National Strategy for Pandemic Influenza Implementation Plan One Year Summary

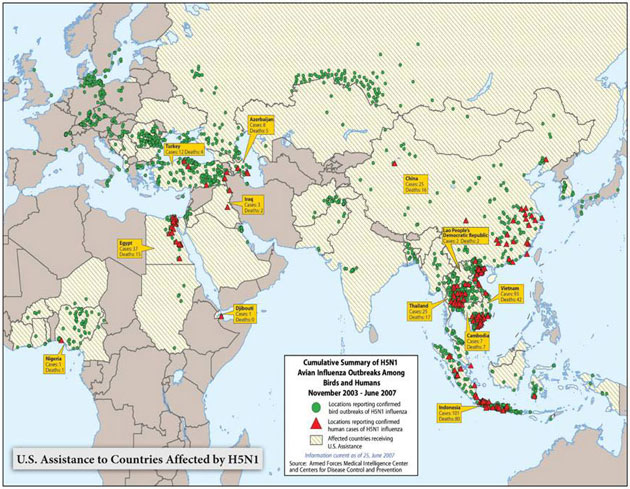

Limiting the International Spread of a Pandemic

At present, scientists believe that the likelihood of an avian virus changing into a virus that ultimately leads to the next influenza pandemic is greatest in places with widespread outbreaks in birds and with significant contact between infected animals and people. Reducing the opportunities for the virus to mutate, improving global disease monitoring, and helping other nations to prepare for and respond to outbreaks are key components of our risk mitigation strategy and a shared global responsibility. The United States has made pivotal contributions to control the international spread of H5N1 by working with affected countries and international partners to detect, contain, and prevent animal outbreaks, reduce human exposure to the virus, and enhance planning and preparedness for future outbreaks.

Leading the International Effort

In September 2005, President Bush announced the International Partnership on Avian and Pandemic Influenza (IPAPI) at the United Nations General Assembly. The Partnership was developed in concert with the World Health Organization (WHO) to align nations around a series of key goals including:elevating the issue of avian influenza on national agendas; coordinating efforts among donors and affected nations; mobilizing and leveraging resources; increasing transparency in disease reporting; improving surveillance; and building local capacity to identify, contain, and respond to an influenza pandemic. The challenge of avian influenza and the threat of a pandemic have required, and have produced, a coordinated international response, and the Partnership has mobilized the international community. The first meeting of the Partnership took place in Washington, DC in October 2005. In June 2006, 93 countries and 20 international organizations attended the IPAPI meeting in Vienna, Austria. Major international conferences have also taken place in Beijing, China in January 2006 and in Bamako, Mali in December 2006.

The United States is working on avian influenza issues in more than 100 countries, in collaboration with WHO, UNICEF, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE), and regional organizations, as well as with other international and in-country partners, including national governments and non-governmental organizations. The U.S. Government is supporting communications and public education activities in more than 50 countries to generate awareness about avian influenza and promote healthy behaviors and practices to reduce the risk of disease transmission. To help achieve this goal, the United States has supported the training of more than 113,000 people in the delivery of avian influenza communications messages.

U.S. Government agencies have deployed scientists, veterinarians, public health and communications experts, physicians, and emergency response teams to affected and high-risk countries to assist in the development and implementation of emergency preparedness plans and procedures for response to avian and pandemic influenza. As a result of these efforts, the United States and its global partners have made much progress across the spectrum of animal health protection, public health preparedness, information sharing, and public communication and awareness.

The United States Provides Assistance for Laboratories Overseas

The Lao People's Democratic Republic (Laos), a high-risk Southeast Asian country, has become a full participant in the Global Influenza Surveillance Network. The new Lao National Influenza Laboratory was established in 2006 with on-site U.S. Government assistance. In March 2007, the Lao laboratory identified a human case of H5N1 and sent the specimen to a WHO Collaborating Center for confirmatory testing. In 2006, the U.S. Naval Medical Research Unit in Egypt (NAMRU-3) assisted the Ukrainian Ministry of Health in establishing a national influenza laboratory that conducts molecular diagnostic testing for both seasonal and pandemic influenza. The United States provided equipment and reagents and provides ongoing confirmatory diagnostic testing. With technical and financial support from the United States, the Pacific Public Health Surveillance Network laboratory consortium in New Caledonia began routine testing of influenza viruses in 2006, and identified a new influenza A (H1N1) strain from the Solomon Islands that was recommended by WHO as a vaccine strain for vaccines to be used in the 2007-8 season. These examples represent major milestones in the development of capacity for pandemic influenza detection and response in priority countries.

Establishing Surveillance Capability Worldwide

Constant vigilance is the key to combating avian influenza and preventing pandemic influenza. By detecting avian influenza outbreaks early, with improved surveillance and laboratory diagnostic capacity, the world community has the opportunity to contain outbreaks in birds and intensify surveillance for human H5N1 cases that may accompany those outbreaks. When human cases occur, U.S. scientists are working with international partners to help determine whether the infecting virus is developing the capacity for efficient, sustained human-to-human transmission. The United States is supporting efforts to improve laboratory diagnosis and early warning networks in 75 countries and is working with its partners to expand on-the-ground surveillance capacity and improve knowledge about the movement and changes in H5N1 on a global scale. This includes support for improving national and regional laboratories to ensure that countries are able to quickly confirm the presence of H5N1 virus in people or animals so that a timely response is possible.

In 2004, the United States launched the Influenza Genome Sequencing Project to track genetic changes in viral strains. As a result, genome sequences of more than 2,250 human and avian influenza isolates have been made publicly available. Scientists around the world can now use the public sequence data to compare different strains of the virus, identify the genetic factors that determine their virulence, and develop new countermeasures. In 2006, the U.S. Government supported the creation of the Wild Bird Global Avian Influenza Network for Surveillance project in order to share information, increase the availability of scientific information for detection and containment, and track changes in virus isolates in wild birds.

The United States Helps Enhance Surveillance in High-Risk Areas

Due in large part to support from the United States, countries particularly vulnerable to avian influenza outbreaks have made significant developments in surveillance and response capacity at national and local levels. In Indonesia, an increasing number of high-risk areas are now able to provide weekly outbreak updates and launch outbreak response efforts within 24 hours. Contributing to this improvement are U.S. Government efforts to work with FAO and the Ministries of Agriculture and Health to develop participatory disease surveillance and response teams in all 154 avian influenza-endemic districts. The United States is also helping to expand local capacity for active surveillance across 27,000 villages in Java, Bali, and Sumatra through two Indonesian non-governmental organizations. In addition, increased surveillance and detection capacity in Laos allowed for rapid and accurate diagnosis of the July 2006 outbreak in poultry as an H5 avian influenza virus. These enhancements in surveillance resulted in more rapid response to outbreaks and improved containment to limit the spread of the virus.

The U.S. Department of Defense's Global Emerging Infections Surveillance and Response System (GEIS) supports surveillance activities in the military health system worldwide. Overseas, there are five laboratories located in Peru, Egypt, Kenya, Thailand, and Indonesia. These laboratories represent a global network of expertise in emerging infectious disease detection. The U.S. Navy's laboratory in Lima, Peru, expanded the number of sites from which it receives specimens from 12 sites in three countries to a total of 35 clinic/hospital sentinel sites in six countries of Central and South America, with plans for expansion to another four countries in 2007. The U.S. Naval Medical Research Unit in Cairo, Egypt (NAMRU-3) provides influenza surveillance including human and animal sampling in 19 countries in Africa, East Europe, the Middle East, and the former Soviet Union. Additional surveillance sites are being established in 2007 in six countries. Previously there was no consistent surveillance in sub-Saharan Africa. The U.S. Army Medical Research Unit (USAMRU) in Kenya now provides ongoing human influenza surveillance in the region. The U.S. Naval Medical Research Unit in Jakarta, Indonesia (NAMRU-2) has probably had the largest expansion in influenza surveillance efforts this past year because it is located in the epicenter of the H5N1 epidemic in the region. Syndromic surveillance has been expanded in 2006 to ten hospitals in the Lao People's Democratic Republic (Laos) and two in Cambodia.

Supporting a Coordinated International Response to H5N1 Avian (Bird) Influenza

Once an influenza virus with pandemic potential, such as highly pathogenic avian influenza A H5N1, is found in domestic birds, swine, or other domestic animals, it is necessary to eradicate the disease as quickly as possible and to take public health measures to minimize human exposure to the virus. If such a virus is found in wild birds or other wildlife, efforts should be directed at preventing it from being introduced into domestic birds or other susceptible animals.

The United States Helps Reduce H5N1 Outbreaks in Southeast Asia

Between 2003 and 2005, Thailand and Vietnam accounted for 88 percent of the world's H5N1 avian influenza outbreaks in animals. In 2005, there were at least 1,500 reported poultry outbreaks; however, the number fell to just 209 in 2006, and human cases fell from 75 to 3 over the same period of time. While many factors likely contributed to this shift, a substantial portion of this dramatic reduction in outbreaks can be attributed to the aggressive measures these countries, with U.S. Government support, have taken to combat avian influenza. As a result, countries across the region are more prepared and better able to mount effective outbreak response. In Cambodia and Laos, for instance, the time between onset of outbreaks and reporting has shortened from up to 5 weeks to 48 hours, significantly improving the opportunity for an effective outbreak response and containment.

The U.S. Government provided funding to strengthen WHO's Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN), which supports public health surveillance and response in nations worldwide. The United States, with international partners, is providing training for thousands of individuals who will lead efforts to detect, contain, and mitigate the impact of animal outbreaks and take steps to prevent future outbreaks from occurring. Over the past year, the U.S. Government has supported the training of more than 129,000 animal health workers and 17,000 human health workers in H5N1 surveillance and outbreak response. Since January 2006, the United States has deployed more than 300,000 personal protective equipment kits to over 70 countries for use by surveillance workers and outbreak-response teams. In cooperation with WHO and the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), U.S. experts have provided vital technical expertise to national investigations of actual outbreaks of H5N1 in countries on three continents and provided technical assistance, commodities, and logistical or financial support to 39 of the 60 countries and jurisdictions affected by H5N1 to date. As a result of the efforts of the United States and the support of our international partners, the international community is aware of outbreaks sooner and is able to launch more effective and timely responses.

The U.S. Government has expanded the HHS/CDC network of Global Disease Detection (GDD) Centers, which works closely with WHO-Geneva and WHO Regional and Country Offices. This program is a network of international centers of excellence dedicated to the surveillance of emerging infectious diseases, outbreak detection, identification, tracking, and response, as well as the provision of training programs for field epidemiology and laboratory scientists. New GDD Centers have been established in China, Egypt, and Guatemala, and GDD Centers in Thailand and Kenya have been strengthened. The GDD Centers in Thailand and Kenya have fully trained rapid response teams and stockpiles of protective equipment available for deployment internationally within 24 hours. Work is underway to establish regional rapid response teams and stockpiles at GDD Centers in China and Egypt.

Although the H5N1 avian influenza virus has not yet spread to North America, the United States is collaborating closely with Canada and Mexico through the Security and Prosperity Partnership to coordinate surveillance efforts for the early detection of the virus in wild birds migrating within and across North America. In the United States, a joint Federal/State program for the early detection of highly pathogenic avian influenza virus in wild birds has collected more than 145,000 samples from birds in all 50 States and territories since April 1, 2006. None of these U.S. samples tested positive for highly pathogenic avian influenza A H5N1.

The U.S. Government has completed acquisition of 140 million doses of avian vaccine. The National Veterinary Stockpile has entered into a contract for delivery of up to 500 million doses of an additional vaccine that can be used in young poultry. These avian vaccines can be acquired more rapidly than human vaccines because they, or similar vaccines, have already been tested and approved for use in poultry, in some cases long before highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 was a subtype of concern. Since May 2006, Federal veterinary specialists have participated in more than 50 State- and county-level exercises for highly contagious animal diseases, including avian influenza. The U.S. Government also held a national exercise that focused on the roles of Federal, State, and local government agencies, industry (primarily poultry), and consumer groups in collectively responding to an outbreak. More exercises are planned for 2007, with a focus on State- and tribal-level response planning and on mobilizing the National Veterinary Stockpile.

In addition, the U.S. Government has in place a process that provides real-time technical information and policy guidance to prevent the spread of avian influenza in commercial and other domestic birds and animals during a disease outbreak. This guidance includes biosecurity practices to help prevent disease from being introduced into a bird or flock, including restricting access to outside persons; preventing contact with wild birds; cleaning equipment, footwear, and vehicles; and separating new or returning birds from others in the flock for a period of time. Nearly one million copies of "Biosecurity for Birds" campaign materials have been distributed to all 50 States and more than 50 countries, and bilingual biosecurity information has been placed on more than 1.7 million poultry feed sacks. This guidance has also reached nearly 30 million readers through newspaper and magazine ads and 23 million listeners in 29 States through 30-second radio ads on national and regional agricultural radio networks.

International Response to Pandemic Influenza

By its very nature, a pandemic respects no borders. An outbreak of pandemic influenza anywhere poses a risk to populations everywhere. Our international effort to contain and mitigate the effects of an outbreak of pandemic influenza beyond our borders is a central component of our strategy.

The United States Responds to Human H5N1 Cluster

In May 2006, a cluster of human cases in Indonesia raised alarms that the disease may have spread between humans. Through prior preparedness planning and through coordination centered in the State Department with the U.S. Naval Medical Research Unit (NAMRU-2), the CDC, and the U.S. Agency for International Development, U.S. scientists, as part of a WHO team, were able to provide emergency support to the Indonesian Government. The international team investigated the outbreak, quickly analyzed samples through NAMRU-2 in Jakarta, and performed additional analyses and H5N1 confirmation through the CDC in Atlanta. This coordinated international response allowed WHO to quickly provide updates and reduce alarm as the cases were confirmed to be isolated incidents of inefficient human-to-human transmission and that the virus was not widely circulating among humans. The outbreak of avian influenza was not the start of a human pandemic, but the coordinated international response was an opportunity to practice what we intend to do if a pandemic arises.

The United States is working to enhance the ability of international organizations and individual countries to detect and respond to a pandemic. We are supporting many countries in their efforts to strengthen their laboratory diagnostic capacity, improve public communication, and develop national preparedness plans.

Although a pandemic virus has not yet emerged, the appearance of limited human clusters of H5N1 cases has tested our international surveillance and response capabilities. Since January 2006, U.S. Government scientists have assisted with on-site H5N1 investigations in Turkey, Nigeria, Romania, Djibouti, Indonesia, China, Laos, Vietnam, and southern Sudan. Investigative assistance included laboratory diagnosis, identification of disease risk factors, and analysis of clusters of disease to establish whether human-to-human (second generation) or human-to-human-to-human (third generation) transmission was occurring. U.S. Government scientists helped investigate several clusters of suspected human-to-human transmission including:a three-person family cluster in Thailand in 2004, in which limited second generation transmission was documented; three family clusters of H5N1 cases in South Sumatra, Indonesia, in 2005, in which the possibility of limited second generation H5N1 transmission could not be excluded for two of the clusters; and a large family cluster of H5N1 cases in North Sumatra, Indonesia (eight cases, seven deaths) in 2006, in which limited, non-sustained third generation transmission of H5N1 viruses likely occurred.

If, despite our efforts, a pandemic virus does emerge (i.e., the virus develops easy and ongoing transmission among humans), the United States and our global partners are preparing to mount an international rapid containment effort wherever the virus emerges in order to contain it or to slow its spread.

The United States has developed protocols and trained personnel to support an international effort to contain the pandemic in its earliest stages. The U.S. Government procured and pre-positioned overseas stockpiles of personal protective equipment, decontamination kits, and antiviral medications to complement global containment efforts.

National Border Measures: One Layer of Protection against the Pandemic Virus

If a pandemic begins outside the United States, and international containment efforts fail, the U.S. Government has planned a series of layered border measures that may be implemented incrementally during a severe pandemic to slow the entry of a pandemic virus into the United States while allowing the flow of goods and people. These border measures during the early stages of a severe pandemic may include flight restrictions from affected regions, issuance of health guidance to travelers intending to enter the United States, health screening of travelers before departure, en route, and on arrival to the United States, as well as public health measures to limit onward transmission of the disease.

We are working closely with our neighbors Canada and Mexico to establish a common North American approach to delay the arrival and impact of a pandemic. One of the objectives of the pandemic planning efforts in the Security and Prosperity Partnership is the development of the North American Plan for Avian and Pandemic Influenza. This trilateral plan, now being finalized, establishes a framework for coordinated, trilateral actions regarding communication, responses to avian and pandemic influenza, border monitoring, and critical infrastructure protection. Developed as part of the Plan is a concept of operations for responding to aircraft inbound to North America that are carrying passengers potentially infected with the pandemic virus. This approach is currently being shared with other aviation partners around the world. U.S. Quarantine Stations, located at ports of entry and land-border crossings where international travelers arrive, will play an important role in delaying the introduction of pandemic influenza into the United States and helping to limit its spread. The number of quarantine stations in the United States has more than doubled since 2004, expanding from 8 to 20 locations, with quarantine stations in Dallas and Philadelphia added this past year.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|