satellite Program (DMSP) and the DOC's Polar-orbiting

Operational Environmental Satellite (POES) under a tri-agency program

office. DOC is program lead, DOC and DoD share the funding, and NASA

contributes technology. NPOESS will be the nation's single source of

global weather data for operational DoD and DOC use. It will provide

force commanders and civilian leaders with timely, high-quality weather

information for the effective employment of weapon systems and to protect

national resources. NPOESS is a Presidentially directed program; however, as it transitions from Phase 0 into Phase I, our near-term challenge is to maintain participation and the program schedule in view of likely continuation of selected agency budget and staff downsizing efforts.

|

||

|

"With relatively inexpensive user equipment, [GPS's] accurate positioning capabilities have become a routine service for many operations." |

GPS Operations Global Positioning System (GPS). GPS was acquired and fielded from the start as a dual-use navigation system with initially military applications. The President's March 1996 GPS Policy sees its growing role within the Global Information Infrastructure, with applications ranging from mapping and surveying to international air traffic management and global change research, all of which have fed the worldwide growth of the U.S.'s $8 billion GPS equipment and service industry. Declared fully operational in 1996, GPS's constellation of 24 satellites has been providing positioning and location information to all types and levels of user, from deployed military units during the Gulf War to elementary school classes performing science experiments today. With relatively inexpensive user equipment, its accurate positioning capabilities have become a routine service for many operations.

|

||

|

"... the NASA- DoD AACB investigated areas for cooperation that could achieve significant cost reductions and enhanced mission effectiveness and efficiencies. " |

Domestically, our challenge is a product of our

success. The GPS Policy states our intention to discontinue GPS's

Selective Availability feature (designed to deny accuracy to

adversaries) within ten years; beginning in 2000, the President will

make an annual determination on its continued use. Meanwhile, commercial

users are achieving increased accuracy by coupling ground-based beacons

with GPS in a system called Differential GPS (DGPS). In addition, the

promulgation of GPS standard features and specifications for continuous

universal use raises the specter that enemies could use GPS capabilities

for their own purposes and/or against ours. The DoD, DOT, DOS and other agencies all have roles to play, both in managing GPS augmentations and in protecting the national interest. Our military is now planning to use a stronger, more jam-resistant GPS signal (called the Precision Code) to drown out competing GPS signals and counter enemy exploitation attempts on the battlefield. Aeronautics and Astronautics Coordinating Board (AACB). From June 1995 through May 1996, the NASA-DoD AACB investigated areas for cooperation that could achieve significant cost reductions and enhanced mission effectiveness and efficiencies. The seven IPTs and their areas of investigation included:

Each IPT presented its recommendations at the AACB's 99th meeting, in April 1996. The key fact is that savings and efficiencies are in addition to those identified over previous years.

International Space Cooperation Our international space interests are:

|

"The next generation ... MILSATCOM ... is our test case for cooperation to attain military interoperability." |

GPS. In accordance

with the

GPS Policy's international goals, the U.S. will:

Accordingly, the DoD is directed to:

Our domestic program initiatives will also support our international objectives. Communications. As communications are a key to the effective operations of joint and multinational forces, for the past several years, the DoD has called for international cooperation in military space programs. The next-generation military satellite communications system (MILSATCOM) is our test case for cooperation to attain military interoperability. At present, our French, German and British allies are planning to pursue an all-European option called TriMilSatCom — a four-satellite system with geostationary orbits whose space and ground components are estimated to cost $2.6 billion. The U.S. could then find itself in the position of having to invest in a national system to assure that its own military and civil requirements are met. While both U.S. and European governments are encouraging cost savings by acquiring each other's commercial subsystems, the opportunity for four-way cost savings via acquisition of a common system may be decreasing. At the same time, it would be mutually beneficial if we can participate in each other's programs in specific areas of expertise to avoid duplicating existing capabilities.

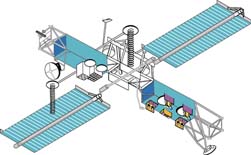

U.S. Milstar II We, like our allies, want to foster economic advantages for our industry, but not at the expense of major military benefits for all four nations (and other allies) as a whole. Our current challenge is to continue working in the international arena to encourage as much commonality and interoperability as our community of nations can attain.

|

"Our current challenge is ... to encourage as much commonality and interoperability as our community of nations can attain." |

Space-Based Infrared System

(SBIRS). Another goal we share with our allies for future

coalition operations is accurate and timely warning of enemy missile

launches. SBIRS is designed to replace DSP, which provided Scud launch

warnings during the Gulf War, with a dual scanning and staring sensor

configuration expected to improve on DSP's sensitivity and response time

by at least an order of magnitude. Last year, the Air Force let

contracts to develop the ground, high and low components of the SBIRS

program, and will contract in FY 1999 to build its low earth orbit (LEO)

component, the Space and Missile Tracking System (SMTS). Meanwhile, we have already offered our NATO allies access to missile warning data. For joint and coalition operations, it is highly desirable that all forces benefit from timely missile warning.

SBIRS Program

Radiation Hardening (Rad Hard) for Future Systems

|

"Defense space systems must be designed to operate in a higher threat radiation environment ... than commercial space systems." |

One of the inherently government functions in military

systems acquisition is to ensure the availability, reliability and

survivability of the fielded system. Defense space systems must be

designed to operate in a higher threat radiation environment and have a

higher degree of reliability and survivability than commercial space

systems. As the commercial market is now the "driver" of both product

design and manufacturing process decisions, DoD must determine if there

are and will be sufficient capabilities to meet national security space

systems' long-term needs for rad-hard microelectronics. Rad-hard

electronics also help reduce space systems' weight and power

requirements. Although near-term industrial capability is not endangered, rad-hard technology advances and production infrastructure have declined significantly in the past several years, due to an insufficient business and investment base for existing suppliers. Moreover, rad-hardening becomes more difficult with each new generation of microelectronics technology, and a significant knowledge-skill base is needed to meet the mix of "soft" and "hard" requirements for different systems' components. We recommend a combination of:

From the above selected examples, our DoD space programs, operations and initiatives are increasingly intertwined with commercial factors in the worldwide marketplace, civil agency programs and operations at home, and the policies and interests of other countries abroad — whether they are our allies or potential foes. Many hard choices and difficult processes lie ahead, but we need to be pro-active rather than reactive, both in enhancing cooperation where possible and in meeting the competition where necessary.

|

|

|||

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|